Editor’s note, May 13, 2024: This article has been updated to clarify the locations of the SERT II control centers and that Solar Electric Propulsion Technology Application Readiness (NSTAR) thrusters powered the Deep Space 1 and Dawn spacecraft.

“A genuine space success story,” is how Experiments Manager William Kerslake described NASA’s second Space Electric Rocket Test (SERT II), the first long-duration operation of ion thrusters in space. SERT II provided researchers with data for years beyond its expected lifetime and was a rare example of an entire mission – including the launch, propulsion system, spacecraft, and control center – being handled by one organization: NASA’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland (today, NASA Glenn).

The concept of electric propulsion thrusters dates back to the early 20th century, but because they must operate in a vacuum, there was no practical application for these systems until the space program decades later. In the late 1950s, researchers at NASA Lewis began investigating types of electric propulsion and analyzing missions that could use these systems. They produce low amounts of thrust by creating and accelerating small particles at high velocities, and over time, can accelerate spacecraft at very high rates of speed. Their ability to operate continuously for years at a time with little propellant makes them ideal for long-duration missions or keeping satellites in orbit.

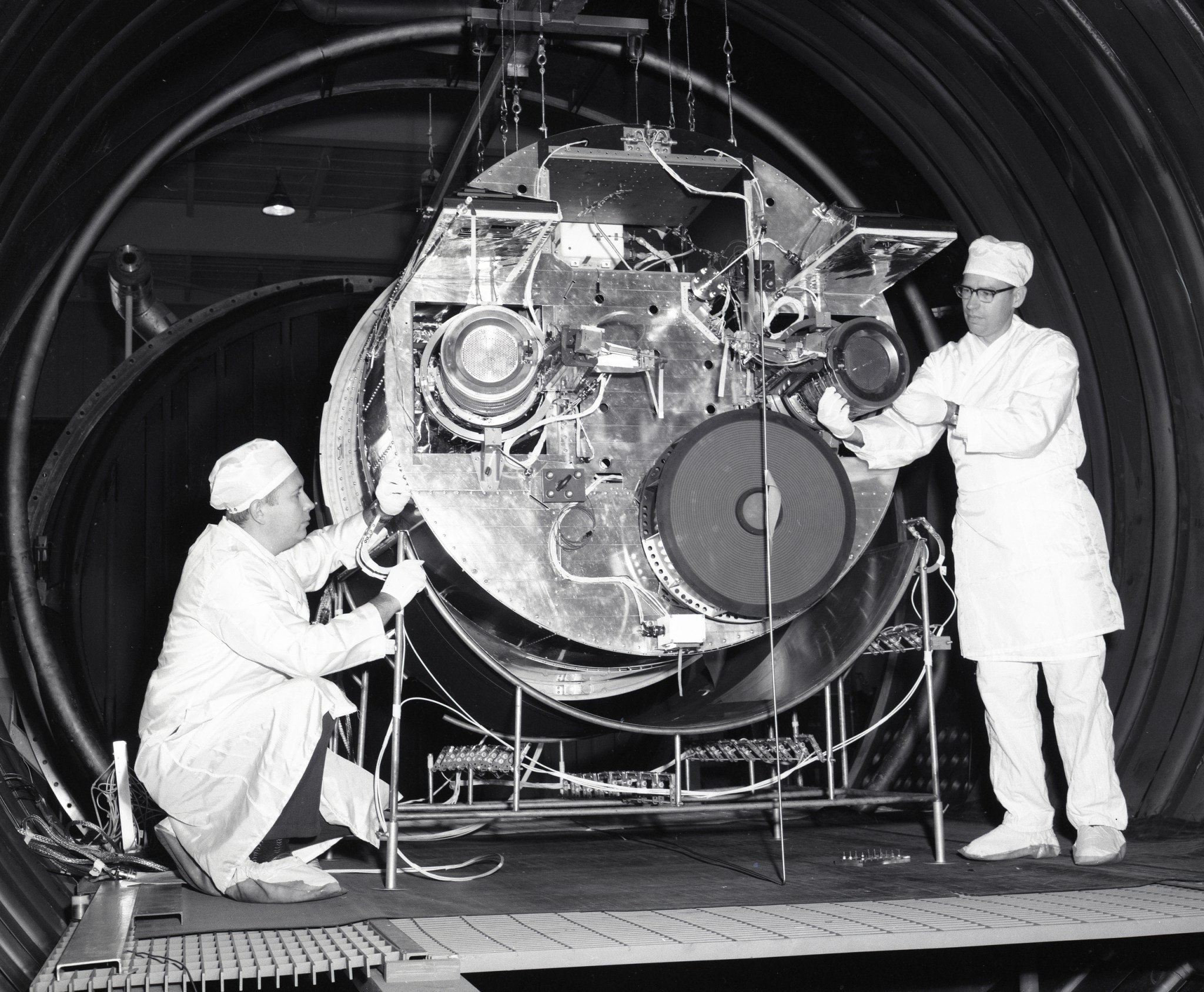

This work was expanded in the early 1960s with the creation of Lewis’ Electromagnetic Propulsion Division and the construction of large vacuum facilities, including the Electric Propulsion and Power Laboratory (EPPL). Lewis engineer Harold Kaufman’s electron bombardment ion engine, which used liquid mercury as its propellant, was the most promising option. While Kaufman’s thruster was undergoing extensive testing in the EPPL tanks, Lewis engineers began developing a spacecraft to test the thruster. During the 50-minute suborbital SERT I flight on July 20, 1964, the Kaufman thruster became the first ion engine to operate in space.

Lewis continued improving the thruster system, and in August 1966 received approval for SERT II. Researchers wanted to verify the thrusters could operate for longer durations in space, determine their effect on other spacecraft systems, and measure the degradation of solar arrays over time.

