By Linda Herridge

NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center

Leerlo en espanol aqui.

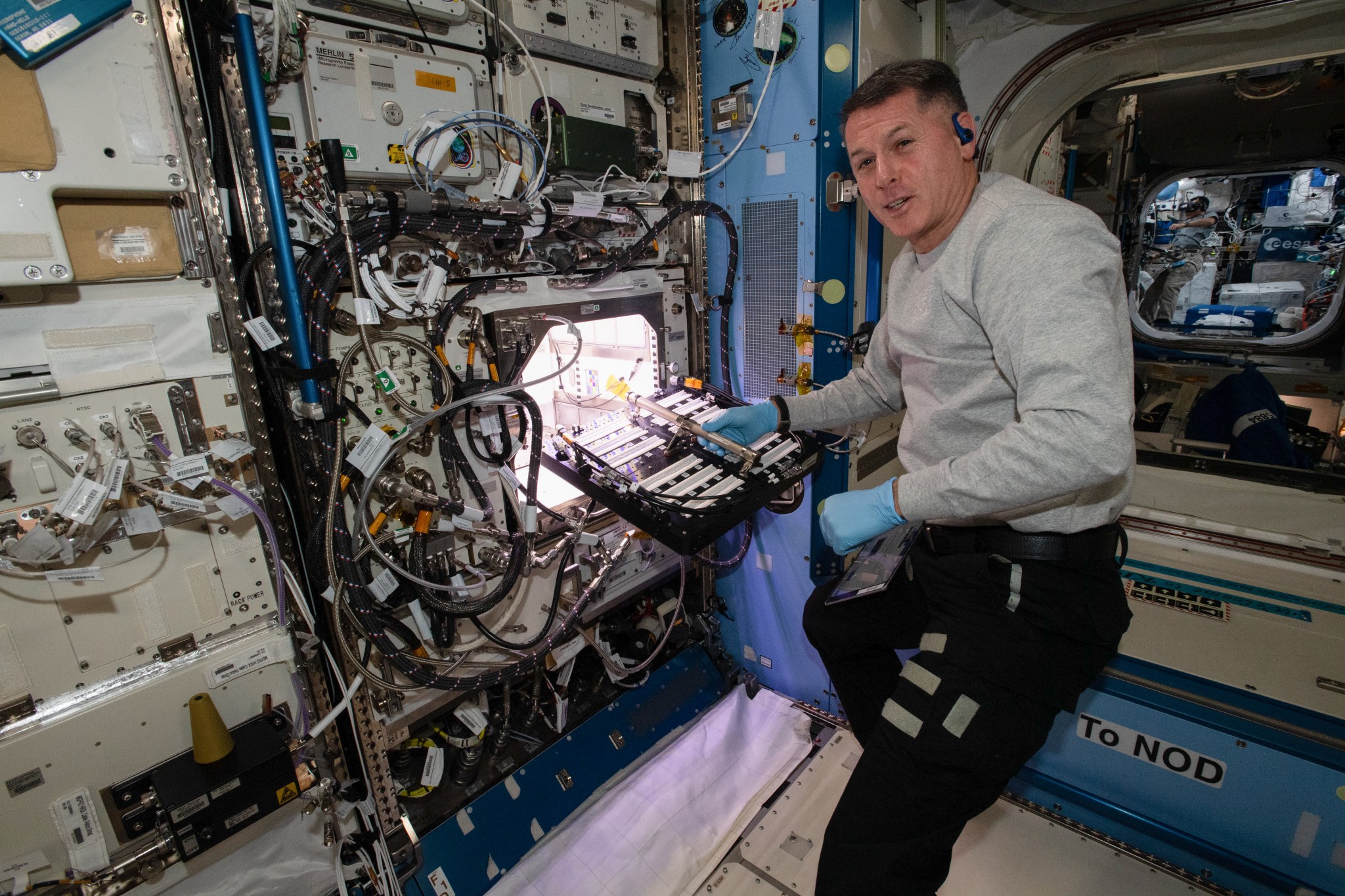

In a few months, fully grown red and green chile peppers should be tempting the taste buds of astronauts on the International Space Station. NASA’s Plant Habitat-04 (PH-04) experiment, containing Hatch chile pepper seeds, arrived at the space station aboard SpaceX’s 22nd commercial resupply services mission in June, and NASA astronaut Shane Kimbrough initiated the experiment.

