For a companion piece about this topic in Spanish, please click here.

Around the globe, societies are grappling with how life will move forward in the face of COVID-19. In many communities, people are starting to emerge from isolation: workers are headed back to their commutes, theaters are reopening, and students are going back to school in person.

As they do, many are entering a new normal. “On a psychological level, there’s a lot to deal with,” explained Alexandra Whitmire, who helps manage psychological research supported through NASA’s Human Research Program, or HRP. There’s the illness and loss of loved ones, the stress of long-term sickness, the anxiety associated with being careful and vigilant against infection, and the worry of future sickness. “Added to that is a slightly different stressor that involves emerging from isolation,” she continued.

In some ways, the psychological toll may mirror what astronauts face when they return to Earth, and what analog crews feel when they rejoin society, Whitmire noted. Depending on the length of the mission, some astronauts and analog crews can take months to fully re-adapt when they return home.

Although the post-flight experiences of astronauts are not completely parallel to pandemic adaptations, “there may be touchpoints where we can relate with what astronauts have experienced,” Whitmire said.

So what can NASA crews who adjusted to life after their missions teach us about how to adjust to life after living in quarantine? Here are five lessons from astronauts, crew members from ground-based analogs, and NASA-affiliated psychologists.

1. You may miss the upside of inside.

Living and working inside an isolated environment is challenging. But, as astronauts note, it also has upsides.

For example, some astronauts experience a powerful shift in perspective, known as the “overview effect,” when viewing Earth from space, explained author Frank White in an episode of Houston We Have a Podcast. The effect often generates feelings of wonder and awe in crews. In a similar fashion, pandemic life could refocus priorities for many who have enjoyed spending more time with their families, or who are eager to reexamine their work-life balance.

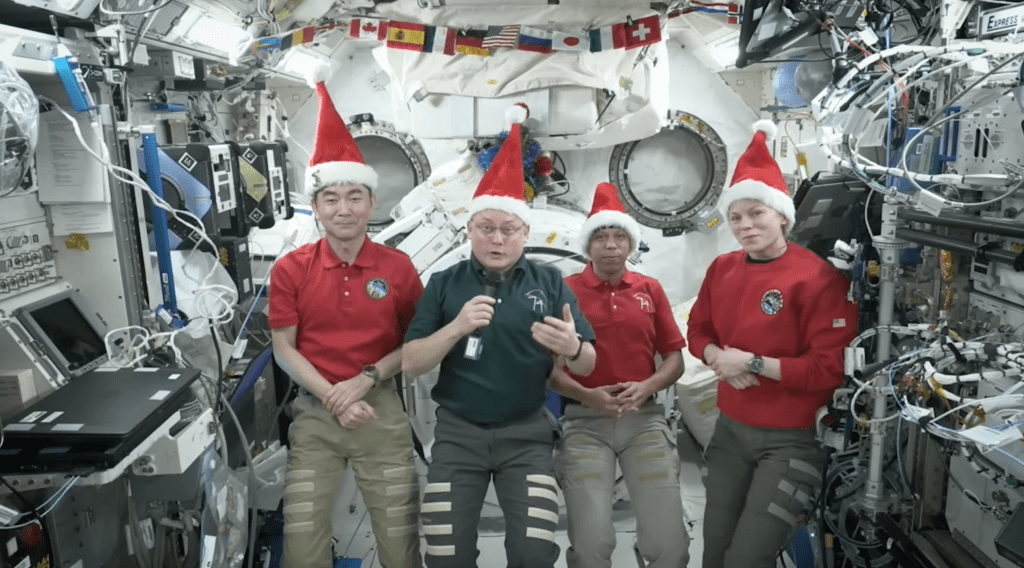

Other astronauts say having a clear idea in space of what needs to be done without competition for your time can be liberating. “Working aboard the International Space Station, from the time you wake up in the morning until you go to bed at night, it’s just constant movement, constant activity, constant action,” explained NASA astronaut Mike Hopkins, who served as commander on NASA’s SpaceX Crew-1 and as a flight engineer for Expedition 64. The work of a new mission, and establishing a new normal off Earth, brought a sense of clarity and purpose, Hopkins noted. Once back, you can miss having that sense of purpose.

“You almost have to reset,” he explained. “You’ve got to rethink your priorities, rethink: What’s my goal now?”

2. Daily routines may need adjusting.

Once a mission ends, crews must quickly adjust to new daily routines on Earth. Sound familiar?

