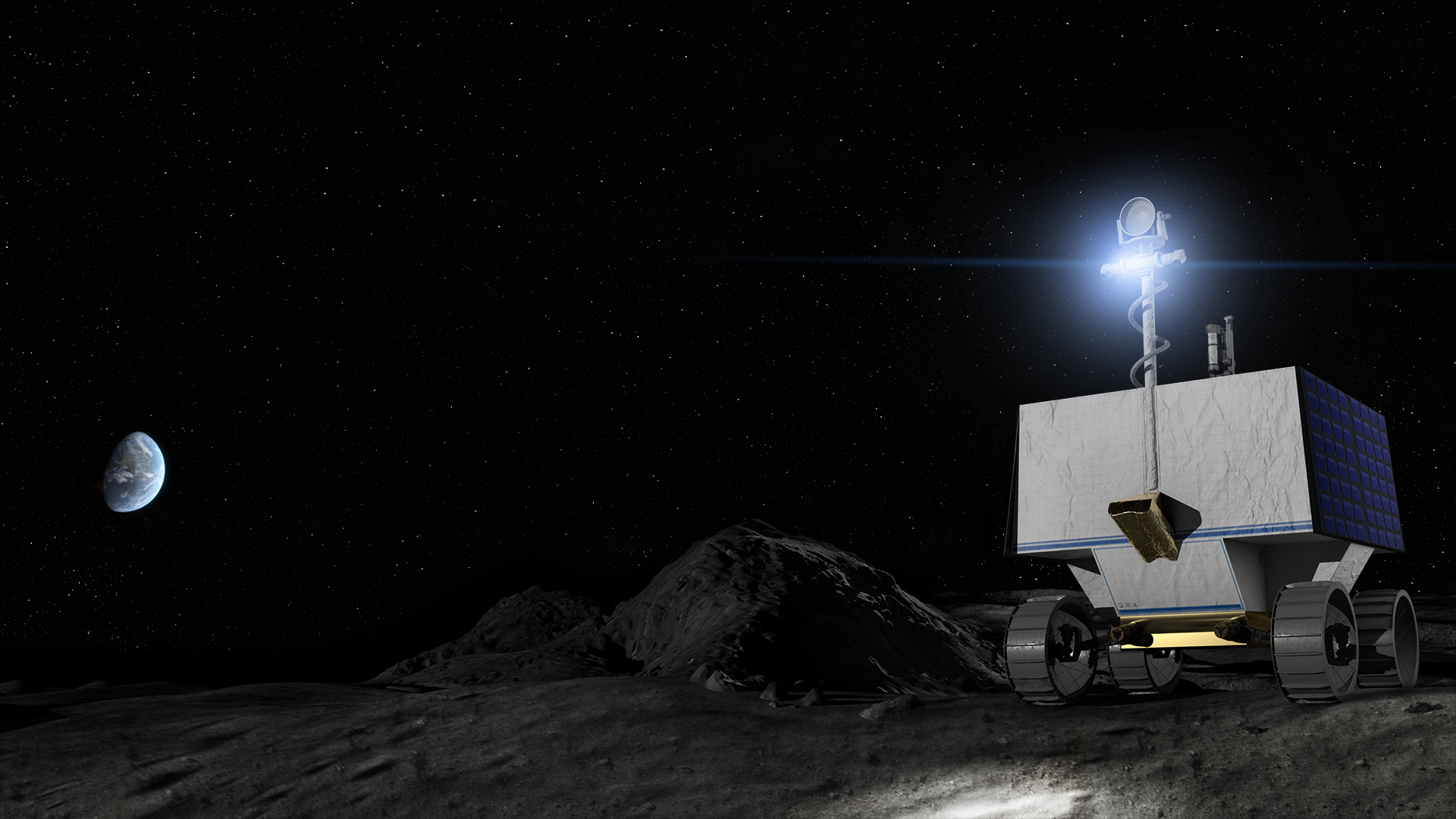

As any seasoned road-tripper knows, to get the most out of an adventure, a good map helps. It’s no different for NASA’s first lunar robotic rover planned for delivery to the Moon in late 2023 to search for ice and other resources on and below the lunar surface. The Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, or VIPER, is part of the agency’s Artemis program. Without a Moon travel guide, VIPER’s mission planners are creating new high resolution, digital elevation maps of the lunar surface.

When equipped with these maps, the rover will be in a better position to safely and efficiently traverse the Moon while looking for resources at the lunar South Pole. Ice is a resource of particular scientific interest as it may have applications if found in space and converted to other resources to further our exploration into the solar system such as oxygen and rocket fuel.

