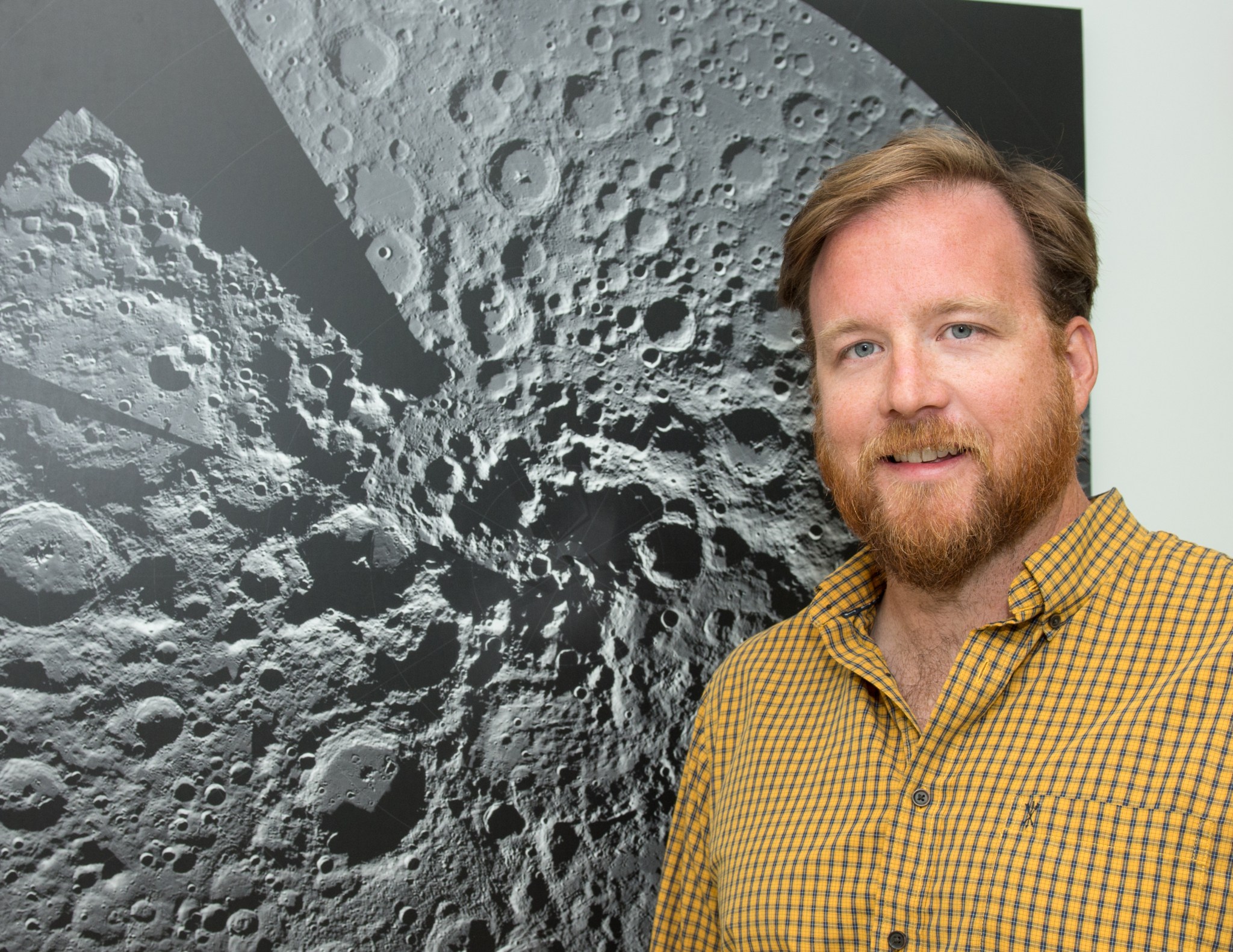

Name: Patrick L. Whelley

Title: Planetary Geologist

Organization: Code 698, Planetary Geology, Geochemistry and Geophysics Laboratory; Solar System Exploration Division

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I’m a planetary geologist and volcanologist. I study volcanoes on Earth, typically those in Hawaii, Iceland and the American Southwest (New Mexico and Arizona) to better understand how lava flows and how volcanic deposits are formed. I measure the topography of volcanic deposits using a light detection and ranging (lidar) instrument, basically a big, fancy laser pointer. Our work helps us understand how the crusts were formed on the Moon and Mars, as well as here on Earth!

When and why did you decide to become a volcanologist?

I grew up in rural New Hampshire. My teachers suggested I apply to the Earth Watch Program, which sent me to Arizona State University for two weeks to study planetary science. It was fascinating! The fact that you could look at picture of a planet and do experiments in a lab and then reconstruct the history of the planet’s formation and surface processes really intrigued me. I wanted to ask questions and find out answers.

So I decided to go to Arizona State University, where I got a bachelor’s and master’s degree in geology. Still fascinated by volcanoes, I got a Ph.D. in geology, emphasis in volcanology, from State University of New York at Buffalo. The university does not have a degree in volcanology, but they do have a lot of volcanology professors, which allowed me to specialize in volcanoes.

What did you study in Singapore during your post doc?

I did a two-year post-doc at the Earth Observatory of Singapore. Singapore is worried about geohazards like earthquakes, volcanoes and tsunamis. My research was looking at the probability of volcanic ash interrupting air travel. It was an opportunity to go to a place that was dynamic geologically and professionally and work on an interesting problem.

What brought you to Goddard?

