Apollo 16 entered lunar orbit on April 19, 1972. The next day, NASA astronauts John W. Young and Charles M. Duke separated their Lunar Module (LM) Orion from Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly, who remained in orbit aboard the Command Module (CM) Casper. After a delay caused by a problem with the Service Module’s main engine, Young and Duke touched down at the Descartes site in the lunar highlands. They conducted three surface excursions totaling more than 20 hours, using a Lunar Roving Vehicle for transportation. They deployed an experiment package, collected 209 pounds of rock and soil samples, and set up the first telescope on the Moon. In the meantime, Mattingly conducted observations and photography of the lunar surface from orbit. After their 71-hour lunar surface stay, Young and Duke prepared to rejoin Mattingly in orbit.

Left: Image of the Sea of Moscow on the lunar farside. Middle: Earthrise during Apollo

16’s second revolution around the Moon. Right: Saenger Crater on the lunar farside.

Following the April 16, 1972 launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Apollo 16’s translunar coast lasted 74 hours. During the astronauts’ fourth day in space, their spacecraft’s trajectory took them past the leading edge of the Moon, and as they disappeared behind it. As expected, all contact with the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, temporarily stopped. Thirty minutes later, the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine fired for 6 minutes, 14 seconds for the Lunar Orbital Insertion (LOI) burn to drop them into an elliptical 196-by-67-mile lunar orbit. Young became the first person to orbit the Moon on two separate missions, his first being Apollo 10 in May 1969. As they reappeared from behind the Moon, he radioed to MCC, “Hello, Houston. Sweet 16 has arrived!” Of the LOI burn, Young reported, “That baby just rifled it right down the line.” From the MCC, Donald H. Peterson, capsule communicator (capcom) on Flight Director Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin’s Gold Team of controllers, replied, “All righty.” Young, Mattingly, and Duke all described the scenes of the lunar terrain as it passed by beneath them. Peterson reported to the crew that the Saturn V rocket’s spent third stage impacted on the Moon, detected by the three seismometers left on the surface by the Apollo 12, 14, and 15 crews.

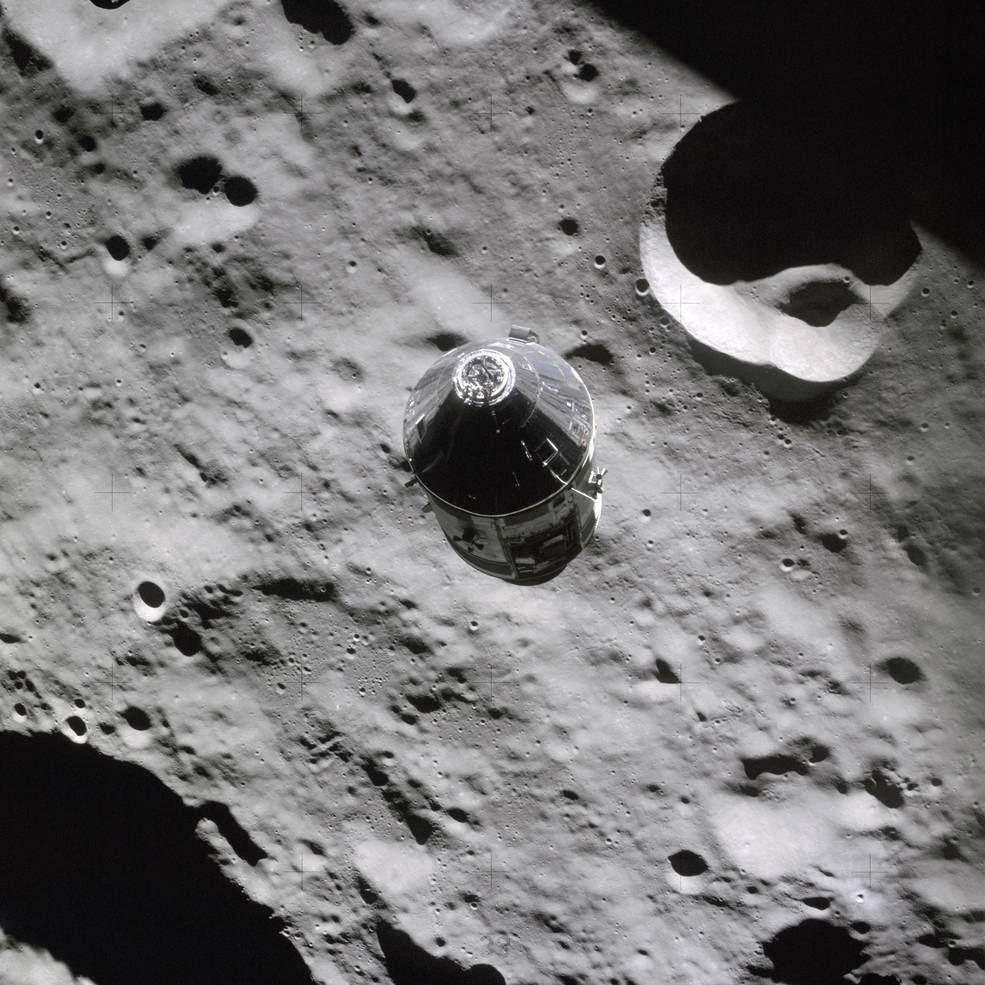

Left: The Apollo 16 Command Module Casper shortly after undocking in lunar orbit.

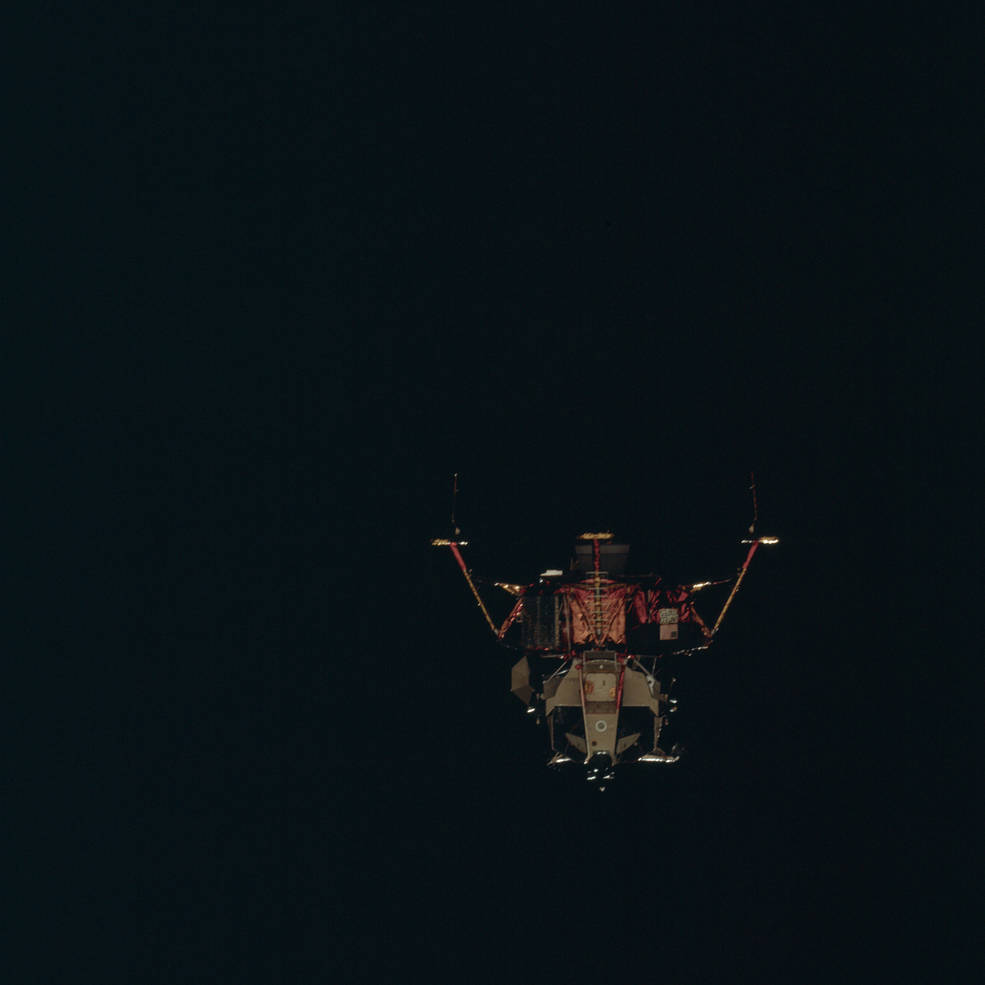

Middle: The Apollo 16 Lunar Module Orion shortly after undocking in lunar orbit.

