Skylab 2 astronauts Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Pilot Paul J. Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin, completed their record-setting 28-day mission on June 22, 1973, with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean. Recovery teams from the U.S.S. Ticonderoga recovered the astronauts and their spacecraft. After repairing their damaged Skylab space station, first with a sunshade and later by deploying a jammed solar array, Conrad, Weitz, and Kerwin completed virtually all their planned science objectives and set a record for the longest spacewalk in Earth orbit. Their repairs, unprecedented in the history of spaceflight, not only ensured that Skylab could carry out its full mission supporting the next two record-breaking flights lasting 59 and 84 days, but also set the example of inflight repairs for future programs.

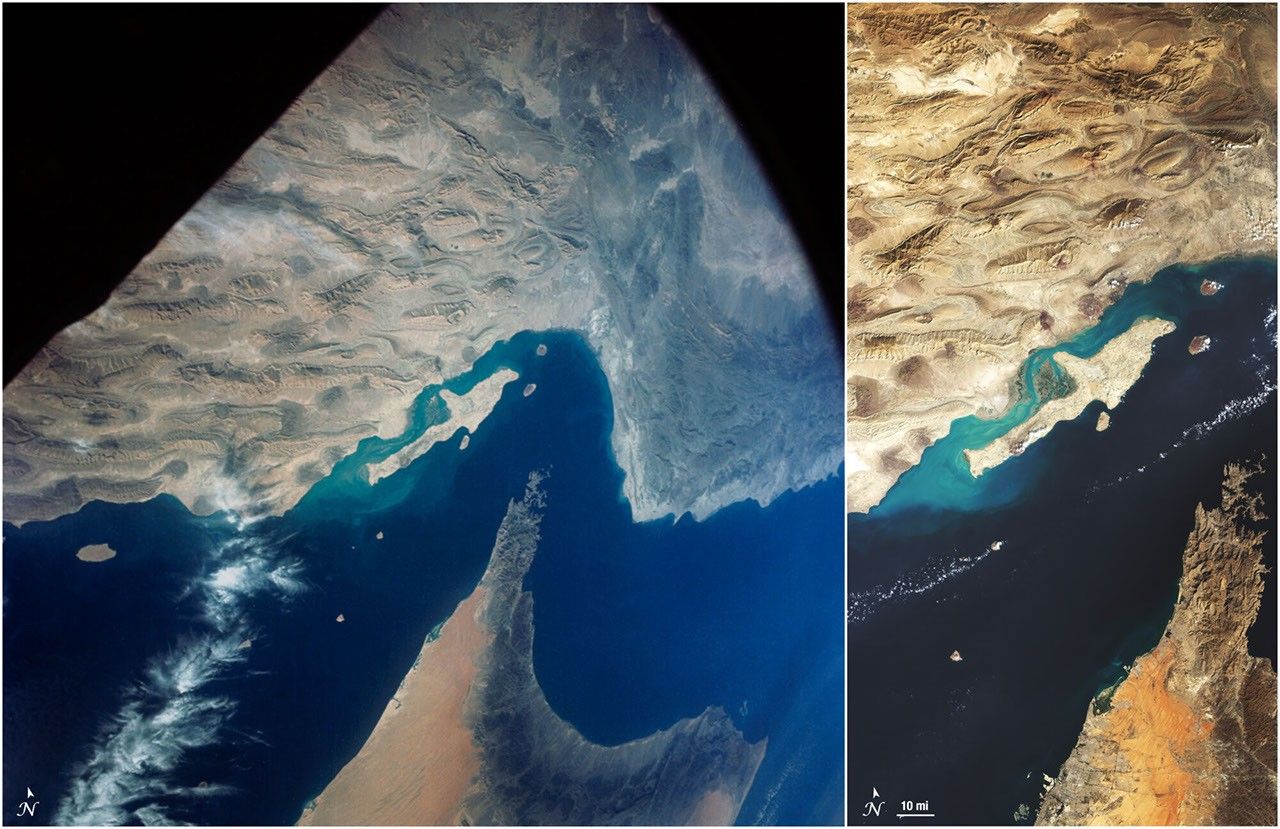

Left: The Skylab 1 space station as seen by the Skylab 2 astronauts during their initial flyaround inspection on their mission’s first day. Middle: The deployment of the parasol sunshade on the mission’s second day, as seen from the Command Module. Right: Skylab 2 astronauts Joseph P. Kerwin (left) and Charles “Pete” Conrad during the spacewalk to free the jammed solar array, photographed by Paul J. Weitz from inside Skylab’s Multiple Docking Adapter.

