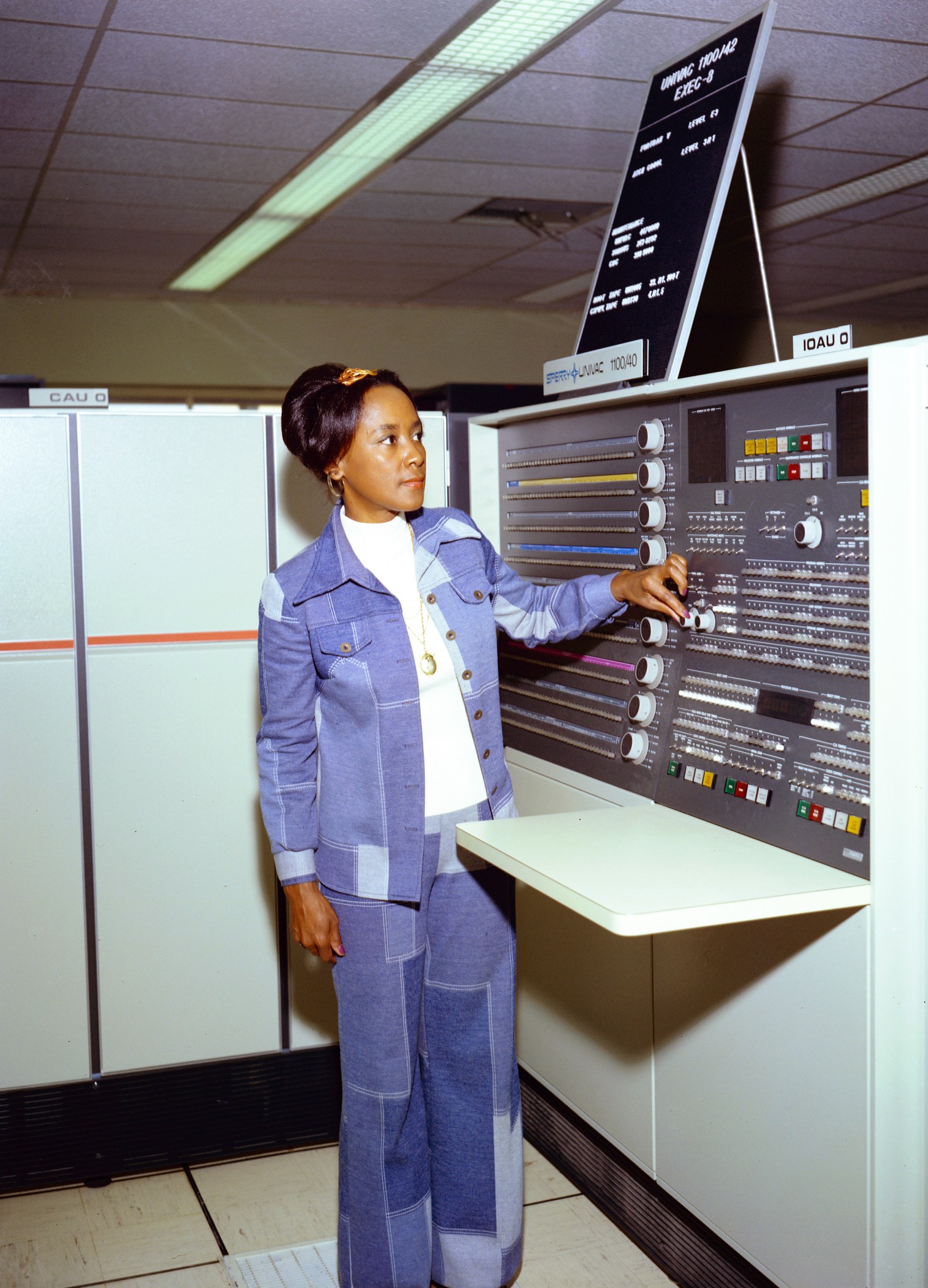

Excerpt from an interview with Annie Easley, by Sandra Johnson

Cleveland, Ohio

21 August 2001

Johnson: When you first came to Cleveland, you decided that school at that point was out of the question because it was too far away, and you said you just heard about the NACA, and read about it.

Easley: I read about it. There was an article in the local paper.