“I think we all are creatures of habits,” Hopkins explained. When he landed back on Earth, “All of a sudden I’ve got to figure out what I’m doing the rest of the day.” Hopkins noted it took him a few weeks to fall into the groove of a different routine after his missions. Breaking old routines and forming new ones, “I think that’s the same thing that people are going to experience as they come back from COVID isolation.”

Sara Whiting agrees. Whiting is a research psychologist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where she studies the effects of spaceflight on the behavioral health and performance of crews. “After spaceflight, the transition from a mission-oriented mindset with clear goals and timelines, to an Earth-based mindset with a more traditional routine can be an adjustment,” she said. “The same may be true for some who must resume their pre-pandemic routines, such as commuting to school and work.”

To help adjust to a different routine, Whiting suggests doing what crews do: debrief or assess lessons they learned from their experiences away from normal life. “Look at what worked well and not well,” she said. “It’s a good reflection tool to determine what kind of routines, activities, and coping skills you want to keep or do differently moving forward.”

3. You may feel easily stimulated when adapting to different environments.

Living in an environment closed from the rest of society can affect certain senses, which may alter your sensitivity to various stimuli when emerging from isolation. Yajaira Sierra-Sastre, who participated in a four-month NASA-funded study at the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, or HI-SEAS, reports exactly this.

After living on the HI-SEAS remote outpost atop the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii, she recalled the initial impression daily activities left on her senses. “The pace of life was quite shocking,” she explained. “I was overwhelmed by automobiles, the fast pace, the noise, but I also experienced a wonderful bliss when I saw the bright blue colors of the sea.”

Similarly, those used to living in quarantine during the pandemic may feel easily stimulated upon returning to busy shopping centers, public transportation, or a crowded work environment. Sierra-Sastre said that fortunately, humans are excellent at acclimating to various places quickly. “Before and during the mission, I asked myself how difficult it will be to adjust to the reality of Earth after I leave this analog mission.” These concerns quickly dissipated after her mission ended, however.

It took Sierra-Sastre a week to readjust to normal life. “It is amazing how easy we can adapt,” she said.

4. Returning to normal interaction with people may be difficult.

Although crews are trained to interact with people from diverse backgrounds and experiences, returning to everyday interactions can still be difficult. For example, when Reinhold Povilaitis emerged from the NEK analog in Moscow after a four-month study, he and his crewmates had to step outside the tightly knit social circle they sewed in isolation.

“I remember coming out and the six of us still moved as a unit,” he explained. “We still traveled everywhere as a complement. That took some time to fade away.” Reminding himself he needed to put more effort into engaging in small talk again helped strengthen his social skills after the mission.

Likewise, when given the opportunity to interact with others, you may be inclined to meet only with those who shared your bubble. As those bubbles expand or burst, Whiting advises we continue to use self- and team-care skills, like respecting each other’s space. “Being aware that everybody may have a different boundary is a really important aspect of transitioning back,” she said. “Start with the folks that you feel the most comfortable with and work your way out.”

5. Choices may seem overwhelming.

After months spent following a strict regimen in an environment with limited resources, crews may feel inundated with choices when they return home. Andrzej Stewart, who participated in an isolation study at HI-SEAS and at the Human Exploration Research Analog, or HERA, in Houston, reported feeling overwhelmed by options when he went to the supermarket after both studies.

“I was shopping for dental floss and there were like 20 different types,” Stewart explained. “It was very easy to get overloaded.” He said starting with small choices and progressively making more decisions helped him embrace his newfound freedom.

Stewart’s gradual approach is a good strategy, Whitmire noted. “Stay the course and take small steps to push past that uncomfortableness, knowing that it’s a new norm for everybody,” Whitmire said.

Returning to the outside world after being sheltered for months can be difficult for nearly anyone, including astronauts. To help, “Crews have a great deal of support once their mission ends,” Whiting said. “A whole team works to help them readjust back to life on Earth.”

As the world moves forward, building similarly strong support networks within and among communities will be key, Whiting explained. “Consider how you can be a good team member to folks, such as those returning to school or the office,” she said. “We’re all in this together, so we’ll need to have a team mentality.”

To learn more about how NASA studies the effects of isolation and confinement on astronauts, click here.

_______

NASA’s Human Research Program, or HRP, pursues the best methods and technologies to support safe, productive human space travel. Through science conducted in laboratories, ground-based analogs, and the International Space Station, HRP scrutinizes how spaceflight affects human bodies and behaviors. Such research drives HRP’s quest to innovate ways that keep astronauts healthy and mission-ready as space travel expands to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.