With a sudden “crack!” of pyrotechnics, a mockup of NASA’s Orion spacecraft released its grip on a set of cables and began a graceful, deliberate dive toward a pool 14 feet below.

Instead of an Olympic-style feat of athletics, it was a mighty stroke of engineering — and an essential step forward in NASA’s journey to Mars.

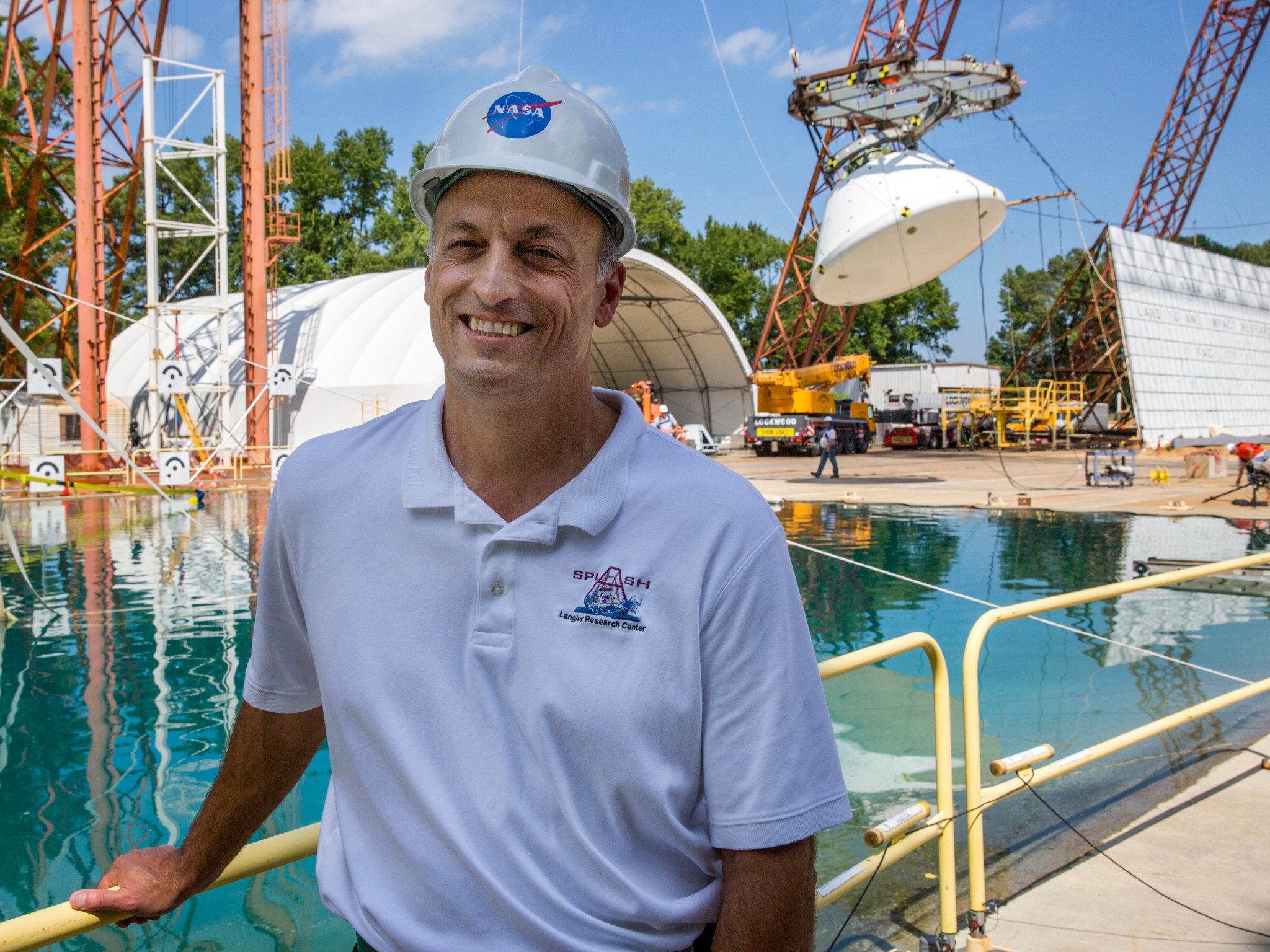

Onlookers gathered near the Hydro Impact Basin at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, applauded and cheered. They had just witnessed the simulated water landing of a space capsule, through the use of a 7.2-ton mockup covered with sensors capable of detecting forces that the structure and its astronaut crew would experience.

