With just three weeks remaining until the launch of STS-1, workers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) continued to prepare space shuttle Columbia for its historic first mission. Workers at Launch Pad 39A finished repairs to the external tank’s insulation ahead of two tanking tests to verify the integrity of the foam. On March 19, 1981, controllers in the Launch Control Center (LCC) and STS-1 astronauts Commander John W. Young and Pilot Robert L. Crippen participated in the two-day dry Countdown Demonstration Test (CDT), essentially a dress rehearsal of the countdown to launch, then expected to occur around April 7. Tragically, after the conclusion of the CDT, an accident on the pad ultimately claimed the lives of three technicians conducting inspections in Columbia’s aft compartment.

Left: STS-1 astronauts John W. Young, left, and Robert L. Crippen enjoying the traditional

prelaunch,or in this case, pre-Countdown Demonstration Test (CDT), breakfast in the crew

quarters. Middle: Crippen, left, and Young suiting up for the CDT. Right: Crippen, left,

and Young walk out of the crew quarters building to take the ride out

to Launch Pad 39A.

On March 23, workers at Launch Pad 39A completed a two-week effort to repair debonded foam insulation on the external tank (ET). The three areas of debonding resulted from a test in January during which engineers pumped super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen into the ET. Following the repairs, engineers planned to conduct two additional tanking tests in late March to ensure the debonding did not recur prior to clearing the ET for Columbia’s first launch.

Left: At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, controllers in the Launch

Control Center’s Firing Room 1 monitor the dry Countdown Demonstration Test (CDT).

Right: STS-1 astronauts John W. Young, left, and Robert L. Crippen talk to

reporters after the conclusion of the CDT.

The dry CDT began March 17 with controllers staffing their consoles in the Launch Control Center’s Firing Room 1. The CDT was called “dry” because, unlike the prelaunch countdown, engineers did not fill the shuttle’s ET with super-cold propellants. Early on March 19, in crew quarters at KSC, Young and Crippen enjoyed the traditional breakfast and donned their pressure suits as they would on launch day. They rode the Astrovan to Launch Pad 39A and took their seats in Columbia’s flight deck. The CDT continued without any significant issues, concluding at the time of the main engine ignition. Launch Director George F. Page said at a news conference after the test, ”Everything, in general, went very well with the countdown demonstration. I think everybody was pleased with today’s run.” He declared the launch team ready to support the upcoming launch.