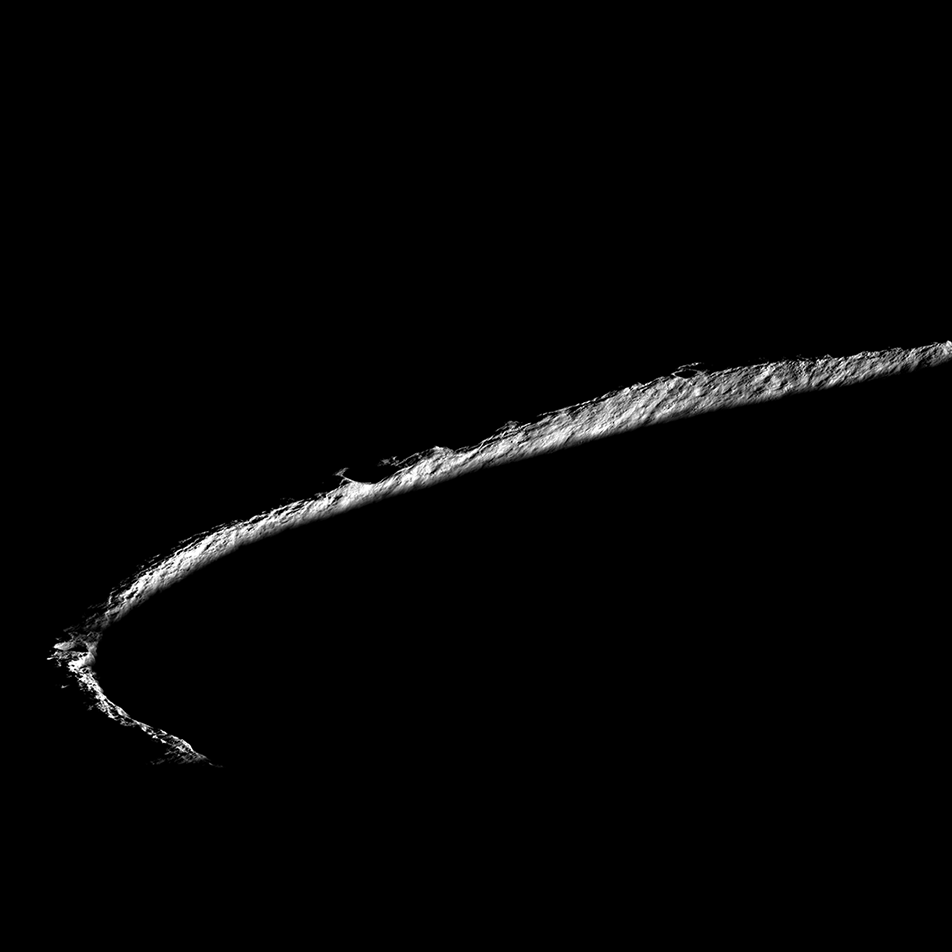

At about three-foot (one-meter) scale, these maps provide a 3D model of large swaths of the terrain at the lunar South Pole and show the ever-changing lighting and temperature conditions caused by long shadows that sweep across the landscape.

Besides preventing the rover from tipping down the edges of steep-sided craters, this up-close view of the Moon’s surface provides mission planners vital information to ensure the rover’s solar-powered batteries stay charged and guide the rover toward safe spots to hibernate during communication blackouts with mission operations on Earth.

“We are sending VIPER to one of the Moon’s most dynamic environments, and the rover needs to be able to take what the Moon gives,” said Anthony Colaprete, VIPER’s project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “That’s why we are creating these unique maps – at human scale – to help us carefully plan routes for the rover while operating safely and collecting the best science possible.”

Already, the maps are revealing new features of scientific interest on the Moon’s surface, including numerous “mini cold traps” – which are shadowed pockets on the lunar surface 6 to 16 feet (2 to 5 meters) across – that could be cold enough for ice to potentially collect. These micro cold traps offer areas to explore in addition to the much deeper and older craters that are a focus of the VIPER mission.

“We used to think of water ice collecting only in deep, dark craters on the Moon,” said Colaprete. “But we now believe that even small, shadowed craters can be cold enough to retain water molecules. These small cold traps are much more common than their larger counterparts, so understanding how they may store water is important to answering the broader question of how water behaves on the Moon.”

To create the elevation maps, a team at Ames is using NASA’s open source Stereo Pipeline software tool as well as the processing power of Ames’ Pleiades supercomputer to layer thousands of satellite images taken by cameras aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Engineers are pairing these powerful tools and expertise with a photo processing capability called photoclinometry. This technique, also known as “shape from shading,” combines the known angles of sunlight with the greyscale levels of many two-dimensional images to infer the three-dimensional shapes of the lunar surface. The resulting model of the lunar terrain allows engineers to calculate how light and shadows play across the surface at any time in the past or future. For example, using the model they can predict the lighting at the time and place the rover will land, and plan the rover’s movements to keep it in sunlight and avoid the shadows.

With the lighting conditions known, the team can create detailed temperature maps across the varied terrain, at the surface, and up to a little more than 8 feet (2.5 meters) below. Temperatures can swing widely between 400 degrees below zero and 170 degrees Fahrenheit, making the Moon’s surface a checkerboard of potentially promising and very unlikely locations to detect ice. Equipped with these new maps, the team can pick spots where ice could be and send VIPER to sample and verify whether ice appears, and if so, how stable it is in various lunar conditions.

“These high-resolution maps have entirely changed our thinking,” said Kimberly Ennico Smith, a deputy project scientist for VIPER at Ames. “We’re beginning to see how extremely varied the soil conditions on the Moon are, even within areas we once thought as fairly uniform. This will allow us to pinpoint the rover’s drill sites much more carefully and lead us to collect even better science data.”

The VIPER team members responsible for keeping the rover humming along have a keen interest in seeing what the rover will face day-to-day – or rather minute-to-minute.

“Shadows move around the South Pole of the Moon at about the same speed the rover drives,” said Mark Shirley, mission operations planning lead at Ames. “We have to plan ahead to avoid VIPER being overtaken by darkness – there’s not much room for error.”

Author: Rachel Hoover, NASA’s Ames Research Center