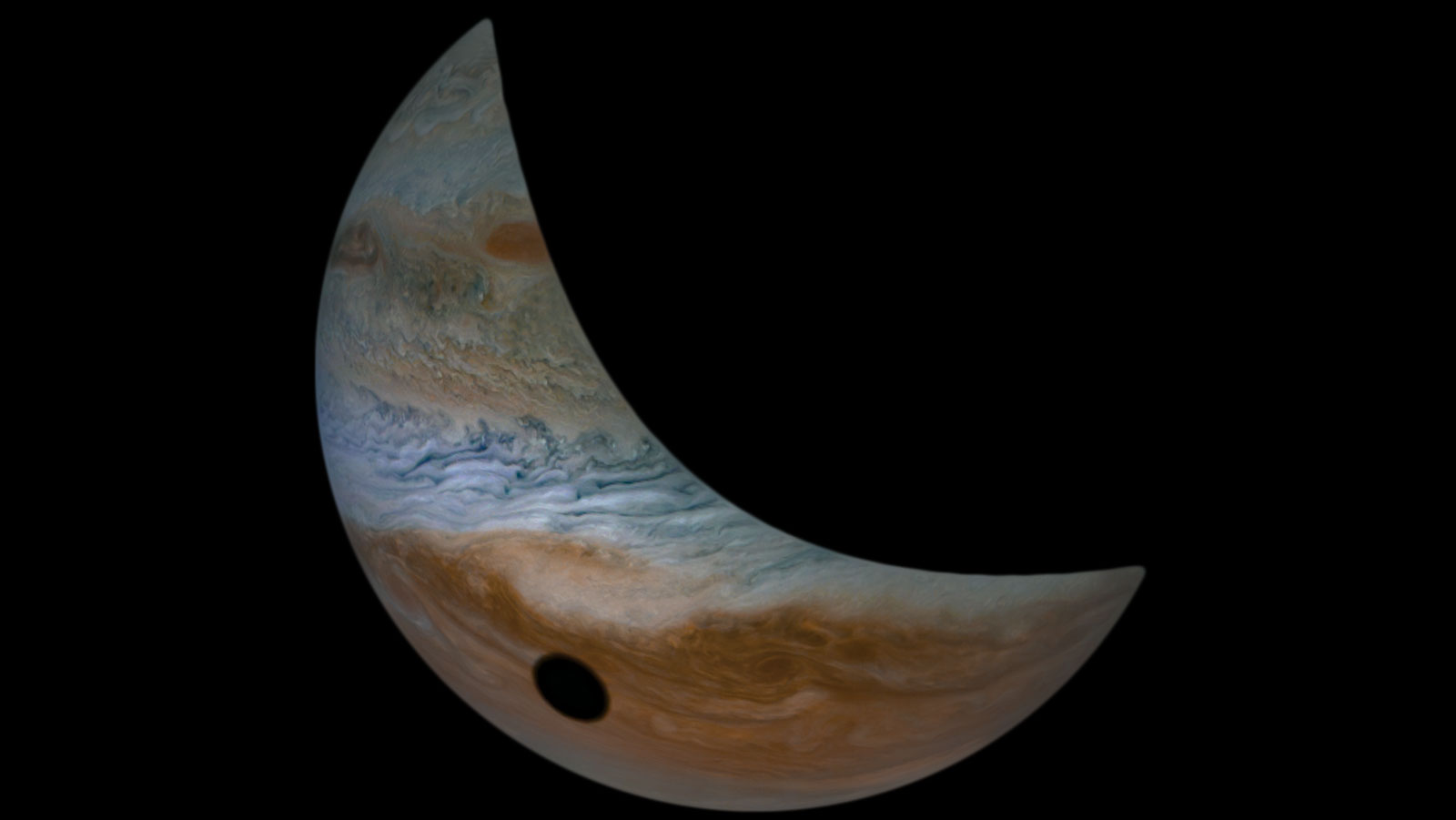

Jupiter’s south pole has a new cyclone. The discovery of the massive Jovian tempest occurred on Nov. 3, 2019, during the most recent data-gathering flyby of Jupiter by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. It was the 22nd flyby during which the solar-powered spacecraft collected science data on the gas giant, soaring only 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) above its cloud tops. The flyby also marked a victory for the mission team, whose innovative measures kept the solar-powered spacecraft clear of what could have been a mission-ending eclipse.

“The combination of creativity and analytical thinking has once again paid off big time for NASA,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “We realized that the orbit was going to carry Juno into Jupiter’s shadow, which could have grave consequences because we’re solar powered. No sunlight means no power, so there was real risk we might freeze to death. While the team was trying to figure out how to conserve energy and keep our core heated, the engineers came up with a completely new way out of the problem: Jump Jupiter’s shadow. It was nothing less than a navigation stroke of genius. Lo and behold, first thing out of the gate on the other side, we make another fundamental discovery.”