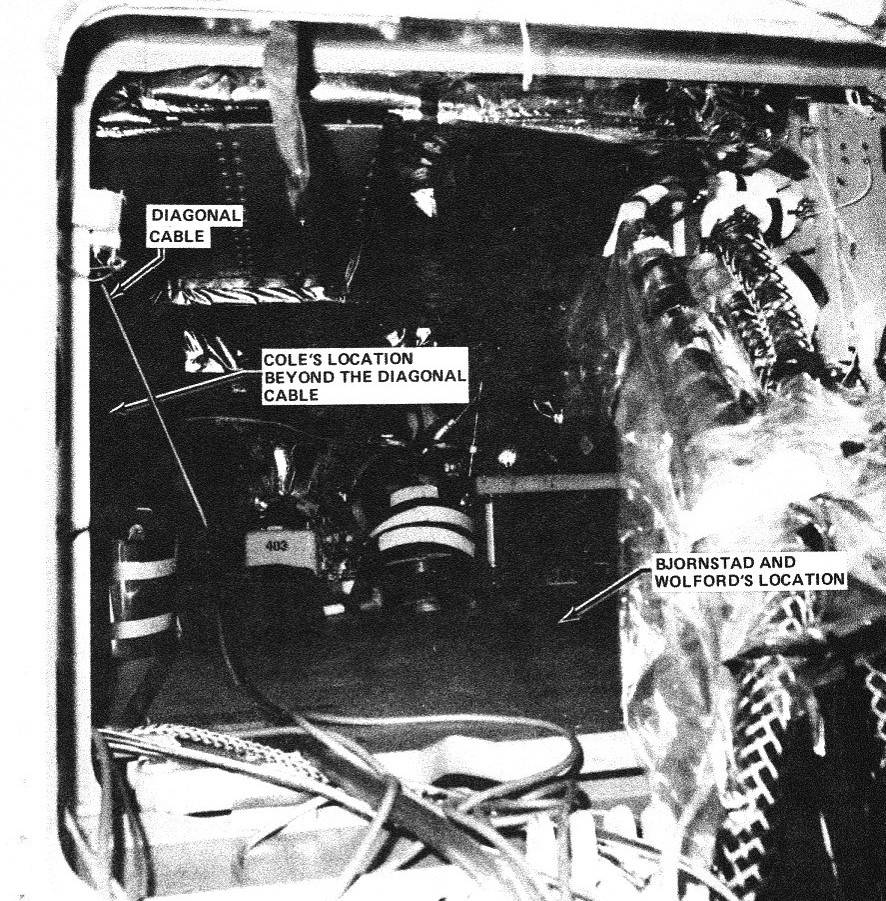

Left: Photograph showing the access to the aft compartment of space shuttle

Columbia where the accident occurred on March 19, 1981. Right: View inside

Columbia’s aft compartment, the site of the tragic accident

The CDT was considered complete as soon as Young and Crippen exited the vehicle. Technicians soon returned to the pad to begin their work, including inspection of Columbia’s aft compartment near the vehicle’s main engines. Normally, this area was purged with gaseous nitrogen during the countdown to prevent the buildup of potentially dangerous concentrations of gaseous hydrogen or oxygen, and the gaseous nitrogen was replaced with air once the test ended. But for this test, engineers requested that the gaseous nitrogen purge continue to evaluate a possible leak in the system. Managers approved the request, but since it was not considered hazardous, it did not undergo a safety review, and the pad technicians were unaware the purge was still underway. As they entered the aft compartment, unaware of the risk, technicians John Bjornstad, Nicholas “Nick” Cannon, and Forrest Cole were quickly overcome by the lack of oxygen. Technicians William Wolford and J.L. “Jimmy” Harper tried to help and were also affected. Rescuers airlifted Bjornsted to a hospital, but he died en route. Cole never regained consciousness and died in the hospital on April 1. Mullon survived but died in 1995 of long-term complications from the accident. They were the first fatalities associated with launch pad operations since the Apollo 1 fire in January 1967.

