We like to start with where you were born and grew up, your family at the time, your childhood, your mother and father, what they did, and especially if there was anything about that early time that got you curious about science and the things that you’re doing today professionally, so take it from there.

I was born and raised in San Francisco. I’m actually a fifth generation San Franciscan, although that’s only on one side of the family. It’s the fifth generation to have lived there, and the third generation to have been born there, because two generations moved there together.

That sounds almost like back to the gold rush! (laughs)

Not that era, but not long thereafter! My paternal grandmother’s parents, and one of her grandparents, came to San Francisco around 1870.

Well you certainly have long roots there then.

Yes. And from a small child I was always interested in numbers. I think that was the thing, that was the continuity and a big part of the reason that I went into science.

I saw that your undergraduate degree was in math, so that fits. How about your parents, what did they do, and did you have siblings?

My father was a pharmacist, he owned a small pharmacy in downtown San Francisco. He had one pharmacist employee and typically a few high school students who helped with the cash register and did most of the deliveries, and I worked there on and off, especially during summers, when I was that age and even a little bit before.

My mother was born and raised in Ohio, to immigrant (from Russia) parents. She went to college, at a time when very few women from the Midwest were going to college, during the Great Depression, but in her second year, she decided she wasn’t interested in college and dropped out. She then moved from Ohio to Detroit, became an auto worker, and got very active in the union. This was in the late ‘30s, early ‘40s, and she was in the Trotskyite wing of the UAW. A decade later, in the (Joseph) McCarthy era, there were people snooping around asking about her, but she had stopped being active in far left politics a long time before that. She came to San Francisco at some point for a vacation and loved it, and she moved to the city around 1950. She did administrative assistant work, fairly high-level administrative assistant things, although she stopped working for several years when I was born.

I had a half-sister from my father’s previous marriage. She was 17 years my senior and had one son, who was born six years after me and for various reasons they lived with us for about a year. My nephew was much more of a sibling to me than my sister was, as he and I were much closer in age. So I’m mostly an only child, but not entirely. My nephew and I even went to the same school for one year, riding on the same school bus in the mornings.

OK, so at some point you went to school and after grade school or high school, you needed to decide what to do about college. How did that go with you?

This was a different era, both in terms of what was going on and what high school kids knew about their options. I only considered four colleges, which wasn’t particularly unusual during that era. Nowadays, for students who are interested in going to a top-quality college, it’s totally different – I’ve had some high school students doing research with me recently for who applied to a large number of colleges. I applied to three and got into my first choice. Part of the reason I could afford to do that was that my “safety school”, the one I knew I could get into, was Berkeley. At that time if you had high enough grades and SAT scores and were a California resident, you were guaranteed admission.

What was your first choice?

MIT, which was where I went.

And you majored there in math?

Yes. I started out being a physics major, and at MIT there was a requirement for all students to take a lab course. You could get out of it by taking an econometrics lab, which wasn’t a laboratory lab, but I took a physics lab because I wanted to see what it was like. I found that I wasn’t that interested in it, and physics majors had to complete a very intensive junior year lab course, which I didn’t want to take. Therefore I switched to math because I realized that I only needed one more math course to get my math degree, so why bother taking the very time-consuming physics lab that I didn’t want to take? I was interested in mathematical physics, having gotten quite interested in physics in high school, so I was interested in science but not focused on a specific topic.

So you graduated from MIT with a degree in math and you had some choices to make: you could teach, of course, but you decided to continue and get a PhD. Can you tell us about that, what drove that decision?

Neither of my parents had bachelor’s degrees, because my father got his pharmacy degree when you didn’t need a bachelors and my mother didn’t go all the way through college, but education was still very much valued and it was pretty clear that I was going to get an advanced degree. And indeed eventually my half-sister, nephew and all of my first cousins have gotten advanced degrees of some type or another, including one who also got a PhD, a chemistry PhD, and like me, he got it at UC Berkeley. I grew up in San Francisco and to me Berkeley was what a college town was like, but Boston had the reputation of being the great American college town and that was part of my decision to go to MIT. I didn’t even consider Caltech because it was in Southern California in the middle of the smoggy area and that was a much worse time regarding smog than this era. As an undergrad, I found out that I was not particularly fond of winter, let’s put it that way, and I wanted to come back to the Bay Area. There were general areas of math and physics that I wanted to go into but I really hadn’t specialized that much, so I wasn’t yet sure what parts to pursue, thus I was interested in graduate schools that were top-notch at both.

