We’ll start by asking about your childhood, where you’re from, a little bit about your early years, your family, anything about your early education, or anything that gave you a sense that maybe you would like to pursue science as an avocation?

Sure. The question of where I’m from is always a hard one to answer — that alone is a 45-minute conversation! I was born in the Bahamas and lived there until I was 6. My folks got divorced and my mom and sister and I moved to Florida and lived there until I was 13. During that time, my grandparents had a place on a lake in Canada and I used to spend every summer there. I think the combination of growing up in the Bahamas and the time spent on the lake really gave me an affinity for nature. I had lots of time to explore, spending long days by the lake, swimming and poking around in the woods and that kind of thing. I think that was the beginning of my trajectory in science — I pursued a career in natural science, went into oceanography in fact. I think the interest in oceanography stems from being a water person fundamentally, from growing up around the water in the Bahamas, Florida, and Canada. When I was 12 my mom married an Army officer and, when I was 13, my family moved to Germany. I went to high school in a Department of Defense school there and met a chemistry teacher whom I keep in touch with to this day. He was very influential in my career path. Everyone’s brain clicks with something and mine clicked with chemistry. He was the person who made that happen. I took two chemistry classes in high school and became fully convinced by the time I was 16 or 17 that this was what I wanted to do with my career. I always knew I was interested in science and then sort of discovered chemistry and decided that was the thing for me. After high school I worked on a cruise ship for a year – more time spent on and in the water – and then went to college to pursue a degree in chemistry.

How about your parents? What did they do for a living and were there brothers and sisters in the family?

My dad was a musician, a jazz musician. My mom started as a secretary and worked her way into positions of increasing responsibility. And my step-dad, as I mentioned, was an Army officer. So there was not really any formal science in my background per se. I will say that during the time I spent with my grandparents, my grandfather was kind of a Mr. Wizard character — you know, he always had a way to explain the world around him. He also had a lot to do with my becoming a scientist, he really got me curious about the world and thinking about how the world works. I carried that curiosity into my academic path at the University of North Carolina, and it still carries me today.

Did you choose that university for any particular reason?

As funny as it may sound, the reason probably had more to do with watching Carolina basketball on television than it did with anything else. Being in Germany, there was no local point of reference for what U.S. universities were like and no ability to travel around and check out universities in order to help with decision-making. I had been in a national science competition when I was in high school and the finals were hosted in the triangle area of North Carolina. So I’d experienced the area that way and got to know a few people there. But a lot of it just came down to what things happened to stick in my consciousness, because of how relatively disconnected we were from everyday U.S. culture while we lived in Germany. And some of that was Carolina basketball; my step-dad loved college basketball and that was what we watched all the time. So that had a bit to do with it I would say. It turned out to be a good choice — I really loved the time there. I went into it as a chemistry major and I pursued chemistry throughout undergrad but in the middle of my freshman year, I decided to seek out an undergrad research experience. I was taking an intro to oceanography course at the time and the advisor I spoke with pushed the idea of research in oceanography. So I went and knocked on the door of the lab where I ultimately got my Ph.D. in oceanography! I sort of went into college convinced that I wanted to be a chemist and then I transitioned into wanting to be an oceanographer, but with a chemical perspective. You can have several perspectives with oceanography and mine was a chemical one. That experience of working in an inherently interdisciplinary natural science, where you really can’t constrain and understand every single thing about the system that you’re studying, maps really well to astrobiology. It’s very similar — it’s inherently interdisciplinary and you have to understand things as a system, some of whose components are unknown to you. In that respect, I think that oceanography is kind of a model for the way that astrobiology can be pursued.

Astrobiology is something of a new field and it correlates with about the time you got interested in it. You use the word with a degree of familiarity, but it was a new field when you got interested in it and how did that connection happen, that you discovered astrobiology?

Yeah, so the timelines correlate almost exactly, when I came to Ames and when astrobiology came to Ames in the form of an NAI team. Both of those things happened in the fall of 1998.

Let’s expand that to how you got from your educational life to starting your career at Ames.

I came to Ames not necessarily because I was specifically interested in space missions or whatever, although as a kid that was really an interest of mine. I loved going out with my grandfather and we would talk about the constellations and the stars and the moon, that kind of thing. The first science project I ever did in school was a report on Jupiter. When I was in fourth grade, that’s when Voyager was flying by Jupiter. And I wrote to NASA because you didn’t send emails at that time, you wrote letters, and I got back this manila envelope full of glossy pictures from Voyager II and I was kind of hooked. Now at Ames, some of my colleagues were actually associated with that mission and it just knocks me out that that’s true. But that wasn’t fundamentally my reason for coming to Ames. It was a couple of things: like so many people my wife and I had a two-body problem and we needed to find a place that worked for both of us. She’s in medicine and there was a lot that she could do around here, in sort of a trailing roll at that point, she had a lot of opportunities here.

How did you meet your wife? Was it in college or something like that?

We met in college. She’ll say that we met with me bumming a ride from her (laughs), but we were both chemistry majors and we had a lot of the same classes, and things just kind of took their course. As far as my coming to Ames, I always tell people who are looking for postdocs with me, that I think a postdoc can be any one of a number of things. It can be a chance to build new tools and add something completely new to your arsenal, maybe at the expense of flat out productivity, and on the other end of the spectrum, you can take what you know how to do well and just transpose it into a slightly different place or a slightly different question. I chose the former. Part of what I wanted to do was add stable isotope chemistry and analysis to my arsenal of tools. Dave Des Marais is one of the world’s experts in that and so I came to Ames to do a postdoc with Dave, to learn about isotope chemistry. It just so happened that that was exactly the time that Ames had just won one of the inaugural awards in the newly formed Astrobiology Institute, with Dave as the PI, and so it was sort of a natural thing for me to become involved with. I feel like Astrobiology and I sort of grew up together a little bit. Although the questions had been around in the field of exobiology and the research had been represented at Ames in the exobiology branch, a lot happened around that time in that field that made it grow and expand. So when I say that I grew up with astrobiology it’s because I arrived in the field at a time of great expansion. It really influenced the way that I thought. I brought a very interdisciplinary approach into it because of my work in oceanography and the way that astrobiology was being pursued was kind of resonant with that approach.

OK, we also ask about the most interesting work that you’ve done here at Ames and what you’re currently working on. Any discoveries, unexpected findings, or things like that?

