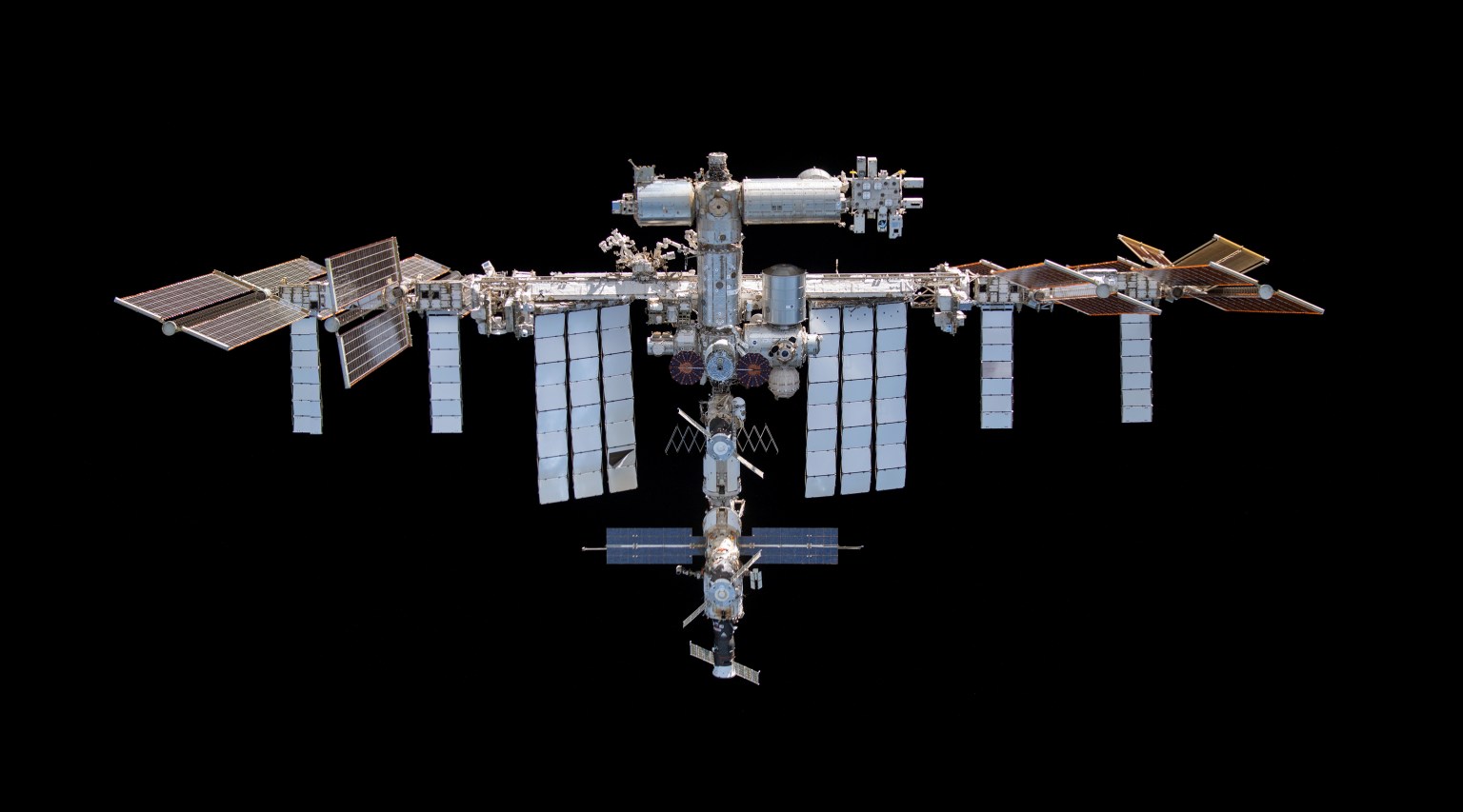

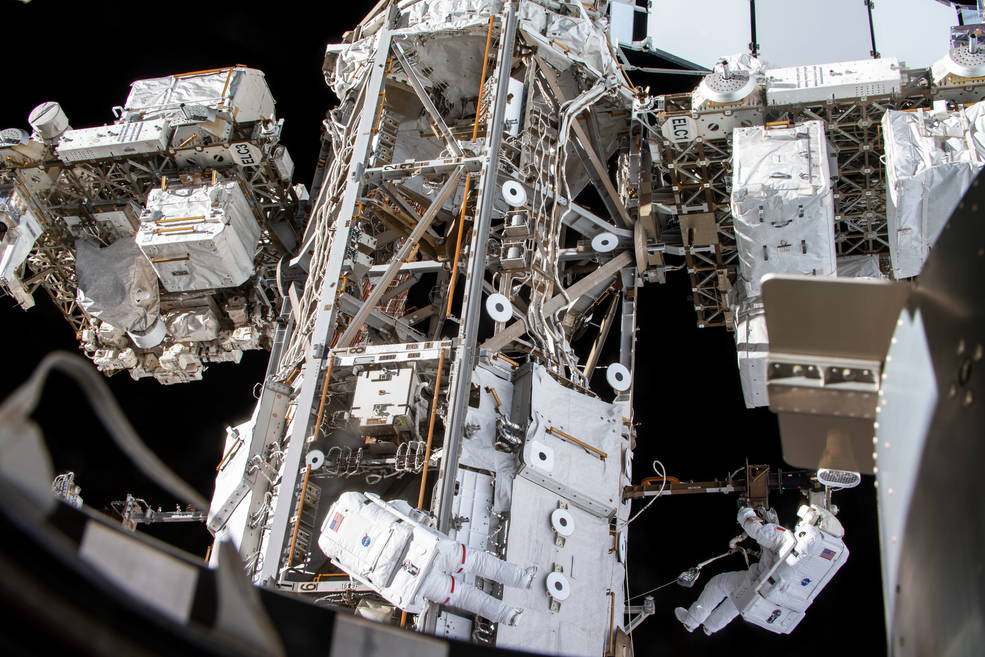

Assembly of the International Space Station (ISS) would not have been possible without the skilled work of dozens of astronauts and cosmonauts performing intricate tasks in bulky spacesuits in the harsh environment of space. Spacewalks, or extravehicular activities (EVAs), were indispensable to the assembly of ISS and today remain important to the continued maintenance of the world class laboratory in low Earth orbit.

Left: Leonov during the world’s first EVA in March 1965. Right: White during the first American EVA in June 1965.

On June 3, 1965, astronaut Edward H. White opened the hatch to the Gemini 4 capsule and, as he floated out of the cabin, became the first American to walk in space. A few weeks earlier, on March 18, Soviet cosmonaut Aleksei A. Leonov took the world’s first spacewalk as he floated out of an airlock attached to his Voskhod 2 spacecraft. Although