Winter is a major difference between Boston and Berkeley, that’s for sure.

Definitely, definitely. I looked at two other possible graduate schools in terms of going to their campus, as I had done with four for undergrad. At Stanford the theoretical physics was pretty much particle physics and I had taken a freshman seminar at MIT on theoretical particle physics and I remembered the professor drilling into us the poor job market in theoretical particle physics, so I didn’t really want to go into that (laughs). There was one math professor at Stanford who did research that I found interesting, but he was about to retire.

So going into grad school is when you switched from math to physics?

Well, I visited Berkeley and talked with a few professors in math and physics who looked like they were doing interesting things, and there was one who was a professor with an appointment in both departments who said “choose math because then you’ll have much more flexibility in what you’re doing”. And one of the things that the Berkeley Math Departiment offered that most places didn’t was they accepted people for all three quarters, not just for autumn, so I could finish up my undergrad a half year early. It was the only place I was interested in that had midyear admission, which I wanted, so I could apply and if it didn’t work out I could still apply the normal time of year for the following autumn.

I was accepted and took both math and physics courses. I knew a lot of people in physics and I was taking one astrophysics course that was team taught by two people, one of whom was the Nobel laureate Charles Townes, who among other things invented the laser. In my first two quarters of grad school, I lived in International House and the majority of my friends were South Asians, just because of the demographics of the people who lived there.

South Asians? From southern China or the East Indies?

No, from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. And people from those countries were largely in the same group in International House, even though their countries didn’t have the best relations, let’s put it that way, as is the case now. And one of the students in this class I took, and it was just a few students, was from India and had just started grad school and I was going back and seeing friends in International House while he was living there, so with the double connection we talked a lot and he pointed me to a couple of professors in astronomy to talk with, in theoretical astronomy, so that’s how I drifted towards astronomy, although I had some interest previously. The first one I met seemed very good, very interesting, very bright, and the other one seemed even better. And I didn’t know what these people had done. The one who seemed even better, his name was Frank Shu, and as I later learned, his bachelor’s thesis was explaining why galaxies are spiral. He was second author on a two author paper with his advisor, but still that was pretty impressive for a bachelor’s thesis that he submitted before he turned 20.

For sure!

I didn’t know that at the time, but I was impressed just talking with him. The Math Department was very flexible in these things as long as you passed their exams.

So that tracks to your interest in astronomy and astrophysics so how about the path from your education to eventually winding up at NASA Ames?

OK. Well this interview is not all chronological, but this particular path will be. I’m going back now to first grade! (laughs)

You’re going to be the first that has a track to Ames from the first grade! (laughs)

My first grade teacher, her son had some accident or illness and was recovering from it and came in and taught us a module on planets. We made a model solar system, a big balloon for the Sun and papier-mâché planets, and I remember him talking about how the solar system was formed, the ideas back then, which actually weren’t current but might’ve been when his teachers were learning. My early interest in astronomy was also based in part on visits that my father and I took to the old planetarium at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, which in addition to showing the sky had a depiction of the SF skyline. An aside is that, in early 2003, I gave one of the last science talks in that planetarium prior to the closure of the museum in preparation for demolition and construction of a new building with the grander and more modern planetarium (alas lacking the historic skyline). Anyway, I was interested in planets from a very young age, although had never thought of it much as a career thing.

I grew up watching the space race. I have zero memories of the Mercury program, I’m too young for that, but I do remember the Gemini program. I remember the first crewed Gemini launch, back then we called it the “manned” launch, and they probably would have called it so even if the women who were trained to be astronauts had been sent to space, because the terminology, the use of the language, has changed from that period. I remember bringing my little transistor radio, transistor radios were new technology back then, and I was listening to it sometime when we were outside and one of the other boys asked me what the score was, thinking I was listening to the game! It was early on in the space race so I said it was Russia 2, the United States 1, because in terms of crewed programs the Soviet Union was still ahead of the United States. And I followed the Apollo program, I remember watching during the first lunar landing mission (Apollo 11) when the astronauts were going to go out for the moonwalk. We had three televisions in the house, two were black and white, one was color, but these were black-and-white pictures, and we brought them all into the same room and tuned each to a different network, two with the sound off, because we weren’t going to miss the pictures live from the Moon if one or two of the three networks had problems.