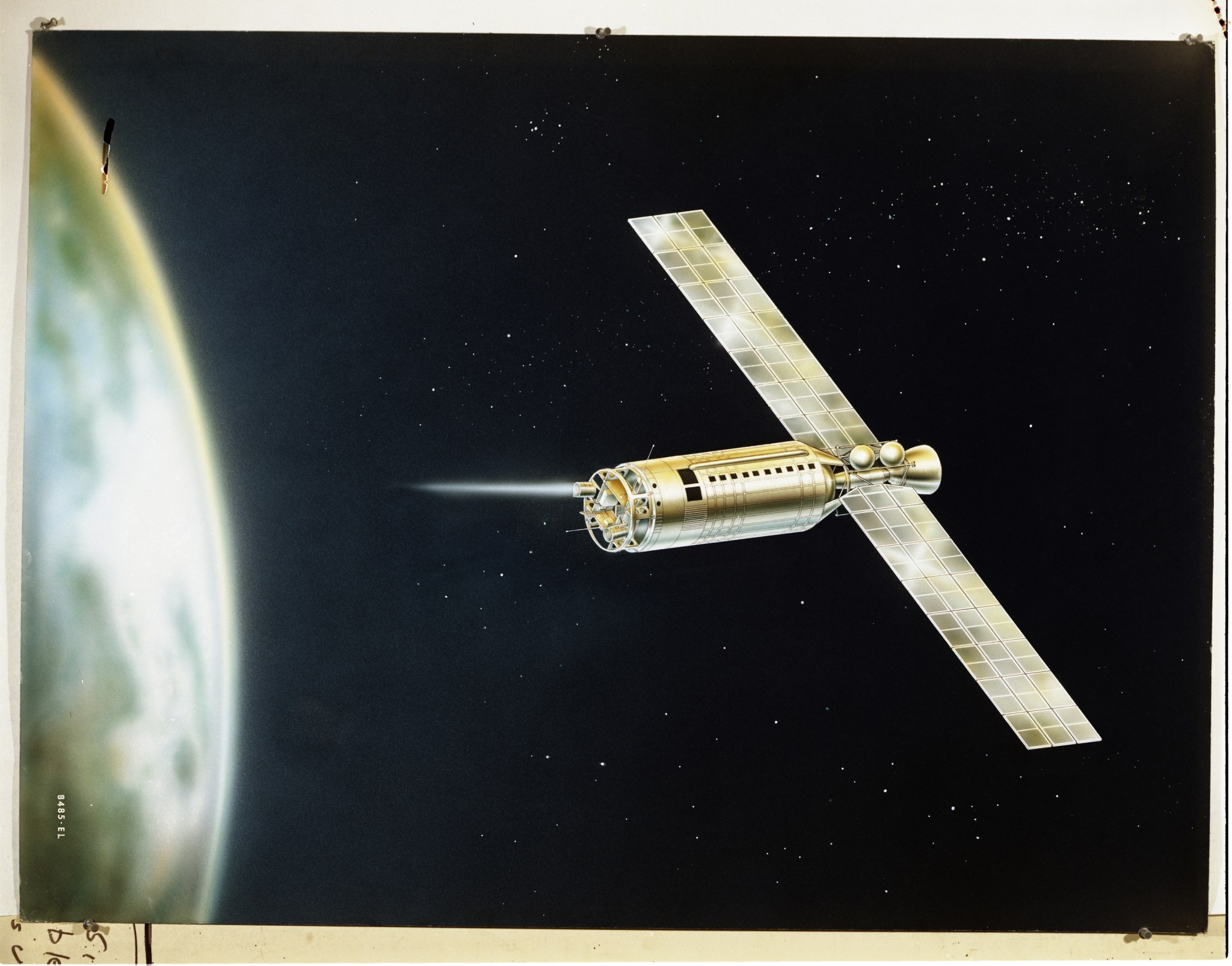

The center began simultaneous development of the SERT II ion thruster system and the spacecraft that would place it into orbit: a Thorad-Agena rocket. SERT II had two 15-centimeter diameter electron bombardment thrusters affixed to the back end and a 5-by-40 foot solar array, the largest ever flown by NASA at that time, at the other end.