White’s 36-minute EVA appeared effortless, later spacewalkers in the Gemini Program found accomplishing actual work quite challenging. Because NASA considered mastering spacewalking a critical task for the Apollo Moon landing program, astronauts and engineers expended much effort to learn the required skills, and by the final flight of the Gemini program astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin proved that EVAs could be productive. His training in an underwater environment to simulate spacewalking proved to be a game-changer and the practice has been standard ever since.

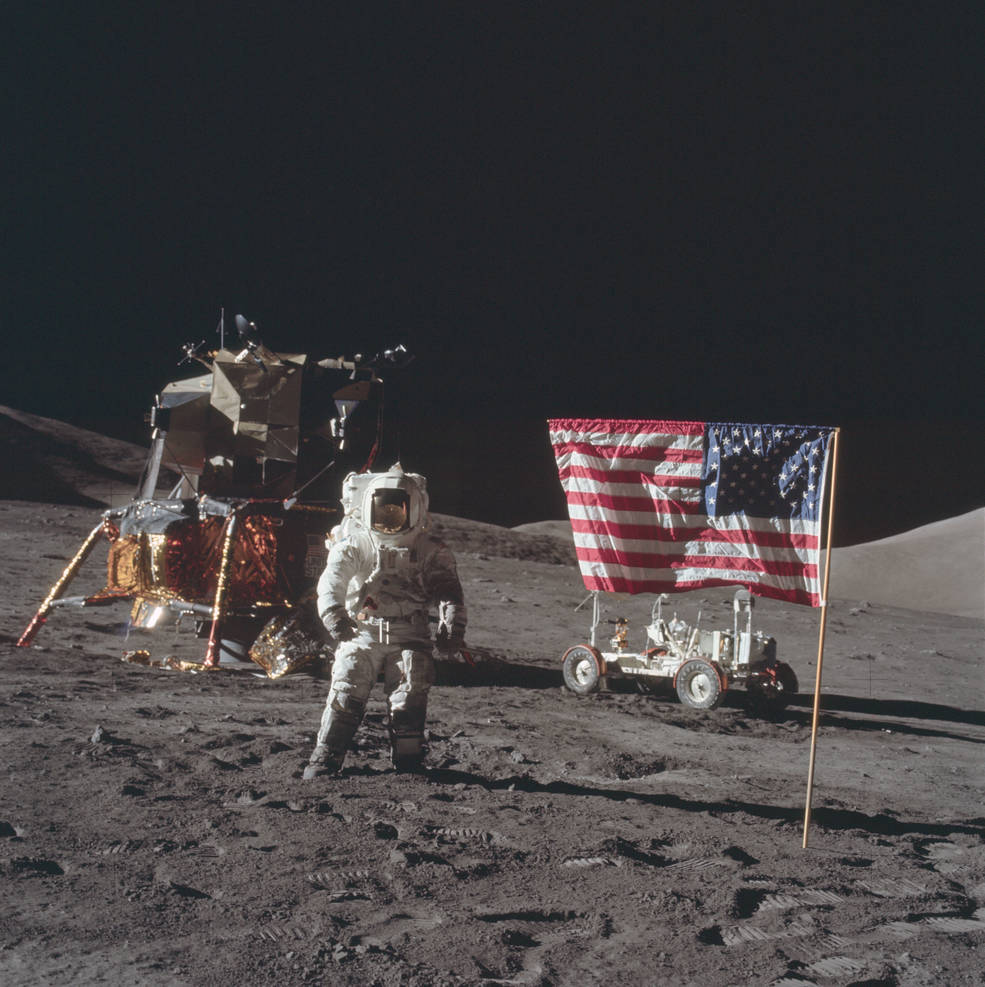

Left: Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt during an EVA on the lunar surface in 1972. Middle: Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson during the final EVA of the Skylab Program in 1974. Right: Soviet cosmonaut Georgi M. Grechko preparing for the first EVA aboard the Salyut-6 space station in 1977.