Johnson: And decided it sounded like an interesting job. Did you have any expectations about that job already, other than what was in the article, or when they interviewed you or told you about the job, when you actually started work, were you surprised at what you were doing? I guess, like we were talking about before we started, how no one really knows that NASA or NACA was here, it was all—

Easley: Well, I didn’t know that it was here until I read the—I’d never heard of it until I read the article, but it was such an article that the things that were described, the work that was being done by those sisters, those twin sisters, those computers, the people called computers, it was very interesting to me. It was something that I had a real interest in doing, and I was not disappointed when I came out, when I had the interview, and when I started to work. I just thoroughly enjoyed it and I enjoyed my career here at NASA, at NACA, and to see it become what we were, and the many changes that were made. But no, the job as I saw it, the work, as I encountered, there were no disappointments, ever.

Johnson: You were a computer?

Easley: I was a computer at first.

Johnson: Can you describe what your job was when you first started?

Easley: When I first started, going back many, many years, I started here in 1955. I started with NACA in 1955. Our jobs were really to do the computations for the engineering side of the house. The engineers and the scientists are working away in their labs and their test cells, and they come up with problems that need mathematical computation. At that time, they would bring that portion to the computers, and our equipment then were the huge calculators, where you’d put in some numbers and it would clonk, clonk, clonk out some answers, and you would record them by hand. Could add, subtract, multiply, and divide. That was pretty much what those big machines, those big desktop machines, could do.

If we needed to find a logarithm or an exponential, we then pulled out the tables and did it. We’d look up the tables and then put it in by hand. Or a square root. All those things, we had tables that we looked up. And that’s why, in my lifetime, to have seen where we were and where we are, that I can have a little tiny something the size of, oh, gosh, well, my watch, practically, and it can give me all of those functions that used to take up so much space and so much time to do. And the clonk, clonk, clonk, clonk.

But I went through—that was the beginning. This is all doing the computations. But after that, I remember when it was such a big step when we got the computers themselves. The thing with the key-punched cards, where we’d go in and punch the cards. All of our instructions on a set of cards, a deck of cards, we called them. And then we’d travel to some other building where the computers were, and feed those cards into a machine and they would print out some answers internally, and a new set of cards would be punched out, with our answers on that new set of cards. And then we’d physically take those cards over to another machine that would print out the answers on great big huge sheets. That was a process that we did time and time again. But we had progressed from doing those things by hand.

So I’ve just watched these series of generations of computers and I just find it fascinating that it’s like historical, where we are today. We can just do things instantly now with the equipment that’s available. That was kind of the beginning of working at NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. I have to try and recall it. It was fun.

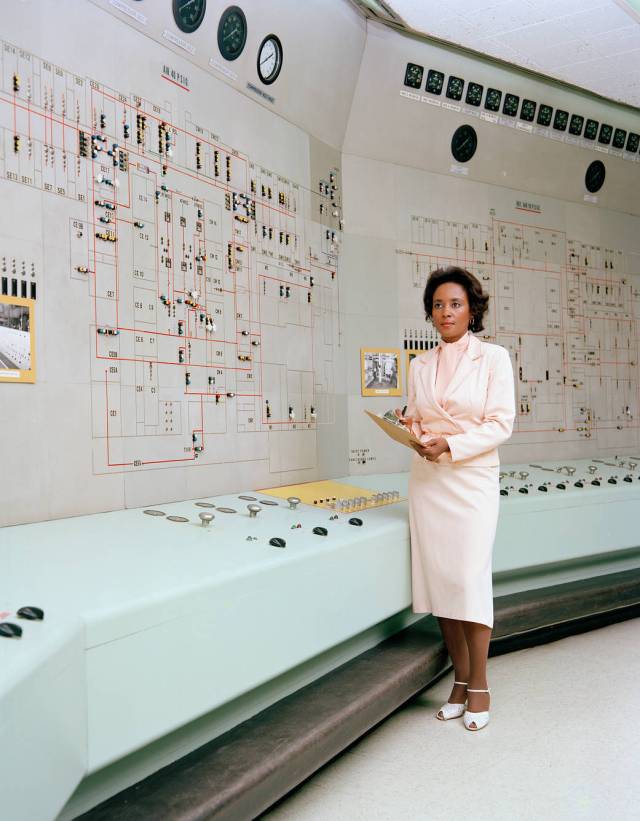

Annie J. Easley

From human computer to computer scientist, learn about Annie Easley's career at what is now Glenn Research Center.

Read her biography

Johnson: During the sixties, like we were talking about, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, do you feel that that affected your position or your work here anyway, either one of those things?