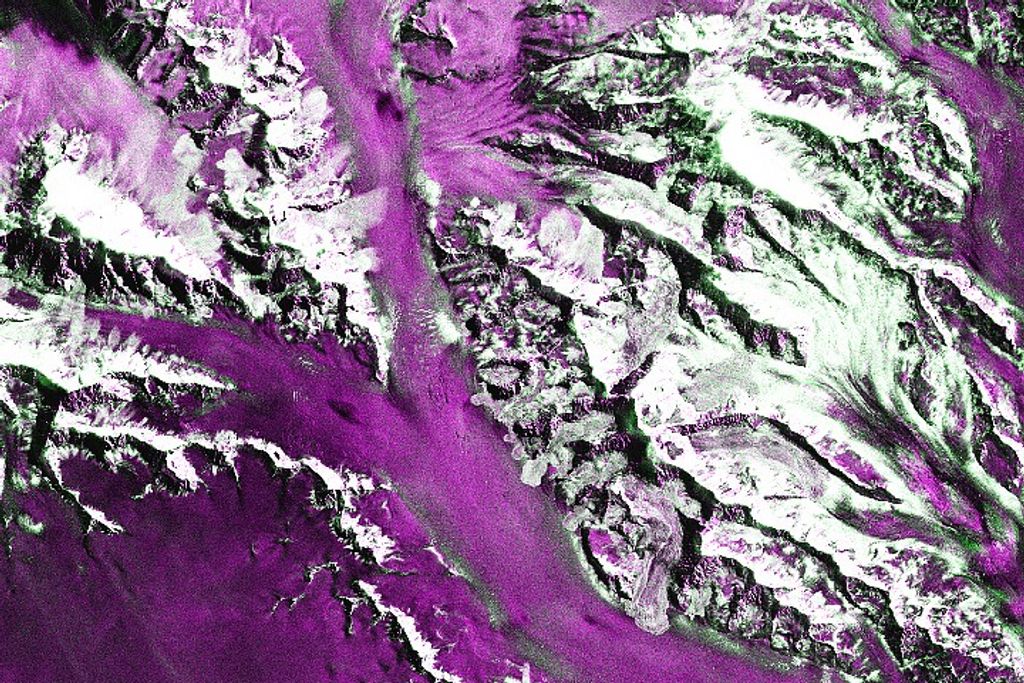

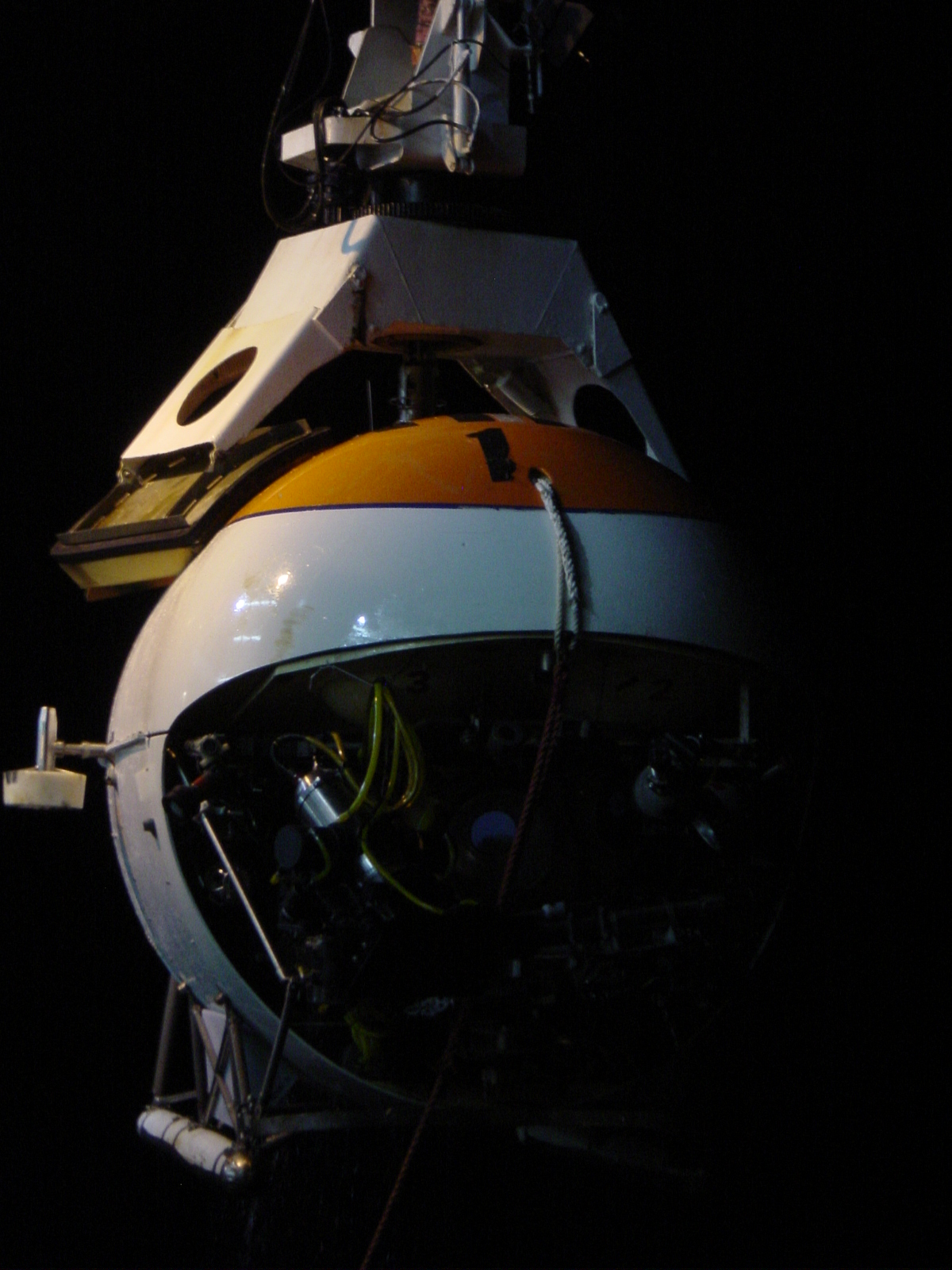

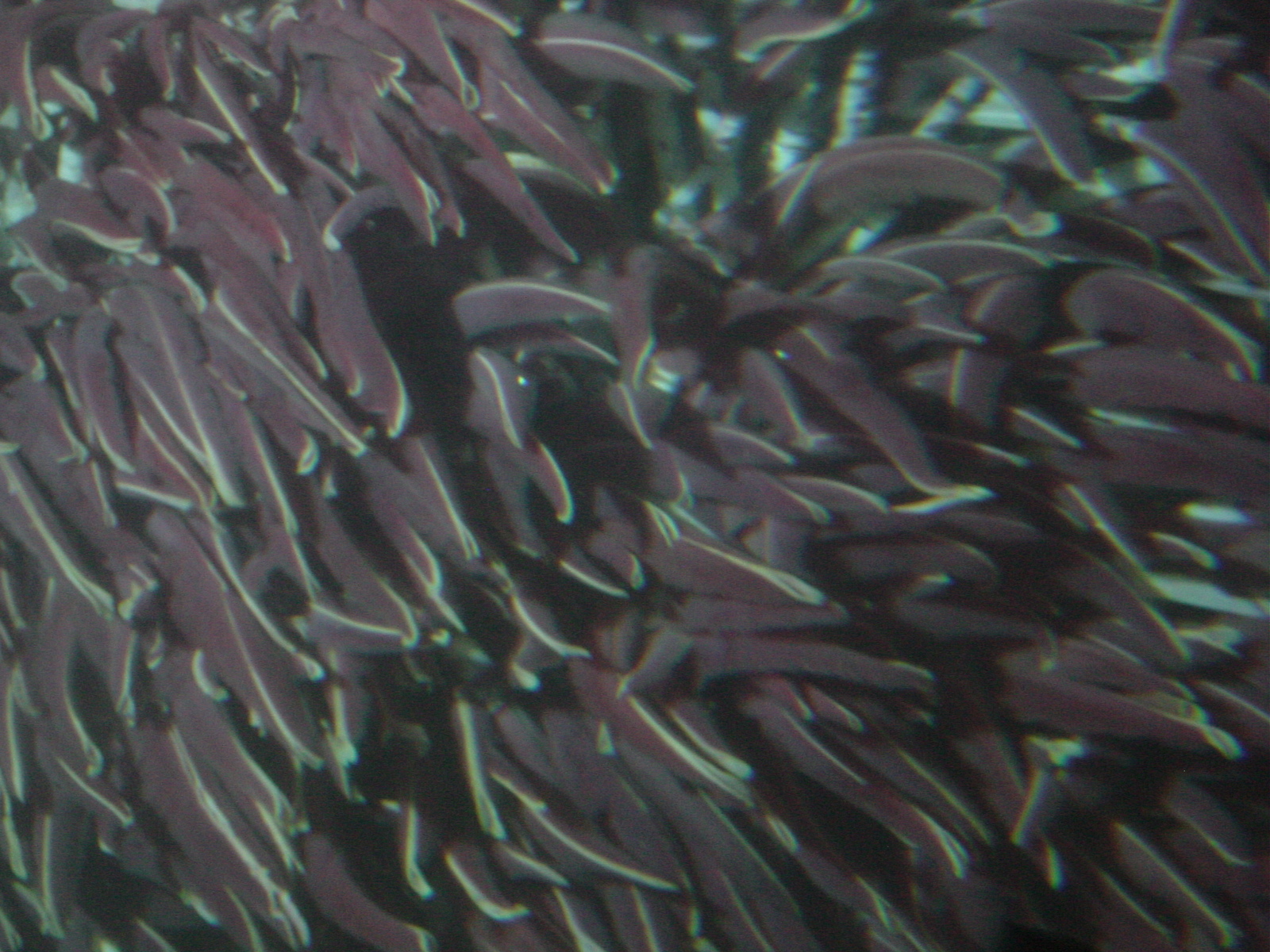

I think that for me the thing that really keeps me going in science is the connection back to the natural world. In my group, we try to do a balance of theoretical and fieldwork in seeking to understand environments beyond earth — taking principles that we learn here and using them to think about how life might play out in very different environmental contexts beyond earth. Ultimately for me, the fieldwork aspect is a chance to reconnect with my original motivation for being in the field, for coming into this area of science, which is curiosity about the natural world. The things that I would point to as exciting experiences are the opportunities to have gone to some unique places in our world, places that I don’t think I would’ve had any reason to go to, or any capacity to go to, if I were not a scientist. In 2003 I had the opportunity to go down to the bottom of the Sea of Cortez and dive on the