When the Skylab space station launched on May 14, 1973, aerodynamic forces tore its micrometeoroid and thermal shield from the vehicle. Debris from the shield jammed one its solar array panels while the other tore completely off the spacecraft. Managers delayed the first crew’s launch by 10 days to develop methods to repair the overheated and underpowered space station. When Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz arrived at the station on May 25, they described and recorded the damage. The next day, they deployed a parasol-like sunshield from inside the station that lowered internal temperatures down to comfortable levels. Two weeks into the mission, Conrad and Kerwin deployed the jammed solar array during a spacewalk on June 7, enabling full operations of the station’s experiments.

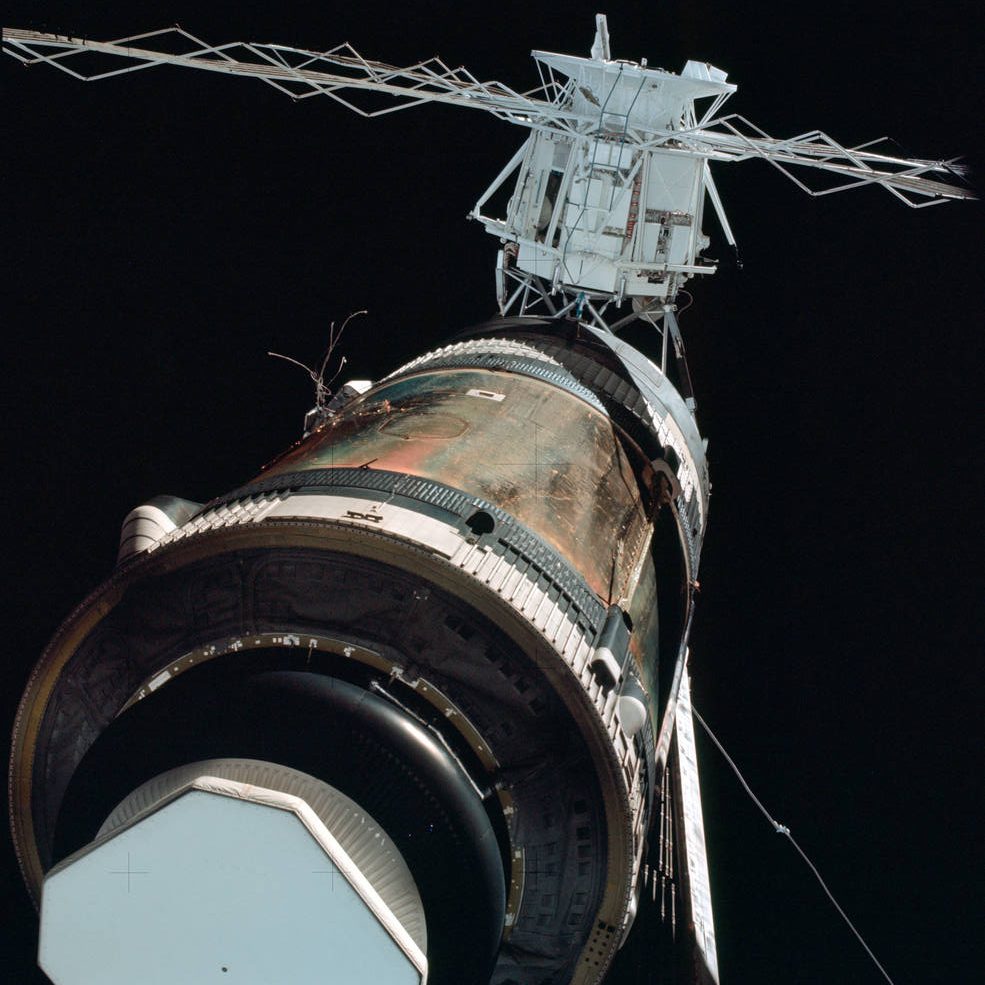

Left: The June 11, 1973, rollout of the launch vehicle for the Skylab 3 mission to Launch Pad 39B. Middle: Skylab 2 astronaut Paul J. Weitz at the controls of the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). Right: X-ray image of the Sun taken by one of the ATM telescopes.

Although never needed during any of the three missions, Skylab astronauts had the availability of an inflight rescue should a malfunction disable their Apollo spacecraft. The Multiple Docking Adapter’s second docking port enabled two Apollo spacecraft to dock with the space station simultaneously. In a partial demonstration of this rescue capability, the Saturn IB rocket and Apollo spacecraft for Skylab 3, the second crew to occupy the space station, rolled out to Launch Pad 39B on June 11, with the first crew still working aboard Skylab. Should the Skylab 2 crew have needed a rescue, workers at the launch pad would have modified the Apollo CM to accommodate five astronauts, installing two more crew couches underneath the standard three. Within about 25 days, Alan L. Bean and Jack R. Lousma, two of the Skylab 3 astronauts, would have flown the rescue mission, returning with Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz about five days later.