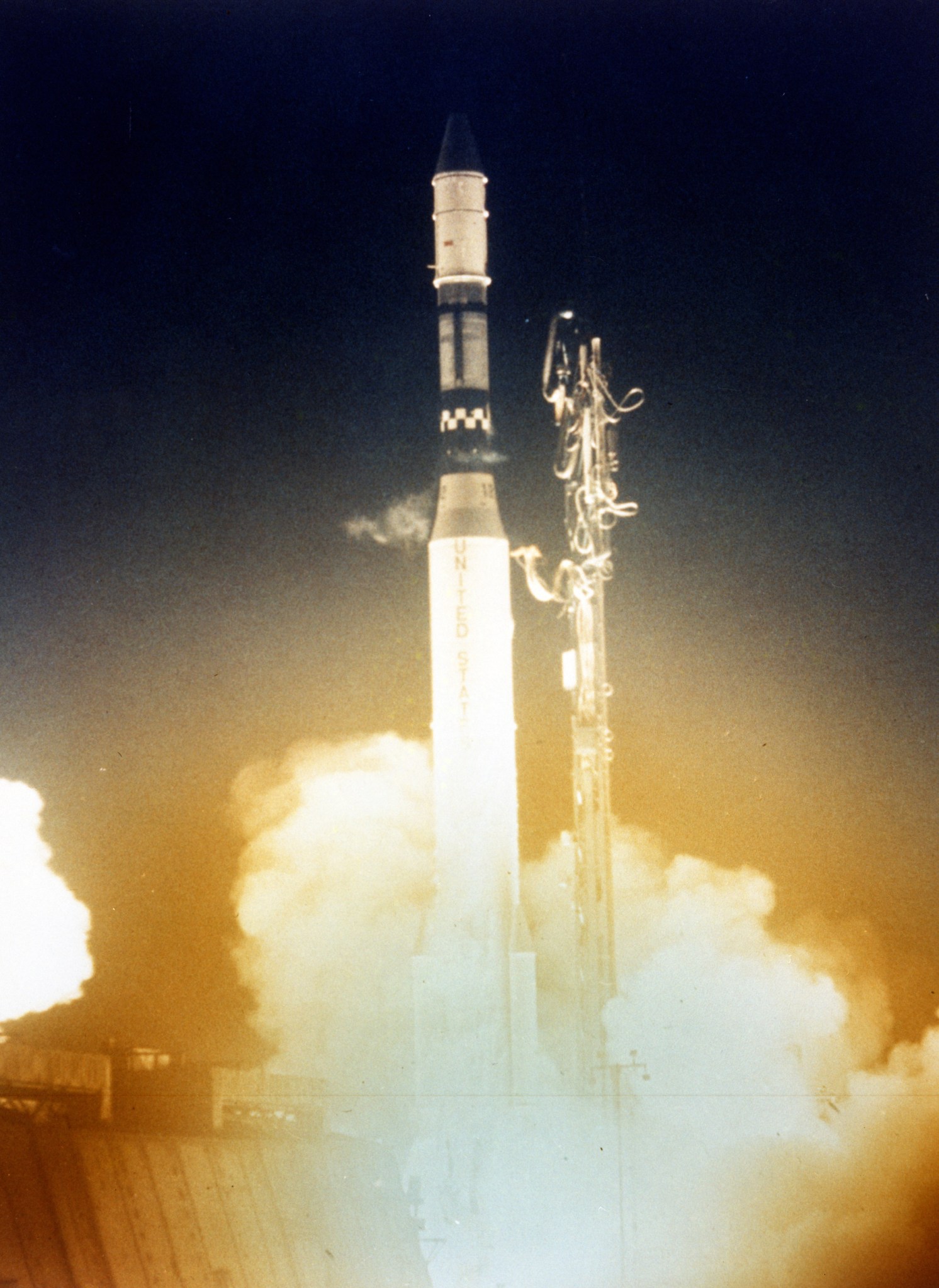

After a series of tests in the EPPL, SERT II blasted off on February 3, 1970. Project Manager Raymond Rulis called the launch “one of the smoothest operations I’ve seen.” SERT II was placed into a circular polar orbit that provided its solar arrays with the continuous sunlight required to power its thrusters and electronic systems.

On February 14, 1970, Lewis engineers activated the first thruster, beginning its six-month operational test. Three weeks later, operators shut the thruster down just before the vehicle passed through the path of a solar eclipse. It was restarted without issue afterwards and continued operation as the spacecraft encountered the eclipse a second time later that day.

The thruster operated successfully for five months until an electrical short in the grid caused it to fail on July 22, 1970. Two days later, the second thruster was activated. It operated smoothly for three-and-a-half months until a similar short occurred in mid-October. Though the SERT II thrusters failed to meet their six-month objectives, they did operate for extended periods, confirming data obtained in Lewis’ vacuum tanks.

The mission continued when Lewis engineers reactivated SERT II in 1973 to demonstrate cathode restarting, and the following year, they resolved an electrical short in one of the thrusters. During periods of intermittent sunlight, operators demonstrated restarting the thruster with less than an hour of power available. SERT II’s return to an orbit in continuous sunlight in 1979 provided Lewis researchers the opportunity to conduct over 500 restarts. They operated the thruster for 18,000 hours before the propellant ran out in the spring of 1981.

Over eleven years, SERT II provided data on hundreds of thruster restarts, restarts after shutdowns as long as 18 months, ion beam neutralization of one thruster by the other, and discovery of a new plasma thrust mode. SERT II also verified that thruster operation had no harmful impact on spacecraft and solar arrays.

Still, SERT II continued to be an asset to NASA researchers. In the late 1980s, Lewis engineers realized that an auxiliary experiment on SERT II that analyzed the effect of micrometeoroids on solar mirrors could be beneficial to research on solar dynamic systems to power space stations. During six months in sunlight in 1990, the Lewis team determined that after 20 years in orbit, there was no degradation of the solar mirror’s optical properties.

Many technological components of the SERT II thruster system were incorporated into subsequent generations of ion thrusters. By the time the mission was terminated, Lewis was already ground testing thrusters twice the size of those on SERT II. The center has continued to lead NASA’s electric propulsion efforts, developing an array of technologies, including the Solar Electric Propulsion Technology Application Readiness (NSTAR) thrusters that powered the Deep Space 1 and Dawn spacecraft. In support of the agency’s Artemis missions, NASA Glenn recently tested the thrusters that will power Gateway, NASA’s future lunar space station.

Additional Information: