On July 16, 2013, NASA astronaut Christopher J. Cassidy and Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano representing the European Space Agency began a planned 6-hour spacewalk outside the International Space Station. Cassidy and Parmitano’s excursion, known officially as EVA 23, or the 23rd U.S. Extravehicular Activity or spacewalk, conducted…

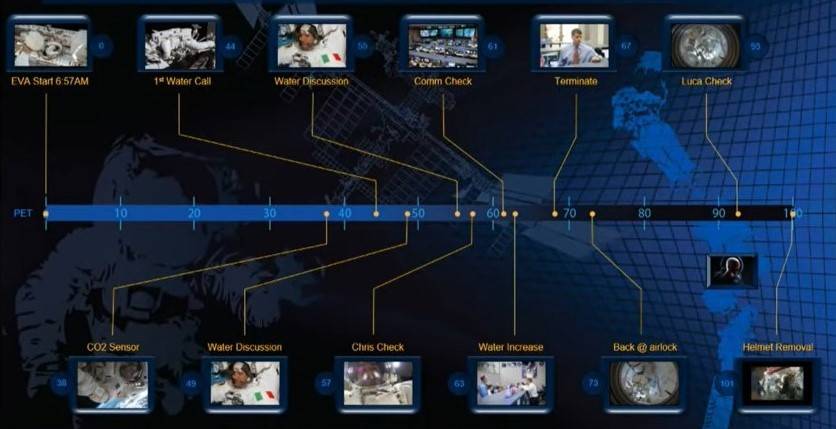

On July 16, 2013, NASA astronaut Christopher J. Cassidy and Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano representing the European Space Agency began a planned 6-hour spacewalk outside the International Space Station. Cassidy and Parmitano’s excursion, known officially as EVA 23, or the 23rd U.S. Extravehicular Activity or spacewalk, conducted at the space station, began normally. But the situation changed when Parmitano reported feeling water inside his suit’s helmet. As the amount of water increased, and concerned about Parmitano’s safety, Mission Control terminated the spacewalk. In darkness and with water blurring his vision, Parmitano safely returned to the airlock, the normal excursion having turned into one of the most serious mishaps in the history of spacewalking. A Mishap Investigation Board (MIB) identified the causes of the incident, providing an opportunity to examine and correct processes. NASA applied the lessons learned from the mishap not only to spacewalks but across the board to present and future programs.

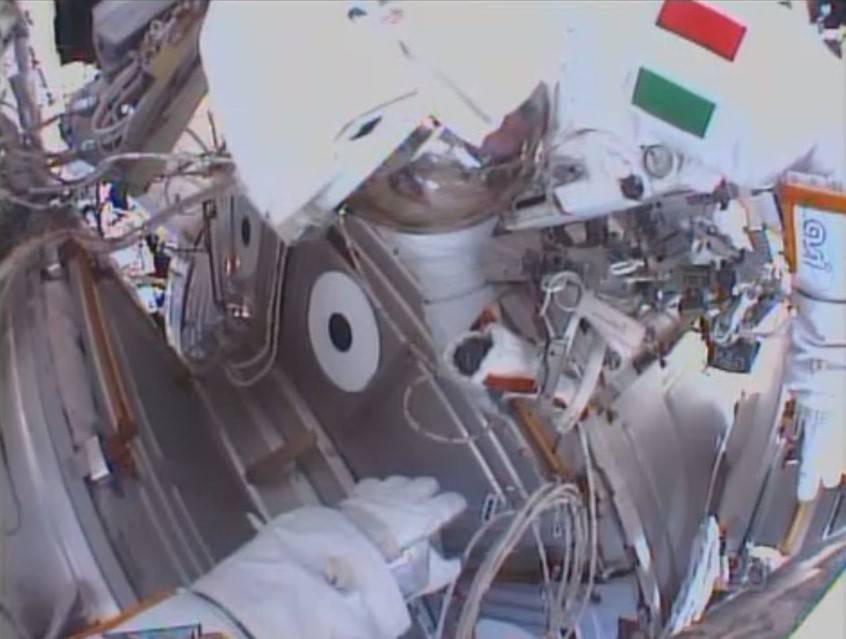

Left: NASA astronaut Christopher J. Cassidy, left, and European Space Agency astronaut Luca Parmitano in the airlock’s equipment lock before the start of EVA 23. Right: Parmitano working outside the space station at the start of EVA 23.