Then, when I was an undergrad, and had switched to a math major, I had a very good undergraduate advisor, not a thesis advisor but somebody who gave me good advice about taking courses from some very top notch scientists since I was considering a career in science. And I remember starting one of those courses and then dropping it because my course load that semester was just too much work, so I was going to take it the following year, that was on Earth science. Unfortunately for me, that professor was appointed National Science Advisor in the interim so I didn’t get to take it the next year. But the other course was on planetary science, taught by a couple of people, one of whom was one of the special extra-inspiring professors that had been recommended to me. I got very much into that class, and have kept in touch with that professor, even seen him when I’ve gone back to the Boston area a few times, and we have emailed a little during the pandemic. I’m probably going on too many asides, but I really liked the course. It was two semesters that could be taken in either order so I took both semesters before graduating, although I didn’t really consider it much of a career option. So that’s why I was going more for math or physics than astrophysics or planetary.

When I was at Berkeley the applied math tended to be fluid dynamics or numerical work, or proving theorems about differential equations, which to me had the negatives of both applied math and pure math combined into one. Then when I went toward astrophysics to take a look at that as something for a thesis option, maybe a career path, maybe not, there really wasn’t any planetary at Berkeley, except that in the Space Science Laboratory they were doing instrumentation, which wasn’t my thing. I didn’t have the aptitude for it . So I was just doing a theoretical stellar astrophysics problem and it took a while for me to really get going because I had a lot of Math Department requirements. They required that Ph.D. students pass two language exams, in addition to a preliminary math exam and a qualifying exam on topics of choice within math. I came to grad school knowing one language. I took French classes for many years prior to college, and I lived in a French-speaking dormitory when I was an undergrad, but I didn’t have another language. I had the choice of Russian or German and I didn’t feel like learning another alphabet so I chose German. This is really an aside but it took a while for me to get started seriously on my thesis work. My thesis advisor had a few other students and he was friends with Dave Black (then a CS at Ames), and Ames had some of these NASA graduate fellowships available. My advisor had funding for my project, but there was another student of his who was unfunded and wasn’t far along, so that student went to visit Ames and Frank said to me “you might as well go down too because you can meet some planetary people”.

And I did visit Ames and met a few people, including Pat Cassen and Jim Pollack, and we had some very pleasant discussions. And the next day when I was back on campus I got a call from someone who I hadn’t met, a Jeff Cuzzi, who said, “Hey, I’ve got a project for you: spiral density waves in Saturn’s rings.” Voyager’s going to go by Saturn soon and get some great data and I’m on the Voyager team working on rings. There was this theory on spiral density waves being important and my thesis advisor had done work on spiral density waves, he was a pioneer in the field, and I was interested in mathematical things, so it seemed like a great fit to Jeff. My advisor was not that interested but had another idea, thinking that because Jeff Cuzzi had done a problem more closely aligned with the problem that Frank Shu was interested in having me start on, to convince him to do this other problem with us, but Jeff was the convincing one,

My formal mathematics thesis advisor was a nice guy, very bright and helpful, but he didn’t really give me very much scientific advice, because my project was so far from his expertise. Frank Shu was my primary thesis advisor and Jeff Cuzzi was my secondary advisor, Frank on the theory and Jeff on the data. So I started coming to Ames regularly, maybe once a month, from Berkeley, sometimes with Frank and sometimes without, during my thesis. That was my first connection with Ames and the first work I did in planetary science.

How did you eventually come to Ames as an employee? Did you come as a civil servant or as a contractor or NPP?

This was a very circuitous path. I graduated and then I took a postdoc, the postdoctoral program was run through the National Research Council (NRC) back then so they were called NRC postdocs. I started in January and at the end Jeff had some money, he sent it to Berkeley, as the NRC program didn’t have a third year that grants could fund, or at least people at Ames didn’t know about it in that era.

So I was paid through Berkeley and worked another six months at Ames. Then I went to a second postdoc at U.C. Santa Barbara with Stan Peale, and after that started a faculty position at State University of New York at Stony Brook. I was at Stony Brook from start to finish nine years, although I wasn’t there all the time. The two professors who were in planetary, in the astronomy group there, who really brought me there, both left within the first few years for personal reasons. And I was not that happy there. So I was looking around and was getting interviews, but not very many because there were very few jobs back then, and planetary was not at all popular at universities. And it wasn’t that I just wanted any place, I wanted a place that I really liked in terms of combination of job and where to live. And I eventually got a position at Ames. I did come in as a civil servant, I was leaving a tenured faculty position. It was a career conditional, but it was pretty much standard that everybody got converted after a year unless something really bad happened. Not first as a contractor not even first as a term, which has gotten more common.