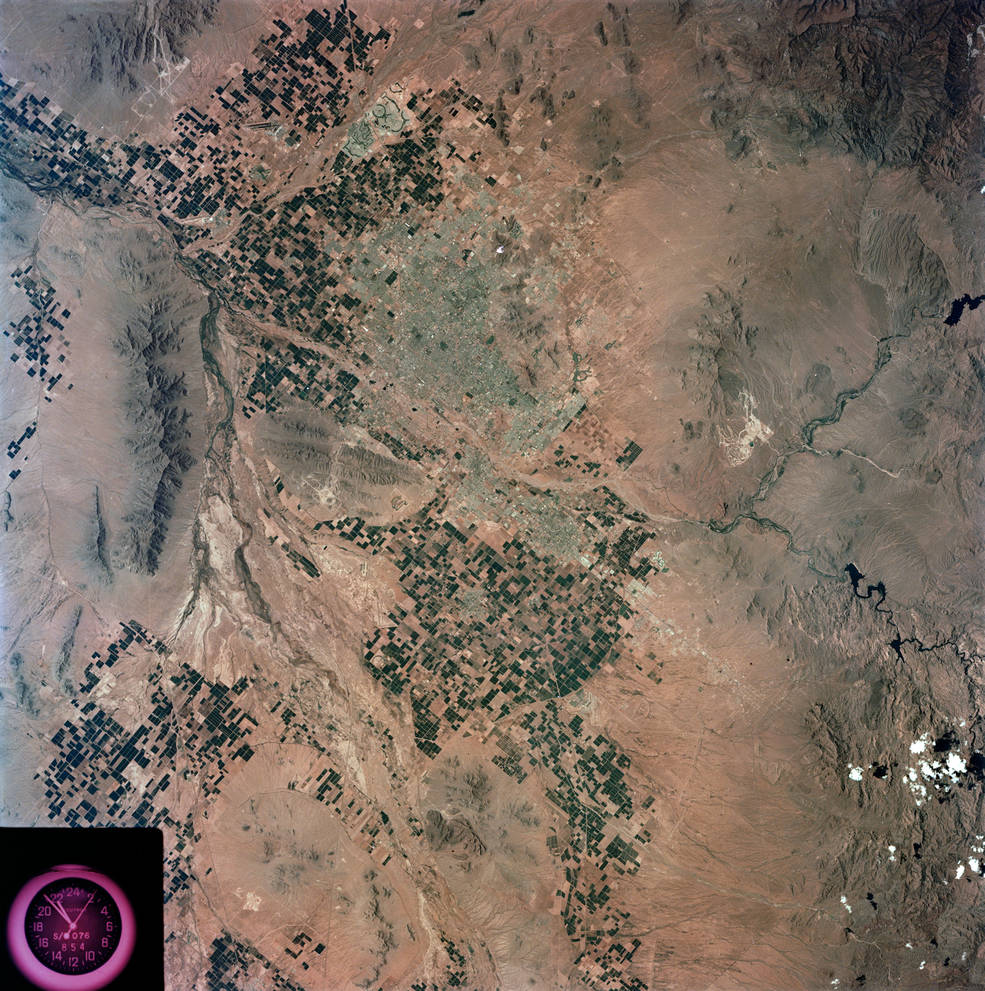

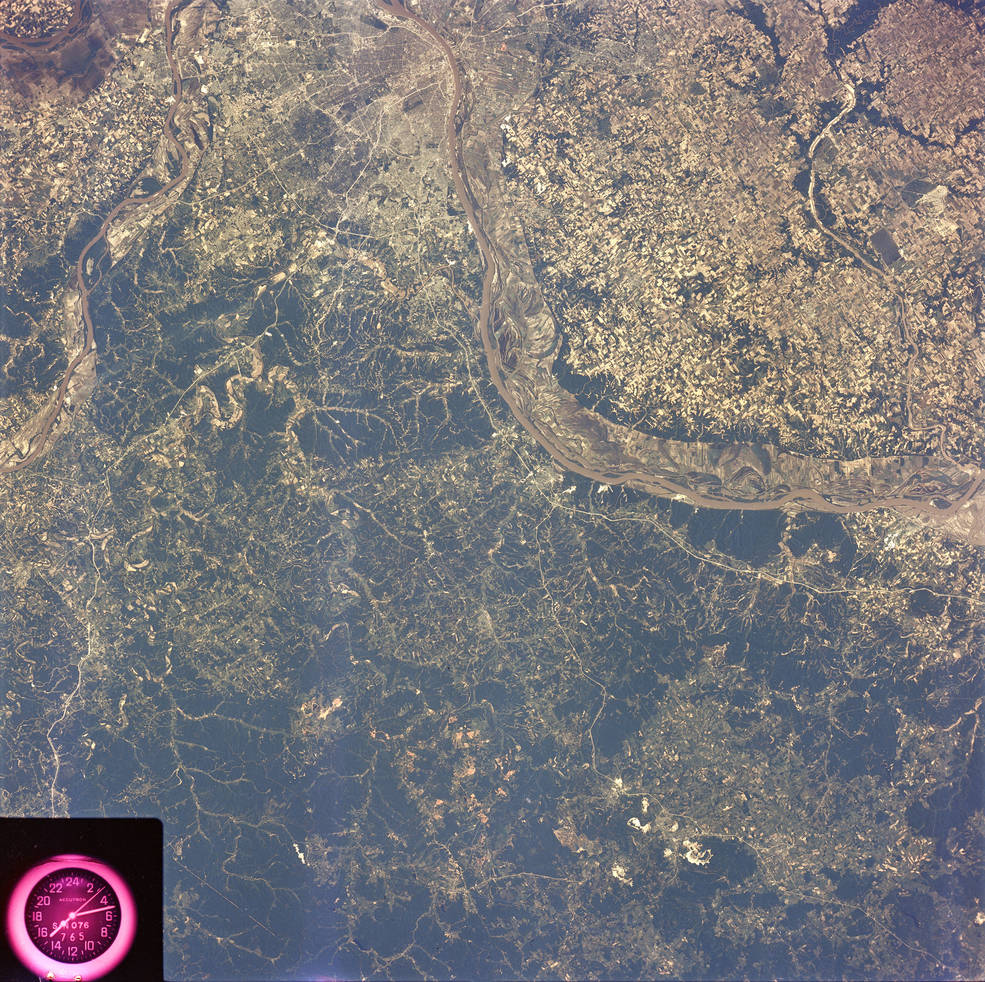

Three images from the Earth Resources Experiment Package. Left: Phoenix, Arizona. Middle: The Black Hills in South Dakota, with Rapid City at lower right. Right: St. Louis, Missouri, at top, and the Mississippi River.

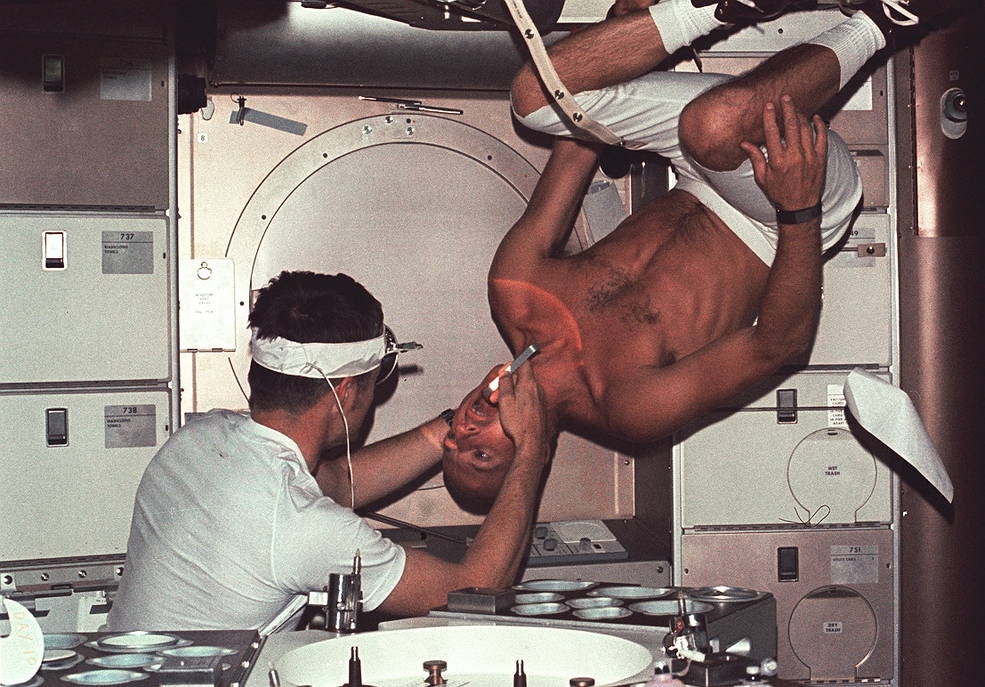

With power to spare from the now-deployed solar array, not only could the Skylab 2 astronauts enjoy hot coffee with their breakfast, but all the station’s experiments could be activated. The astronauts continued the medical studies critical to understanding their responses to long-duration spaceflight. On June 15, Weitz recorded the first solar flare of the mission using the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) instruments. The astronauts began in earnest to take photographs with the Earth Resources Experiment Package (EREP), as they improved their ability to find targets on the ground even through cloud dover. On June 18, they surpassed the mark of 23 days 18 hours 22 minutes for the longest human spaceflight, set by the Soyuz 11 crew two years earlier. The next day, Conrad and Weitz completed a spacewalk lasting one hour 36 minutes, bringing total spacewalk time for the mission to more than five hours, more than twice the planned duration. While the main goal of the spacewalk involved retrieving and replacing film for the ATM’s instruments, Conrad also brushed away some debris partially obstructing one of the instrument’s field of view and freed a stuck battery relay on a battery charger relay module by striking it with a hammer.

Left: Skylab 2 astronaut Paul J. Weitz takes fellow crew member Joseph P. Kerwin’s blood pressure for one of the medical experiments. Middle: Kerwin performs a dental exam on Charles “Pete” Conrad. Right: Weitz during the June 19 film retrieval spacewalk.

