Near Earth’s North and South poles, wispy, iridescent clouds often shimmer high in the summertime sky around dusk and dawn. These night-shining, or noctilucent, clouds are sometimes spotted farther from the poles as well, at a rate that varies dramatically from year to year. According to a new study using NASA’s Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) satellite, which is managed by the Explorers Program Office at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, morning rocket launches are partly responsible for the appearance of the lower-latitude clouds.

“Space traffic plays an important role in the formation and variation of these clouds,” says Michael Stevens of the Naval Research Laboratory, the lead author of a paper reporting the results in the journal Earth and Space Science. This is an important finding as scientists are trying to understand whether increases in noctilucent clouds are connected to climate change, human-related activities, or possibly both.

First documented in the late 1800s, noctilucent clouds are the highest clouds in our atmosphere. While rain clouds typically ascend no more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) above Earth’s surface, noctilucent clouds float some 50 miles (80 kilometers) high in a layer of the atmosphere called the mesosphere. (Because of this, they are also known as mesospheric clouds.) They shine at night because they’re so high up that sunlight can reach them even after the Sun has set for observers on the ground. These high-flying clouds form when water-ice crystals condense on particles of meteoritic smoke – tiny bits of debris from meteors that have burned up in our atmosphere.

Noctilucent clouds most commonly appear at high latitudes, near Earth’s poles (where they’re also known as polar mesospheric clouds), but they sometimes emerge farther from the poles, below 60 degrees latitude. Between 56 and 60 degrees north latitude (above areas such as southern Alaska, central Canada, northern Europe, southern Scandinavia, and south-central Russia), for example, the frequency of these clouds can vary by a factor of 10 from one year to the next.

Previous studies showed that water vapor released into the atmosphere by space shuttle launches can cause an increase in noctilucent clouds near the poles. “The prevalence of noctilucent clouds at mid-latitudes, however, has been cloaked in mystery and the underlying cause disputed,” Stevens said. The last space shuttle launched in 2011, but other rockets have carried satellites and people into space since then, adding water vapor to the atmosphere. “This study shows that space traffic, even after space shuttle launches were discontinued, controls the year-to-year variability of mid-latitude noctilucent clouds,” Stevens concluded.

Stevens and his team studied observations of noctilucent clouds taken by the Cloud Imaging and Particle Size (CIPS) instrument on NASA’s AIM satellite, which launched in 2007 to investigate why night-shining clouds form and vary over time.

