Name: Manisha Ganeshan

Title: Atmospheric scientist

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Laboratory, Sciences and Exploration Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

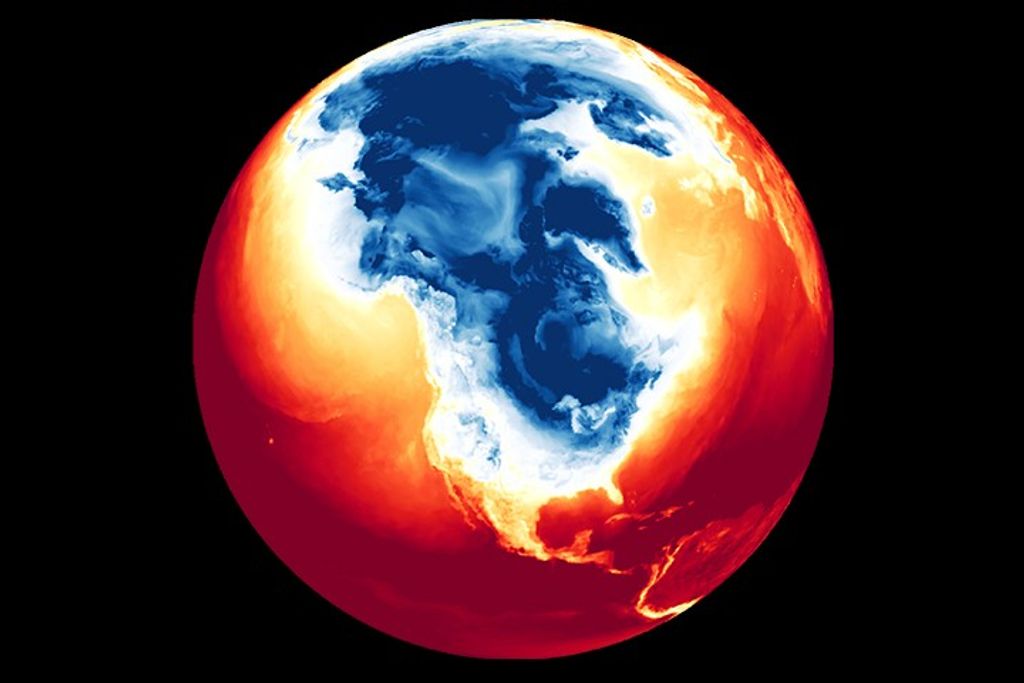

I study the atmospheric boundary layer, which is the part of the atmosphere that interacts with the Earth’s surface, be it land, ocean or ice. In polar regions, these interactions, among other things, are important for understanding how much energy is available for melting the ice. If all of the thick ice over Antarctica and Greenland melted, it could cause global sea levels to rise more than 200 feet. In a warming world, coastal cities like New York and Mumbai, my home city, are at high risk.

I study both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. I am also a 2017 Fellow of the International Arctic Science Committee.

What inspired you to become an atmospheric scientist?

When I was about 3 or 4 years old, my dad, who worked in publishing, would read sections of the encyclopedia to me about planet Earth and animals. I was always fascinated about the space between the Earth and the Sun, how the Earth was formed and how we came to be.

I was born in Bombay, now called Mumbai. In Mumbai, we finish the equivalent of high school at 18. After high school, I attended the Kolhapur Institute of Technology in Kolhapur, which is about 250 miles south of Mumbai, where I got a degree in environmental engineering. I was interested in air pollution studies at the time.

While there, in July 2005, Mumbai suffered the catastrophic Maharashtra Floods resulting in record 37 inches of rainfall within 24 hours. These floods were not predicted; they caught everyone by surprise. The city of Mumbai, India’s financial capital, stopped dead for almost a week. There was literally no movement.

My family and I were OK. But strangers knocked on our door seeking shelter because they had nowhere else to go. It was life changing. So I wanted to learn more about how such tremendous floods could happen to at least try to help everyone be more prepared.

The 2005 Maharashtra Floods were a wakeup call, to the city and to me.

After the wakeup call from the Maharashtra Floods in Mumbai, what did you decide to do?