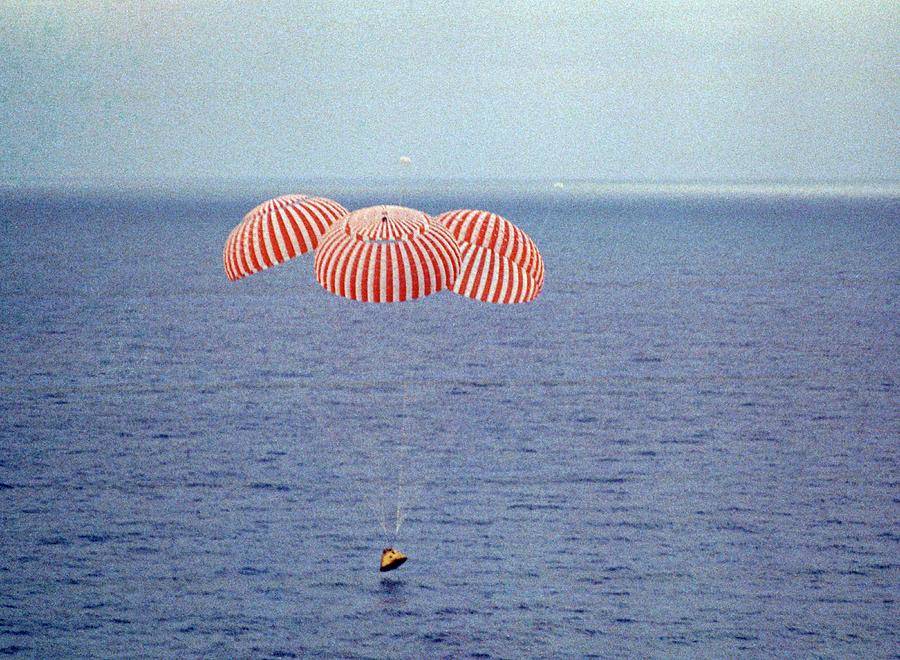

On June 22, the astronauts prepared Skylab for its uncrewed phase, readying it for the Skylab 3 crew’s arrival in late July. They stowed film and biological samples aboard the CM, put on their spacesuits, and closed the hatches to the space station. After undocking, Conrad flew around the station to document its condition, including the newly-deployed solar array and the slightly askew but highly effective parasol sunshade. Firing the spacecraft’s large Service Propulsion System engine twice, they began their descent back to Earth. Skylab 2 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 6.5 miles from the prime recovery ship, U.S.S. Ticonderoga (CVS-14), and 6.5 miles from the intended target 820 miles southwest of San Diego. Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz had established a new single spaceflight duration record of 28 days 50 minutes while they circled the globe 404 times, doubling the previous U.S. flight time record set by Gemini VII in December 1965. Conrad with his four missions now held the cumulative spaceflight time record of 49 days 3 hours 38 minutes, surpassing the previous mark held by James A. Lovell by 20 days. The Ticonderoga, on its final cruise, pulled up alongside the spacecraft. Sailors lifted the capsule with the crew aboard, depositing it on the elevator deck 39 minutes after splashdown. Recovery teams helped first Conrad, then Weitz, and finally Kerwin out of the spacecraft, and with assistance they walked down the red carpet to the Skylab Mobile Medical Laboratory, specially built trailers brought aboard the ship for this purpose, for postflight medical examinations. They talked with their wives on the telephone.

Left: The Skylab 2 crew undocks from the Skylab 1 space station. Middle: Photo taken during the post-undocking flyaround inspection shows the orange parasol and the deployed solar array. Right: Skylab 2 moments before splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

![]()

Left: The prime recovery ship U.S.S. Ticonderoga approaches the Skylab 2 Command Module (CM) as a recovery helicopter hovers nearby. Middle: Sailors lift the Skylab 2 CM aboard the Ticonderoga. Right: Skylab 2 astronauts Paul J. Weitz, left, Joseph P. Kerwin, and Charles “Pete” Conrad exit the Skylab 2 CM following their record-breaking 28-day mission.