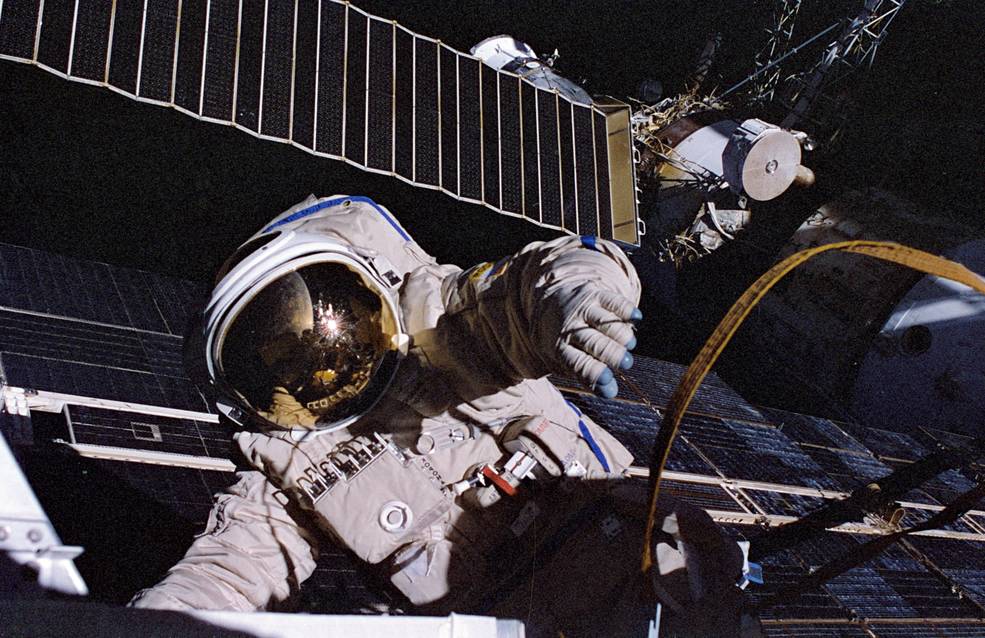

Most spacewalks during the Apollo Program took place on the lunar surface and extended EVA durations past seven hours through upgrades to the spacesuits or Extravehicular Mobility Units (EMUs). Spacewalks conducted aboard Skylab in the mid-1970s proved the value of spacesuited astronauts to carry out repairs and maintenance of the space station – indeed, the EVA to free Skylab’s jammed solar array played a key role in saving the program. Similarly, beginning in the late 1970s, Soviet then Russian cosmonauts using ever-improved Orlan spacesuits proved the value of EVAs in inspecting, maintaining, repairing and augmenting space stations.

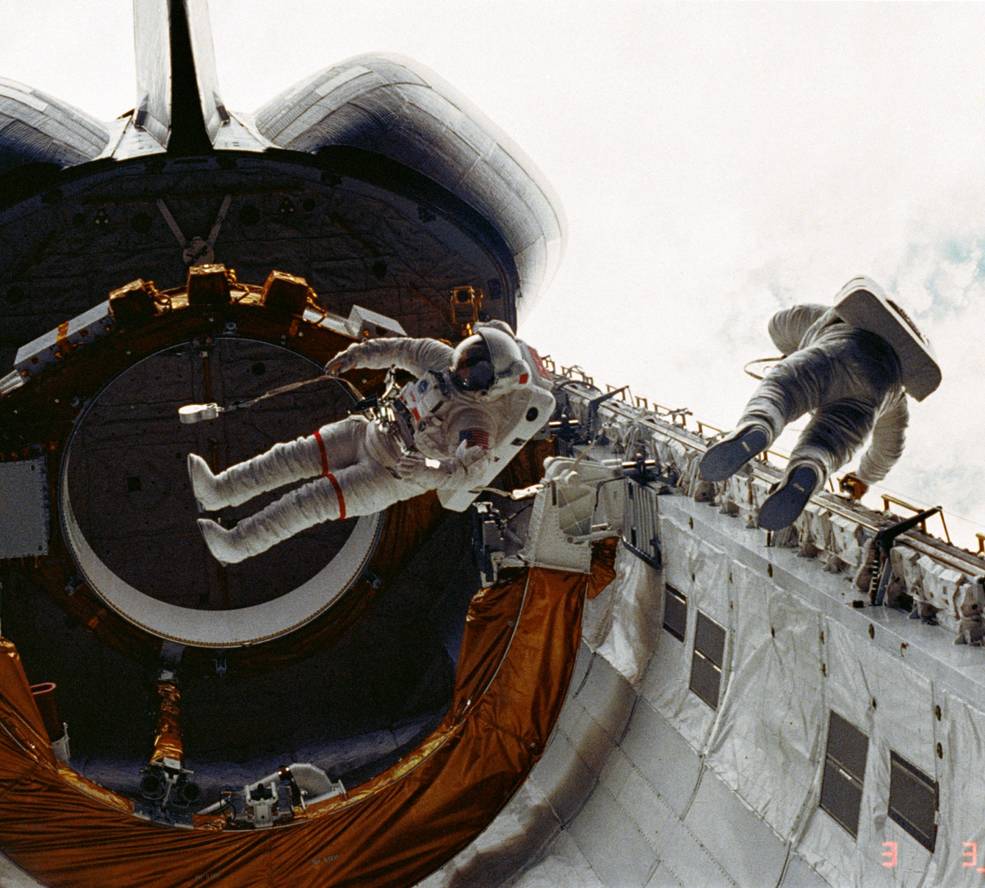

Left: STS-6 astronauts F. Story Musgrave (left) and Donald H. Peterson during the first Shuttle EVA in 1983. Middle: Mir 20 crewmembers Sergei V. Avdeyev (left) and European Space Agency astronaut Thomas A. Reiter in 1995. Right: STS-125 astronauts John M. Grunsfeld and Andrew J. Feustel preparing to reenter the Shuttle’s airlock after the final Hubble servicing EVA in 2009.

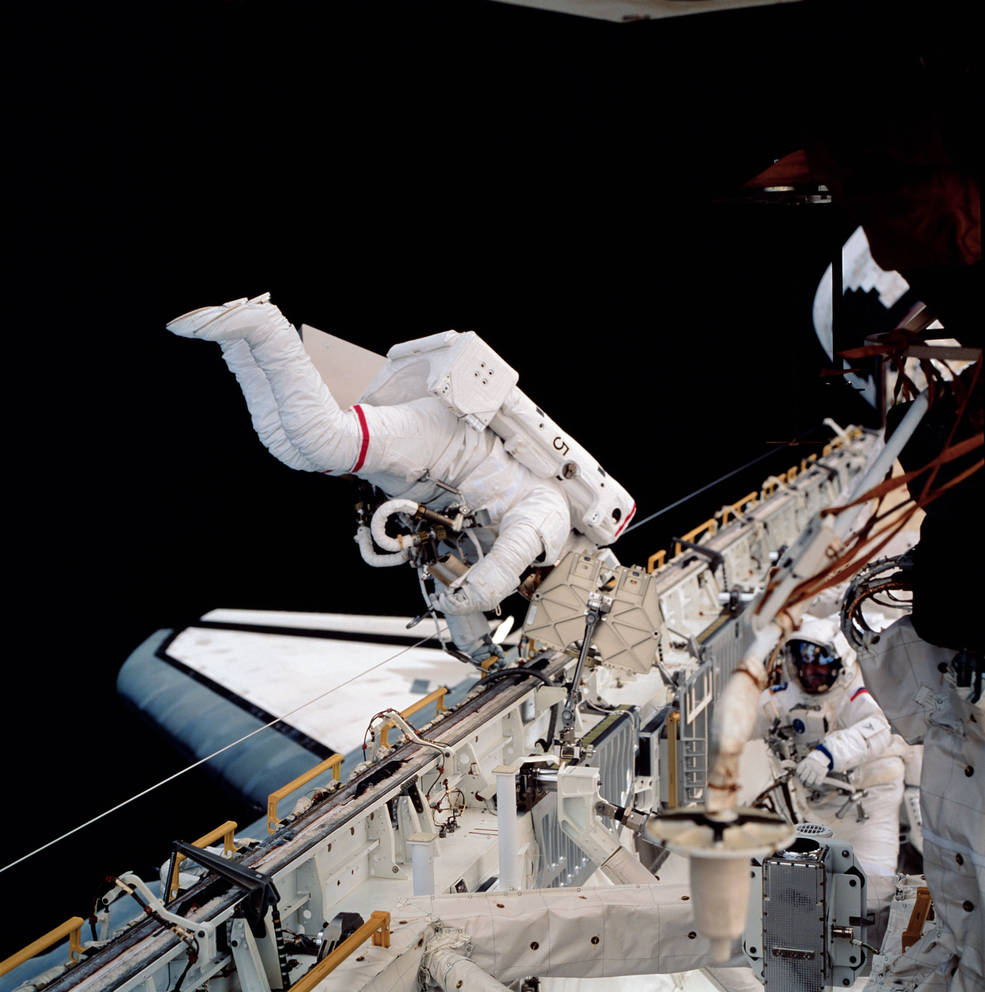

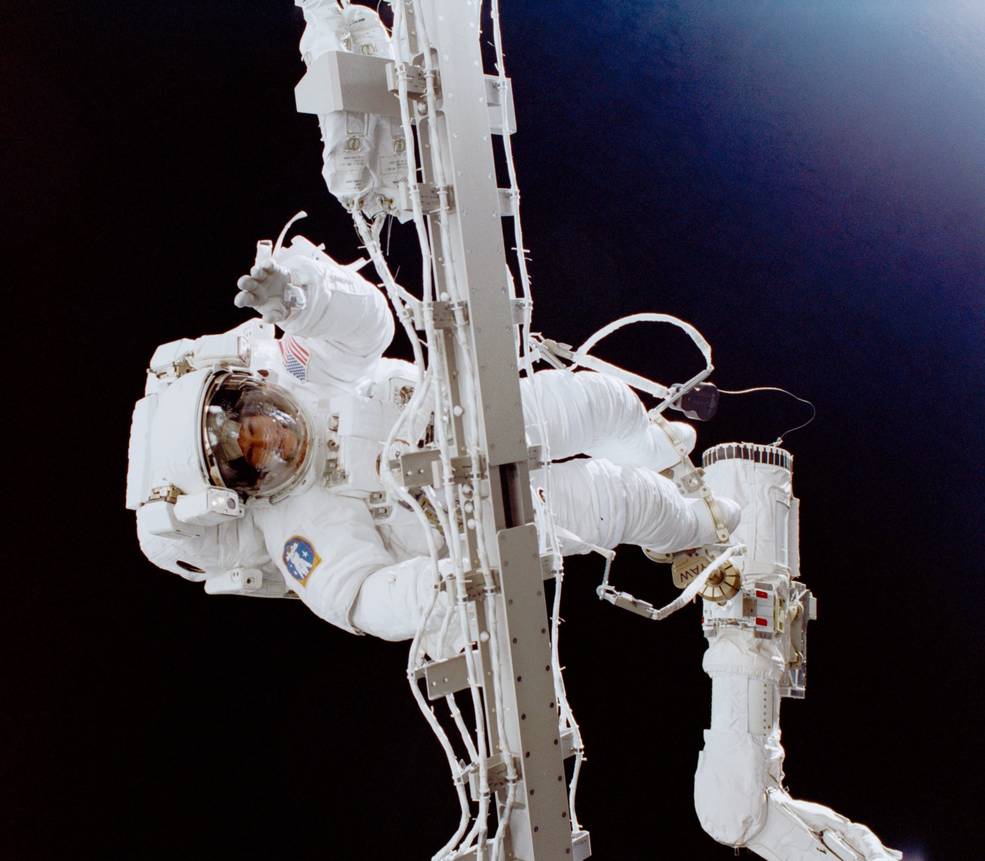

Spacewalks during the Space Shuttle era demonstrated that astronauts during EVAs could capture, repair and redeploy satellites, test future refueling of spacecraft and evaluate assembly techniques. From the first EVA during STS-6 in 1983 to the last non-space station related Shuttle EVA during STS-125, the final Hubble Servicing Mission in 2009, astronauts completed 52 spacewalks, 23 of them dedicated to servicing the Hubble Space Telescope in the course of five missions. Cosmonauts aboard the Mir space station made extensive use of EVAs for construction, maintenance and scientific and technology research during 79 spacewalks over the facility’s 15-year orbital lifetime. Mir also hosted the first EVA by a non-Russian crewmember, Jean-Loup Chrétien from France in 1988.

Left: Linenger during his EVA with Tsibliev outside Mir. Right: Parazynski (left) and Titov during the STS-86 EVA at Mir.

One of the stated objectives of the Shuttle-Mir Program, also known as Phase 1 of ISS, was for the United States and Russia to learn to work together as the two former adversaries prepared to jointly build and operate the space station. One arena where this was clearly demonstrated was in spacewalking. As Phase 1 progressed, astronauts living and working aboard Mir became more involved in the station’s operations, including conducting EVAs. On April 29, 1997, Jerry M. Linenger became the first American astronaut to perform an EVA in a Russian Orlan spacesuit with his Mir 23 commander Vasili V. Tsibliev. C. Michael Foale and David A. Wolfe added to that experience base with their Mir Orlan EVAs later that year. Foale became the first person to perform EVAs in both the US EMU and the Russian Orlan spacesuits. On Oct. 1, 1997, Scott E. Parazynski and Vladimir G. Titov performed the first joint US-Russian EMU EVA during STS-86 while Space Shuttle Atlantis was docked to Mir. Titov was also the first non-American to conduct a Shuttle-based EVA.

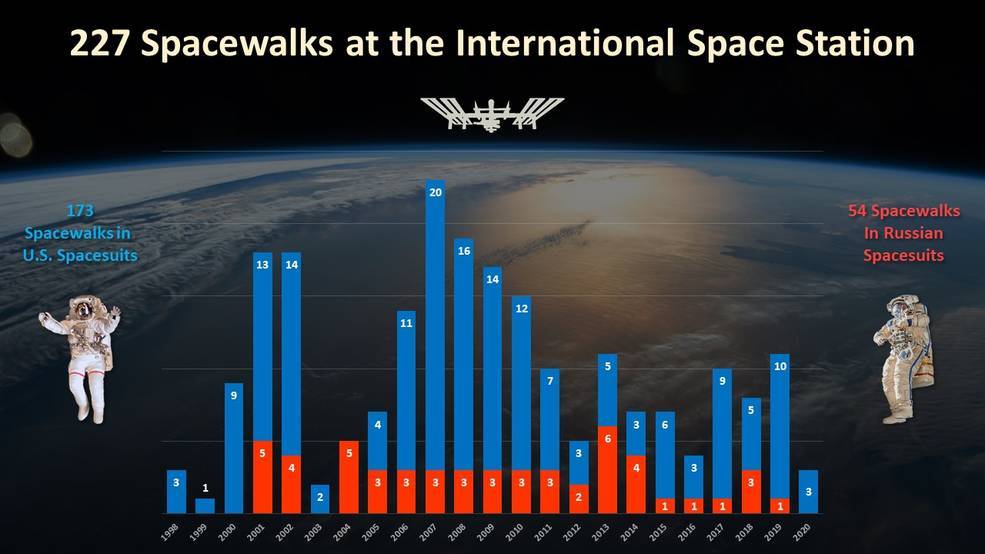

Graphic representation of the number of ISS EVAs over the past 22 years.