While I was at Buffalo, I was a Graduate Student Research Program fellow, which allowed me to work with Drs. Lori Glaze and Jacob Bleacher of Goddard. When I finished in Singapore, I came to Goddard as a NASA post-doctoral fellow working with Brent Gary and Jake Bleacher.

Do you have any favorite field work stories?

This past summer, I led a 17-person team to Iceland to study a new lava flow with lidar. We also studied the habitability of the intersection of lava flows and glaciers. Iceland has some volcanoes capped with glaciers and others adjacent to glaciers, environments might be analogs for places on Europe or ancient Mars. We go to these places to learn what kinds of critters live in these environments.

Why were you camping at the base of an active super volcano?

We were camping in the highlands of Iceland in volcanic ash and rocks. It rains a lot there too. We were at the foot of Askja Volcano, an active super volcano. A super volcano means that if the volcano erupts, it could be a big day! The local university monitors the volcano’s activity and closes the park if an eruption is imminent, which has a low probability.

Your wife, Nicole, is also in your lab. How does that work?

My wife Nicole is also a geologist in our lab. She was the logistics coordinator for our field trip to Iceland. She also does communications and public outreach. She has taught fieldwork workshops at the base of other volcanoes. So she absolutely understands why we’re sleeping at the base of an active super volcano.

Although we work for the same laboratory, we have different expertise and generally work with different people.

Why did you spend a week and a half inside of lava tubes?

A lava tube is a cave formed by flowing lava that drained before it cooled. The cave is encased by solidified lava. The sizes range from subway tunnels to little crawl spaces.

This past fall, I was part of Dr. Kelsey Young’s team that went to Lava Beds National Monument in northern California. We were trying to figure out the shape of lava tubes and map out the insides using lidar. To find these lava tubes from the surface, we used magnetometers, ground-penetrating radar and a gravimeter, a gravity-measuring device. We then compared the answers from the surface and the subsurface tools. Our research will help better understand how to find and explore lava tubes on other planets.

We spent every day exploring the lava tubes. I didn’t get claustrophobic because I always knew the way to get out. I have to admit that parts were pretty tight squeezes.

Do you ever get scared exploring volcanos?

One time my wife and I, along with my uncle Dave and friend Annie, were tourists on vacation at the Krakatau Volcano in Indonesia. Our tour guide took us up near the active dome. I picked up a rock about the size of a fist, broke it open as geologists do and it was hot on the inside. I knew that the volcano had thrown this rock out within the past few days. I realized that we were too close and got very nervous. I told the group what I found and told the guide that we needed to turn around. So the group climbed down.

What special safety precautions do you take when doing volcanic fieldwork?

Safety is always a major concern whenever we are doing fieldwork. To be safe, when exploring lava tubes, we wear caving helmets with lights, kneepads and leather gloves. When exploring volcanoes, we wear high-visibility neon vests; sturdy, rubber-soled, leather boots; gators; leather gloves and helmets.

Fieldwork protocol is to always operate in pairs and stay within sight of your partner. Every pair has a known time and place to rendezvous with the entire group at the end of the day. It’s like the buddy system for swimming lessons.

I have also taken several courses in wilderness rescues, first aid and related field training.

What is your favorite volcano?

Lascar in Chile where I did a lot of Ph.D. work. Lascar has beautiful, pumice flows that are so pristine that they look like they erupted yesterday. The pumice is white and the ground under the lava is more pink and yellow. Lascar is high in the Andes where it is a very, very dry desert. Lascar is also the first place where I figured out how a pumice deposit forms.

Is there something surprising about your hobbies that people do not generally know?

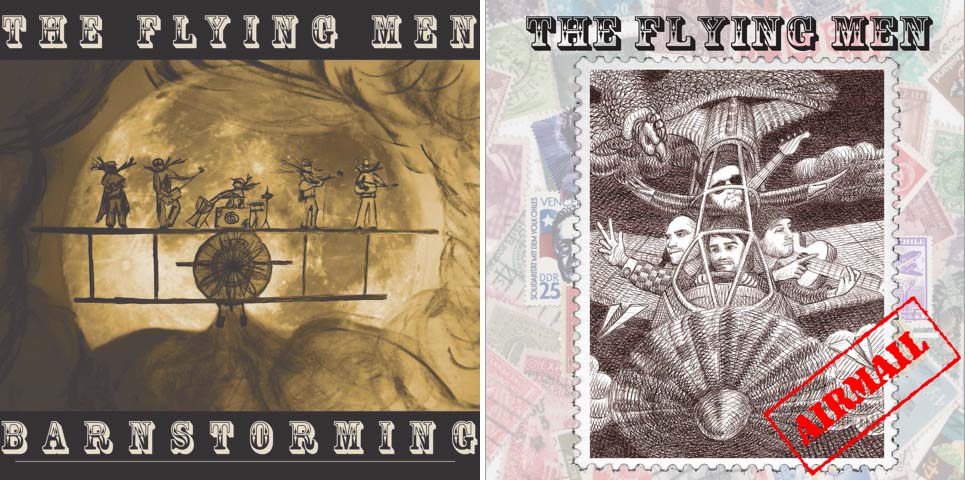

I play bass guitar. When in Buffalo, I was in a band called “The Flying Man” and we made a few albums, which are still available on iTunes. We played American folk rock. I sang a little backup on these albums. I also helped design the album covers.

While I’m not currently in a band, I do sing at bedtime to our two young boys, ages 2 years and 6 months. Our eldest likes to sing and play harmonica. He’s good and can project his voice very well.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center