The day after splashdown, the astronauts felt well enough to walk the deck of the Ticonderoga as it steamed toward San Diego. The following morning, off the California coast, the ship’s helicopter flew the astronauts to El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, from where a car drove them to the western White House in San Clemente, where President Richard M. Nixon hosted a summit with Soviet President Leonid I. Brezhnev. The astronauts presented mementos, hastily prepared aboard the Ticonderoga, of their flight to the two world leaders. They returned to the ship for medical tests before boarding a C-141 cargo jet for the flight to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, where they reunited with their wives.

Left: At the western White House in San Clemente, California, Skylab 2 astronauts (in white U.S. Navy uniforms) Paul J. Weitz, left, Charles “Pete” Conrad, and Joseph P. Kerwin present mementos of their mission to Soviet President Leonid I. Brezhnev, left, and President Richard M. Nixon. Right: At Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, Kerwin, left, addresses a crowd of well-wishers as fellow crew members Weitz and Conrad and their wives look on.

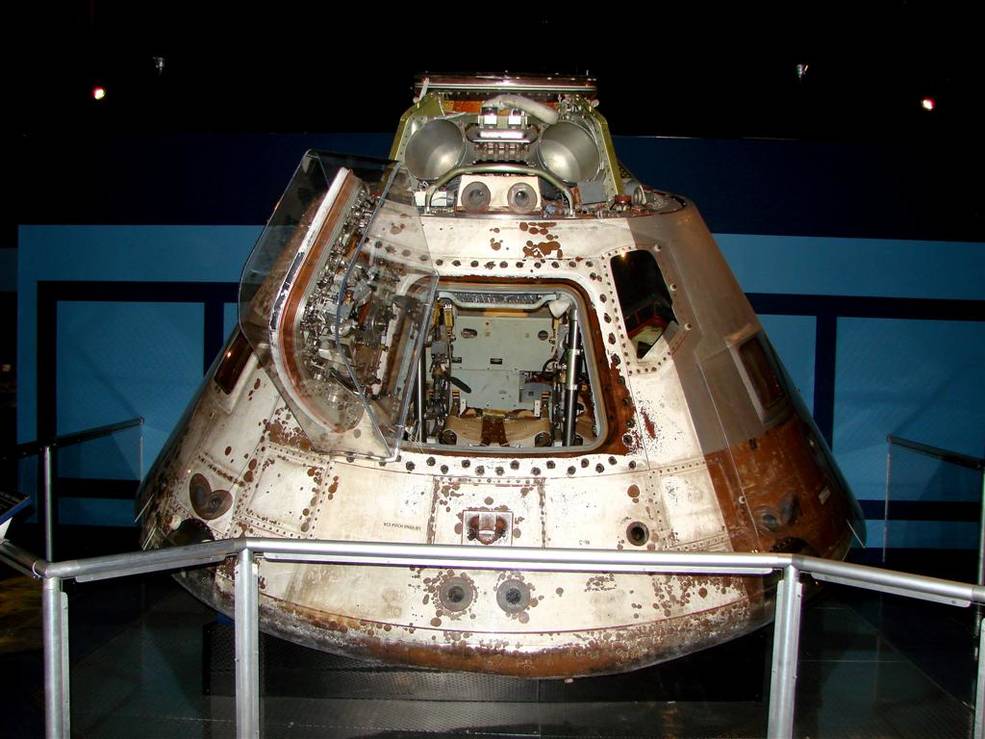

Three views of the Skylab 2 Command Module on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Image credits: Courtesy National Naval Aviation Museum.

By the end of the mission, Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz accumulated 397 hours of research time, completing 81% of the planned ATM solar observations, including nearly 29,000 images, 88% of the planned EREP studies, including more than 5,200 photographs, and more than 90% of the medical experiments. Their 28-ady stay demonstrated that not only could highly trained astronauts live and work productively in space, but they could overcome unforeseen problems. With the major repair tasks, they fully proved the need for astronauts in space and in doing so saved the Skylab program, enabling the next two even longer Skylab missions to proceed. Their example set the precedent for future programs to follow.

To be continued …

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center