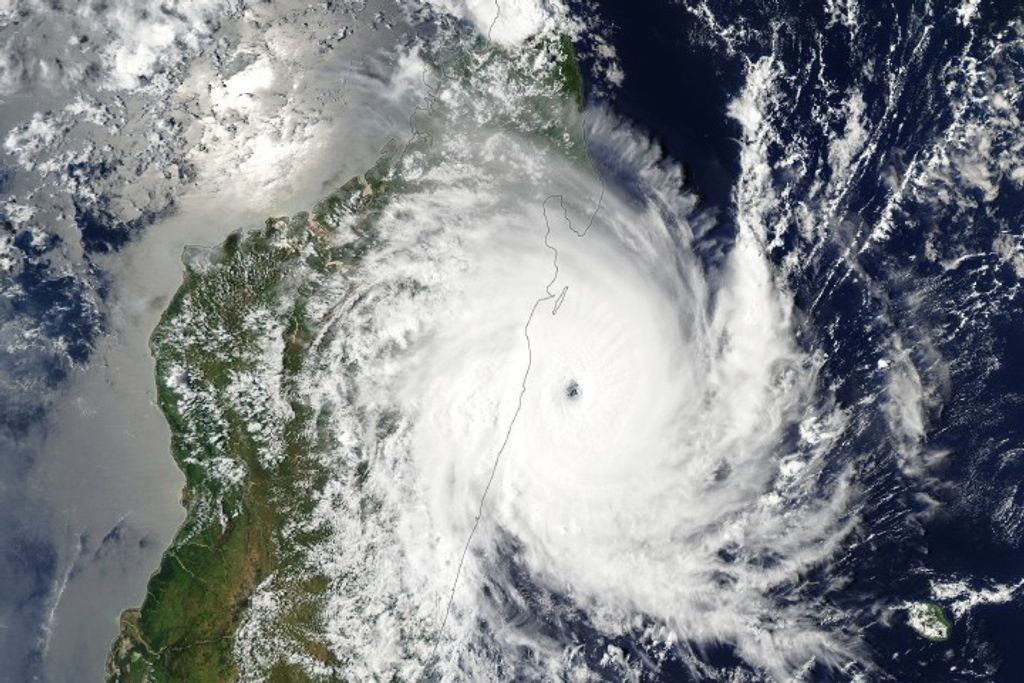

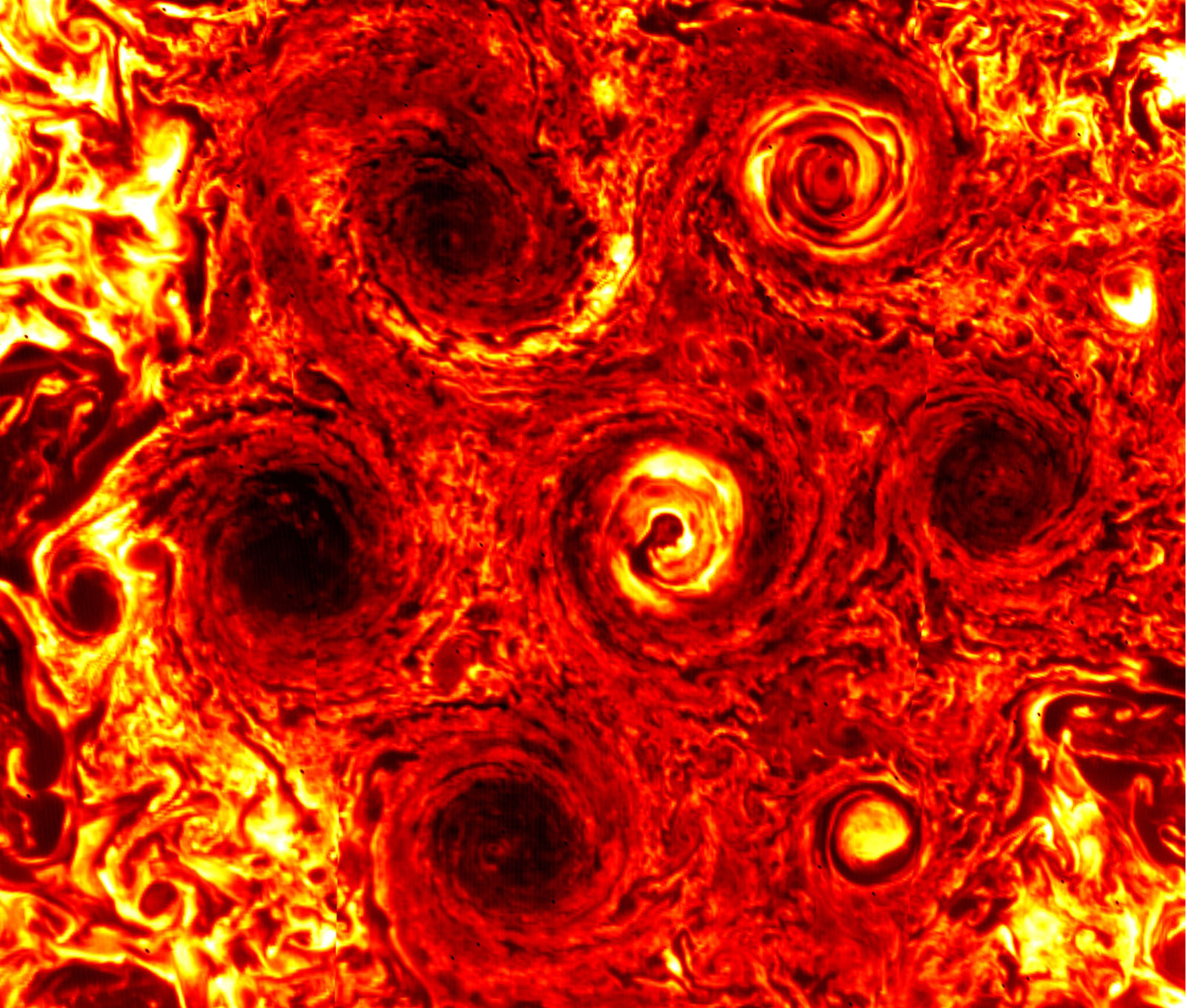

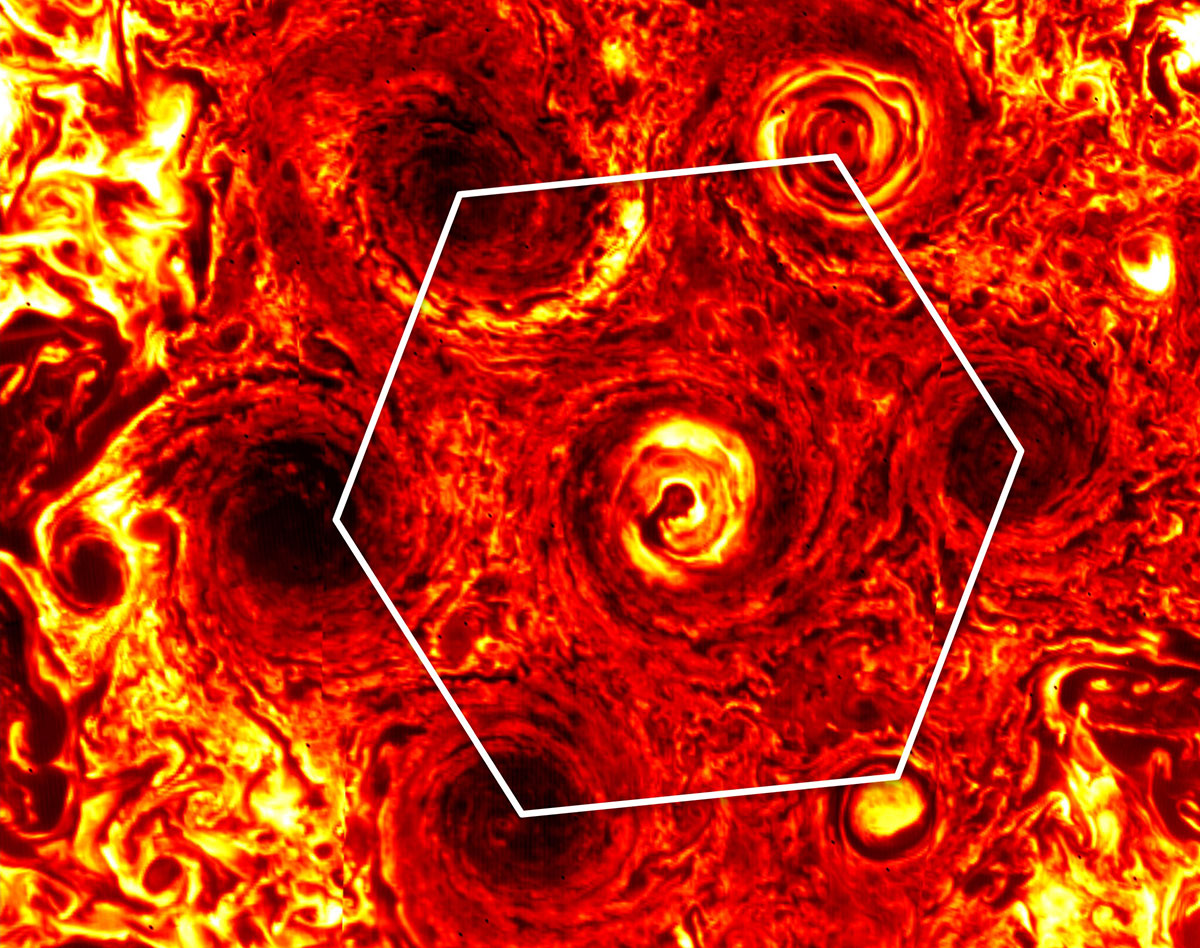

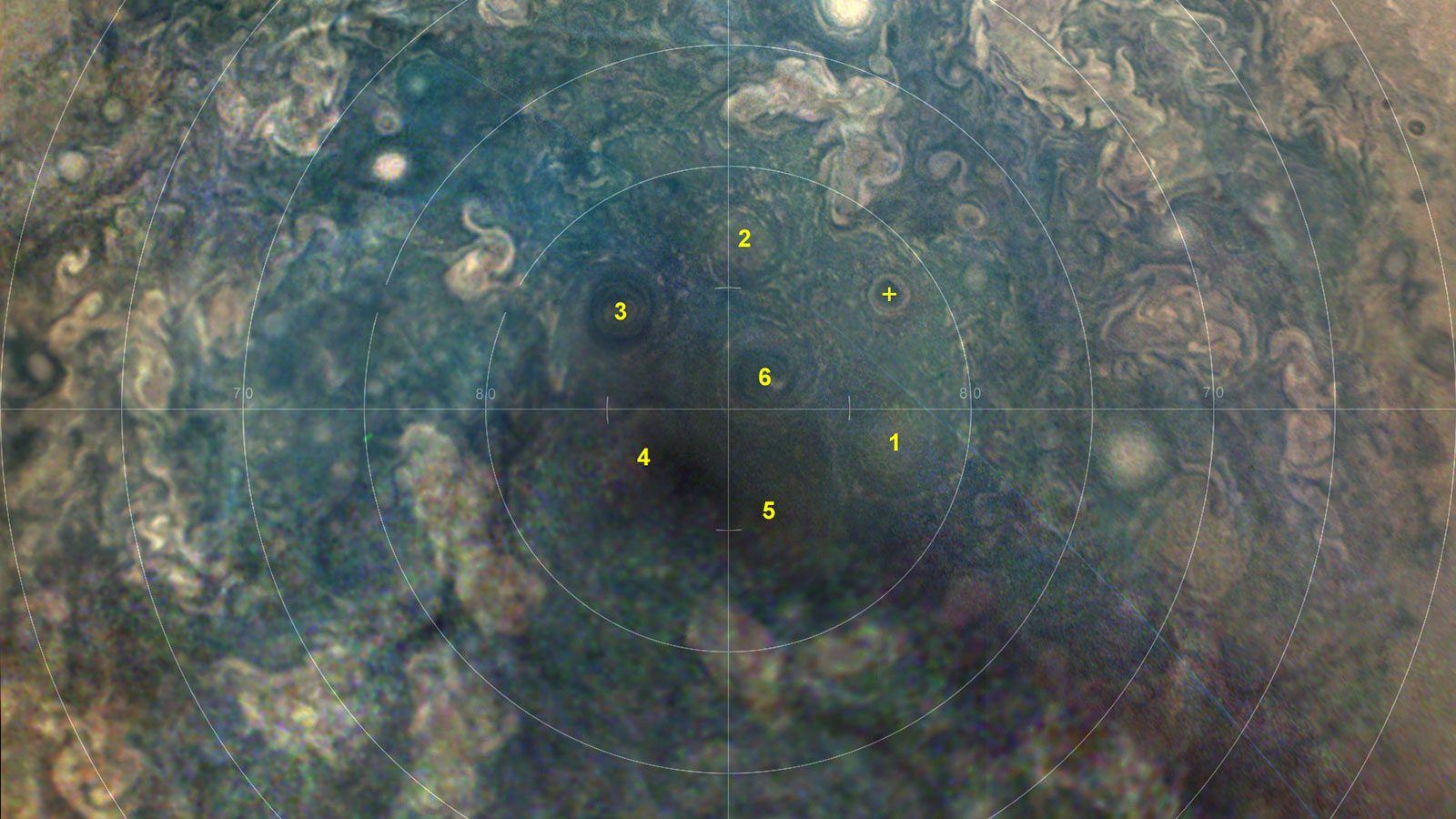

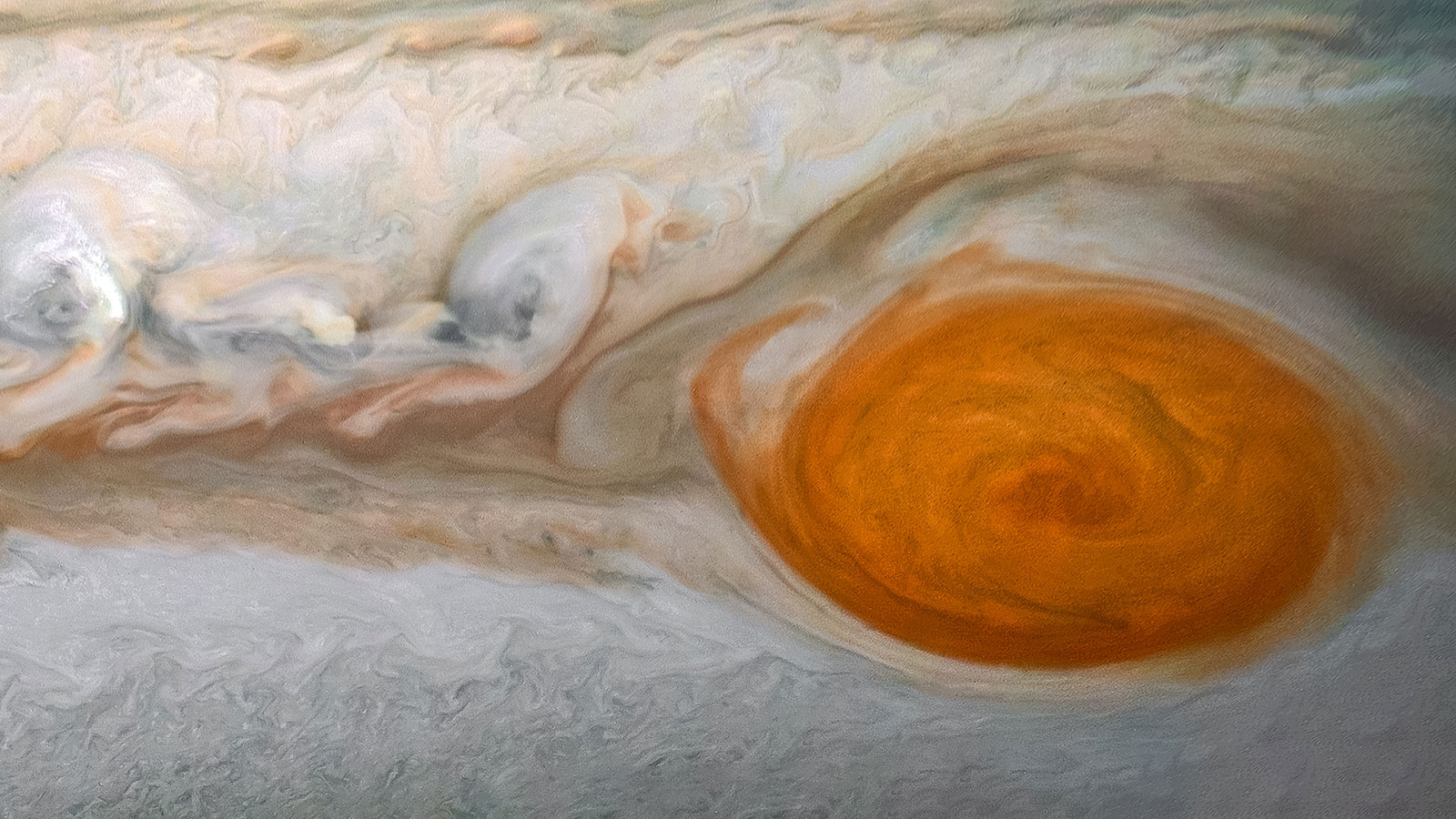

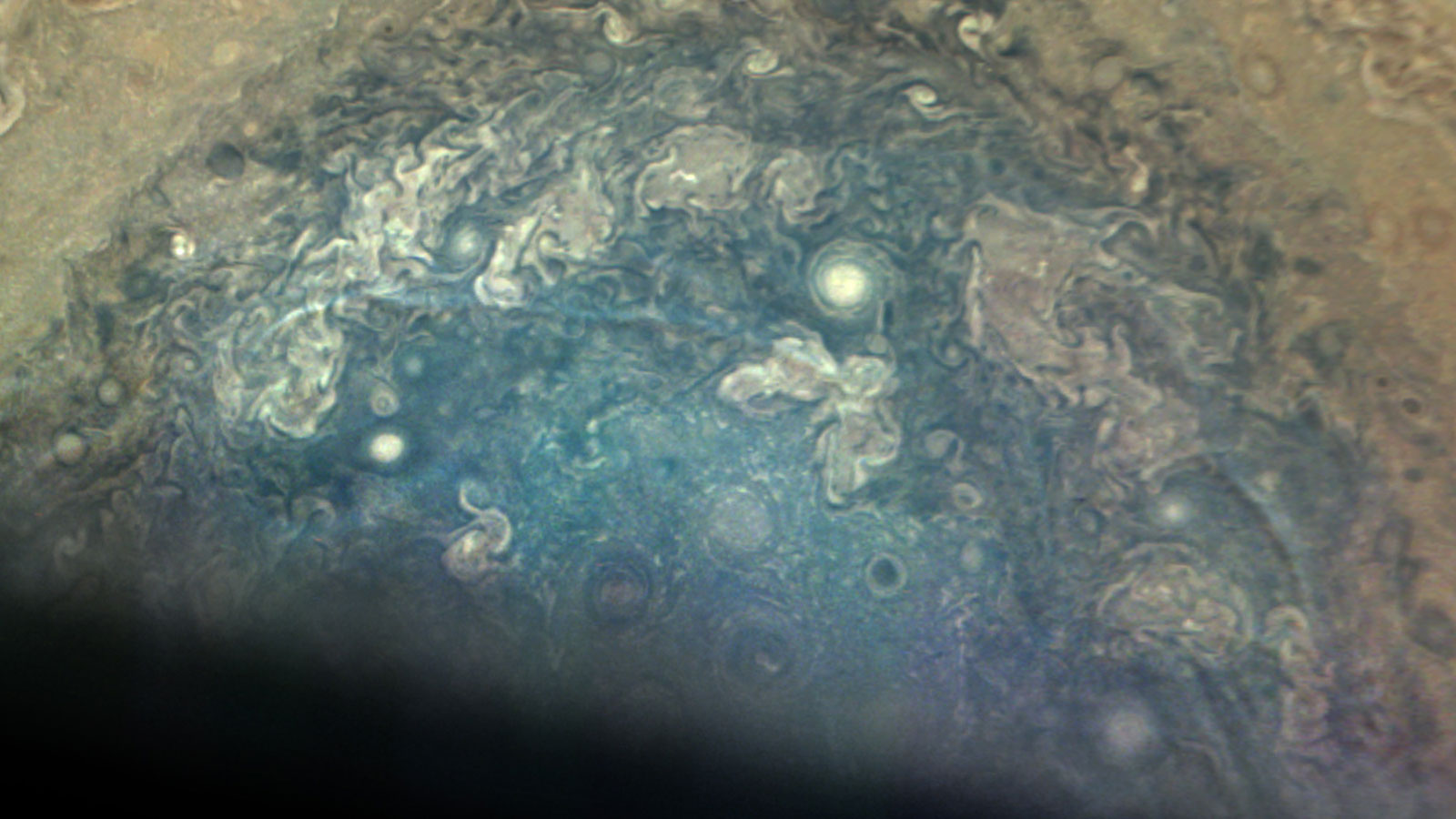

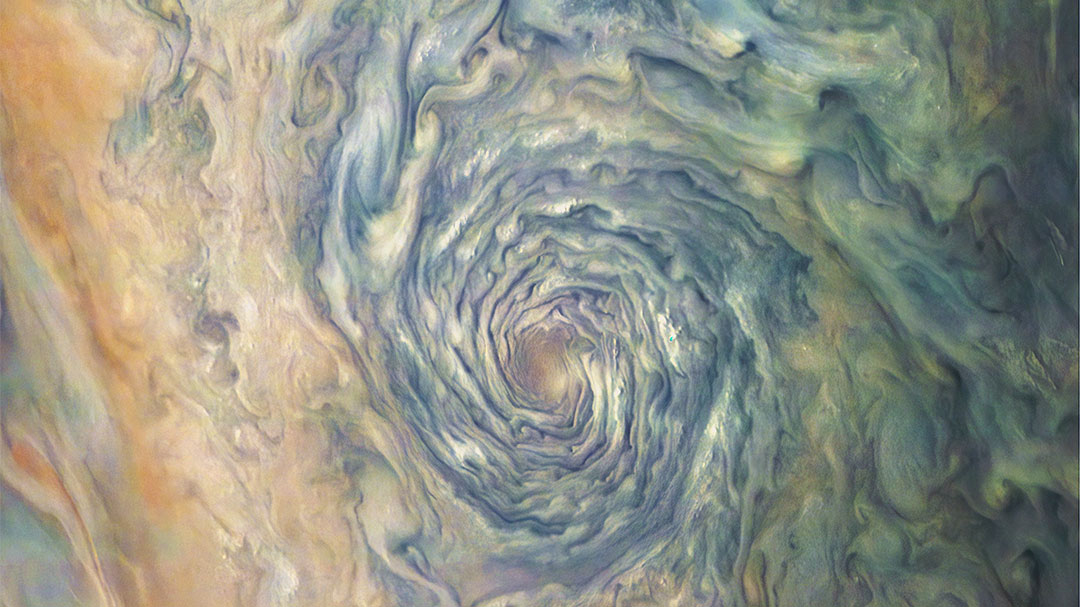

