The NACA

As we celebrate the 110th anniversary of the March 3, 1915 formation of NASA’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, we take a deeper look at the contributions of the four research centers where it all began.

It shall be the duty of the advisory committee for aeronautics to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution.

congressional direction in establishing the NACA in 1915

Chapter 1

PRELUDE

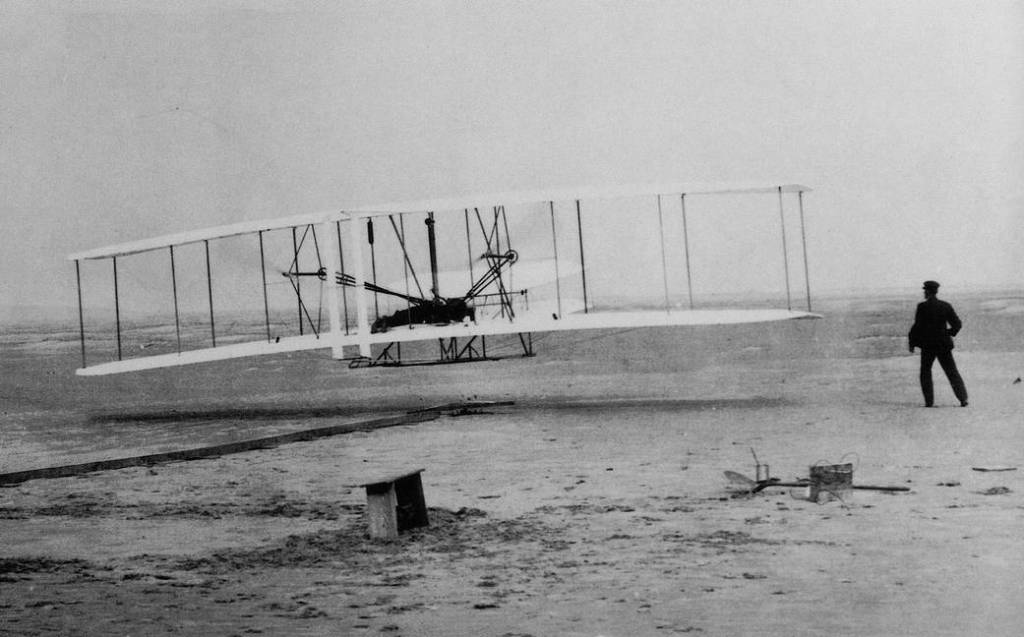

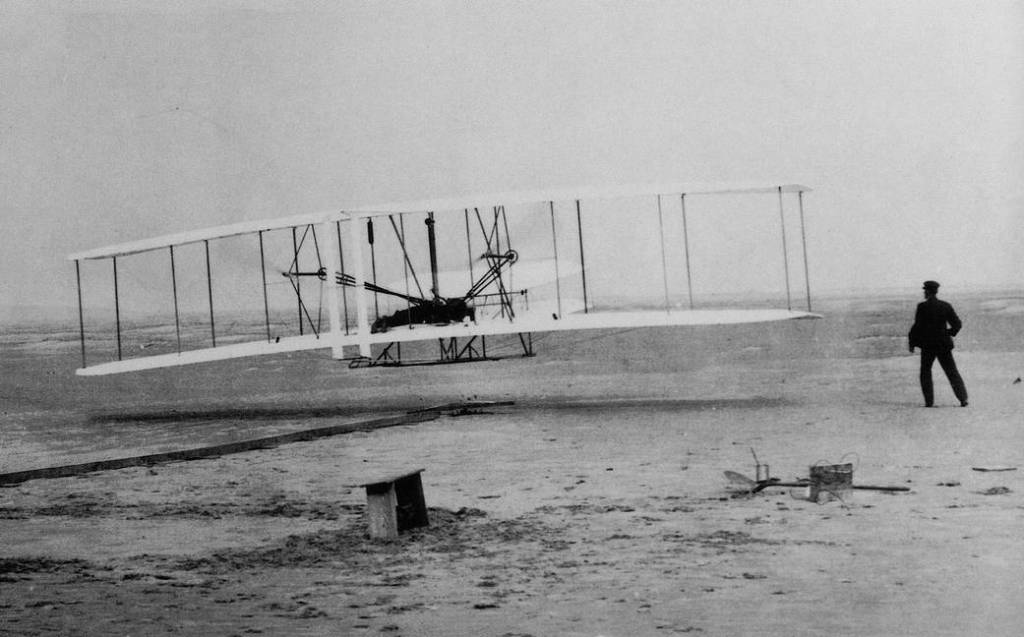

The Wright Brothers made history with their 1903 flight, but U.S. leadership in aviation during the next decade fell behind as Europe invested in aeronautical research before the first world war.