Right: Senior managers huddle in Mission Control to resolve the problem with

Apollo 16’s Service Propulsion System engine.

After Apollo 16 went behind the Moon at the end of the first revolution, Flight Director M.P. “Pete” Frank and his Orange Team of controllers, including capcom Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield, took over the consoles in MCC. At the end of the second revolution, and once again behind the Moon, the astronauts performed the Descent Orbit Insertion maneuver. The 24-second burn using the SPS engine changed their orbit to 68-by-12 miles above the surface, prompting Duke to comment that it looked like they were “clipping the tops of the trees.” Mattingly began to activate the experiments in the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay in the Service Module. As Apollo 16 passed behind the Moon on its fourth revolution, the astronauts began a nine-hour sleep period. While they slept, in MCC, Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz leading his White Team of controllers, including Peterson as capcom, assumed their console positions. The astronauts awoke to begin their fifth day in space during their ninth revolution around the Moon. In MCC, Flight Director Griffin resumed his position for the undocking and landing, with James B. Irwin now serving as capcom for Young and Duke in the LM Orion and Edgar D. Mitchell for Mattingly in the CM Casper. The astronauts donned their spacesuits, and Young and Duke floated into the LM and powered its systems up. While behind the Moon on their 12th revolution, the two spacecraft undocked and the astronauts inspected each other’s spacecraft. After passing behind the Moon at the end of the 12th revolution, as Mattingly prepared to fire the SPS engine to circularize his orbit to 60 by 78 miles, he encountered a serious problem, reporting to Young and Duke, “I be a sorry bird.” An oscillation in the secondary control system for the SPS engine caused the entire spacecraft to shake. Mattingly postponed the maneuver and Young and Duke in Orion prepared to redock, should that prove necessary. When they rounded to the front side of the Moon, they described the problem to MCC, where a team of engineers immediately began working on a solution while the landing remained in doubt. Without a working SPS, the astronauts would have to rely on the LM’s descent engine to fire them out of lunar orbit. Mission Control had five revolutions, about 10 hours, to develop a solution before Apollo 16’s orbital track took it too far west to allow a landing at Descartes. During the 15th revolution, Mission Control informed the astronauts that they were “go” for the landing on the following orbit, the oscillations in the backup control system not serious enough of a problem to cancel the landing.

Left: The Command Module (CM) Casper and the rising Earth as seen from the Lunar Module (LM) Orion. Middle: The LM seen at a distance from the CM. Right: View of the lunar surface from a LM window during the descent.

At the beginning of the 16th revolution on the backside of the Moon, Mattingly completed the delayed circularization burn, placing Casper in a 61-by-78-mile orbit. Shortly after the start of the frontside pass and six hours later than planned, Young and Duke fired Orion’s descent engine to begin the Powered Descent Initiation burn to drop them from lunar orbit. For the first 26 seconds of the burn, the engine ran at 10% thrust, then increased to 93%. At 7,200 feet, the LM pitched over to near vertical, allowing Young and Duke to see their landing site up ahead, with all the familiar landmarks they had seen in the training simulators. At about 300 feet, Young took over manual control of the descent since the spacecraft’s computer was steering them toward a shallow 45-foot-wide crater. The LM’s engine began kicking up lunar dust at about 80 feet, partially obscuring their view of the landing site. Young hovered for a few seconds, then eased Orion down until landing probes on three of the LM’s footpads made contact. He cut the engine and Orion fell the final three feet. Apollo 16 had arrived at Descartes.

Left: The first image taken on the surface at the Descartes landing site from astronaut John W. Young’s window. Middle: View of the Apollo 16 landing site shortly after touchdown. Right: View from astronaut Charles M. Duke’s window.

Shortly after touchdown, Young looked out the window and reported to Houston, “Well, we don’t have to walk far to pick up rocks, Houston. We’re among them!” Duke added enthusiastically, “Old Orion is finally here, Houston. Fantastic!” Because the landing occurred six hours later than planned, Young and Duke, with MCC’s concurrence, decided to sleep before starting their first lunar surface excursion. They removed their spacesuits, strung up their hammocks, and slept for several hours. In Mission Control, Griffin’s team, with Anthony W. “Tony” England serving as the capcom, took their consoles. Since England would serve as capcom during the Moonwalks, Peterson took his place while the crew slept.

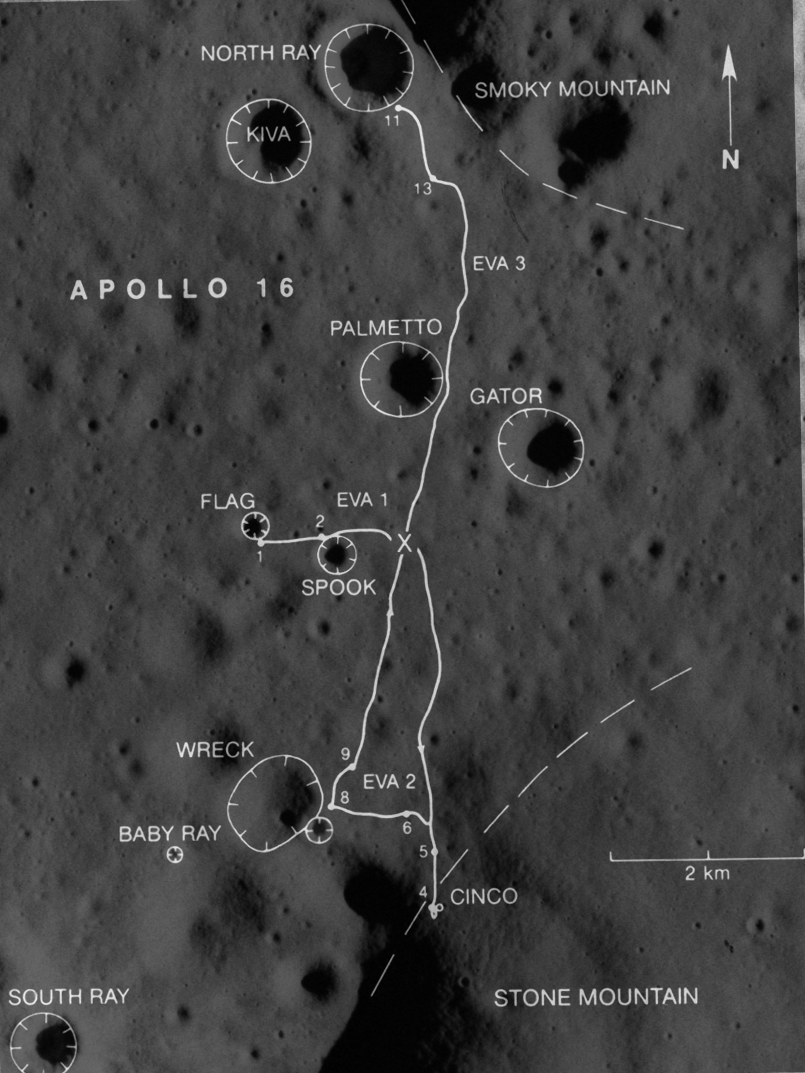

Map of the Apollo 16 landing site and the routes of the three traverses.