So in terms of the work that you actually do, have you been affected by the pandemic? Are you able to work pretty much 100% remotely, or is there a lab component or some other reason that you need to be on site? What is the typical day like for you at work?

I was not prepared to immediately go to 100% telework, in part because I had a cold a few days before Ames shut down and because COVID was ramping up, one did not go in with a cold or if you didn’t know what it was. I had no indication that it was COVID, I thought it was a regular cold because it was very mild.

It was difficult for the first few months because I didn’t have my primary computer and I didn’t have a good ergonomic set up. I finally got into my office to get my computer and a few other things in late May 2020, and since then I would say I’m able to work at 90% productivity.

You are one of the fortunate ones then.

Yes, yes. I’ve been in about a half dozen times (during the first two years of the pandemic), to get books and things from my office, and going into phase 2, as we start opening up, my request was a very modest one: to get once a month access on Sundays, because I want to be able to access my library. Even before the pandemic, a lot of my interactions with my local colleagues would be outdoor walking meetings where we would talk science. I did several of these during the relatively safe period just after we got our primary series of vaccinations, and a few at other times. But I miss having more of those meetings.

A lot of your colleagues have expressed that they miss that. In terms of your day-to-day work either before or during the pandemic, probably before because you’ve been there a while, what do you like best and least about your job as a NASA astrophysicist?

OK: I will state that the quality of my job as a NASA astrophysicist has varied substantially over the years I’ve been here. When I came, it was because of the group of people at Ames, a great planetary group, plus access to people elsewhere in the Bay Area and because it was in the Bay Area. As for the difference between being a university professor and an Ames civil servant, there were advantages and disadvantages. Thus, in two respects it was clearly better and in the third not obvious.

For about the first 6 ½-7 years I was at Ames it was significantly better than a faculty position, and then when we went to full cost recovery, which goes under the name of full cost accounting, but is not at all. You can’t do full cost accounting and full cost recovery while guaranteeing civil servant researchers full support.

You’re preaching to the choir about full cost accounting. I’m very familiar with it and it’s deficiencies and failures, really. We went through a painful time as you know. But go ahead.

I like the principle of full cost accounting, if we actually were doing that and writing what we were doing with our time, then NASA would have a more accurate accounting of CS scientists’ time and we would be doing what Congress intended, rather than wasting our time and the community’s time with excess proposals for salary that we were going to get anyway. So for 18 months there was a steep down slope in the quality of the job. And then it hit bottom and started getting better, although it was a much more gradual upslope and never got to as good as it was before.

It never got to where it needs to be, I understand that.

Yes, you understand this better than I do.

So here’s a question off the wall: you are currently a NASA astrophysicist, but if you weren’t what would your dream job be?

Faculty.

OK, that sounds good.

So there’s another thing: Stony Brook is a Research 1 (R1) University, and above average for Research 1 universities. But in astronomy we were not in the top 10. We were in the top 25, I think, but not in the top 10. So, well above average but we weren’t getting the very best students and the job market was so bad that you didn’t really want to train that many people who weren’t going be able to get good jobs. What we ended up doing, because we knew this, and we didn’t want to take mediocre students, so we took students who were, let’s put it this way: who had mixed records. There were uncertainties but there was potential for them to be really good. The ones who weren’t left after two years with a master’s degree, generally. But that made for a not very pleasant department environment.

And indeed, I didn’t know this when enrolled in grad school at Berkeley, but the Math Department was admitting ~ 75% of people who applied, and less than 30% who came in got Ph.D.’s. So I recognized that from that point of view it was just not a pleasant environment and I didn’t want to get large numbers of students because my area of planetary science was not a lucrative field, because it was mostly theoretical.

That is certainly understandable.

Let me add some things about this. When I was at Stony Brook there was no really good textbook, for either graduate students or for advanced undergrads, in planetary science. And in the course I had taken for advanced undergrads at MIT, the professor said “we thought about writing a book but we’d have to make it in loose leaf form because things are changing so much”. At Berkeley I became a TA and was able to teach a course in math, lecture it over the summer, but it was a preset curriculum. Astronomy had a really neat option where graduate students could teach small classes in specified areas that were kind of second classes for people who just had one Quarter of astronomy. And I taught a course using my notes from undergrad and developing them, and when I became a professor I decided I really wanted to write a textbook.