The U.S. Answers with the NACA

The U.S. responded to Europe’s aeronautical trailblazing in 1915 by forming a committee of government, military, and industry leaders. It was called the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or the NACA — with each letter pronounced.

The NACA contributed to some of the most important advancements in the history of flight. And its people, its laboratories, and legacy, became the basis for NASA at the dawn of the Space Age.

Chapter 2

ORIGINS

NACA research at what is now Langley Research Center had a modest start with two hangars, an initial staff of eleven people, and a single wind tunnel whose design was obsolete by the time it began operations.

An Immediate Difference

Despite unassuming beginnings, NACA researchers wasted no time setting the gold standard for aeronautical innovations, many of which became the basis for aviation technologies still in use today.

One of the earliest advances was the NACA cowling, an aerodynamically efficient engine cover that improved aircraft performance, fuel efficiency, and safety. It made such a difference that in 1929 the technology and its inventors were awarded the Collier Trophy, aviation’s highest honor.

The Mother Center

Founded in 1917, Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory was the first established NACA facility. All other NACA research centers grew from Langley, giving it the nickname of the Mother Center.

Explore Today's Langley Research Center

Chapter 3

GROWTH

With an ever growing demand for advances in aviation to serve both military and civilian needs, the NACA had to grow as well and found just what it needed by locating its second aeronautics laboratory in what would become Silicon Valley near San Francisco.

Doing Things Big

The laid back West Coast culture didn’t keep researchers at Ames from making urgent, big strides in aviation during and after World War II with the help of what was then the world’s largest wind tunnel, which opened in 1944.

Achievements at Ames were many, with notable ones including design improvements to the P-51 Mustang fighter that helped win the war, and a Collier Award-winning method for preventing fatal ice build up on wings.

West Coast Expansion

Founded in 1939, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory gave the NACA room to establish new facilities and expanded research capabilities at a time when California's aviation industry was rapidly growing just before World War II.

Explore Today's Ames Research Center

Chapter 4

ENGINES

The desire for airplanes — and eventually rockets — to fly faster, higher, and farther meant the NACA needed new ideas and research capabilities for improving propulsion. The solutions would be found in a new engine laboratory set up in Ohio.

Moving Right Along

From the NACA’s engine laboratory’s start in 1941, each decade saw propulsion advancements that began with piston-driven propellers; continued on with turbojets, pure jets, and ramjets; and then moved on to rocket engines to power the Space Age.

The Power and the Glory

Founded in 1941, the NACA's Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory took the lead in studying all aspects of aircraft propulsion, increasing available power and enabling faster aircraft for both military and civilian uses.

Explore Today's Glenn Research Center

Chapter 5

AERONAUTICS

Above the deserts of Southern California, in 1947, the American rocket-powered X-1 experimental aircraft broke the sound barrier as a small team of NACA specialists monitored the flight below. A golden age of flight research had begun.

X Marks the Spot

From the X-1 in 1947 to the upcoming flights of the X-59 and X-66, experimental aircraft — X-planes — have been a staple of flight test operations at what is now Armstrong Flight Research Center. Work done by the NACA through 1958 and NASA ever since, not only with X-planes but research aircraft of all sorts, has advanced our understanding of all things aeronautics, making air travel one of the safest modes of transportation.

Pushing the Limits

Thirteen people from the NACA's Langley Laboratory arrived at Muroc Army Air Field in 1946 to support testing of a rocket plane that first flew faster than sound a year later. From that seed grew the flight research center NASA operates today.

Explore Today's Armstrong Flight Research Center

End of an Era and a New Beginning

From 1915 to 1958, the NACA led the world in aviation research. During this golden age of aeronautical innovation, air travel evolved from small wood and fabric airplanes flying a few hundred feet high to rocket-propelled aircraft built from exotic metals cruising to the edge of space. The commercial jet age was taking off and the promise of supersonic airliners was just beyond the horizon. When the Soviet Union shocked the world with Sputnik in 1957, the U.S. reacted by creating a new agency in 1958 to research and develop the technology required to win the “Space Race.” The nation looked to the experienced experts at the NACA to form the foundation of the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The NACA was no more, but its rich heritage of research excellence lives on today within NASA’s Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate.

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

With its elite research engineers and world-class test facilities, NASA’s predecessor, the NACA, was the nation’s premier aeronautical research institution for over 40 years.

Read this History Piece on the NACA

The NACA

About the Author

Jim Banke

Jim Banke is a veteran aviation and aerospace communicator with more than 40 years of experience as a writer, producer, consultant, and project manager based at Cape Canaveral, Florida. He is part of NASA Aeronautics' Strategic Communications Team and is Managing Editor for the Aeronautics topic on the NASA website.