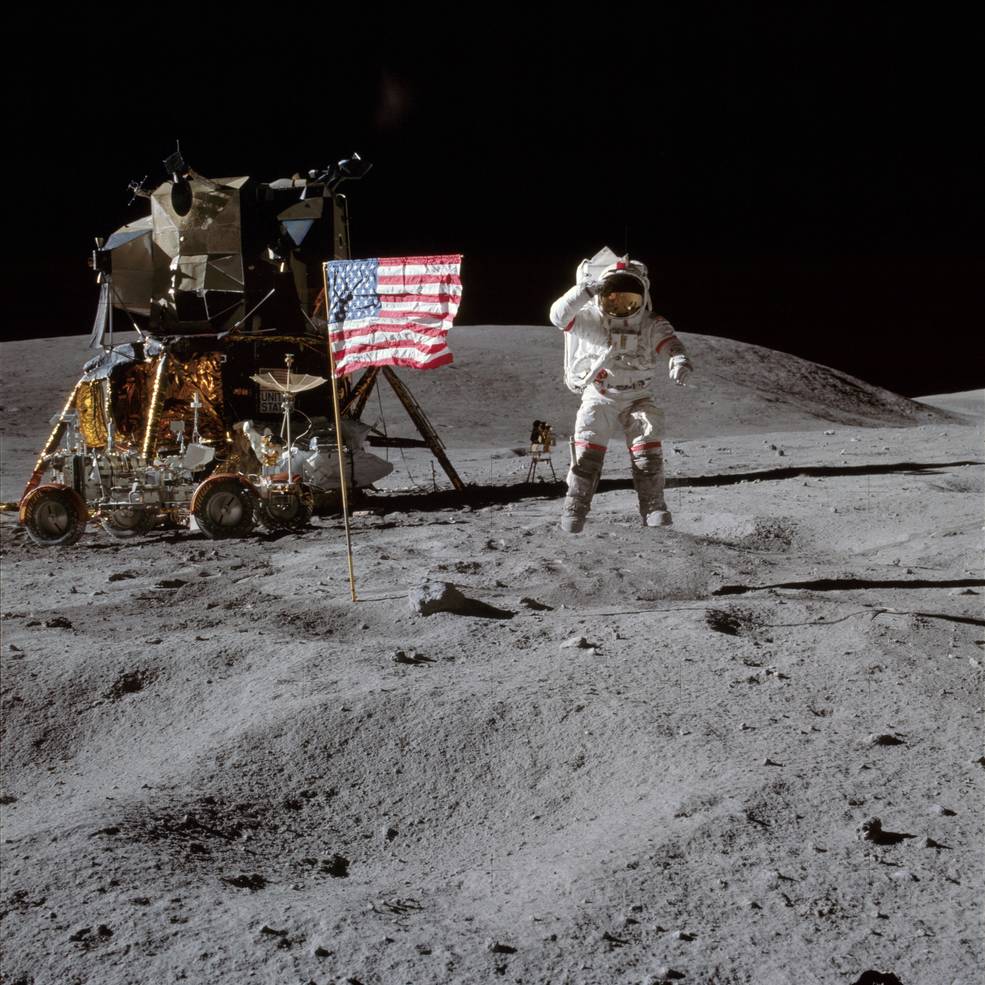

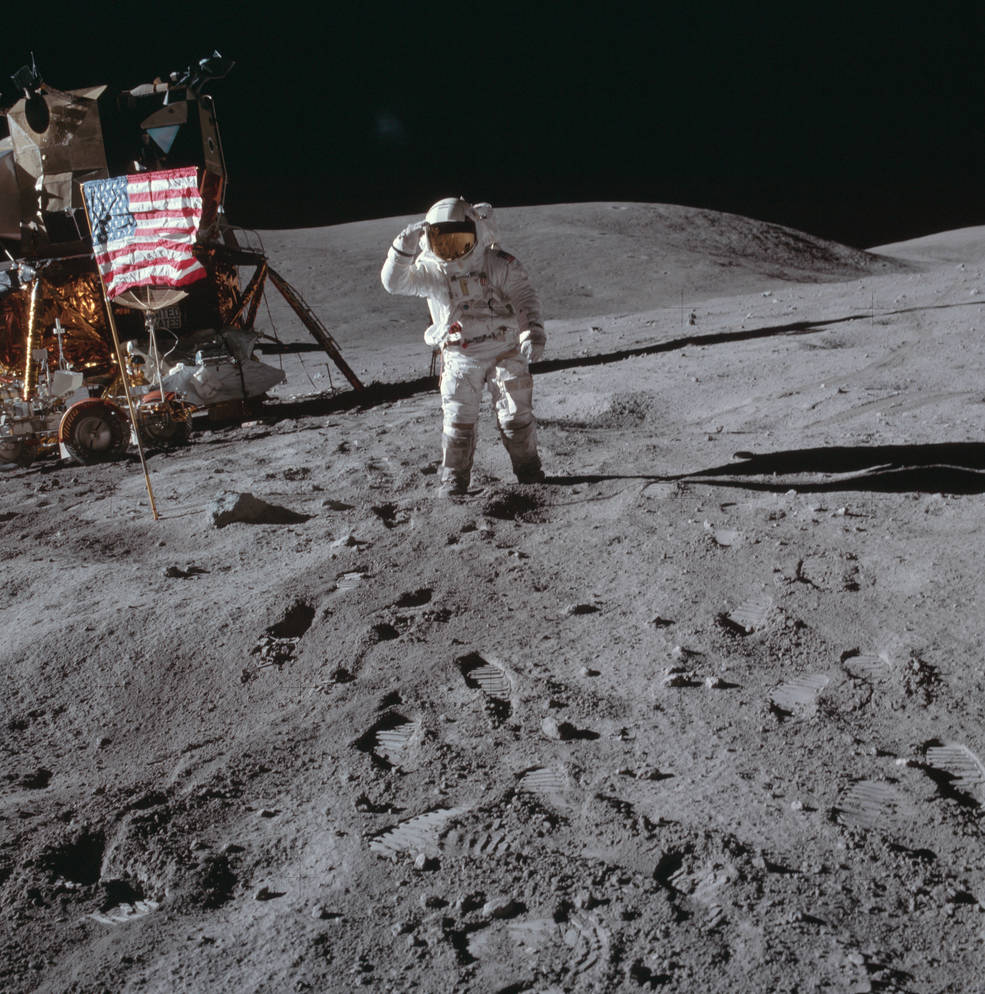

On the morning of the sixth mission day, Young and Duke awoke and began preparations for their first lunar excursion. They donned their spacesuits and depressurized the LM. Young exited first through the side hatch, climbed down the ladder, and stepped onto the lunar surface, saying, “There you are: Mysterious and Unknown Descartes. Highland plains. Apollo 16 is gonna change your image.” Duke followed two minutes later, telling capcom England, “Fantastic! Oh, that first foot on the lunar surface is super.” One of their first tasks involved deploying the Lunar Roving Vehicle, or Rover, which they accomplished with very few problems. On his first test drive, Young noted that the rear steering didn’t work, but the problem later cleared up on its own. Duke took the first set of panoramic photos, including of the 45-foot-wide crater just a few feet behind the LM toward which the computer had been steering them. Young retrieved the far ultraviolet (UV) camera/spectrograph from its stowage compartment and set it up in the LM’s shadow. From this vantage point, the camera took unprecedented images of the Earth and other objects in the UV spectrum. Duke installed the high-gain antenna and the TV camera on the Rover. From MCC, Edward I. “Ed” Fendell operated the camera remotely to monitor the astronauts’ activities. Young removed the American flag from its stowage location and planted it in the lunar soil next to a large rock. He and Duke took turns photographing each other with the flag, with Young leaping in the air while saluting. Capcom England informed them that the U.S. House of Representatives passed NASA’s budget including funding for the proposed space shuttle, prompting Young to respond, “The country needs that Shuttle mighty bad. You’ll see.”

Left: View of the crater directly behind the Lunar Module (LM) Orion that astronaut

John W. Young overflew during the approach and landing. Middle: Young gives a

leaping salute to the American flag. Right: Astronaut Charles M. Duke

salutes the American flag.