Having completed EVA 22 one week earlier, Cassidy and Parmitano’s preparations for this spacewalk went effortlessly and they began EVA 23 13 minutes early. Parmitano exited the airlock first, followed by Cassidy. Remaining anchored to the airlock by their 85-foot tethers, they set off in different directions to begin their first tasks, with Cassidy going up toward the Z1 truss while Parmitano translated down the Unity Node 1 module to connect cables to the Tranquility Node 3 module and then prepare cables for the upcoming Russian Nauka research module. In Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, a team of engineers led by Lead Spacewalk Flight Director David H. Korth monitored their activities, including Lead EVA Officer Karina Eversley, with NASA astronaut R. Shane Kimbrough serving as capcom, or capsule communicator.

The scene in Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston during EVA 23. Lead Spacewalk Flight Director David H. Korth is at center, capsule communicator (capcom) NASA astronaut R. Shane Kimbrough is standing at top, and Lead EVA Officer Karina Eversley is at top right.

Thirty-eight minutes into the spacewalk, as the astronauts completed their first tasks, and running ahead of the timeline, Parmitano called down that his suit’s carbon dioxide (CO2) sensor had failed offscale high. After a brief consultation, ground controllers decided this did not present any concern and told Parmitano to proceed with his cable routing task and to self-monitor for any signs of elevated CO2. Engineers did not consider the sensor failure an issue because it had failed on previous spacewalks. Engineers attributed those earlier failures, always occurring near the end of 6-hour spacewalks, to moisture from either sweat or condensation. However, a failure this early in the spacewalk should have alerted controllers to a more serious problem. In a phenomenon called normalization of deviance, everyone accepted the sensor failure as normal based on previous experience, without questioning the timing of the failure or its possible cause.

Timeline of EVA 23 highlighting the major events. Image credit: Courtesy NASA/Christopher P. Hansen.

Six minutes later, at 44 minutes EVA elapsed time, Parmitano reported to Cassidy and Kimbrough, “FYI, I feel a lot of water on the back of my head, but I don’t think it’s leaked from my [drink] bag.” The drink bag, located inside the front of the spacesuit, could hold up to 32 ounces of water. At this time, he did not sound overly concerned about the water, reporting it for information, and continued his cable routing task. Four minutes later, at 48 minutes elapsed time, Kimbrough asked Parmitano to provide more information on the water intrusion. While he continued the cable routing, Parmitano again described feeling a lot of water on the back of his head, with no change in quantity, and that he couldn’t identify the source but guessed it may have come from his drink bag and somehow made it to the back of his helmet. He reported no water on the front of the helmet. The entire discussion lasted about one minute. Parmitano moved on to perform a test to see how far he could reach into the confined space where three space station modules converged. Cassidy, having finished his task on the Z1 truss, translated to Parmitano’s location to provide an overview of the reach test.

Left: Image from Cassidy’s helmet camera of Parmitano performing the reach test. Right: Image from Cassidy’s helmet camera as he inspects the water in Parmitano’s helmet.

At 54 minutes, Parmitano reported without prompting that it “feels like a lot of water,” and Cassidy, now next to him, visually confirmed this. Parmitano, in a reference to the end of EVA 22 when his helmet contained about one-half liter of water, said it felt like about the same amount. Cassidy told Parmitano to drink the remaining water in the drink bag to eliminate it as a source of the leak. But the amount of water increased even after Parmitano drank the drink bag dry. Kimbrough instructed them to stop work while the Mission Control team assessed the problem. Cassidy and Parmitano took the opportunity to take photographs of each other while they awaited further instructions.

At 58 minutes elapsed time, Parmitano declared that he no longer thought the water came from the drink bag, with Cassidy questioning whether it could be sweat or urine. Parmitano replied that he couldn’t possibly sweat so much. Four minutes later, at 62 minutes, Parmitano requested a radio check with Cassidy because he believed water had intruded into his communications cap. Parmitano pondered the Liquid Cooling and Ventilation Garment (LCVG), worn inside the spacesuit with tubes of water running through it to cool the astronauts during spacewalks, as a possible source of the water, but Mission Control considered that a low likelihood. Parmitano added that he now believed the water was increasing. Upon hearing that, Korth, Eversley, and the rest of team decided to terminate the spacewalk, 23 minutes after the first report of water in the helmet.