hydrothermal vent field there, the Guaymas hydrothermal vent field. That cruise was part of an expedition to film an IMAX movie, the James Cameron film “Aliens of the Deep”. He made it possible for a number of scientists to go along for the ride and participate in the experience, and that was a fantastic opportunity for me. My undergrad and graduate work was done in a lab that did a lot of submersible diving and I was one of the few people in the lab whose project didn’t lend itself to that, so whereas many others had the opportunity to dive, I didn’t. Having the opportunity to dive at Guaymas was really exciting. It’s always a different experience to see something with your own eyes. I had seen movies of hydrothermal vents and the amazing communities that live there but it is a fundamentally different experience to look at it through the porthole of a submersible 2,000 meters underwater. Kind of like the difference between looking at planets in our solar system through a little backyard telescope versus seeing all of the beautiful glossy images that come from large telescopes. There’s something about the former, the fact that you’re seeing it with your own eyes, that makes it special. That same year I was able to go on an expedition to Spitsbergen, which is one of a cluster of islands about halfway between the north cape of Norway and the North Pole. In that expedition, we ultimately crossed 80° north as part of our cruise and that was a unique experience, it was just a gorgeous environment to work in. Part of it was done as an analog operation study, so a lot of the folks that ultimately wound up in the MSL project were there as part of that expedition. It was a great opportunity to be connected with the mission world. Both of those opportunities ultimately came my way because of Dave Blake, who was my branch chief at the time.

NASA has funded this research and so we ask you to comment on its importance in terms of NASA’s strategic vision and also its importance to the taxpayers, or humanity if you will, who are essentially paying the bills.

Let me start with the latter. I think it’s very worth asking the question: why are we spending public dollars on this when there are so many other places where we could be spending those dollars? I think, and it’s just my personal opinion, that part of what makes us who we are, what makes us human, is just an innate curiosity about things. To me, the questions that NASA is charged with addressing are some of the biggest questions that there are, some of the most fundamental aspects of our curiosity. You see that reflected in the public’s interest in what NASA does. One of the things that I’ve loved about working for NASA is that it creates so many opportunities for outreach with the public, and I feel that is an essential thing to do. It’s important that we tell people what we’re doing with their money and get them excited about it. That’s not a hard job because the NASA name, I think, draws people into conversation and gives you an opportunity to educate and excite. My sense from doing that is that people really are engaged and interested in these questions. So that’s the “why does it matter to the public” part. I could envision scenarios where you decide that there are more important things to do with the money spent on space science, but I hope we never reach the point where we have to give up that fundamental aspect of human curiosity. So why should NASA care about the work that I have been describing? A lot of my research has been to understand how life plays out in specific environmental contexts. I’ll mention one more field site in addition to the ones I described. Just last March, literally a few days before COVID shut us down, I returned from two weeks of fieldwork in Oman. The connection between Oman and the submersible work and the Spitsbergen work is that all of it relates to understanding how life plays out in a context that is fundamentally hosted by rocks. We live in an environment that is bathed in sunlight and that fact supplies our biosphere with hundreds of thousands to millions of times more biologically accessible energy than would seem possible in any of the other places in our solar system, or at least on Mars or any of the icy moons of the outer solar system. I think that unavoidably shapes our notion of what an inhabited world looks like and the ways that we might approach a search for evidence of life beyond Earth. The work in each of the places that I’ve described is meant to try to understand how life works when the context is very different — when the basic supply of resources, of energy and of elemental building blocks and of all the things life requires, flows from the rocky environment rather than from the sun and the products of photosynthesis. That’s the sort of context we think is applicable to places beyond earth where we are interested in looking for life. Almost all of those places that we think of as habitable are not habitable at the surface but rather in the subsurface. So it matters, I think, to find the places on earth that can represent those subsurface settings. It’s the attempt to inform the search for life beyond Earth that has taken me to such interesting spots.

That almost seems like the ultimate question that everybody, in one way or another, whatever they’re doing especially at NASA, wants the answer to that question, wants to find it in whatever way they can pursue, to try to validate and verify it. It is very consistent with other things that we have heard from other researchers.

I think that’s true. Ultimately life is so much a product of a system of interacting processes that almost everything that everybody does at NASA has a way of ultimately feeding into that question. It’s a really broad-spectrum thing.

It really is. So what is a typical day like for you, kind of bringing it down to the actual workaday world, and what do you like best and least about your job?

I can tell you what today was like for me: I think this is my seventh Zoom call! (laughs). A colleague of mine uses the term, ”Zoomed out”, as in, “I’m totally Zoomed out today”. I think we’re all sort of suffering from that. Bigger picture, I have a group right now of four or five people that I work with. A postdoc, a research associate, a very long-term lab manager, and a student intern. A lot of what I do is to try to support their various efforts – help generate ideas and funding, advise on research, help with writing things up. I touch base with all of them on a regular basis to see how they’re doing and how their work is going. One of the things that I love about my job is watching people take the baton and run with it, take the seed of an idea and be able to make something of it with skills that I don’t have. That’s the best kind of collaboration, where both parties bring different skills into it. I think that I’m a ‘big picture’ kind of person. I try to see the connectivity among things and that sometimes allows me to create the context for projects that then require more detailed efforts on the part of people who might well be more capable at it than I am. Bottom line is that I spend most of the time at my desk, either writing about work that’s been done, writing to propose new work to get done, and most interestingly, putting the experience gained into practice in a variety of NASA committees and mission-related stuff. I really do feel like that’s an important part of our job, not just knowledge creation but a synthesis of knowledge and ability to bring it to bear in big picture NASA decisions. All of that desk-jockeying means that I scarcely even know the code to my own lab anymore. It’s a little embarrassing, the number of times I’ve had to call the folks in my group and say “Can you tell me what the pin code is again?” (laughs)

Would you say that this current situation (COVID-19) has affected you very much or not really?

Yes and no. As I said, we try to do a balance of field, laboratory, and theoretical work, so we have shifted more towards an emphasis on the theoretical work and on taking the time to stop and write up what we can write up about the experimental and fieldwork. As things go on, ultimately the ability to write up experimental work will depend on the ability to be back in the lab. But there’s enough theoretical and conceptual stuff that is important to write up that we’re plenty busy for the moment. A couple of people that are working with me now happen to be very good with modeling, so we can make some decent progress on the theoretical work right now. We’ve fallen into a good routine of touching base with one another regularly, individually and as a group. I certainly miss the hallway conversations but our ability to sustain both the scientific dialogue and the personal interaction has held up pretty well. We have a virtual Friday happy hour every week. It’s something that we started just a few weeks into the shutdown. I wondered if it might last beyond a few weeks because in the first one or two we all had a lot to say and then by about the third one, nobody had gotten out and been able to do anything new so it felt like everybody was running out of things to say. But now six or seven months later we still meet every Friday and spend two hours talking with one another. It’s a great network to have and a way to support one another.