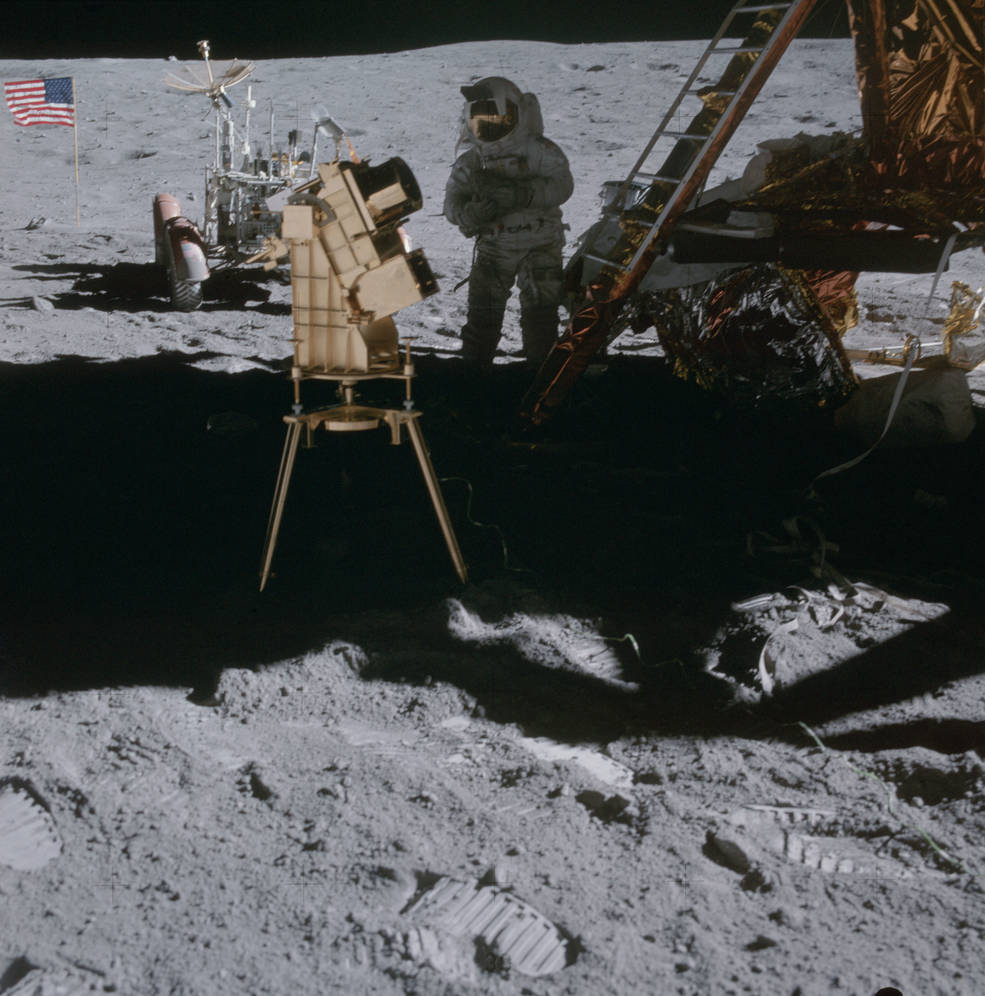

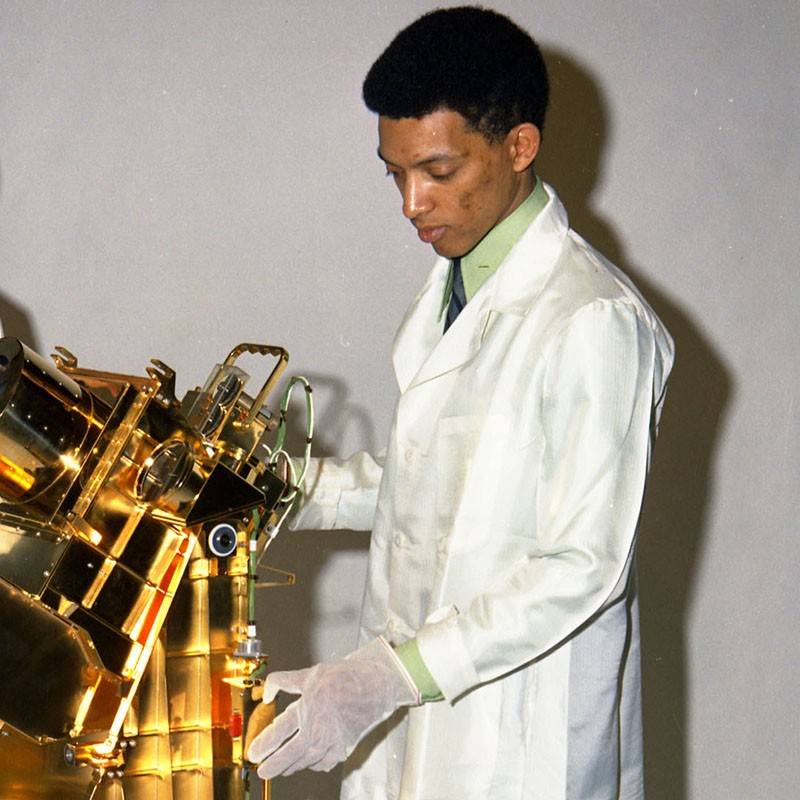

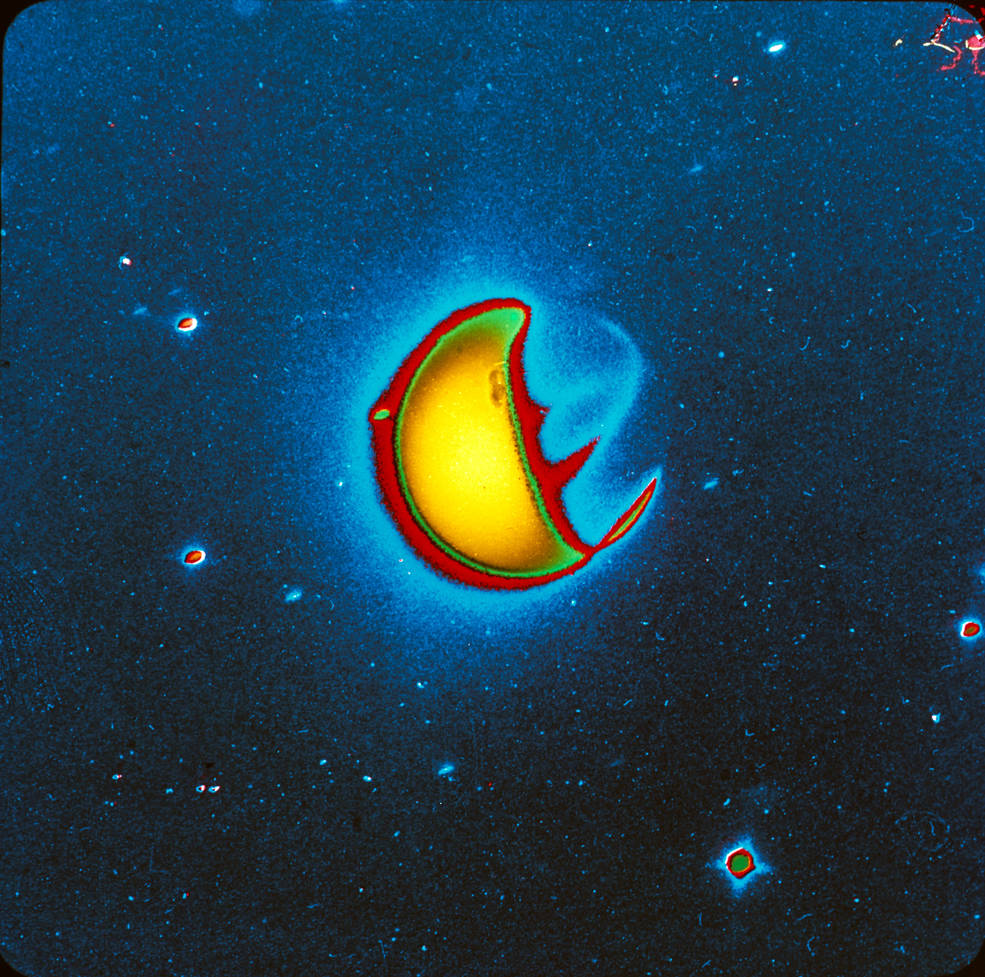

Left: The far ultraviolet camera/spectrograph set up in the shadow of the Lunar Module

Orion, with John W. Young and the Lunar Roving Vehicle visible in the background.

Middle: George R. Carruthers, principal investigator for the far ultraviolet

camera/spectrograph. Right: False color ultraviolet image of the Earth.

