Name: Danny Glavin

Title: Associate Director for Strategic Science

Formal Job Classification: Research scientist

Organization: Code 690, Solar System Exploration, Sciences

Danny Glavin – Looks for the building blocks of life in Antarctica’s meteorites.

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

My job has two components. I’m the associate director for strategic science in the Solar System Exploration Division. I serve as a voice for our division’s scientists, including their research interests and visions for future activities, making sure we are well represented within Goddard, NASA Headquarters and the science community at large.

Strategic science means looking at all the different research activities in our division and matching people with similar goals to form strong collaborations. It also means looking ahead five to 10 years to try to predict what NASA will be doing at a high level. We want to make sure that our research is supporting the key NASA science goals and objectives so we maximize our resources and people by putting them into the most promising areas.

The second part of my job is astrobiology research. I study the organic composition of extraterrestrial materials, such as meteorites and interplanetary dust particles, which are pieces of asteroids and comets. I examine their organic chemicals, the building blocks of life, including amino acids and the components of DNA.

Why and how did you become an astrobiologist?

After I got a physics degree from the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), I thought that I wanted to study astrophysics, in particular black holes. I graduated the summer of 1996 and got a NASA summer internship in exobiology, the study of the origin and evolution of life on Earth and the search for life elsewhere, at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), part of UCSD. This was the only summer internship I was offered at the time, so I took it.

What happened during the internship was pretty exciting. NASA announced that they had found signs of life in a Martian meteorite discovered in Antarctica called Allan Hills 84001, a conclusion that is still debated to this day. Nevertheless, the Allan Hills meteorite completely reenergized the astrobiology community. Soon after, NASA formed the Astrobiology Institute to help develop the field of astrobiology and future missions. Everyone wanted to learn more about the origin of life and we had a renewed hope about the possibility of life on Mars.

As a young researcher, I quickly realized that I needed to learn organic chemistry if I wanted to get involved in searching for evidence of life on Mars, which was primarily about chemistry. If you’re looking for ancient signs of life, you look for the chemical fingerprints; so you have to understand organic chemistry.

I took some organic and biochemistry courses at UCSD and then got into the Ph.D. program in earth sciences at SIO. My supervisor during the summer internship became my Ph.D. adviser, who helped me get a NASA fellowship for graduate school.

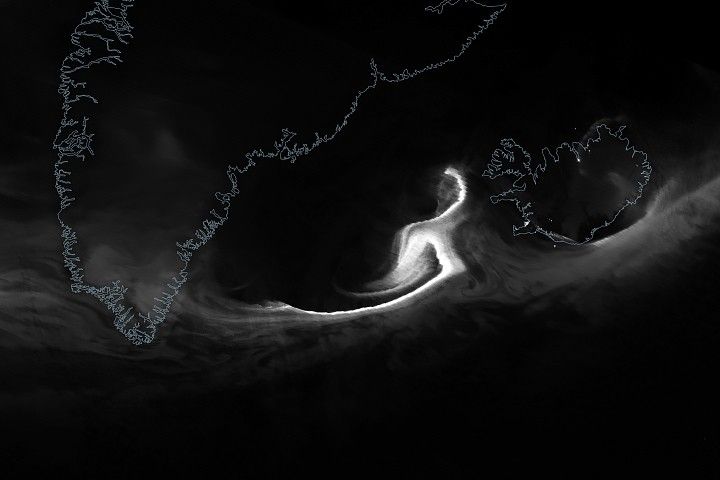

Where do you find Martian meteorites?

Meteorites fall everywhere on the Earth but it’s much easier to find them on land. The Antarctic ice sheet is one of the best places in the world to recover meteorites. The black meteorites, burned from entering our atmosphere, show up well on the blue ice. Also, it is very dry and cold in Antarctica, and there are very few people and animals there to contaminate the samples. It’s a very pristine environment. When looking for chemical evidence of extraterrestrial life, we don’t want to be fooled by contamination from the Earth.

Please tell us about your field work in Antarctica.

In 2002, I spent nearly six weeks in Antarctica at a remote field camp in the MacAlpine Hills region of the Transantarctic Mountains. The mountains provide areas that can accumulate meteorites on the ice over time which are called blue ice fields. The Antarctic Search for Meteorites, a partnership between NASA, the National Science Foundation and Case Western Reserve University, sends a team of scientists, engineers, astronauts, writers, teachers and many other professionals to search for and collect meteorites from the ice using snowmobiles and by foot.

We go for the Antarctic summer, which is winter here. We leave around mid-November and return mid-January. During the Antarctic summer, there are 24 hours of daylight. The sun just circles above the horizon, which can make sleeping a challenge.

Every meteorite hunter has to pass a physical and dental exam. They also take a week-long safety and survival training course at McMurdo Station, a U.S. research station on the southern tip of Ross Island off the coast of Antarctica.

That summer, our team of 12 recovered more than 900 meteorites and a few “meteo-wrongs,” terrestrial rocks that we picked up by mistake. We bagged the rocks, labeled them and put them into ice coolers to keep them organized and to prevent contamination. We sent the rocks to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum in Washington where they are classified to determine their origin.

What was the most exciting about doing fieldwork in Antarctica?

The biggest thrill for me was finding a football-size rock from space on top of the ice. Nobody else had likely ever seen this meteorite before. This rock turned out to be a piece of an asteroid, but not from Mars. It was still an exciting find. We love to find large meteorites because they provide more samples for scientists to study.

Are you planning to do more field work in Antarctica?

There is a saying: “Every day you’re in Antarctica, you think about the day when you’re going to leave. And when you get back home, you spend every day thinking about how you’re going to get back.”

I often think about going back and I’d love to return. It was one of the highlights of my career. But I don’t want to miss spending Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s with my wife and two young boys.

Who is the most interesting, inspiring or amazing person you have met or worked with at Goddard?

My former supervisor, Paul Mahaffy, showed me what it means to be a true leader. He encourages the scientists in his group to work independently and gives them opportunities to take on new challenges. He provides them with an environment in which they can grow and become leaders themselves. He is not the type of person who needs to receive all the credit.

He is also one of the hardest-working people I know. He is extremely dedicated to his job, building mass spectrometer instruments for spaceflight.

What was one of the most surprising moments of your career?

I was very pleased and surprised when the International Astronomical Union named main belt asteroid 2000 WA191 the 24480 Glavin.

Is there something surprising about you, your hobbies, interests or activities outside of work that people do not generally know?

I grew up in San Luis Obispo, California, where I learned to surf when I was 10. I even surfed in a couple of long boarding competitions in San Diego.

What was your favorite comfort food in Antarctica?

I love Mexican food, especially shrimp soft tacos.

OF NOTE:

- Antarctica Service Medal of the United States (2003)

- The Meteoritical Society Nier Prize (2010)

- NASA Goddard Internal Research and Development (IRAD) Innovator of the Year Award (2007)

- NASA Robert H. Goddard Exceptional Achievement Award-Science (2009)

- NASA Robert H. Goddard Exceptional Achievement Award-Science (2014)

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.