Easley: I think it was more, they insulated themselves. I think there were still the die-hards who didn’t see that there were problems that needed to be solved. I think there were people who felt, “This is the way it always was and it’s doing fine.” As you said, you’ve talked to people who said they were not aware of what was going on, and that may very well be true of some people. It’s like, it’s someone else’s problem, it’s not ours. And it’s only when we started to—we, the employees, had to get to management and talk and talk and talk and talk, to tell them, “Look, there are problems. There’s not equality. If there was equality, we would not need an EEO [Equal Employment Opportunity] office. We would not need any of that. We would not need any laws that say, this is what you need to do to bring things in compliance.” So it has not been all peaches and cream. We do need those laws.

I was an EEO counselor at one time, and just talking to some of the supervisors, their mindset was just closed. I’m sure you know what a counselor does, the EEO counselors within NASA. It was not just—a lot of people thought it was minorities and women, but as soon as they added the age category, a lot of the complainers were white males over forty who felt they were being discriminated against.

So it’s a kind of thing, discrimination of any kind can affect a lot of different people, and sometimes those people don’t realize it until later on, they’re affected. Then they can begin to look back and say, “Oh, that’s how someone felt,” because now they’re on the other end. They may have been right up on top and they find themselves in a position of, boy, they took away all of my authority. I really don’t have anything interesting to do. So it affects a lot of us, but at different times. It may take some people longer to learn than others.

Johnson: In the late sixties and after the last moon shot and in the beginning of the seventies, there were a lot of budget cutbacks in NASA, and I believe Lewis experienced quite a few cutbacks.

There were quite a few people laid off during that time. How did that affect the work that you were doing or the people that you worked with? Were people in your group affected?

Easley: Well, the whole entire lab, as we called our place, the lab, we were all affected in some ways, but there was an uncertainty because there was not a real pattern as to what would be cut and who would go. I think it was 1970, is the first time reality set in that, yes, the government does fire people. You can call it RIF, reduction in force, but the bottom line is, they went out. And there was a bit of uncertainty the day that—you hear rumors. There were things in the paper that there are going to be some cutbacks. I think some of us grew up believing that civil service jobs were forever, and secure. We didn’t think of them as ever letting people go, and that’s just the way our mindsets were. We’d been told that or we chose to believe that, so when there were the cuts, it was a bit unsettling.

I think we took it—yes, the group I was in, there were some people who were let go, but we never figured out the pattern. But the way it was done, the division chief, a personnel rep, were in the building, in the division chief’s office and the division secretary would call a person down to the office, and that is how they were told they were let go.

We found out, we sort of got wind of it and we started to, I guess we used a little levity by saying, “Let’s not answer the telephone if the phone rings.” Because we had one phone per office. If there were six people in the office, we all shared one inside line, and we just didn’t know at the end of the day, you still—and to this day, I think a lot of us still don’t know how people were chosen to be let go. And we went through that at least twice, or three times, where there was this massive layoff. It was not a pleasant thing, because you don’t know—you’re sitting there wondering, okay, who’s going to get the next phone call. And it was not necessarily the last one hired, the first one fired.

In another group, I remember a young man who had just finished—he was working while going to school and he had just finished college, and had earned a scholarship someplace. But the division chief called him into his office and said, “Congratulations. Read this.” And it was the proverbial pink slip. And I remember this young man saying he was the rudest person he’d ever seen, to do that in the way he did it. And he said he thought he was not the last one [hired]. Theoretically, the way they thought it would be done was the less seniority would go first, but that wasn’t true in that case. When I talk about the way people did things, this is an example of someone saying, “Well, I knew that you were going to leave anyway. That’s why you were chosen to be let go.” They don’t know that he was really going to go. He’d earned the scholarship, but there’s nothing that said he was going to go. There were no guarantees, or that was not a way to do it.

So yes, people were affected, all over. Some more than others, like emotionally. It’s a big upheaval when your life is turned around like that, and so, yes, a lot of people. That was a very sad time. It was very, very sad. And then you sort of settled in. Some people were let go, some people were put in other jobs. We actually had one of the engineers, life scientist, out here, was let go of his job, but he had a right to take a typing test, and he did. He became a typist. He became a cleric for a while. He passed the test. I don’t know the rules, but a lot of people were affected and it’s not pleasant. And you didn’t walk around saying, “Oh, gosh, I was saved.” You wondered, “Well, why? And why was that person let go?”

So it was not pleasant. Those were bad times. And of course, we got rid of one whole division. The Nuclear Division was eliminated. And that was a lot of people. At the time, I think most of the operations out of our Plum Brook facility were shut down. Because remember, I said back in the late fifties, early sixties, we had this big surge, and now it was not by attrition. It was like, you go now. So that was bad. It was sad times.

Want more? Read the whole transcript.