At 67 minutes, Kimbrough informed the crew of the decision, instructing Parmitano to make his way back to the airlock and Cassidy to await instructions for his return to the airlock. As he began his translation to the airlock, Parmitano asked Cassidy if he could identify the path for him since water in his eyes now obscured his vision. Because their tethers anchored them back to the airlock, each astronaut had to retrace the steps he took at the start of the EVA, meaning Cassidy could not help Parmitano find his way. As he turned his body to return to the airlock, the motion caused the water to shift from the back of his head to his face, covering his eyes, ears, and nose. To make matters worse, the space station at that moment entered into orbital night, and Parmitano could only see the small area illuminated by his headlamps. In darkness and with blurred vision, Parmitano used his tether to feel his way to the airlock. The water in his communications cap resulted in intermittent contact with Cassidy and with Mission Control, making them less than fully aware of the seriousness of Parmitano’s situation.

Left: View from Luca Parmitano’s helmet camera as he arrives back at the airlock, illuminated only by his suit’s headlamps. Middle: View from Parmitano’s helmet camera as he prepares to enter the crew lock. Right: View from an external space station camera as Parmitano enters the crew lock head first.

At 72 minutes, Parmitano reached the airlock, reporting lots of water that now covered his ears, eyes, and nose, forcing him to mouth-breathe. Five minutes after Parmitano, Cassidy arrived at the airlock, went inside, and at 87 minutes closed and locked the crew lock hatch. Three minutes later, from inside the equipment lock section of the airlock, NASA astronaut Karen L. Nyberg began repressurizing the crew lock, a process that cannot be done too quickly or the two spacewalkers would not be able to keep their eardrums from bursting from the rapid pressure change. Parmitano had difficulty clearing his ears during the repressurization since the Valsalva device normally used to plug his nose had become wet and detached from the visor. He had difficulty hearing Mission Control when they requested a status check, so Cassidy peered into his helmet, and squeezing Parmitano’s hand, reported that “he looks miserable but ok.” Once the crew lock reached full pressure, Russian cosmonaut Fyodor N. Yurchikhin opened the hatch and he, Nyberg, and cosmonaut Pavel V. Vinogradov pulled Parmitano into the equipment lock. Using an expedited procedure, 100 minutes after the start of the spacewalk and 56 minutes after the first report of water, they removed his helmet and began to towel him off, with drops of water escaping from the helmet as they stowed it for later inspection and analysis.

Left: In the airlock’s equipment lock, NASA astronaut Karen L. Nyberg, right, assists Luca Parmitano seconds after removing his helmet. Right: NASA astronaut Christopher J. Cassidy’s photograph of Parmitano as Russian cosmonaut Fyodor N. Yurchikhin assists in removing his spacesuit.

During a debriefing with the crew a few hours after the spacewalk, Parmitano described his harrowing experience in great detail, giving ground controllers their first awareness of the real risk the water leak posed to his safety. He also provided additional clues to the source of the water by describing it as cold and as tasting funny or metallic, ruling out the drink bag and pointing toward the Portable Life Support System’s (PLSS) cooling system. Near the end of the spacewalk and in the airlock, the estimated 1.5 liters of water in the helmet caused intermittent failure of the communications system in addition to covering Parmitano’s eyes, ears, and nose. Cassidy, Nyberg, and Parmitano provided the media with their description of EVA 23 and Cassidy provided a more detailed explanation of the workings of the suit.