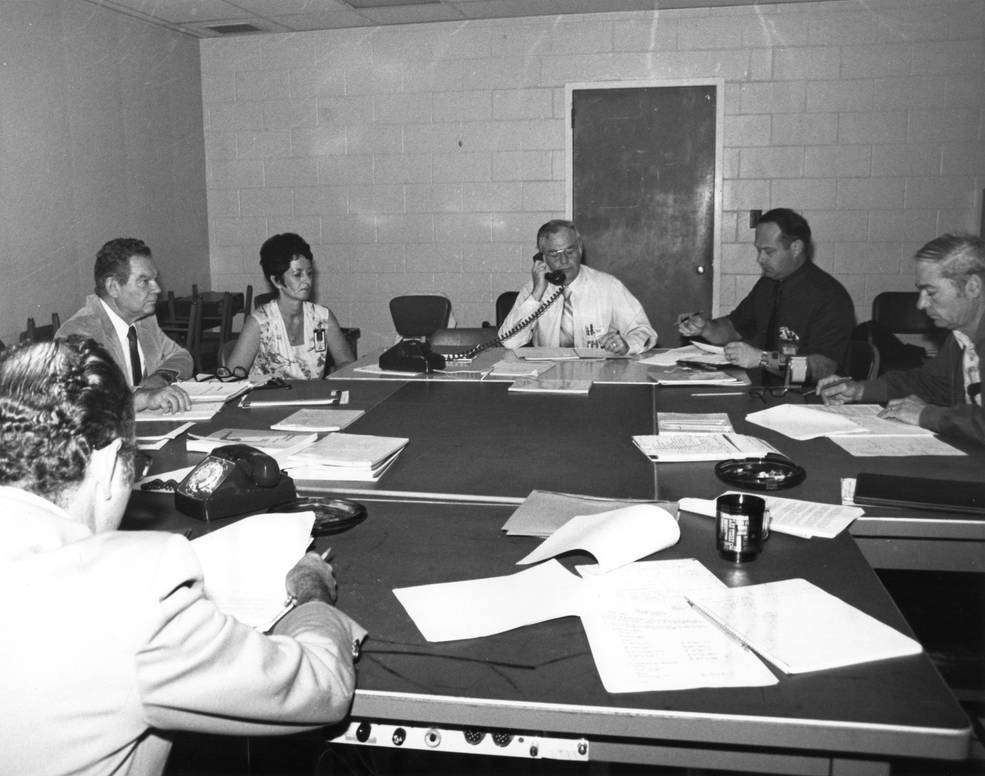

Left: Technicians John Bjornstad, left, Nicholas “Nick” Mullon, and Forrest

Cole working in Columbia’s aft compartment during an earlier test. Image

credit: Denise Mullon. Right: Charles D. Gay, director of expendable

vehicle operations at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, center

talking on the telephone, chairs a meeting of the mishap board.

NASA established a mishap investigation board chaired by Charles D. Gay, director of expendable vehicle operations at KSC. The board’s report, released on June 19, 1981, concluded that the proximate cause of death was hypoxia caused by the aft compartment’s pure nitrogen environment. The report cited organizational and process failures that allowed the technicians to enter the aft compartment in the first place and the lack of readily available rescue and resuscitation equipment near the work site as contributing factors. The report cited similarities between this accident and the Apollo fire, including not adequately addressing the hazards of the operations, poor organizational communications, and lack of proper rescue capabilities. It should be noted that inaugural missions of spacecraft are particularly susceptible to accidents.

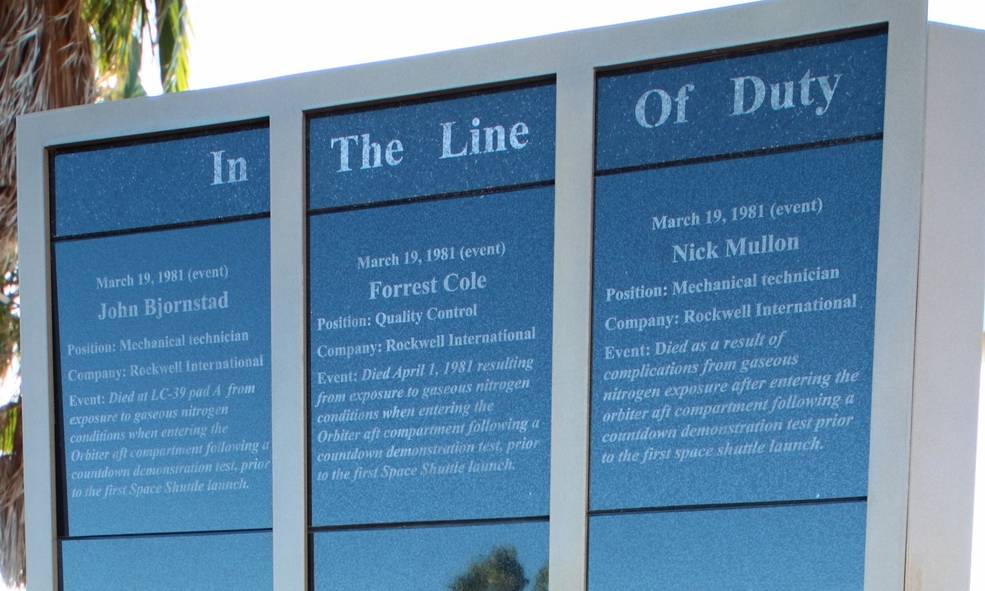

Left: The memorial at the Space Walk of Fame Museum in Titusville, Florida,

dedicated to space workers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center who died in the

line of duty. Right: Close up showing the names of John Bjornstad, Forrest

Cole, and Nicholas Mullon, who died as a result of the March 19, 1981

accident at Launch Pad 39A

Once STS-1 reached orbit in April, Young and Crippen paid a personal tribute to the victims of the launch pad accident, saying, “I think it is only right that we mention a couple of guys that gave their lives a few weeks ago in our countdown demonstration test: John Bjornstad and Forrest Cole. They believed in the space program, and it meant a lot to them. I am sure they would be thrilled to see where we have the vehicle now.” Thirty years later, the Space Walk of Fame Museum in Titusville, Florida, erected a monument to honor space workers who died in the line of duty. Engraved along the top are the names John Bjornstad, Forrest Cole, and Nicholas Mullon.