I certainly wondered about the possible role of global warming in causing these floods and started educating myself about climate change. While in my third year at the Kolhapur Institute of Technology, I began working on an honors project exploring harvesting local geothermal energy. Thanks to my mother’s encouragement and this project, I was one of two students from India selected to participate in the Bayer Young Environmental Envoy Program and their environmental field trip in Germany. I spent about a week in Germany with students from 16 different countries including nations in Asia, Africa and the Americas. We were trying to make a positive impact by helping local communities develop sustainably and understand and cope with climate change.

What did your first international science exposure prompt you to do?

This field trip made me decide to pursue a graduate degree in climate science. The University of Maryland, with its highly ranked department and world-class faculty, was an easy choice, and its proximity to Goddard was an added bonus. I had always dreamed of working at NASA.

In the fall of 2008, I began studying at the University of Maryland, College Park. In December 2013, I earned a Ph.D. in atmospheric and oceanic science. Concurrently, I had a graduate student fellowship from NASA, which allowed me to use Goddard’s supercomputers for my thesis research. I was modeling summer thunderstorms over the U.S. to improve prediction of times and amounts of heavy rain. I also studied the impact of urban land cover, primarily concrete, on the intensity and track of thunderstorms.

How did you move from studying the boundary area of thunderstorms to the polar boundaries?

I met Dr. Dong Wu from Goddard’s Climate and Radiation Laboratory when he gave a seminar at Maryland. After his talk, we discussed my work on modeling thunderstorms and he offered me a postdoc fellowship to use GPS satellite data to study the atmospheric boundary layer in polar regions. My knowledge about the physics of the boundary layer, which I had applied to thunderstorms, was useful in my new work.

My main project initially was to use satellite remote sensing to measure the lower atmosphere over the Arctic Ocean, where conventional and field campaign observations are very sparse. Our algorithm can successfully measure the Arctic atmosphere’s boundary layer properties during winter months.

Presently, I’m studying the Antarctic continent using field campaign, remote sensing, and model data to get a comprehensive picture of its boundary layer and turbulence.

How does your current project at Goddard relate back to the 2005 Maharashtra Floods?

I have never forgotten the total, swift and unpredicted devastation of the Maharashtra Floods.

I remain in this lab and now work for Dr. Yukeui Yang. Studying Antarctica is actually a bit of a paradox. It is a desert, one of the driest areas on Earth. But the common element is the challenge of accurately predicting vertical motion at very fine scales which is important for forecasting heavy rainfall and surface-atmosphere interactions in polar regions.

Recently, I began working on a new project for Dr. Oreste Reale, from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office, studying tropical cyclones (hurricanes) and how to better predict them. In fact, hurricane-like storms can form in the colder polar oceans too, and I’m learning that they’re deeply similar to tropical cyclones by nature.

What is your role as a 2017 Fellow of the International Arctic Science Committee?

The International Arctic Science Committee is a scientific organization with council members from about 23 different countries including the U.S. and India. They have five core scientific working groups. In 2017, I was pleased to be inducted as a fellow into their atmospheric working group.

It’s exciting to be able to participate in scientific efforts on an international scale. Recently, I co-organized an “Arctic Extreme Events” workshop that was held in Davos in June 2018. The participants included 15 international scientists from a diverse background. Together, we worked to better understand and characterize anomalous events that affect our geographic North Pole. We plan to produce a summary paper highlighting our key recommendations to the wider community.

I’m also helping organize a meeting for the Year of Polar Predictions (YOPP) next year in Helsinki. The YOPP is a large international effort to collect data from a suite of instruments, satellites and models, with the goal of improving weather and climate predictions over the poles and beyond. The weather can quickly and quite severely change in polar regions.

How do you feel being so far from your family?

My parents and family remain in Mumbai. I grew up with a lot of close cousins in a big, extended family. Family is very important to me. I try to go home for about a month each year starting mid-December. It takes on average 22 hours to go home, so it is a long journey.

Here, I am immersed with my work and only meet friends, all of them new, during weekends. Life in Mumbai is a big contrast. I am surrounded by people, quite literally, and I socialize a lot. I call it my chaotic peace.

Do you have any hobbies?

Back home, I learned classical Indian dance, Bharata Natyam. Here, I am learning yoga.

What is your one big dream?

I had dreamed of working at NASA since I was 11 years old, a dream which came true.

My current dream is to connect my research with people, to help communities that are particularly vulnerable to climate risks. Some of the densest populations of the world live in coastal cities. So I hope that my research and efforts to improve predictions of sea level rise and tropical storms will ultimately be useful to people.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center