And at a conference, a DPS meeting (Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society), I was chatting with Imke de Pater, who was a planetary scientist hired at Berkeley a little after I left. She was hired despite her interest in planets because she was an excellent radio astronomer and they thought she would run out of planets and do something more interesting, but she has made a great career in astronomy at Berkeley, in planetary entirely. We had complementary expertise and decided to co-author a book. And we talked about this at conferences and started organizing our notes in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

By the time I came to Ames in ’96, Imke and I had drafts of a textbook, most of it. So I got permission for outside employment, because this was not part of my government work but it was related to science. I learned about government bureaucracy and government lawyers, some of whom seem to have the vocabulary of two-year-olds: No! No! No! No! No! (laughs) It took over a year, but I got an exemption, signed by the Center Director, to get this permission. I’ve gotten it renewed over time, although right now I’m not actively working on the book, and It’s expired because each approval lasts just three years. But I’m going to go back to that again. Anyway, I decided I wanted to teach with it. I had a friend who had an adjunct appointment at Stanford and an endowed chair at SETI Institute. And I went over to campus to see the Geo department because Stanford, especially the astronomy, the physics department, didn’t want anything to do with planetary. He introduced me to people there and there were things going on, so this was obviously the place to check in if I was going to be teaching.

Setting aside your professional career, what do you do for fun?

What do I do for fun? During the pandemic or before?

Before the pandemic is fine. We can broaden that later to include more current things, such as your hobbies, talents, sports, and so forth.

Actually in sports I have talent in one sport pretty much: softball. I was playing regularly through the 2019 season and would’ve been playing in 2020 and 2021 were it not for the pandemic. I am still a very good pitcher and an above average hitter!

Were you on Charlie Sobeck’s team?

I was on Charlie Sobeck’s team.

He was big into that, too.

Oh yeah! Actually, when I was here as a postdoc, I looked around for teams and there were two teams in the Space Science Division, but they were snooty, they didn’t want other people. So we (Marion Legg and I) put together a team that we called the Dregs. We had some good players and during our first season we played twice against the team that was really the snooty one, and we beat them the second time! They were just totally shocked, since the league was much more competitive at that time.

I played softball most years. I played intramurals in college, including most of my time at Berkeley. I played intramurals at Stony Brook, and I played many seasons on the Dregs, which I reconstituted when I came back because it had eventually petered out, but there just weren’t enough people, so I merged our team with Charlie’s team, the Space Cadets. The Dregs came to life again briefly, when Bob Haberle revived it to boost branch commeraderie, and when the Dregs were around I pretty much played with them, since I had loyalties to both teams and the Dregs needed a pitcher, whereas for the Space Cadets I shared pitching duties with Charlie. Other things I like to do include travel, hiking, food, both cooking and restaurants, and museums.

I wanted to ask you if you’d like to share anything about your family? Married? Kids? Pets? Anything like that?

I’ve been with the same woman for the better part of a decade now, and we have spent a lot of time together, especially during the pandemic. We are very isolated right now from people due to the omicron surge, as was the situation during the first year of course, too. We do have a cat who owns us. Saying that we own a cat is not appropriate (laughs). This cat was obviously a Pharoah in a previous life, and still has that attitude.

They don’t grow out of that much do they?

No, no. Not even after many reincarnations!

Would you like to share some additional experiences and accomplishments from your career?

Since I’ve been working as a Civil Servant at Ames, I’ve done several science-related art projects in collaboration with artists and graphic designers. Two of these began with my work. In the late 90’s, I was interviewed for an article on planet formation being written for a popular scientific magazine. The cover for that issue was being had been commissioned from space artist Lynette Cook and the magazine asked me to serve as a scientific consultant for the artwork. I liked the final product, https://sciencephotogallery.com/featured/alien-planet-forming-lynette-cookscience-photo-library.html, so much that I purchased the original painting for my personal collection and our textbook publisher acquired the rights for use of the image on the cover of my graduate-level text mentioned earlier.