If you weren’t a NASA researcher have you ever thought about what your dream job might be?

I always would’ve said underwater photographer. I love diving, I love all things about the ocean. I don’t know that I have the skills to be an underwater photographer but any job that would have me in the water on a regular basis, trying to convey some sense of the wonder that I experience there and the beauty that I experience there, that I would see as my dream job. With national parks photographer being a close runner-up.

I can certainly understand the appeal of that! What advice would you give to a young person just starting out who would like to have the kind of career as a researcher that you have?

I think it’s important to come into it with the right motivation. The right motivation in my mind is that this is what really gets you up in the morning. It’s fundamentally about addressing your own curiosity about how things work. Often there’s enough other stuff that goes on in the context of this job that you need something like that. You need to re-capture your fundamental drive and curiosity about it. I often tell people who express an interest in astrobiology, because it really does seem to be a lure for a lot of folks just entering the field, that I think it matters a lot to ground yourself in one of the fundamental traditional scientific disciplines and then carry that fundamental basis into the more interdisciplinary field. That’s exactly how it plays out in oceanography. You come into it as a chemist or a physicist or a geologist, whatever, and then learn to add the other components. I think that strategy maps very well to astrobiology. And then just being willing to persevere, because the job is not without its challenges.

Well, you’ve talked a lot about your work, your career, your research, and so forth, but what do you do for fun?

When I have the ability, I love to be out in nature. I’m a very outdoorsy person. As I mentioned, I love to dive when I have the opportunity. We are fortunate to have a place up in the mountains, which is actually where I’m talking to you from right now. I love being here, I love being off in the woods or out on the lake. A lot of what I do is about the outdoors in one way or another. I also love to cook. Maybe that’s just the chemist in me. It seems to run in the male line of my family. My dad was a great cook and my son has recently taken an interest in cooking. For me, it’s a creative outlet. I think what’s fun about it is that so much of science is about precision and accuracy and whatnot, while cooking can be much more of a fly by the seat of your pants experience — you know, this seems like it belongs in there and a little bit of that would be good. I like the “witches brew” approach to things.

In your H. Julian Allen talk, you used your son as an example of entropy within your household. Did you want to say anything more about your children and your family? He was something like 6 in the example if I got that right?

He was 4 in the picture but that was years ago; he’s 15 now and is taking chemistry in high school. It’s a dangerous time for him because I want to be standing behind him saying “Oh, I know all about that, let me explain that to you”. I try to restrain myself but it’s hard! This also means he’s going to encounter the concept of entropy this year probably and will for the first time be able to understand the way I used him as an example of disorder and chaos! So my family: as I mentioned, we are a two-career family. My wife is an M.D. by training and now works in biotech, she works for a genomics company and my son is in high school. When it’s possible for him to be in the pool, he is a water polo player. Right now not so much, though!

It sounds like he’s got your genes though! From the chemistry to the water, the whole thing

He’s interesting. By and large, he’s a very cautious kid about most things but when he’s in the water that’s out the window! That does sound a bit like me!

I remember when my kids, I was better probably in math than other things in school, but when they brought their homework home when they were in high school, they were teaching it in a completely different way and I didn’t understand it and I couldn’t help them as much as I thought I could.

I’ve had that same experience. But fortunately, so far so good where it concerns the things that he’s brought home. Last year it was biology and algebra II. Biology is not my formal background but which I’ve had to learn a lot about it in my work, so I was OK with that one. But I can’t tell you how much algebra II I had to relearn in order to try to help him with his homework.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that is not science related?