The complex assembly of ISS would have been impossible without the skilled labors of spacewalking astronauts and cosmonauts. The cumulative experience of the EVAs conducted in the years prior to the start of ISS assembly formed a solid basis on which to build the necessary spacewalking skills. It is of interest to note that 23 years passed between Leonov’s first daring venture into open space and the first EVA at ISS, during which time 171 spacewalks were completed in low Earth orbit, on the Moon and in deep space. In the 22 years since the first ISS assembly EVA, 227 spacewalks dedicated to ISS have been accomplished plus an additional 13 during Space Shuttle missions unrelated to ISS, 4 on the Russian Mir space station and 1 by the People’s Republic of China.

Left: STS-88 astronauts Newman (left) and Ross perform the very first EVA at ISS in 1988. Middle: STS-96 astronaut Jernigan moving the Strela Grapple Fixture adaptor. Right: STS-106 crewmembers Malenchenko (left) and Lu connect cables between Zarya and Zvezda during the first joint US-Russian EVA on ISS.

From the very first assembly mission, spacewalks proved to be essential to preparing the fledgling ISS for its first occupants. Astronauts Jerry L. Ross and James H. Newman conducted the first ISS EVA on Dec. 7, 1988, during the STS-88 mission to connect electrical and data cables between the station’s first two modules, Zarya and Unity. Over the course of the first five Shuttle assembly missions, 12 crewmembers conducted 10 EVAs prior to the Expedition 1 crew taking up residency aboard the station. During STS-96, the second assembly mission in May 1999, Tamara E. “Tammy” Jernigan became the first of many women to perform an EVA at ISS. Astronaut Edward T. “Ed” Lu and cosmonaut Yuri I. Malenchenko conducted the first US-Russian EVA at ISS during the June 2000 STS-101 mission. The two connected electrical and data cables between Zarya and the newly-arrived Zvezda module. Training for that spacewalk required Russian engineers to modify the Hydrolab facility at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center to accommodate the US EMUs. Similarly, American engineers adapted the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at Johnson Space Center to allow the Expedition 1 crew to train using both the EMU and the Russian Orlan spacesuit.

Left: Expedition 2 astronaut Helms during the longest EVA to date. Middle: STS-100 astronaut Hadfield, the first Canadian to perform an EVA at ISS. Right: Expedition 2 crewmembers Voss (left) and Usachev in the hatchway to Zvezda’s Transfer Compartment preparing for the first Russian Segment EVA.

Following the arrival of Expedition 1 crewmembers William M. Shepherd, Yuri P. Gidzenko and Sergei K. Krikalev aboard ISS on Nov. 2, 2000, the pace of assembly and the number of spacewalks increased significantly. Between December 2000 and April 2003, 38 astronauts and cosmonauts completed 41 EVAs, including the first staged from ISS itself rather than from the Space Shuttle. On March 10, 2001, Expedition 2 astronauts James S. Voss and Susan J. Helms conducted a spacewalk during STS-102 that at 8 hours and 56 minutes still stands as the longest EVA in history. In April 2001, Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris A. Hadfield became the first Canadian to conduct an EVA at ISS during STS-100, the flight that brought the Canadarm2 robotics system to the space station. On June 8, Voss joined Expedition 2 cosmonaut Yuri V. Usachev for the first Russian segment EVA, an internal spacewalk in Zvezda’s Transfer Compartment to prepare it for the arrival of a new module.

Left: STS-104 astronauts Gernhardt emerging to begin the first EVA from the ISS Quest Joint Airlock. Middle: Expedition 3 cosmonauts Dezhurov (left) and Tyurin about to begin the first EVA from the Pirs module. Right: STS-111 crewmember Perrin, the first French astronaut to perform an EVA at ISS.

The STS-104 mission in July 2001 brought the Quest Joint Airlock to the station, providing ISS with a standalone EVA capability, with accommodations for both the US EMU and the Russian Orlan suits. Michael L. Gernhardt and James F. Reilly performed the first EVA from Quest on July 20. The Pirs module arrived at ISS on Sept. 17, providing the Russian segment with a true airlock capability. On Oct. 8, Expedition 3 cosmonauts Vladimir N. Dezhurov and Mikhail V. Tyurin staged the first EVA from Pirs. Along with American and Russian crewmembers, international partners continued to play a role in spacewalking, with Philippe Perrin becoming the first astronaut from France to perform an EVA at ISS during the STS-111 mission in June 2002.

Left: Expedition 8 Commander Foale preparing for the first “two-person” EVA. Middle: STS-114 astronaut Noguchi performing the first EVA for JAXA at ISS. Right: Expedition 13 astronaut Reiter conducting the first EVA by an ESA crewmember at ISS.

Following the Space Shuttle Columbia accident, ISS EVAs continued but only from the Russian segment with the added complication that with the resident crew size reduced to two, the pair of spacewalking crewmembers left no one inside the station to monitor its systems. Although this posed a slightly increased risk should something go wrong, these “two-person” EVAs proved essential during the Shuttle hiatus. Expedition 8 crewmembers Aleksandr Y. Kaleri and Mike Foale conducted the first such EVA on Feb. 26, 2004. Foale had prior experience with the Orlan suit as he had completed an EVA during his long-duration stay aboard Mir in 1997. The crew had to cut the EVA short due to Kaleri’s suit overheating and water droplets forming inside his helmet. The crew later identified the problem as a kink in the water line in his liquid cooling garment. The incident provided a preview of a more serious problem to occur in an EMU during an EVA more than nine years later. On the STS-114 Shuttle Return-to-Flight mission, Soichi Noguchi became the first astronaut from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency to conduct an EVA at ISS on July 30, 2005. The first European Space Agency astronaut to perform an ISS spacewalk was Expedition 13 crewmember Thomas A. Reiter from Germany, on Aug. 3, 2006.