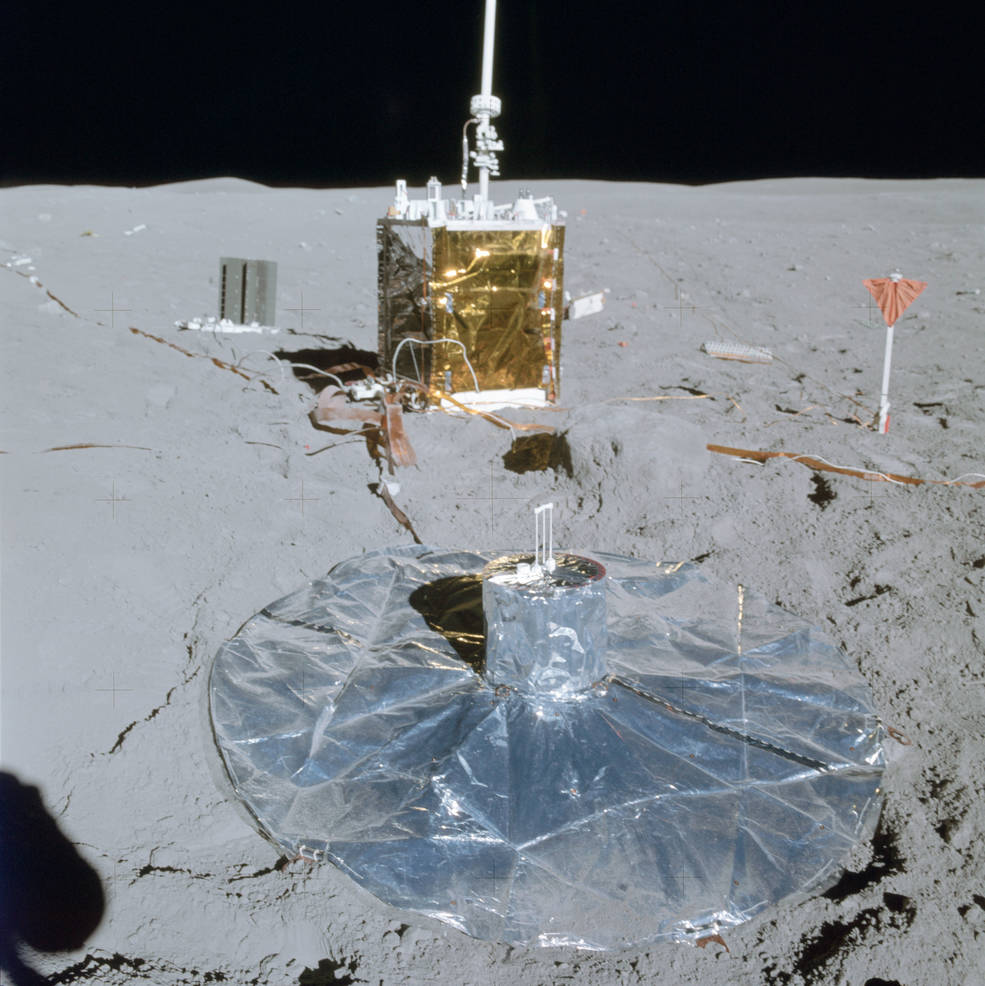

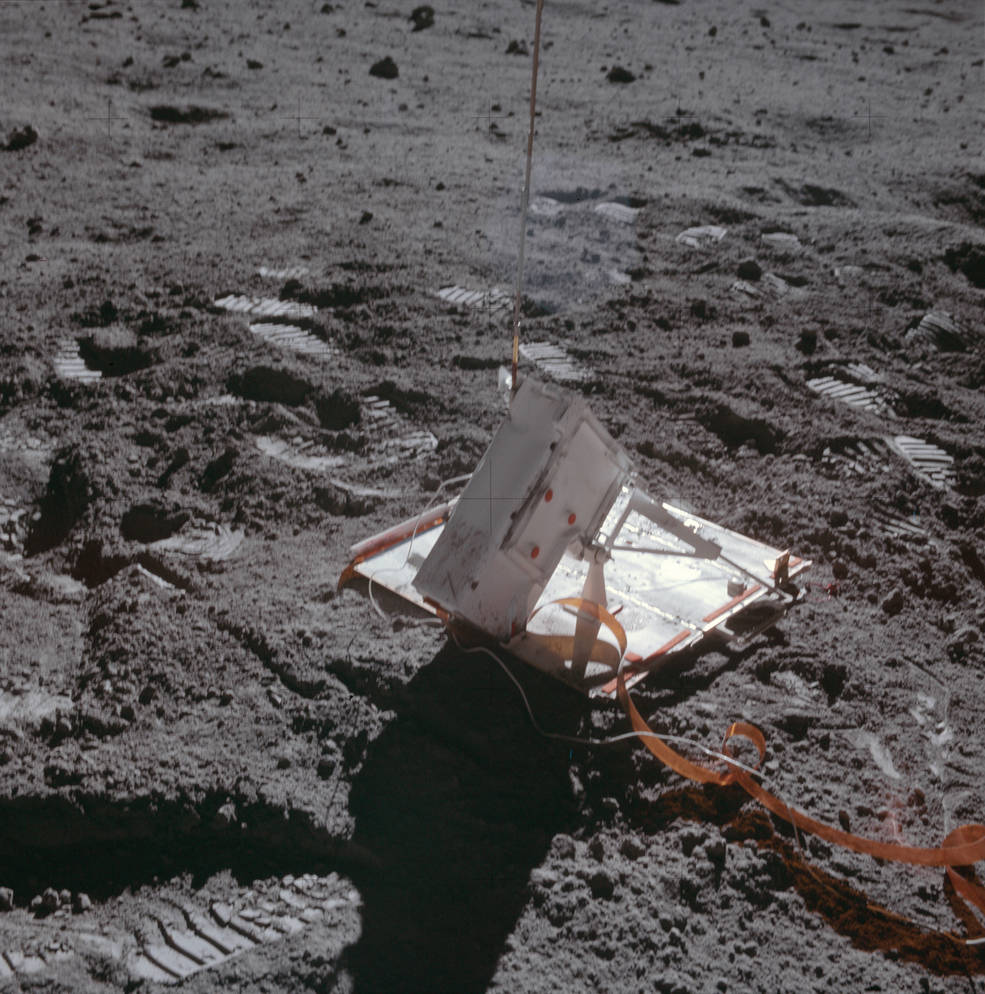

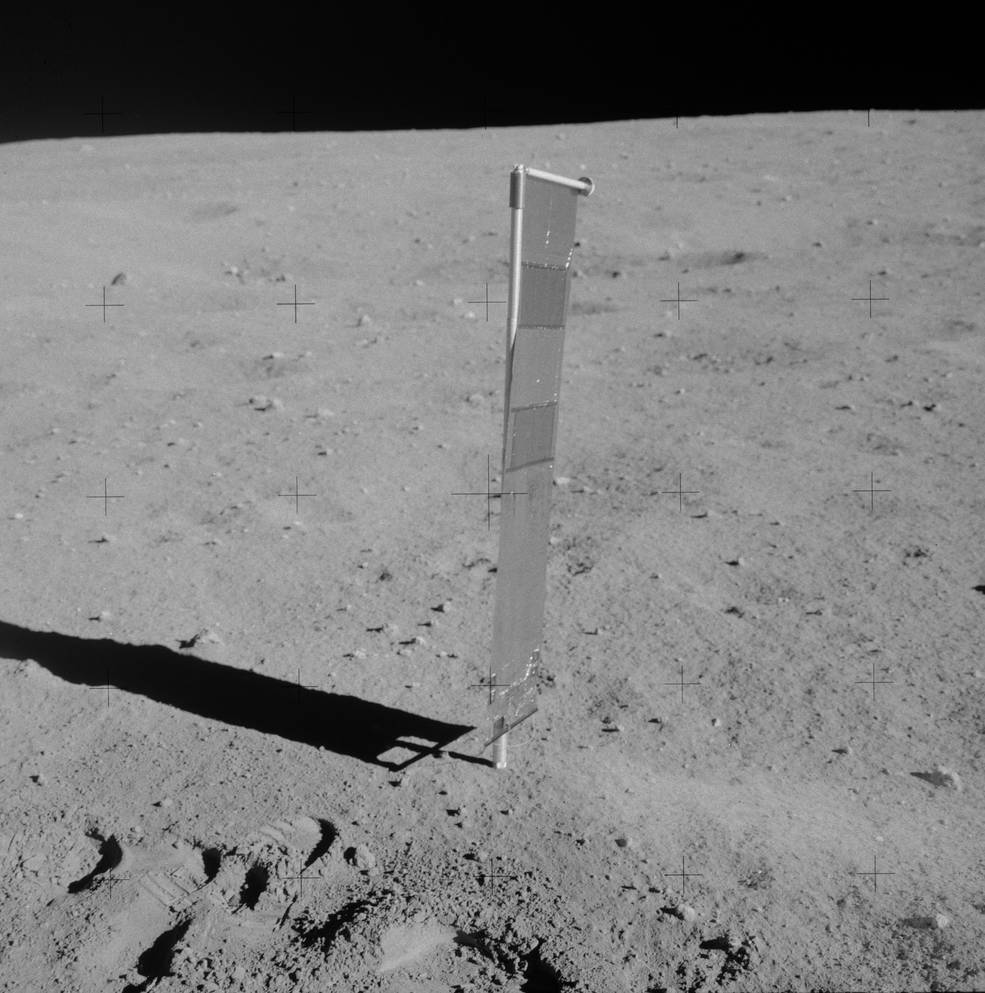

Young and Duke then proceeded to remove the components of the Apollo Lunar Science Experiment Package (ALSEP) from stowage on the LM. While Duke walked, Young drove the Rover to a site about 330 feet west of the LM, the only level area they could find, and they spent the next two and a half hours deploying the ALSEP instruments. In one mishap, Young accidentally disconnected the cable for the Heat Flow Experiment, resulting in a complete loss of data. Duke then took a 2-meter-deep core sample and both collected several rock samples.

The instruments of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP) deployed at Descartes. Left: The Passive Seismic Experiment, foreground, the ALSEP Central Station, middle ground, and the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, background. Middle left: The mortar pack of the Active Seismic Experiment. Middle right: The Lunar Surface Magnetometer experiment, with astronaut John W. Young and the Central Station in the background. Right: The Heat Flow Experiment.

Young and Duke boarded the Rover for the 0.9-mile drive west to Plum Crater, their first sampling station. Driving westward proved difficult, since the low Sun angle at their backs washed out details such as undulations in the terrain, small craters, and even rocks. Young parked the Rover on the rim of Plum crater. He and Duke began photographing the area and collecting rock and soil samples. Monitoring the Moonwalk via the TV camera, scientists in MCC saw a football-sized rock with a white top and instructed the astronauts to collect it. At nearly 26 pounds, it turned out to be the biggest single rock returned from the Moon by any Apollo mission, and the astronauts nicknamed