I would say it’s a few things. I’m proud of my kid, he’s a good kid. I’m not sure if that’s really an accomplishment – I’m sure it’s got part to do with him and part to do with his environment, but hopefully, also something to do with his parents. Whatever part of that I may have contributed to, I’m proud of him. In terms of myself, I decided at one point that I was going to run an Olympic distance triathlon because that seemed like a big challenge to me. I’m not a fundamentally athletic person. I try to stay in shape and get exercise and that kind of thing but it struck me as a big challenge. Part of the reason I did it was because I was recovering from ACL reconstruction surgery, from a basketball injury, and I thought the way to show myself that I was back would be to train and run a triathlon. I think that sort of thing comes naturally to some people but, to me, 2 ½ hours of sustained high-level output was a big accomplishment. So I’m pretty proud of that as well.

How would you answer the question: who or what inspires you?

There are a few different things. I could talk about inspired in the sense of what inspired me to be in science in the first place. It was a great teacher and a grandfather who was fundamentally a huge part of my life and who was curious about the world. I try to carry that kind of inspiration into the way that I approach parenting, for example, or the way I approach outreach. My mom is pretty inspiring for having managed so well as a single parent with two young kids in a new country. I will say that recently I’ve been inspired by watching how people have responded to the adversity that’s come with COVID. I get this little daily newsletter that by and large, five or six days a week is all about all the terrible things that are going on in the world. But one day a week they reserve for only good things. Lately, there have been lots of stories about people who, in the face of all this adversity, have found ways to help others. People who have put their own concerns and their own misfortunes aside and dedicated their efforts to helping other people. I find that very inspiring.

Do you have any words to live by or some kind of inspiring or a favorite quote that we might find on your office wall that is particularly motivating or inspiring to you?

I had a quote in my dissertation: “Imagination is more important than knowledge”. I first encountered it in a fortune cookie in a restaurant in Chapel Hill but ultimately, it’s attributable to Albert Einstein. I look at that as a bit of a guide because I feel like there really is an important role for creativity and imagination in science, especially in what we do at NASA. The other one that’s always stuck with me, is Mark Twain had a book called “Innocents Abroad” which was about his travels on one of the first pleasure cruises taken to the Holy Land, what is now the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean. He starts the book by saying “Nothing is more fatal to prejudice than travel”*. I’ve been very fortunate to travel a lot in my life and I believe that’s true as well. When you have the opportunity to see that wherever you go, people are fundamentally the same — have the same concerns, face the same troubles, and have the same joys — it’s hard to maintain any level of prejudice in the face of that realization. So I think that’s a good one, too.

I think those are both good quotes and you’re a good example of both of them, as far as I can see. I can see the photo on your wall. Do you have pets?

My wife and I have always had dogs since we moved to California and into our own home where we could do that. We both grew up with dogs to some extent, had two that were with us for 14 years collectively, and we have two now. They are a very important part of our lives.

Do you live close enough to Ames that you’re saving a lot of commute time by sheltering in place or do you have a pretty short commute so it doesn’t affect you that much?

I bike to work most of the time, probably nine days out of ten. It’s about 4 miles from my house to Ames so it’s a 20-minute bike ride on most days. So I’m saving probably 40 minutes a day but I often get a lot of thinking done when I’m on my bike. It’s not the same as being in a car, with the concerns of traffic and that kind of thing. You still have to worry about it but time on the bike is thinking time for me.

I bike to work too and it’s about 6 miles for me so about 30 minutes and fortunately, I can use the Stevens Creek Trail which keeps me away from traffic. I actually feel guilty if I don’t bike because I keep thinking they built that for me because it’s about a half a mile from my house and about a half a mile from Ames, so it’s a very safe route.

Just for you!

Yes, just for me! Thank you for carving out this time for us and for speaking about your life and your career which has certainly been admirable.

Thanks for asking me. I think that you guys do a fantastic job with these and it has been very interesting to learn a little bit more deeply about my colleagues, even with people that I know well.

You’re welcome, Tori. Stay well!

[*]The actual quote is, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.”, which is way better than my version.