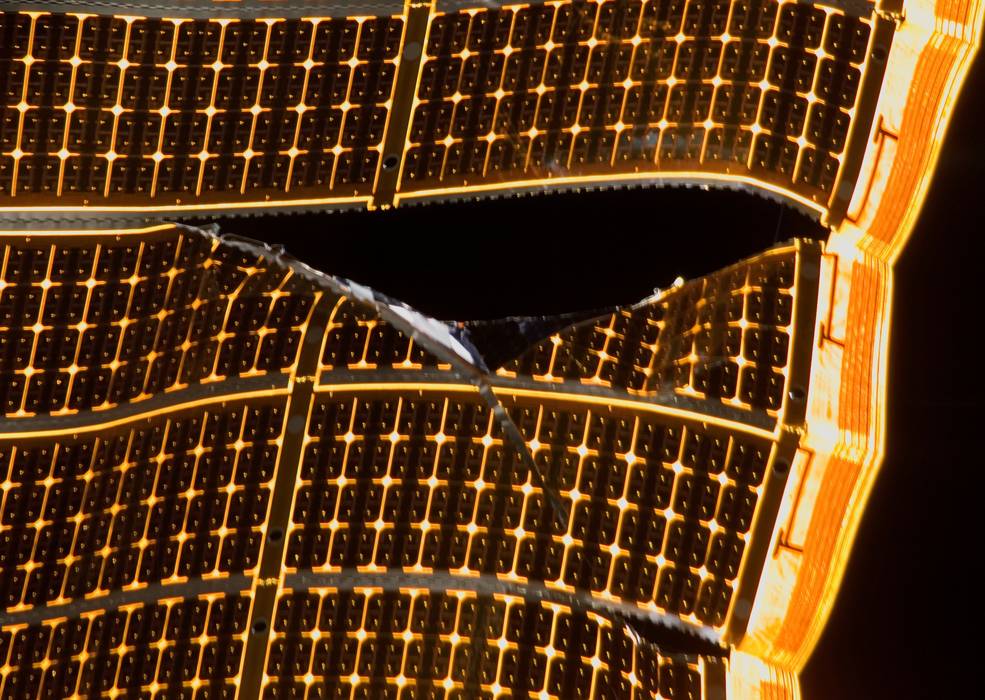

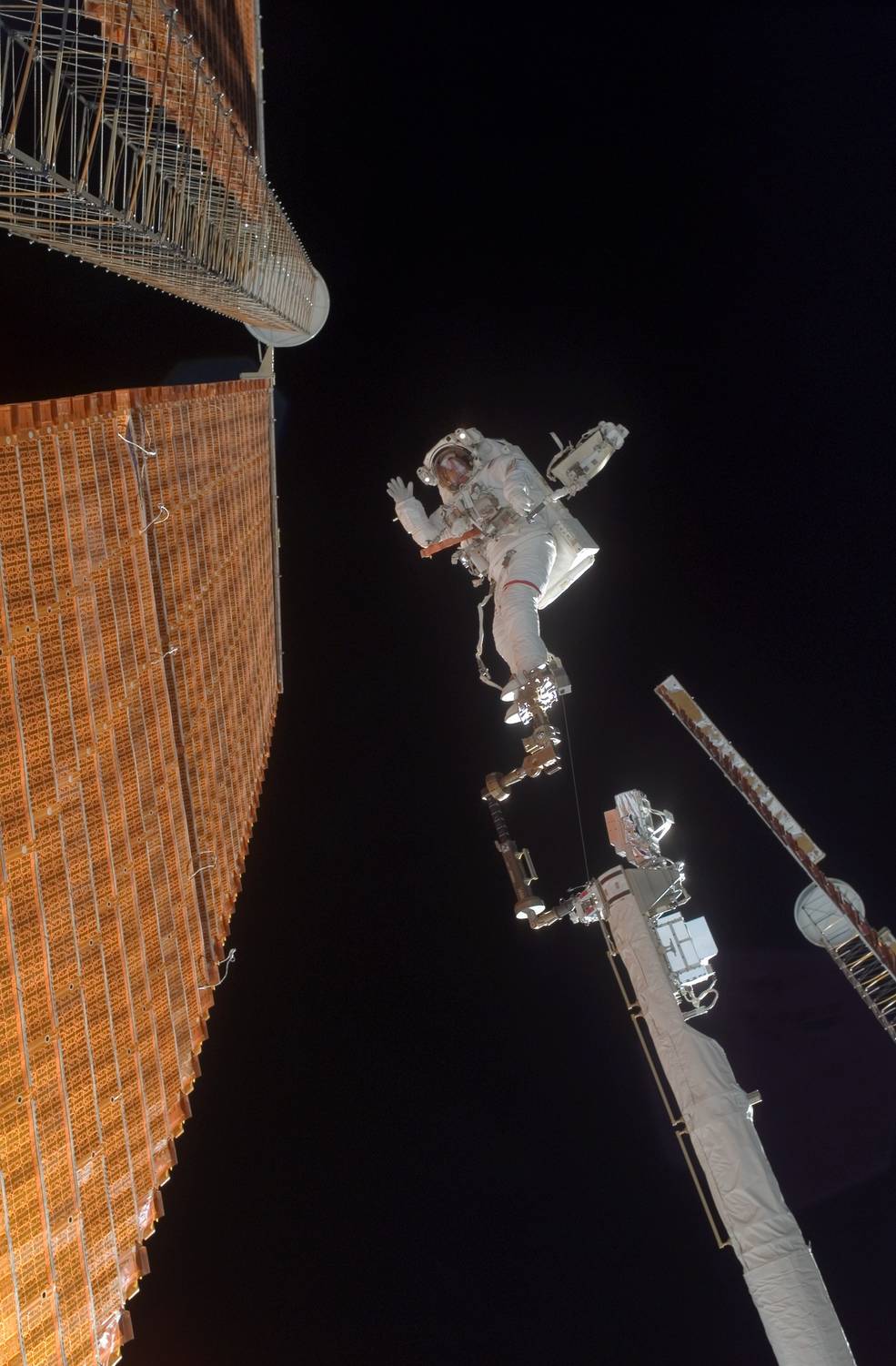

Left: Closeup of the tear in the solar array. Middle: STS-120 astronaut Parazynski atop the robotic arm and boom near the site of the tear. Right: Parazynski approaches the tear to effect the repair.

Although all spacewalks carry a certain amount of risk, two examples illustrate how some EVAs are riskier than others. The objectives of the STS-120 mission in October 2007 included not only delivery of the Harmony module to ISS but also the relocation of the P6 truss segment from its location atop the Z1 truss, where it had been since December 2000, to the outboard port side truss. During the overall reconfiguration of the station’s power systems earlier in 2007, the P6’s solar arrays were rolled up. After the crewmembers relocated P6 to the outboard truss, they began to unfurl the two arrays. The first array opened without incident, but with the second array nearly unfurled the astronauts noticed a tear in a small portion of the panel and immediately halted the deployment to prevent damaging it. Working with the onboard crew, mission managers devised a plan to have one of the astronauts essentially suture the tear in the panel. Appropriately enough, one of the two STS-120 spacewalkers, Scott E. Parazynski, was also a physician and he put his suturing skills to good use. Attached to a portable foot restraint, Parazynski was hoisted atop not only the station’s robotic arm but also the Shuttle’s boom normally used to inspect the Orbiter’s tiles, the impromptu arrangement providing just enough reach for Parazynski to successfully repair the torn array using a newly-designed tool dubbed “cufflinks.” After he secured five cufflinks to the damaged panel, crewmembers inside the station fully extended the array as Parazynski monitored the event.

Left: Expedition 36 astronaut Parmitano during EVA23. Right: Expedition 36 crewmembers Nyberg (left) and Yurchikhin assist Parmitano with removing his EMU after his safe return to the airlock.