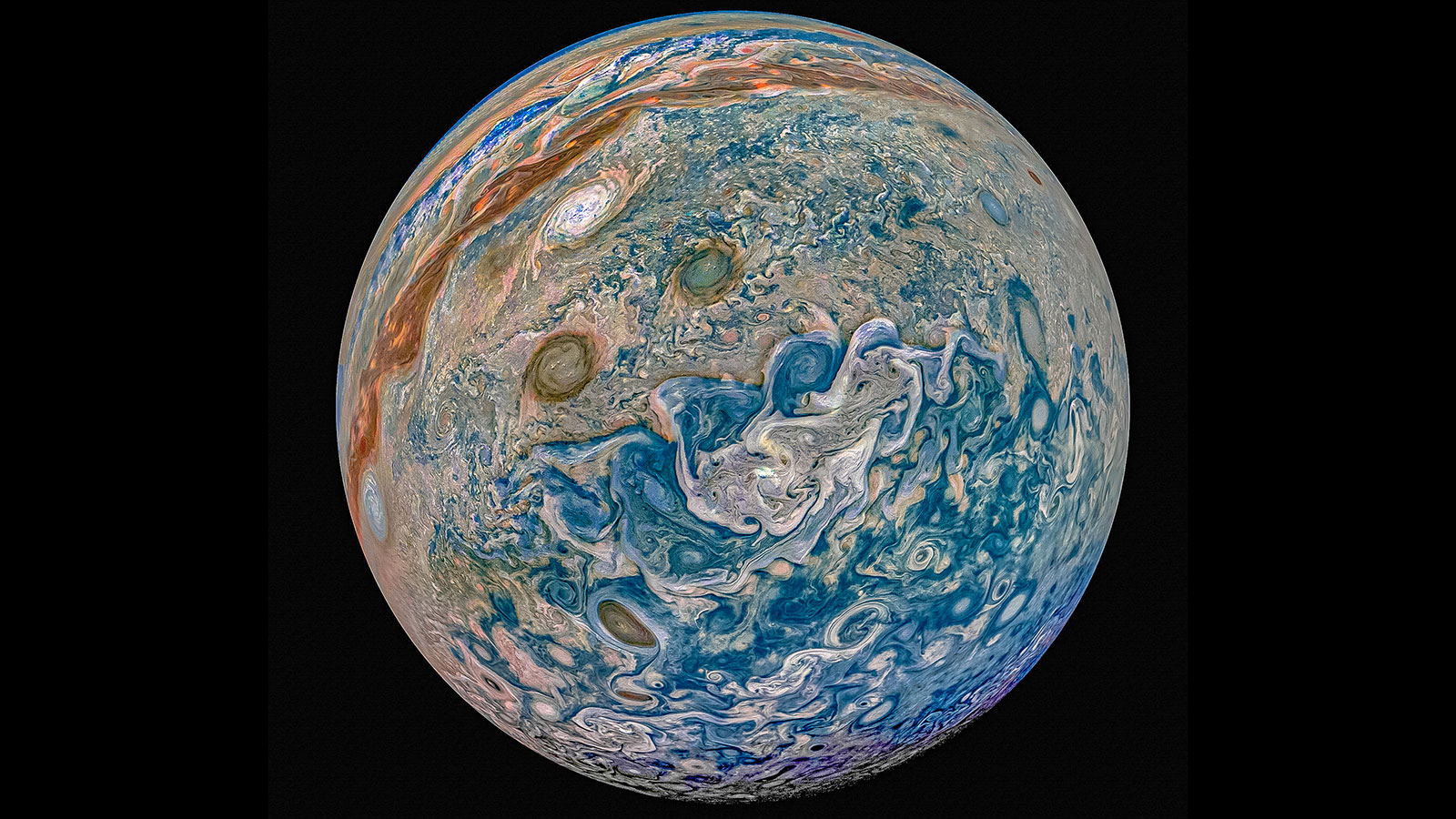

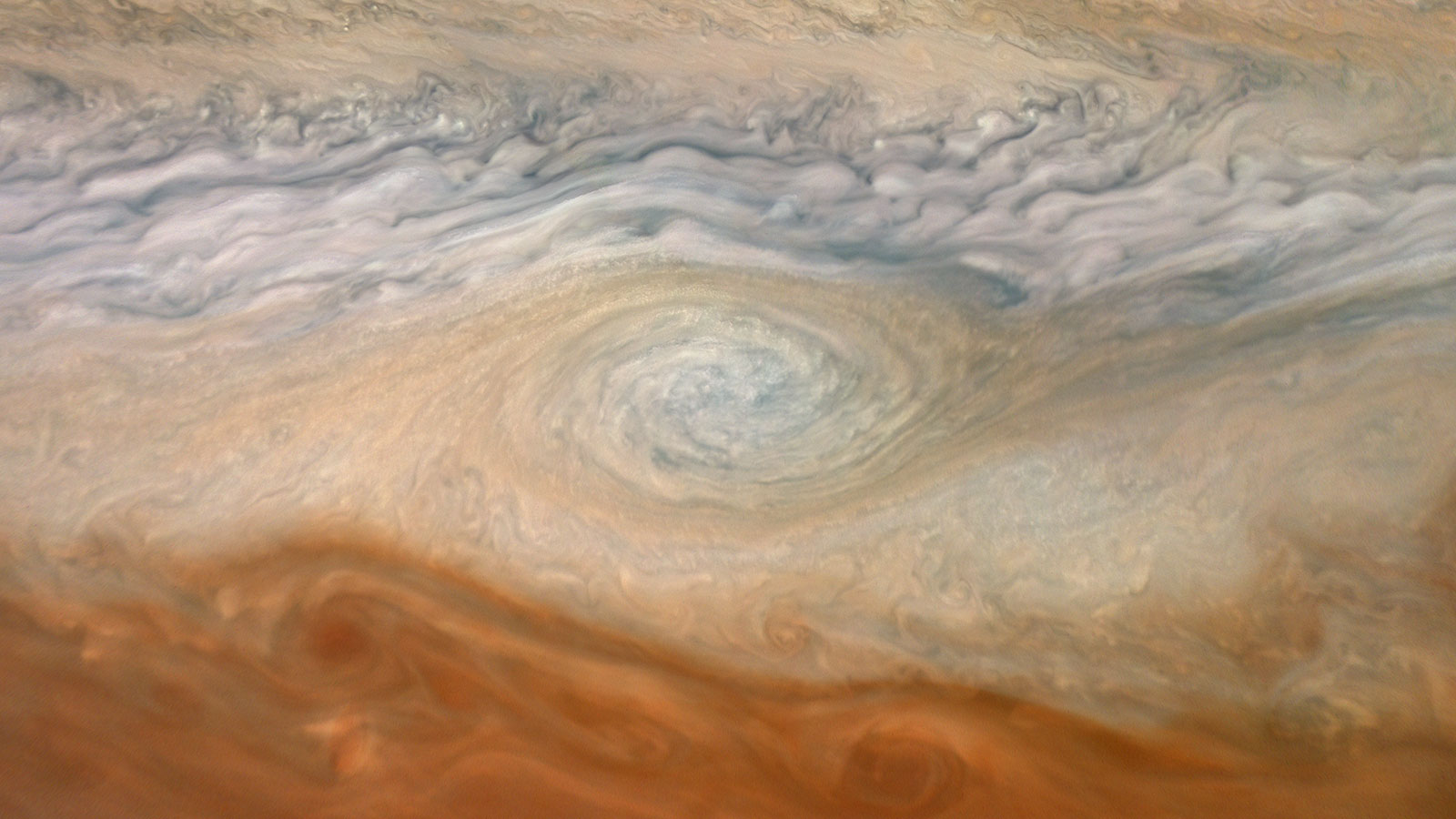

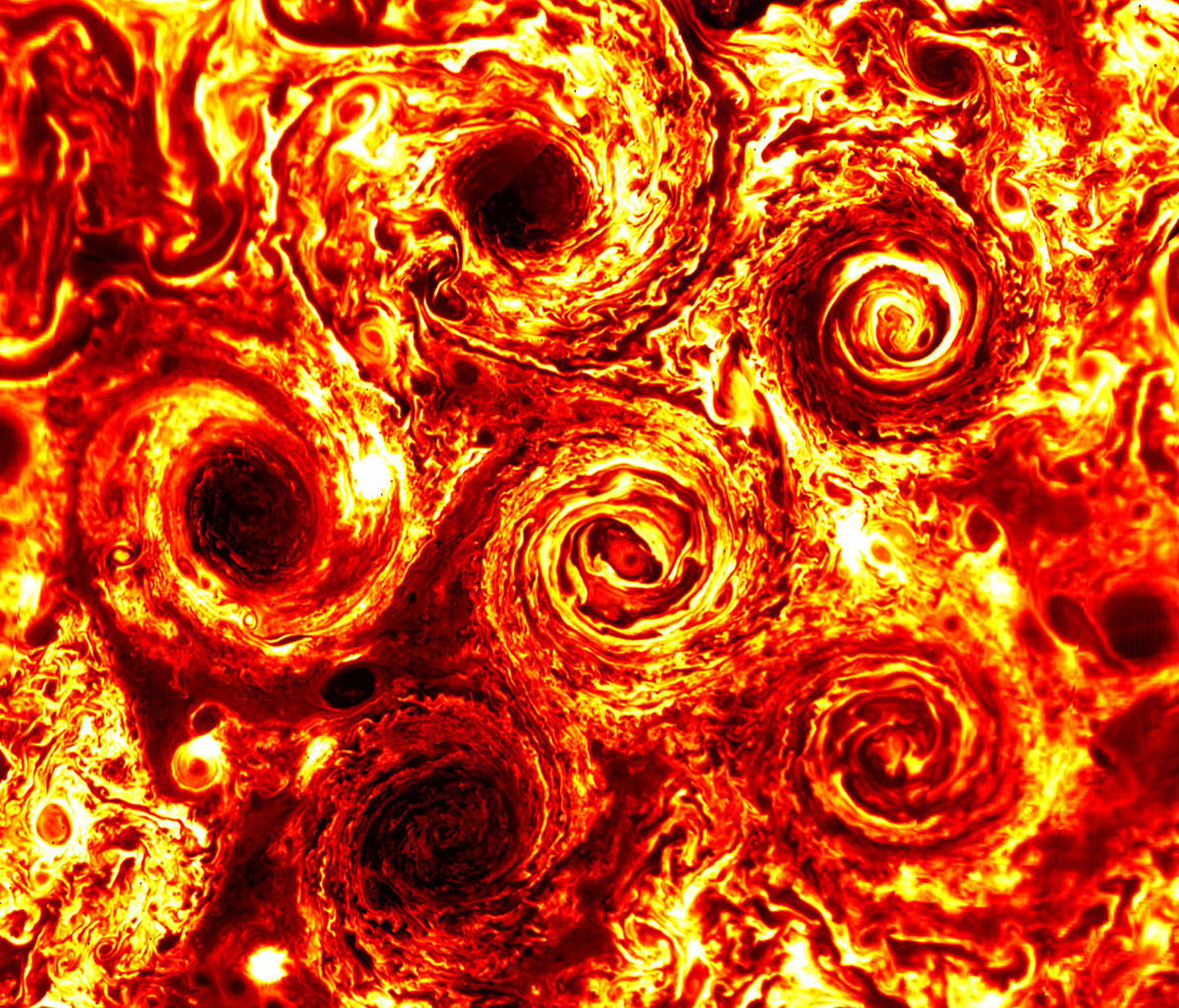

When Juno first arrived at Jupiter in July 2016, its infrared and visible-light cameras discovered giant cyclones encircling the planet’s poles — nine in the north and six in the south. Were they, like their Earthly siblings, a transient phenomenon, taking only weeks to develop and then ebb? Or could these cyclones, each nearly as wide as the continental U.S., be more permanent fixtures?

With each flyby, the data reinforced the idea that five windstorms were swirling in a pentagonal pattern around a central storm at the south pole and that the system seemed stable. None of the six storms showed signs of yielding to allow other cyclones to join in.

“It almost appeared like the polar cyclones were part of a private club that seemed to resist new members,” said Bolton.

Then, during Juno’s 22nd science pass, a new, smaller cyclone churned to life and joined the fray.

The Life of a Young Cyclone

“Data from Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper [JIRAM] instrument indicates we went from a pentagon of cyclones surrounding one at the center to a hexagonal arrangement,” said Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome. “This new addition is smaller in stature than its six more established cyclonic brothers: It’s about the size of Texas. Maybe JIRAM data from future flybys will show the cyclone growing to the same size as its neighbors.”