Kimbrough, a flight engineer who is part of the seven-member Expedition 65 crew, has previous experience growing crops in space, helping to grow and eat ‘Outredgeous’ red romaine lettuce in late 2016. Kimbrough launched to the space station in April as commander for NASA’s SpaceX Crew-2 mission that brought four astronauts to the orbiting laboratory for a six-month science mission.

A team with Kennedy Space Center’s Exploration Research and Technology programs planted the seeds in a device called a science carrier that slots into the Advanced Plant Habitat (APH), one of the three plant growth chambers on the orbiting laboratory in which astronauts raise crops. If successful, PH-04 will add another crop NASA can use to supplement astronauts’ diets on future missions.

“The APH is the largest plant growth facility on the space station and has 180 sensors and controls for monitoring plant growth and the environment,” said Nicole Dufour, PH-04’s project manager. “It is a diverse growth chamber, and it allows us to help control the experiment from Kennedy, reducing the time astronauts spend tending to the crops.”

The peppers will grow for about four months before the astronauts harvest them for the final time. The peppers can be eaten green but turn red when fully ripe. It is the first time NASA astronauts will cultivate a crop of chile peppers on the station from seeds to maturity. The plan is for crew to eat some of the peppers and send the rest back to Earth for analysis, as long as all the data indicates they are safe for the crew to eat.

“It is one of the most complex plant experiments on the station to date because of the long germination and growing times,” said Matt Romeyn, principal investigator for PH-04. “We have previously tested flowering to increase the chance for a successful harvest because astronauts will have to pollinate the peppers to grow fruit.”

Starting in late 2015 and going into early 2016, astronauts grew zinnias on station – a precursor to growing longer-duration, fruit-bearing, flowering crops like peppers.

Before selecting a pepper cultivar to grow aboard the space station, researchers spent two years evaluating more than two dozen pepper varieties from around the world. They narrowed it down and selected the NuMex ‘Española Improved’ pepper, a hybrid Hatch pepper, the generic name for several varieties of chiles from Hatch, New Mexico, and the Hatch Valley in southern New Mexico.

This pepper performed well in testing and had the makings of a viable space crop.

”The challenge is the ability to feed crews in low-Earth orbit, and then to sustain explorers during future missions beyond low-Earth orbit to destinations including the Moon, as part of the Artemis program, and eventually to Mars,” Romeyn said. “We are limited to crops that don’t need storage, or extensive processing.”

Romeyn said that in space, crew members can lose some of their sense of taste and smell as a temporary side effect of living in microgravity, and they may prefer spicy foods or seasoned foods. Peppers are high (dense) in Vitamin C and other nutrients. They are even higher in Vitamin C than some citrus. These traits make peppers an excellent candidate for testing on the space station.

“Growing colorful vegetables in space can have long-term benefits for physical and psychological health,” Romeyn said. “We are discovering that growing plants and vegetables with colors and smells helps to improve astronauts’ well-being.”

To prepare the experiment for the station, researchers at Kennedy sanitized and planted the 48 pepper seeds in the science carrier, which has baked clay for roots to grow in and a controlled release fertilizer specially formulated for the peppers.

Romeyn’s team will monitor the experiment from Kennedy’s Space Station Processing Facility (SSPF), controlling watering, LED lighting, and other environmental conditions. In September, the team will activate and grow a ground control crop of peppers in nearly identical conditions to the orbital crop using an APH inside the SSPF Space Crop Production Facility.

Some of the data PH-04 will collect includes crew feedback on flavor and texture of the peppers, along with Scoville measurements to assess the heat of the peppers grown on the space station and on the ground at Kennedy.

“The spiciness of a pepper is determined by environmental growing conditions. The combination of microgravity, light quality, temperature, and rootzone moisture will all affect flavor, so it will be interesting to find out how the fruit will grow, ripen, and taste,” said LaShelle Spencer, PH-04’s project science team lead. “This is important because the food astronauts eat needs to be as good as the rest of their equipment. To successfully send people to Mars and bring them back to Earth, we will not only require the most nutritious foods, but the best tasting ones as well.”

Download high-resolution photos and videos of the research mentioned in this article.