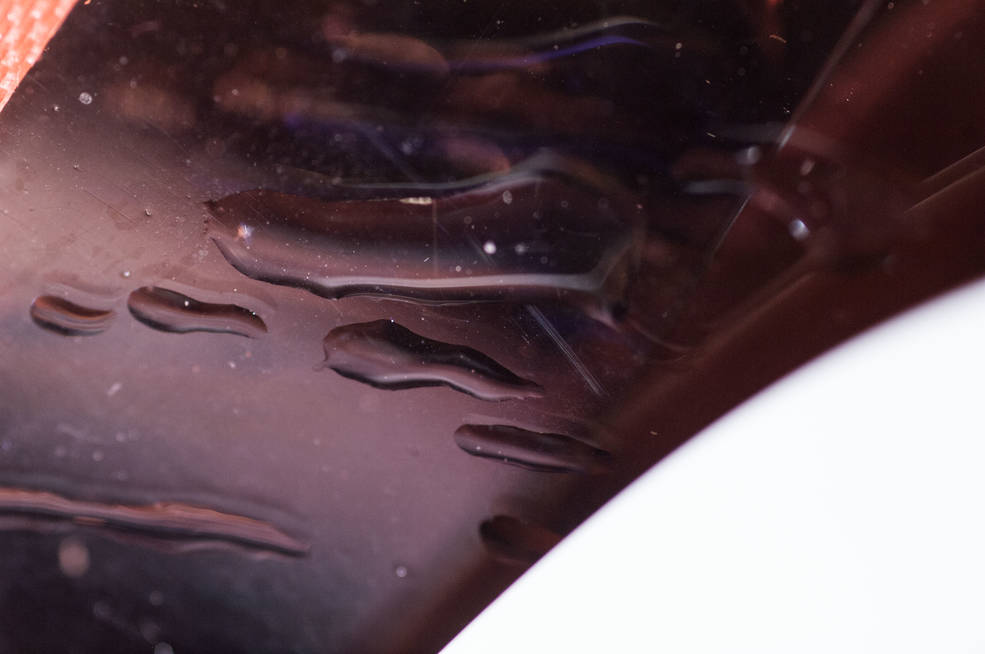

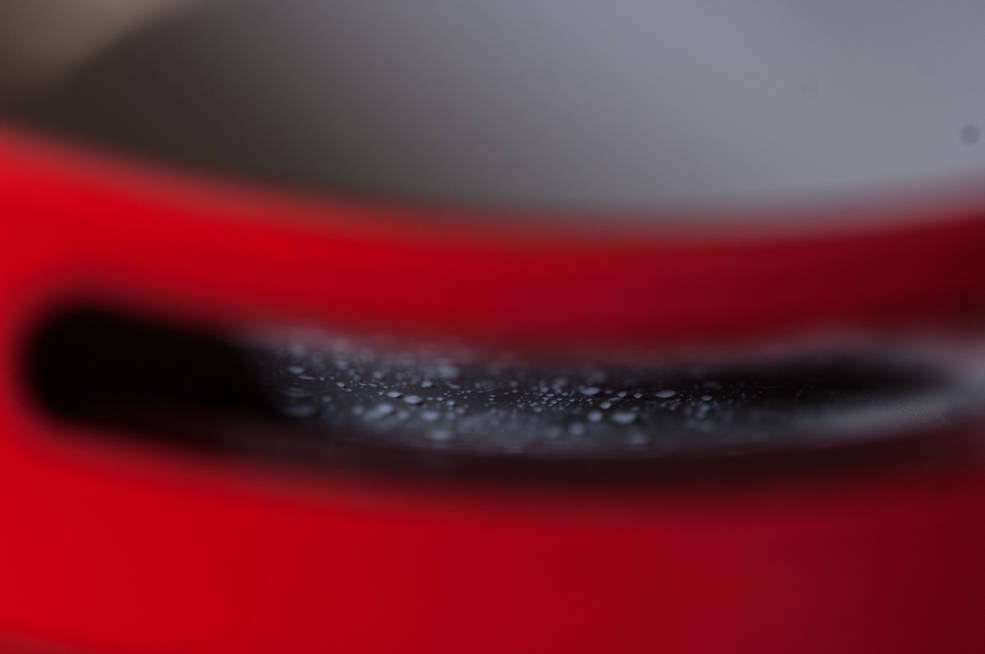

Left: Image of water in Luca Parmitano’s helmet following EVA 23. Middle: View of water droplets in the ventilation inlet of Parmitano’s helmet. Right: Image of the silicate buildup on the fan separator.

NASA classified the incident as a High Visibility Close Call and NASA Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations William H. Gerstenmaier established a Mishap Investigation Board (MIB) on July 22, chaired by Christopher P. Hansen, then chief engineer of the International Space Station Program. The MIB released its official report on Dec. 20, 2013, with a redacted version available to the public, although work still remained to fully identify the source of the material that led to the leak. That work took an additional six months. The astronauts tested the suit about one month after the EVA, and the leak recurred. The fan pump separator from the PLSS, considered a likely culprit for the mishap, was returned to Earth aboard a Soyuz spacecraft in November 2013 for postflight analysis.