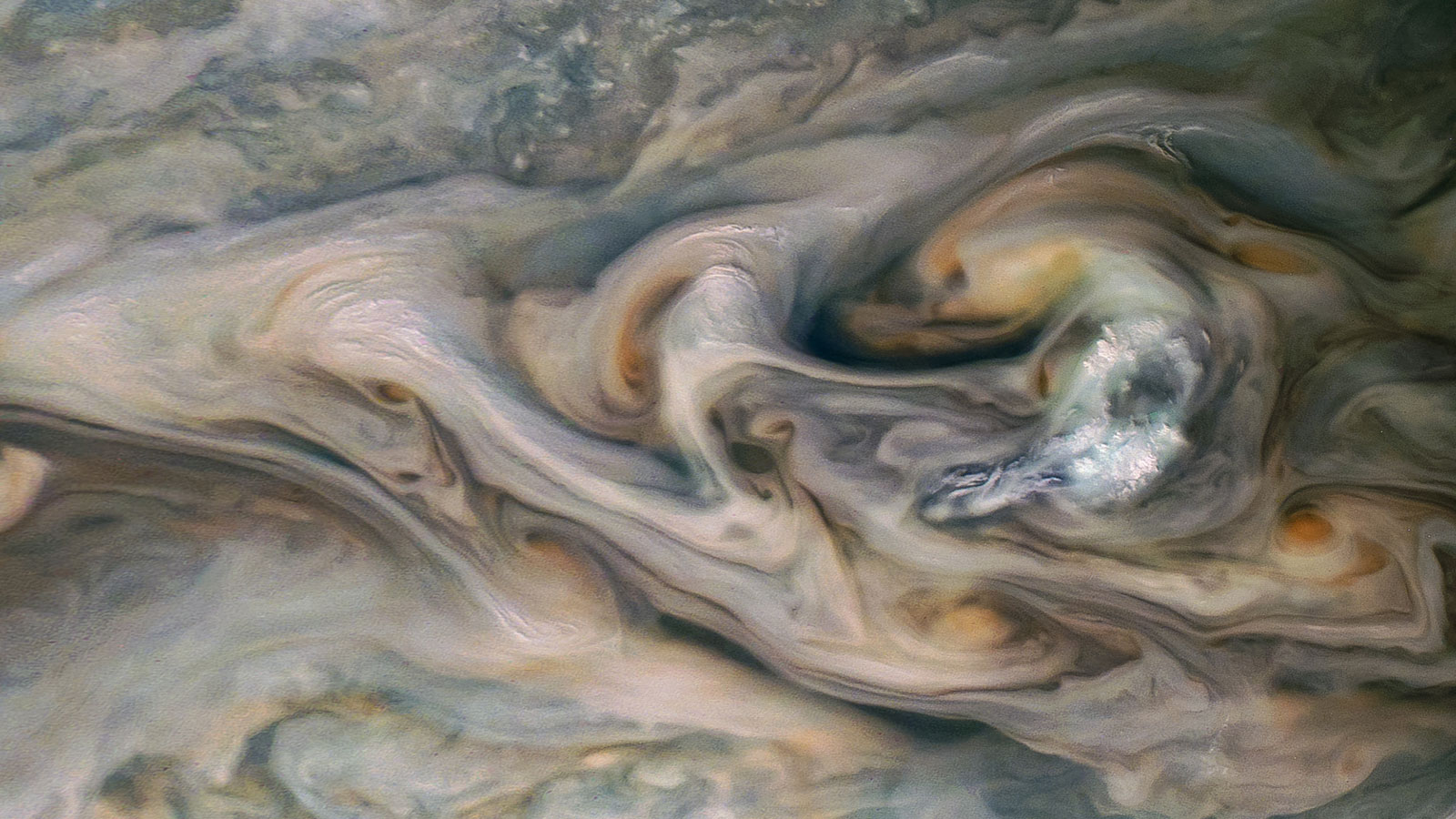

Probing the weather layer down to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) below Jupiter’s cloud tops, JIRAM captures infrared light emerging from deep inside Jupiter. Its data indicate wind speeds of the new cyclone average 225 mph (362 kph) — comparable to the velocity found in its six more established polar colleagues.

The spacecraft’s JunoCam also obtained visible-light imagery of the new cyclone. The two datasets shed light on atmospheric processes of not just Jupiter but also fellow gas giants Saturn, Uranus and Neptune as well as those of giant exoplanets now being discovered; they even shed light on atmospheric processes of Earth’s cyclones.

“These cyclones are new weather phenomena that have not been seen or predicted before,” said Cheng Li, a Juno scientist from the University of California, Berkeley. “Nature is revealing new physics regarding fluid motions and how giant planet atmospheres work. We are beginning to grasp it through observations and computer simulations. Future Juno flybys will help us further refine our understanding by revealing how the cyclones evolve over time.”

Shadow Jumping

Of course, the new cyclone would never have been discovered if Juno had frozen to death during the eclipse when Jupiter got between the spacecraft and the Sun’s heat and light rays.

Juno has been navigating in deep space since 2011. It entered an initial 53-day orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Originally, the mission planned to reduce the size of its orbit a few months later to shorten the period between science flybys of the gas giant to every 14 days. But the project team recommended to NASA to forgo the main engine burn due to concerns about the spacecraft’s fuel delivery system. Juno’s 53-day orbit provides all the science as originally planned; it just takes longer to do so. Juno’s longer life at Jupiter is what led to the need to avoid Jupiter’s shadow.

“Ever since the day we entered orbit around Jupiter, we made sure it remained bathed in sunlight 24/7,” said Steve Levin, Juno project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Our navigators and engineers told us a day of reckoning was coming, when we would go into Jupiter’s shadow for about 12 hours. We knew that for such an extended period without power, our spacecraft would suffer a similar fate as the Opportunity rover, when the skies of Mars filled with dust and blocked the Sun’s rays from reaching its solar panels.”

Without the Sun’s rays providing power, Juno would be chilled below tested levels, eventually draining its battery cells beyond recovery. So the navigation team set devised a plan to “jump the shadow,” maneuvering the spacecraft just enough so its trajectory would miss the eclipse.

“In deep space, you are either in sunlight or your out of sunlight; there really is no in-between,” said Levin.

The navigators calculated that if Juno performed a rocket burn weeks in advance of Nov. 3, while the spacecraft was as far in its orbit from Jupiter as it gets, they could modify its trajectory enough to give the eclipse the slip. The maneuver would utilize the spacecraft’s reaction control system, which wasn’t initially intended to be used for a maneuver of this size and duration.

On Sept. 30, at 7:46 p.m. EDT (4:46 p.m. PDT), the reaction control system burn began. It ended 10 ½ hours later. The propulsive maneuver — five times longer than any previous use of that system — changed Juno’s orbital velocity by 126 mph (203 kph) and consumed about 160 pounds (73 kilograms) of fuel. Thirty-four days later, the spacecraft’s solar arrays continued to convert sunlight into electrons unabated as Juno prepared to scream once again over Jupiter’s cloud tops.

“Thanks to our navigators and engineers, we still have a mission,” said Bolton. “What they did is more than just make our cyclone discovery possible; they made possible the new insights and revelations about Jupiter that lie ahead of us.”

NASA’s JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

More information about Juno is available at:

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu

More information on Jupiter is at:

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-672-4780

alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

Deb Schmid

Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio

210-522-2254

dschmid@swri.org

2019-248