Skylab, America’s first space station, launched on May 14, 1973, and immediately ran into serious trouble. During powered flight, aerodynamic forces tore off the station’s micrometeoroid shield that also served as a thermal shield. Debris from the lost shield jammed one of the large power-generating solar array panels, while the second one tore off the vehicle entirely. With an overheated and underpowered station, the entire Skylab program hung in the balance. NASA delayed the launch of the first crew, Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad, Pilot Paul J. Weitz, and Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin, by 10 days to allow managers and engineers to develop plans to save the station. Teams on the ground tested repair procedures and loaded the required tools into the Apollo spacecraft shortly before the crew’s launch. After a successful launch on May 25 and rendezvous with Skylab, the astronauts performed a fly-around inspection of the station, confirming the expected damage. During a standup spacewalk from the station-keeping Apollo spacecraft, the astronauts’ attempt to free the jammed array proved unsuccessful. After entering the station the next day, they deployed a parasol sunshade through a scientific airlock that brought internal temperatures down to comfortable levels, allowing them to begin their science experiments. But the lack of power from the missing and jammed solar arrays curtailed their activities.

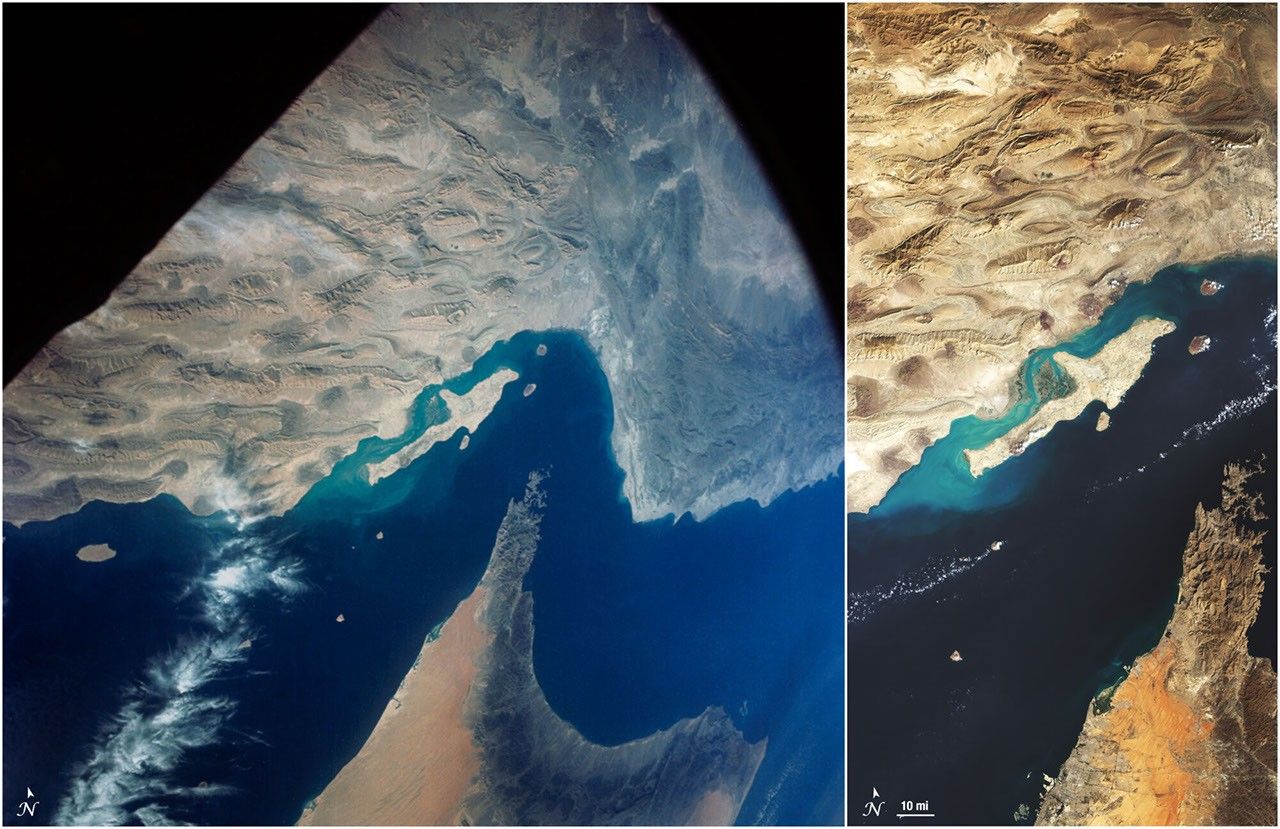

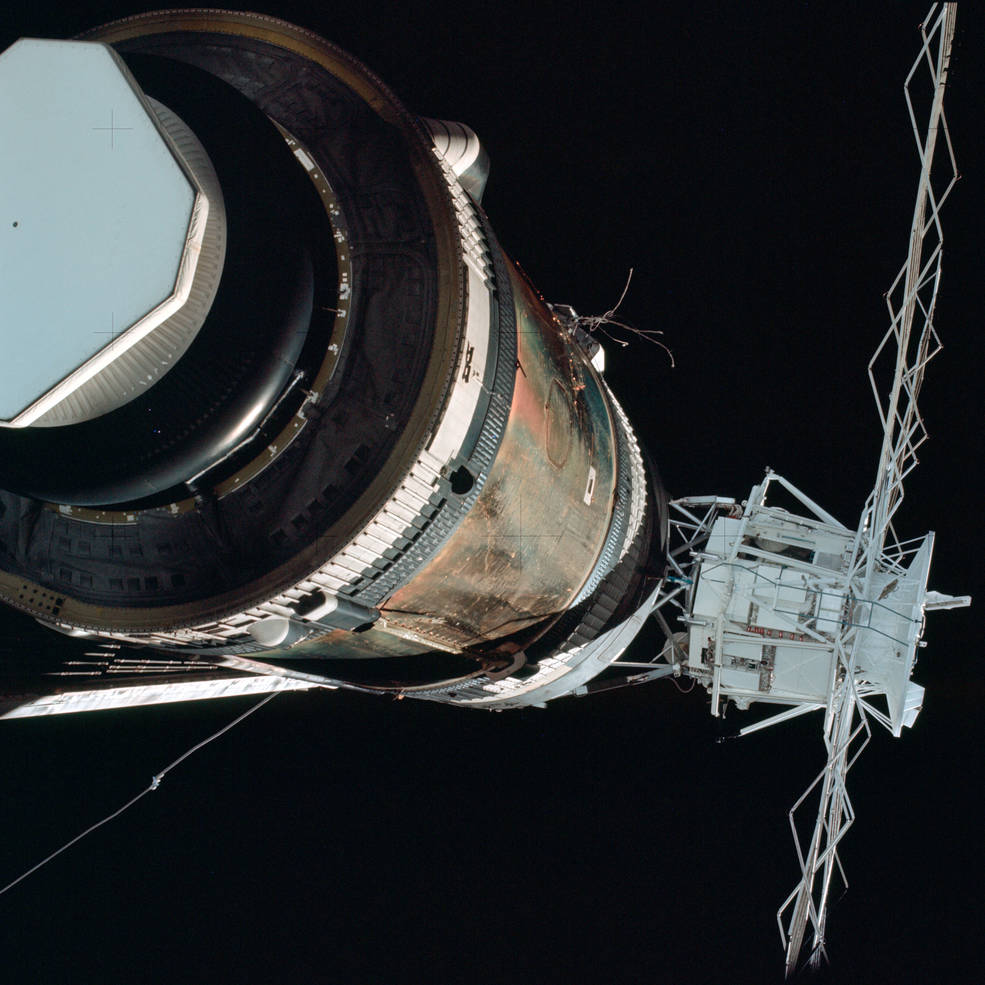

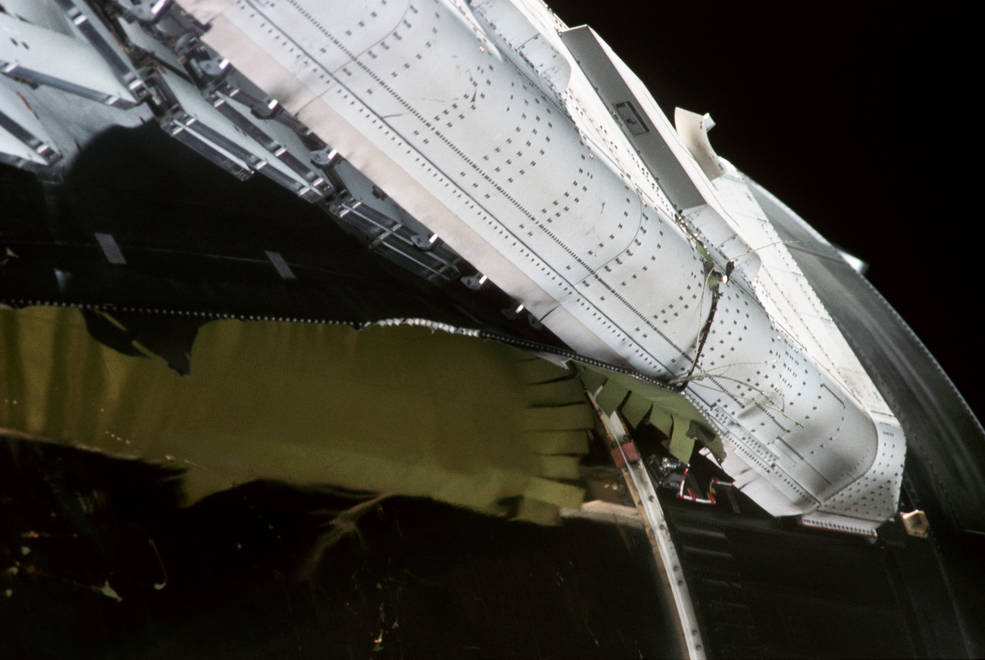

Left: Photo of Skylab taken during the Skylab 2 crew’s inspection fly-around, showing the missing micrometeoroid shield, the remains of the missing solar array wing (loose wiring at top) and the jammed solar array wing (at bottom). Right: Close-up of the debris of the micrometeoroid shield keeping the remaining solar array from opening.