Luca S. Parmitano, the first astronaut representing the Italian Space Agency to conduct an EVA at ISS, and his fellow Expedition 36 crewmember Christopher J. Cassidy began US EVA23, their second EVA together, on July 16, 2013, without incident. Forty-four minutes into the EVA, as the two crewmembers worked on their individual tasks at different locations on ISS, Parmitano reported feeling water at the back of his head. Mission Control advised them to halt their activities as they devised a plan of action. Cassidy came to Parmitano’s side to assess the situation, at first believing that a leaking drink bag inside the suit was the source of the water. But as Parmitano indicated that the amount of water was increasing, Mission Control advised them to terminate the EVA, directing Parmitano to head back to the airlock and Cassidy to clean up any tools and then follow his crewmate back to the airlock. As Parmitano began translating back toward the airlock, the water continued to increase, migrating from the back of his head, filling his ears so he had difficulty hearing communications and eventually obscuring his vision and interfering with breathing. He made his way back to the airlock mostly by memory and feel, and after Cassidy joined him inside they repressurized the module. Expedition 36 crewmates Karen L. Nyberg and Fyodor N. Yurchikhin helped Parmitano quickly remove his helmet and towel off the estimated 1 to 1.5 liters of water. Later investigation indicated that contamination on a filter caused blockage in the suit’s water separator. Although Parmitano faced a potentially life-threatening situation, his calm response along with quick decisions by the team in Mission Control resolved the crisis successfully. He later joked during an in-flight press conference that he “experience what it was like to be a goldfish in a fishbowl from the point of view of the goldfish.”

Left: Preparing for the first all-woman EVA are Expedition 61 astronauts Meir (left) and Koch. Right: The latest EVA on ISS in January 2020, performed by Expedition 61 astronauts Morgan (left) and Parmitano.

The Expedition 61 crew completed a record nine EVAs between Oct. 6, 2019, and Jan. 25, 2020. Five involved tasks to replace batteries on the P6 truss segment and three to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), a physics experiment not originally designed for on-orbit repairs. Of note, Christina Koch and Jessica U. Meir conducted the third battery-replacement EVA on Oct. 18, the first time all-female spacewalk in history. The pair completed two more EVAs in January 2020. Their fellow crewmembers, Andrew J. “Drew” Morgan and Luca Parmitano, completed the most recent EVA to date, the final spacewalk to repair AMS.