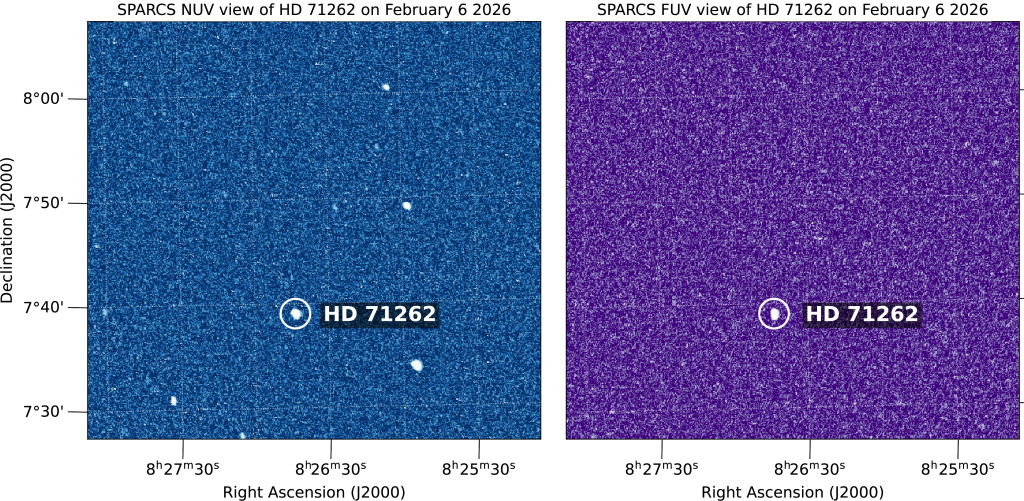

As part of my work as Co-Investigator on the Kepler mission, I led the analysis of a candidate multi-transiting planetary system that we were able to verify and characterize, which became known as Kepler-11. After the paper was submitted for publication, I worked, together with a few of my co-authors to design, and consulted with graphic artists paid for by the mission on the production of, a representation of the Kepler-11 planetary system that was used for the cover of the issue of Nature magazine in which the discovery paper appeared (another version of this graphic that was released as part of the NASA press conference announcing the discovery, https://www.nasa.gov/images/content/511895main_Kepler-11_IntroShot_full.jpg). Almost all representations of exoplanets seen by the public are science fiction, usually mostly fiction, but my co-authors and I wanted ours to have more scientific content. The final product shows three of the six known planets transiting their star and each of the other three planets on either side of the stellar disk. The radii of the planetary disks are proportional to the radii of the actual planets, the positions of the three planets in transit correspond with those of the actual transiting planets at a particular epoch that had been observed. However, the other three planets are moved much closer to the star than they were at that time and all of the planetary radii are enlarged relative to that of the star by a factor of almost three, in both cases to improve the appearance of the figure and facilitate the communication of scientific information. The host star is sunlike, so a photo of the Sun was used to represent it, but the selected photo shows the Sun with an exceptionally large number of sunspots, because it is more asthetically interesting.

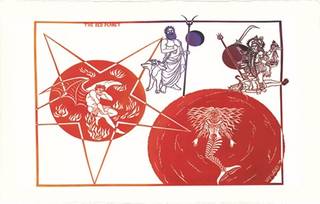

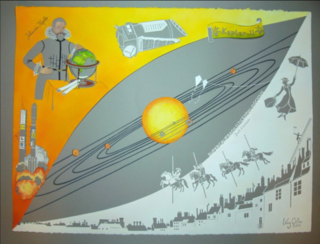

By far the my most substantial and longest-lasting artistic collaboration started with my interest in art, back in 1998. I went to an opening reception for a show of works by local emerging artists in San Francisco, and I was so taken by a shadowbox-framed papercut entitled ‘The World’, which was multicultural and had many interesting historical and literary references, that I decided to purchase it then and there. Because the show was just starting, I couldn’t take the piece with me, but had to return to pick it up at a later date. The artist, Kay Weber http://kayweberartstudio.com, who wasn’t at the reception, offered to meet me at the gallery and explain all of the aspects of the piece when I returned there to pick it up. Our meeting lasted more than an hour, during which he pointed me to many detailed aspects of the piece, explaining the sources and cultural connections. We got along very well, and either during this meeting or soon thereafter, I commissioned him to make a companion papercut entitled ‘The Solar System’, which shows the Sun, planets and some other bodies, representing them using themes from the Roman dieties. We designed the piece together, with me focusing on the science and Kay on the mythological themes and specifics of the layout. For example, I decided that the best compromise between scientific accuracy and asthetic appeal was to have the radii of the Sun and planets proportional to the square root of the bodies’ radii. Kay and I have done a few subsequent collaborative science-related art projects together, including two depicting exoplanetary systems that I had a role in discovering (Gliese 876 and the aforementioned Kepler-11), as well as a multi-layered piece called ‘Creation’ that showed the biblical and Greco-Roman mythological versions, with a representation of the cooling and expanding universe in the background. Mark Showalter, a planetary rings and small moons researcher who worked at Ames for two decades, also was very impressed by Kay’s art and commissioned Kay to make a papercut on the rings and small inner moons of Uranus, including the two moons and two rings that Mark and I had jointly discovered.