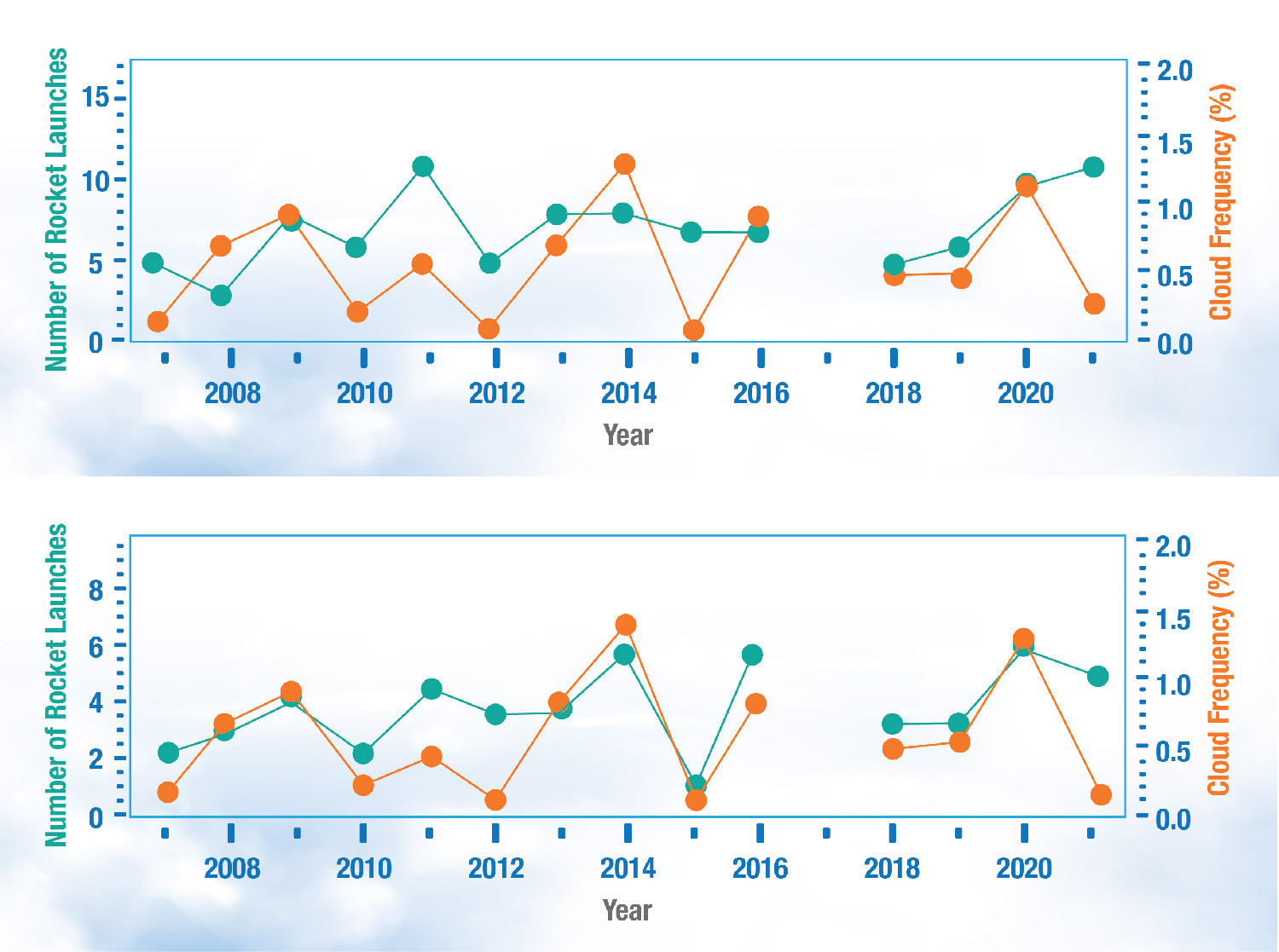

The team compared AIM’s observations to the timing of rocket launches south of 60 degrees north latitude. The analysis revealed a strong correlation between the number of launches that took place between 11 p.m. and 10 a.m. local time and the frequency of mid-latitude noctilucent clouds observed between 56 and 60 degrees north latitude. In other words, the more morning launches there were, the more mid-latitude noctilucent clouds appeared.

The researchers also analyzed winds just above noctilucent clouds and discovered that northward-traveling winds were strongest during these morning launches. This suggests that winds can easily carry the exhaust from morning rocket launches at lower latitudes, such as from Florida or southern California, toward the poles. There, the rocket exhaust turns into ice crystals and descends to form clouds.

In addition, the observations revealed no general upward or downward trend in the frequency of mid-latitude noctilucent clouds over the duration of the study, nor any correlation between their frequency and the 11-year solar cycle, indicating that changes in solar radiation are not causing the clouds to vary from one year to the next.

“Changes in the number of noctilucent clouds at mid-latitudes correlate with morning rocket launches, consistent with the transport of exhaust by atmospheric tides,” Stevens concluded.

“This research, relating changes in mesospheric cloud frequency to rocket launches, helps us to better understand the observed long-term changes in the occurrence of these clouds,” said NASA Heliophysics Program Scientist John McCormack at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, who contributed to the study.

As the atmosphere near Earth’s surface warms, the mesosphere cools and more water vapor ends up in the upper atmosphere. Both effects could make it easier for water crystals to condense and noctilucent clouds to form. AIM’s observations, along with efforts to model the cloud formation processes under changing atmospheric conditions, are helping scientists understand how much changes in noctilucent clouds are naturally induced and how much are influenced by human activities.

By Vanessa Thomas

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.