Backup Skylab 2 Commander Russell L. Schweickart led a tiger team to develop various procedures for freeing the jammed solar array. Using the televised images, crew descriptions, and other available information about the nature of the debris, most likely a half-inch wide strap with a bolt embedded into the wing itself, engineers recreated the problem in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Wearing spacesuits in the NBS, Schweickart and Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson practiced techniques that involved using a cutting tool at the end of a long pole to cut the strap. Over several days, Schweickart described the procedures to the onboard crew.

Left: In the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Skylab 2 backup commander Russell L. Schweickart, right, and Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson develop procedures for freeing Skylab’s jammed solar array wing. Middle: In the NBS, Schweickart practices cutting through a metal strap jamming Skylab’s remaining solar array wing. Right: Another view of Schweickart in the NBS developing procedures for freeing the jammed array wing.

On June 7, 1973, their 14th day in space, all three astronauts donned their spacesuits. With Weitz in the Multiple Docking Adapter, Conrad and Kerwin depressurized Skylab’s Airlock Module. Conrad decided not to take any cameras outside to simplify an already complex spacewalk, so no photographs or film exist of the daring spacewalk except those taken by Weitz from inside the station. Conrad opened the airlock’s hatch and floated outside, with Kerwin beginning to assemble the five segments of the 25-foot pole with the cutter at one end, handing them out to Conrad. Kerwin anchored himself to Skylab’s structure and carefully grasped the metal strap with the cutter, making sure not to cut through it yet. The pole now served as a pathway for Conrad in a part of the station that did not have any handholds, since its designers had never envisioned any spacewalks taking place in this area. Using the pole, Conrad translated down the solar array wing past its hinge and anchored a rope to a vent module on the array beam, with Kerwin anchoring the rope’s other end to the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) truss structure. Kerwin closed the jaws of the cutter, severing the metal strap. With the offending strap no longer jamming the array beam, it opened a few degrees, but its frozen hinge where it attached to the station kept it from opening further. Both astronauts shimmied their suited bodies under the rope, moving to a standing position to exert tension to pull on the beam. Suddenly, the hinge gave way, the array beam opened to its full 90-degree deployed position, and with the tension on the rope released, sent both Conrad and Kerwin tumbling, their spacesuit tethers keeping them from floating away. With the beam deployed, its three solar panels began to unfurl, and Schweickart from Mission Control reported that the panels had begun generating power. The fix-it crew had saved Skylab in the first-ever repair spacewalk.

Left: The view of the jammed solar array wing as Conrad and Kerwin would have seen it at the start of their spacewalk – the astronauts actually took the photo on the mission’s first day during their flyaround inspection of the station. Right: In space, Skylab 2 astronauts Joseph P. Kerwin (left) and Charles “Pete” Conrad during the spacewalk to free the jammed solar array, photographed by Paul J. Weitz from inside Skylab’s Multiple Docking Adapter.

With the main task of their spacewalk successfully completed, Kerwin clambered up to the top of the ATM to inspect the instruments, open one jammed instrument cover, and replace film in one of the cameras. Spacewalks to the ATM constituted an integral part of Skylab spacewalking activities, therefore engineers had installed plenty of handholds and foot restraints, in contrast to the areas on the workshop near the solar array wings. Conrad and Kerwin climbed back inside Skylab’s airlock after 3 hours and 25 minutes, the longest Earth orbital spacewalk up to that time. That same day, the Skylab 2 crew surpassed the record for the longest American human spaceflight of 13 days, 18 hours, and 35 minutes, held since December 1965 by Gemini 7 astronauts Frank Borman and James A. Lovell. In the evening, they received congratulatory messages from President Richard M. Nixon and Vice President Spiro T. Agnew for their work in restoring power to Skylab, proving the utility of having trained astronauts in space. With adequate power restored, Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz successfully completed the second half of their record-breaking 28-day mission. The success of this repair spacewalk enabled NASA to plan with confidence the rest of the Skylab program that in terms of the amount and quality of research results obtained far exceeded preflight expectations.

Left: In the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, capsule communicator and backup Skylab 2 commander Russell L. Schweickart, right, and Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson react with joy at the news of the deployment of the jammed solar array wing. Right: The freed solar array is visible in this photo taken by the departing Skylab 2 crew who deployed it.

The solar array wing repair spacewalk endures as one of the lasting legacies of the Skylab program, demonstrating that a skilled and dedicated team and well-trained astronauts can overcome even the most challenging circumstances, restoring functionality to significantly damaged spacecraft. Managers and engineers in subsequent programs, including Salyut, Mir, the space shuttle, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the International Space Station, applied the lessons learned from Skylab’s repair activities to ensure continuing mission success.

To be continued …

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center