In that sense, spectators caught a glimpse of the future.

“We’re very proud of what we do here and we’re happy to be making this contribution to Orion,” said project chief engineer Jim Corliss. He explained that the forces that hit a spacecraft at splashdown determine the design of more than half of its structure. Understanding those forces is critical for astronaut safety.

“A water landing is not a trivial event at all,” Corliss said. “With these tests, we’re helping to protect the crew.”

Lara Kearney, manager of the Orion Crew and Service Module Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, traveled to Langley to watch Thursday’s test.

“Orion is a one-of-a kind spacecraft, and we’re testing it in a one-of-a kind facility,” she said. “Langley has a rich history in impact testing and the Hydro Impact Basin is a world-class facility that gives us the ability to control the specific impact conditions of interest with a high degree of accuracy.”

“Over the course of this test series, the test article and the facility have performed nearly flawlessly,” Kearney said. “I’m very proud of the team.”

Number nine

Thursday’s drop was the ninth in a series of 10 tests taking place at Langley’s Landing and Impact Research Facility. It was designed to simulate one of the Orion spacecraft’s most stressful landing scenarios, a case where one of the capsule’s three main parachutes fails to deploy. That would cause Orion to approach its planned water landing faster than normal and at an undesirable angle.

Under ideal conditions, the Orion capsule would slice into the water of the Pacific Ocean traveling about 17 miles per hour. Thursday’s test had it hitting the pool at about 20 mph, and in a lateral orientation. Instead of being pushed down into their seats, astronauts in this scenario would splashdown to the side.

“We’re looking at some of the hardest impacts, the ones that could potentially pose the most risk of injury to the crew or damaging the structure,” Corliss said. “That’s what we’ve been doing with these 10 tests.”

In the Apollo era, experiments like this one were commonplace. Today, the vast majority of NASA’s testing is done through digital simulations. However, computer models have some limitations.

“Because we rely so much on computer models now, we need at least some physical tests to anchor those models, to make sure they are accurate,” Corliss said.

High-fidelity data

With Thursday’s success and one final drop in this series scheduled for mid-September, researchers have accumulated a lot of important information.

For each test, they have captured data flowing in through about 535 channels. Each channel represent a sensor calibrated to measure the spacecraft’s behavior and condition as well as the experience of its inanimate crew of two heavily instrumented crash test dummies.

The sensors are capable of gathering 10.7 million pieces of high-fidelity data every second.

“We’re really ecstatic about the data we’re getting and encouraged with how well it’s correlating with our computer models,” Corliss said.

The drop tests are the culmination of a three-year collaborative effort among workers at five NASA facilities — Johnson Space Center, Kennedy Space Center, Marshall Space Flight Center, Ames Research Center and Langley — along with help from Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin.

Thousands of work hours have gone into each test, which is over in a matter of seconds.

On time, on target

Since testing began in April, the project has stockpiled 99 percent of its target data, and covered most of the splashdown scenarios originally mapped out.

One of that team’s biggest challenges was connecting the mock spacecraft — called the Ground Test Article in NASA language — with the heat shield used during Orion’s first flight, Exploration Flight Test-1, which took place in 2014.

Leaders realized that matching the heat shield with the mockup could make the tests more accurate and less expensive. But the two elements were not designed to fit together. Mating them required ingenuity.

First, NASA Marshall removed the remaining thermal protection covering, which was left over from re-entry. Then, the heat shield was shipped to Langley where extensive integration and sensor installation work took place.

“There’s so much satisfaction watching this test, knowing all the hard work that went into it,” Corliss said. “This test is complex. The fact that we were able to successfully conduct it, meet our impact conditions, and see it behave the way we expected it to, that’s a testament to the whole team.”

The tests at Langley — along with many others across the agency — are leading up to the first integrated flight of the Space Launch System and Orion known as Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1). For that, Orion will fly atop the Space Launch System, the most powerful rocket in the world. There will be no crew on EM-1, but it will prepare the way for future missions with astronauts as NASA pushes ahead on its journey to Mars.

- To see more photos from the Orion drop test, visit this Flickr gallery.