In summary, the MIB found three causes that led to the mishap. Frist, a buildup of inorganic material caused blockage of the drum holes in the suit’s fan pump separator, resulting in water spilling from the cooling loop into the ventilation loop, and ultimately into the helmet. The origin of the contamination turned out to have an extremely complex 10-year history that wasn’t fully understood until months after the MIB report’s release. Second, the NASA team lacked the knowledge of this particular failure mode. And third, the team misdiagnosed the failure when it first occurred during EVA 22. The report stated that both the ground team and the astronauts responded appropriately given the information available to them. Cassidy and Parmitano’s backgrounds certainly helped them deal calmly with the emergency – before their selection as astronauts, Cassidy served with the U.S. Navy SEALs and Parmitano served as a test pilot in the Italian Air Force.

The MIB identified five root causes that contributed to the suit failure. First, with the priority placed on using crew time for research on the space station, engineering teams felt reluctant to ask for time to troubleshoot engineering issues. Therefore, no investigation of the water leak on EVA 22 took place. Second, a perception existed that drink bags leak, causing the community to easily accept that as the cause of the water leak, when in fact this variant of the drink bag never leaked. Third, ground teams perceived that anomaly investigations result in lengthy and resource intensive activities, making them reluctant to invoke them. Fourth, although engineers understood the behavior of liquids in weightlessness, they had less insight into how liquids behave in complicated systems like the suit cooling mechanisms, meaning they did not anticipate the specific failure mode that occurred. And fifth, small amounts of water in spacesuit helmets had occurred in the past, caused by sweat or condensation, and therefore perceived as normal by ground teams. This normalization of small amounts of water in the helmet led to a slower than desired response to Parmitano’s initial reports.

Left: Christopher J. Cassidy points out the ventilation port in Luca Parmitano’s spacesuit helmet, where the water entered. Right: Parmitano’s suit during an on-orbit test, showing water droplets on the visor.

In addition to the root causes, the MIB identified three proximate causes that led to the incident. First, the space station program proceeded to conduct EVA 23 without understanding the spacesuit failure that occurred on EVA 22. Without thoroughly investigating the problem on that earlier spacewalk, teams arrived at the consensus that the crew drink bag caused the leak. As a solution, the astronauts replaced the drink bag for EVA 23. Later analysis showed that neither bag had a leak. Second, a large amount of water had accumulated inside the spacesuit’s helmet originating behind the astronaut’s head and causing a potentially life threatening condition. And third, because of a poor understanding of the suit failure mode in both EVA 22 and EVA 23, the flight control team and the astronauts failed to terminate the spacewalk after the first report of water in the helmet.

The MIB’s report included 49 recommendations to help prevent a recurrence of the EVA 23 incident. As a result, the space station program implemented hundreds of changes to processes and procedures, not only in the spacewalking arena but across the board, to prevent a recurrence and to improve responsiveness to similar events. One example is how astronauts are routed during spacewalks so they could come to each other’s rescue without having to go separate ways to return to the airlock. Although the MIB did not release its report until Dec. 20, and NASA put a hold on planned spacewalks during the investigation, failure of an ammonia pump module that month required NASA astronauts Richard A. Mastracchio and Michael S. Hopkins to conduct two contingency spacewalks. By that point, the investigation had revealed the presence of material in the pump separator as the culprit, and the astronauts replaced the unit with a clean one. Hopkins wore the same suit as Parmitano and completed the two spacewalks without any issues. Mastracchio, wearing the same suit as Parmitano, and Steven R. Swanson conducted a third contingency spacewalk in April 2014 without issues. NASA cleared the suits for planned spacewalks in September 2014. Engineers added two mitigation items to the suit, a helmet absorption pad and a snorkel, to deal with a water leak, should one occur.

NASA Associate Administrator Gerstenmaier called the water intrusion mishap a “gift,” in that although Parmitano endured a stressful event, it did not result in injury or death, but served as a reminder of the importance of vigilance. Some of the lessons learned from the mishap echoed those learned from major accidents, such as the Apollo 1 fire and the Challenger and Columbia shuttle accidents. Among these are the normalization of deviance, the complacency that continued success can bring, and the importance of open communications. Engineers designing and building the next generation spacesuits for Artemis incorporated the lessons learned from this incident to prevent a similar problem from occurring. The lessons learned, especially those dealing with the risk culture, have applications not just in the spacewalking world but throughout NASA and indeed in institutions beyond the space agency.

Working with Space City Films, MIB chair Hansen, now serving as the deputy manager of the EVA and Human Surface Mobility Program at JSC, created a documentary about EVA 23. For more details about EVA 23, please watch Hansen’s presentation.

With special thanks to Chris Hansen for his review of the article and for his insightful comments.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center