it “Big Muley,” after William R. “Bill” Muehlberger, principal investigator for Apollo 16 geology and one of the geologists who had trained them before the mission. Young and Duke boarded the Rover and began heading back toward the LM, making a short stop at Spook Crater to take some measurements with the Lunar Portable Magnetometer and take a few rock samples.

Left: View of a partially buried rock near Plum Crater. Middle: Astronaut Charles M. Duke on the rim of Plum Crater, with the Lunar Roving Vehicle in the background. Right: In a still frame from the TV downlink, Duke picks up “Big Muley,” the largest rock brought back from the Moon.

Left: View of the Lunar Portable Magnetometer deployed near the Rover at Spook Crater. Middle: View from the Rover during the drive back to the Lunar Module (LM), with Spook Crater in the foreground and Stone Mountain in the distance. Right: The Solar Wind Composition experiment deployed near the LM.

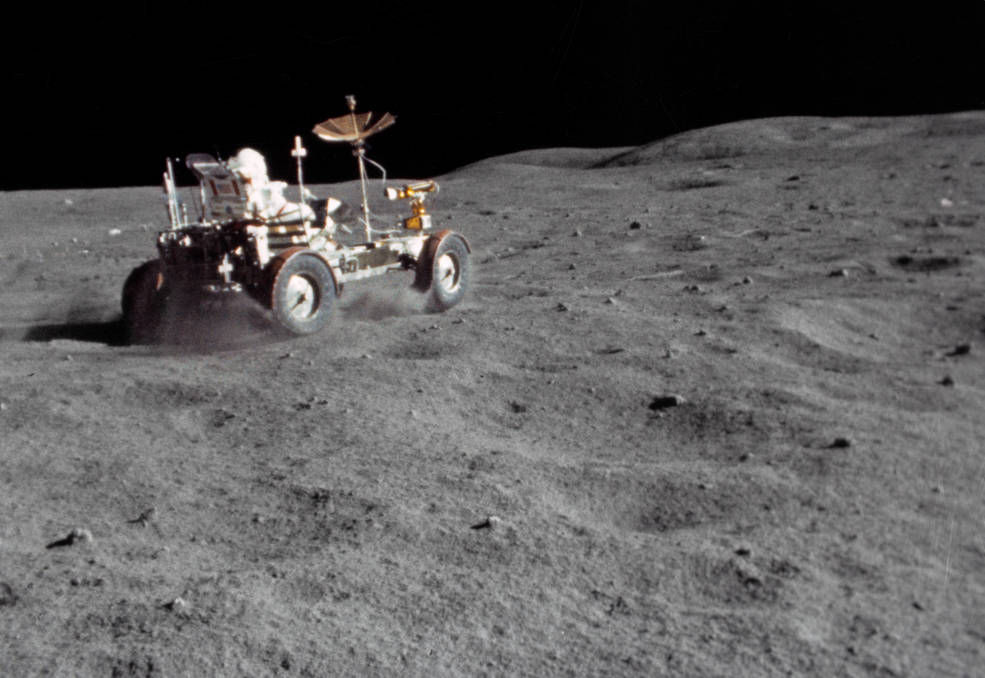

Back at the LM, Duke disembarked from the Rover and filmed Young driving it over the undulating terrain, kicking up rooster tails of dust with all four wheels, bouncing in and out of craters. The astronauts nicknamed this event the Grand Prix. Duke set up the Solar Wind Collection experiment near the LM, retrieving it at the end of the third Moon walk for return to Earth. Young parked the Rover and the two gathered all their samples before heading up the ladder into the LM. The first Apollo 16 Moon walk lasted 7 hours, 11 minutes, and they drove the Rover 2.6 miles. They pressurized the LM, took off their spacesuits, ate a well-deserved meal, and prepared for a good night’s sleep.

Still image from the film of astronaut John W. Young during the Grand Prix, a demonstration of the Lunar Roving Vehicle’s driving capabilities.

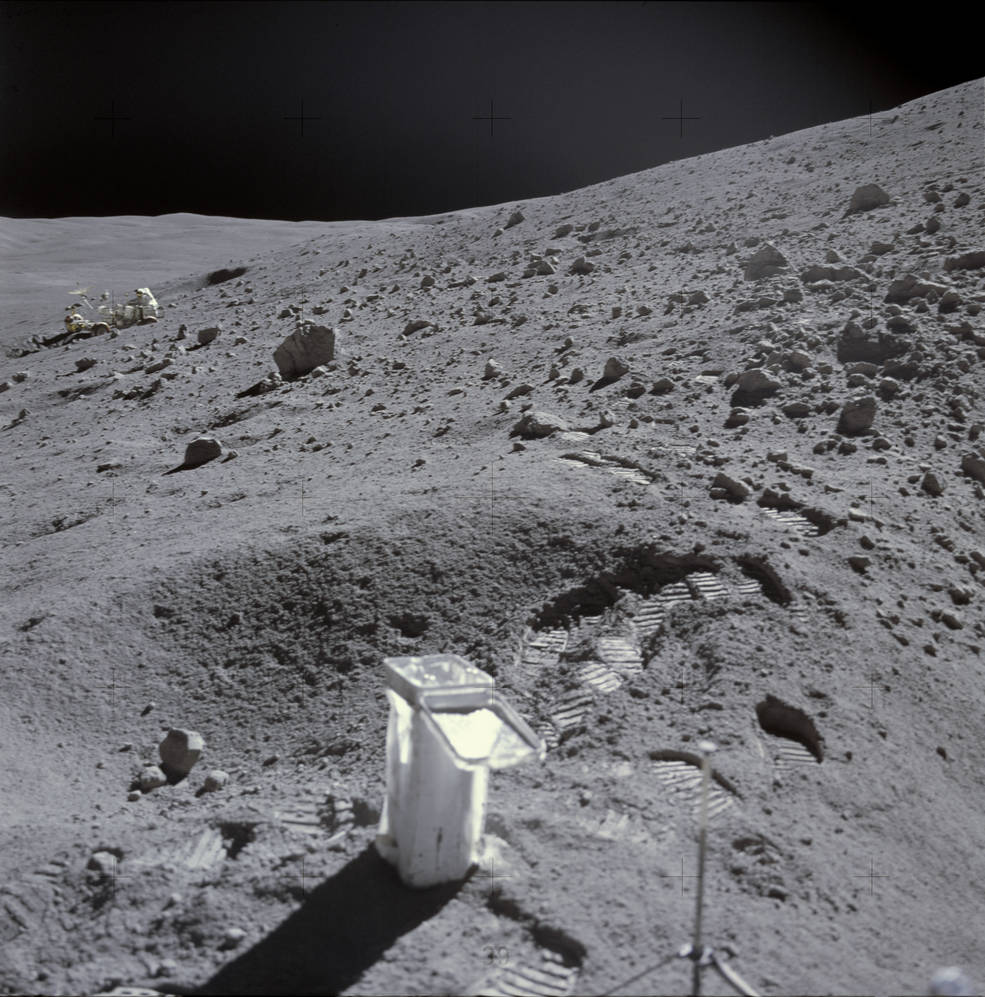

Young and Duke awoke the next morning and prepared for their second traverse, this time south to the slopes of Stone Mountain. Once back down on the surface, they loaded up the Rover and began the 3.2-mile drive to the first sampling station of the traverse, sometimes driving up slopes as steep as 22 degrees. They kept up a running commentary during the drive, describing the terrain as they drove through it. They parked the Rover on the slope of Stone Mountain, and from their vantage point could see their LM down on the plain 2.5 miles away and 430 feet lower in elevation. The work on the slope to collect rock samples, a core sample, and a soil trench sample proved to be the most difficult of the entire mission.

Left: The Lunar Module Orion, the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), and astronaut John W. Young in the background at the beginning of the second lunar traverse. Middle: Astronaut Charles M. Duke prepares to take a sample on the slope of Stone Mountain. Right: Duke is working near the LRV, visible in the distance, parked on the slope of Stone Mountain, with a sample collection kit in the foreground.

They made two more stops on the drive back down Stone Mountain, where Young found a young-looking crystalline rock. From that stop, they drove half a mile west across the plain to sample ejecta material from South Ray Crater. During this stop, Young’s suit caught on the right rear fender of the Rover, tearing it off, making the problem with lunar dust worse on subsequent drives. Their next drive took them northeast to their last stop, where they collected additional samples, including of soil from beneath a rock they overturned. From there, they drove back toward the LM to the ALSEP area for further rock and core sample collections. Duke jogged back to the LM, while Young drove the Rover, parking it near Orion. They gathered up their samples, headed up the ladder, and repressurized the LM. This second Moon walk lasted 7 hours, 23 minutes, the longest to that time, and they drove the Rover for 6.9 miles.

Images of large rocks at three different sampling stations during the second Moonwalk. Note the astronauts moved the third rock to obtain a sample of soil from beneath it.

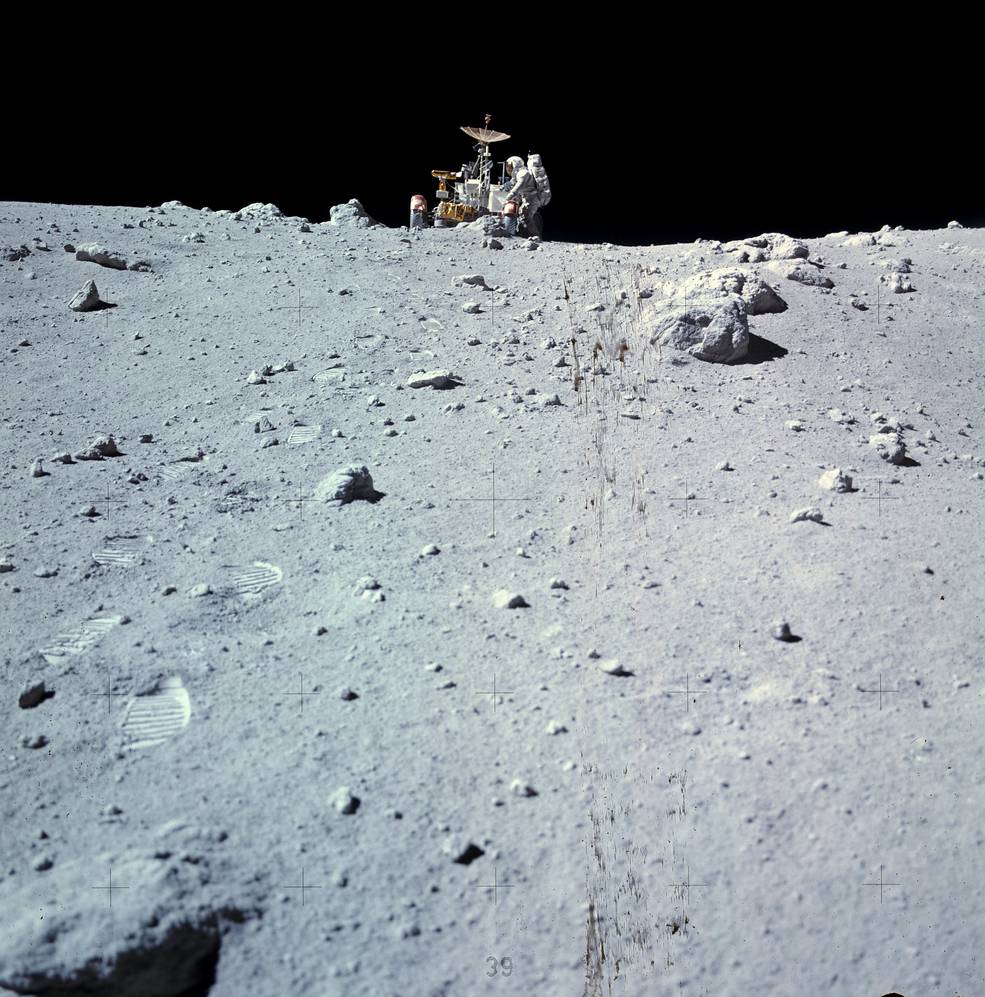

Because of the delayed landing, mission managers shortened the third and final Moonwalk from the planned seven hours down to five. During this traverse, Young and Duke planned to travel four miles north to explore the area around North Ray Crater, the largest crater – 1,500 feet in diameter and two hundred feet deep – explored by any Apollo crew. They egressed the LM and quickly packed the Rover for the drive north, making good time since the terrain had fewer boulders than on the previous day’s drive. They parked on the rim of North Ray Crater, near an 80-foot boulder they dubbed House Rock, with a smaller boulder named Outhouse Rock next to it. After taking some samples, they headed for their next stop about a third of a mile south back the way they came, setting a new lunar speed record of 10.6 miles per hour when traveling down a 15-degree slope. At a large boulder named Shadow Rock, Duke took a soil sample from a permanently shaded area, getting on his hands and knees to crawl under the rock’s overhang. Having secured these unusual samples, Young and Duke boarded the Rover and headed back toward the LM, stopping near the ALSEP site to collect more samples including a deep core.

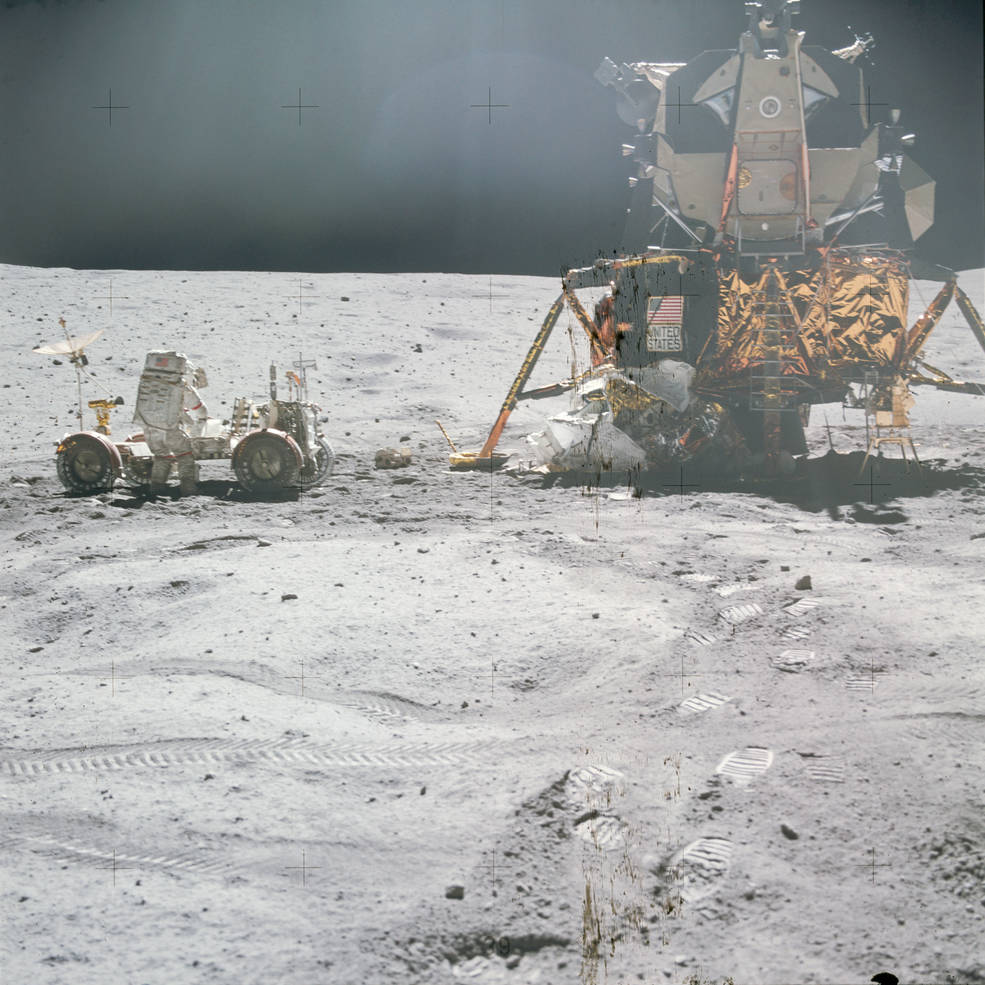

Left: Astronaut John W. Young loads up the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) at the start of the third lunar excursion. Middle: Astronaut Charles M. Duke stands next to the LRV on the rim of North Ray Crater. Right: Duke taking a sample from Outhouse Rock.

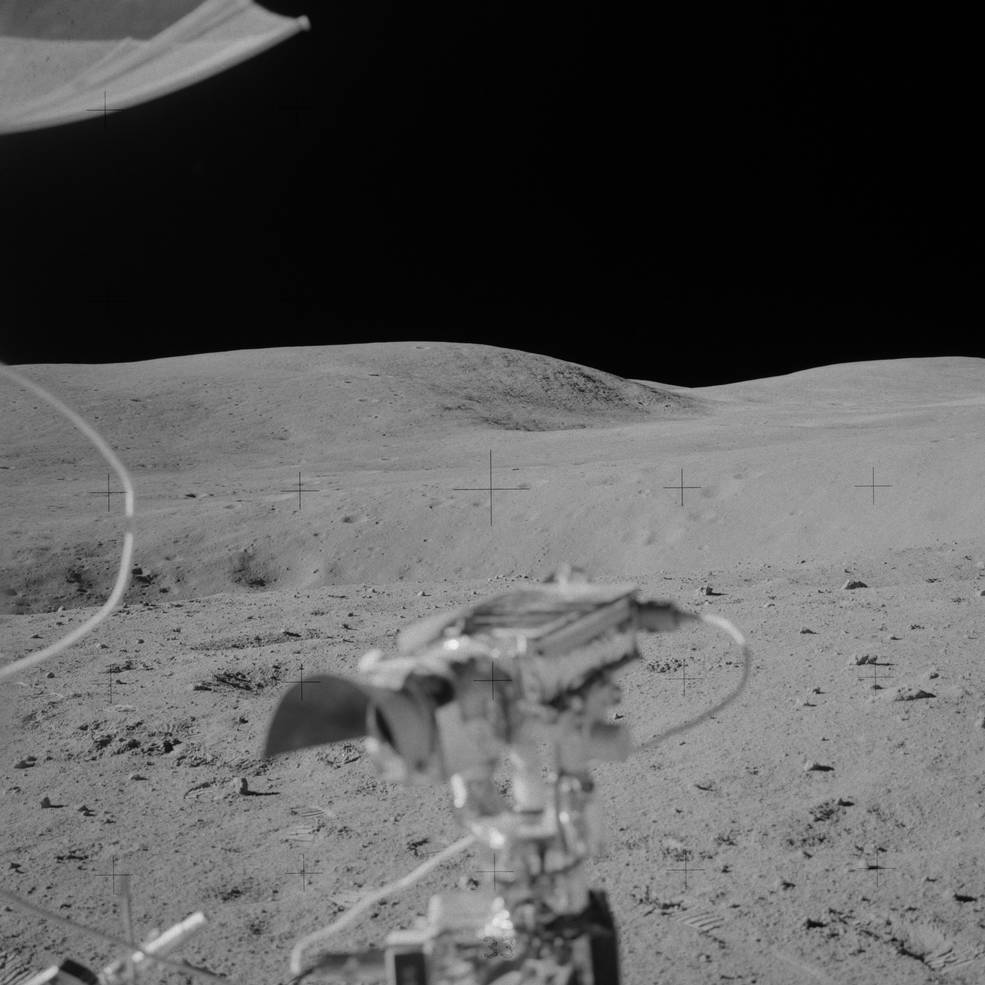

Left: Astronaut John W. Young peers under the Shadow Rock overhang. Middle: Young unloading the Rover at the end of the third Moonwalk. Right: View of the Lunar Module Orion from the final position of the Rover, ready to observe the liftoff.

Duke left a photo of his family, a piece of beta cloth with “64-C” written on it to commemorate his U.S. Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School class, and a medallion commemorating the 25th anniversary of the founding of the U.S. Air Force. Due to lack of time, Young and Duke decided not to perform the Descartes Olympics – in tribute to 1972 being an Olympic year – a planned set of activities to demonstrate sports such as high jumps and long jumps in the low lunar gravity. More informally, Young did five high jumps, reaching a height of 2.3 feet. Duke also attempted a high jump, to a height of 2.7 feet, and ended up falling over backwards, without injury or damage to his suit. After retrieving the SWC experiment, Duke threw the no-longer-needed support pole like a javelin. Young parked the Rover 300 feet east of the LM, from where its TV camera later observed the liftoff, while Duke started taking samples up the ladder. Young jogged back to the LM to help Duke with the loading. They both climbed up the ladder one final time, closed the hatch, and repressurized the LM, in preparation for liftoff three hours later. This third excursion lasted 5 hours, 40 minutes, bringing their total time outside the LM to 20 hours, 14 minutes. They drove the Rover for seven miles, for a mission total of 16.7 miles.

Left: Photograph of the Charles M. Duke family, left on the lunar surface. Middle left: A piece of beta cloth with “64-C” written on it, to commemorate Duke’s U.S Air Force flight school class. Middle right: Duke left a medallion on the lunar surface to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the founding of the U.S. Air Force. Right: In Mission Control, NASA flight surgeon Dr. John F. Zieglschmid, left, describes the medical data received from the Apollo 16 crew with Dr. William W. Duke, twin brother of Apollo 16 astronaut Charles M. Duke, and Dr. T. Sterling Claiborne, astronaut Duke’s father-in-law.

Composite panorama of the Apollo 16 landing site.

To be continued…