Transcript

Host (Matthew Buffington): Welcome to NASA in Silicon Valley, Episode 63. With me again for the intro is Miss Abby Tabor. Welcome, Abby!

Abby Tabor:Hi Matt, thank you!

Host:Tell us a little about our guest today.

Abby Tabor:Okay, so today we’re talking with Chris Potter, who is one of these biologists by training, who didn’t know he could someday end up working at NASA. He studied ecology, and today he is an Earth Scientist at NASA Ames, and he’s been simulating global systems, Earth’s climate system, working on modeling that sort of thing. But also more recently he’s been looking at specific areas of the globe, and how are they changing more quickly than others. For example, he’s been up in Alaska. And he’s on the ground, out in the forests of Alaska, looking at how wildfires, which have gotten more intense and are burning hotter, are changing the landscape there. So he’s there, looking at how the permafrost is melting because the fires have burnt everything down to the surface. And he’s digging in the solid and taking thermal images and sticking probes in the ground to explore how the Earth is changing up there.

Host:Super relevant for today. We recorded this episode awhile back, but you know, speaking of all the crazy forest fires happening in Northern California, it’s all very relevant to what we’re living right now.

Abby Tabor:Really intense, yeah.

Host:So before we jump into the episode, a little bit of housekeeping. We would love to hear your comments about the podcast and ways we can improve things. We are on social media using the hashtag #NASASiliconValley. We also have a phone line you can now call in on, that’s (650) 604-1400. And a reminder, we are a NASA podcast, but we are not the only NASA podcast! Our friends over at Johnson Space Center have one called Houston We Have a Podcast, our friends over at Headquarters, and really it has content from all over the agency have one called This Week at NASA that’s both on YouTube, and also there’s an audio version, and we have a big RSS feed called NASA Casts where you can catch all of the NASA content in one big feed. We would love it if you guys leave us a review, we’re on iTunes, Google Play Music, SoundCloud, and we just started putting up audio versions on YouTube. Of course, the RSS feed, you can plug it into any podcast app and that all works. The reviews are really a cool way to help other people find the podcast. But, that’s enough of the housekeeping, but for today’s episode…

Abby Tabor: For today, let’s listen to Chris Potter.

[Music]

Host: How did you end up joining NASA? How did you end up in this area, in Silicon Valley?

Chris Potter: I joined NASA in 1991 as a NASA post-doc. There’s been a program here for a long time to bring new PhDs into NASA. I came out here to join one of the earth scientists who was working here, named Pam Matson. She’s since gone on to Stanford. She’s the Dean of Earth Science at Stanford, but she worked here.

I came here to work with her, and develop some computer simulation models of the earth system, which didn’t exist at the time. I had a background in the modeling of what we call the “terrestrial” part of the earth, the land surfaces, the ecosystems on land. And that’s what they wanted, so I came out here to fill that position and stayed. We just really liked it out here.

I had to commute from the city for a few years, but that was okay. We made it work. And then we eventually moved to the Silicon Valley.

Host: Did you do your post-doctoral work in earth science?

Chris Potter: Mm-hmm.

Host: When you were growing up as a kid, did you always have an eye focused towards wanting to work for NASA, dealing with space? How does all of that play into it?

Chris Potter: No, I didn’t ever think that I’d work for NASA when I was studying biology, which is what my background is in. All my degrees are in biology, and ecology in particular. But like a lot of people back then, I didn’t think NASA was the place to do that. I thought if I was going to work for the government, maybe I’d work for the Parks Service or the —

Host: Yeah, the Bureau of Land Management or something.

Chris Potter: Well, maybe not. I didn’t even know that they existed back then, because I grew up in the east. But, you know, the Environmental Protection Agency — something like that. As it turns out, NASA has the biggest environmental science budget of, arguably, any agency in the world. We are number one in terms of funding both basic research in earth sciences and in, of course, providing all the technology that it takes to get that job done: the satellites, the aircraft, the data systems, storage, which is a huge part of the whole endeavor at this point.

Host: It’s one of those things where it’s two-fold. One thing I always think of is: when you’re looking at exoplanets, if you’re looking at the other planets in our solar system, it’s really helpful to understand our own planet. We’re sitting on top of one big example of life that works and that exists, and if you’re out looking for life, if you don’t fundamentally understand what our own planet looks like, then how do you even know what you’re looking for?

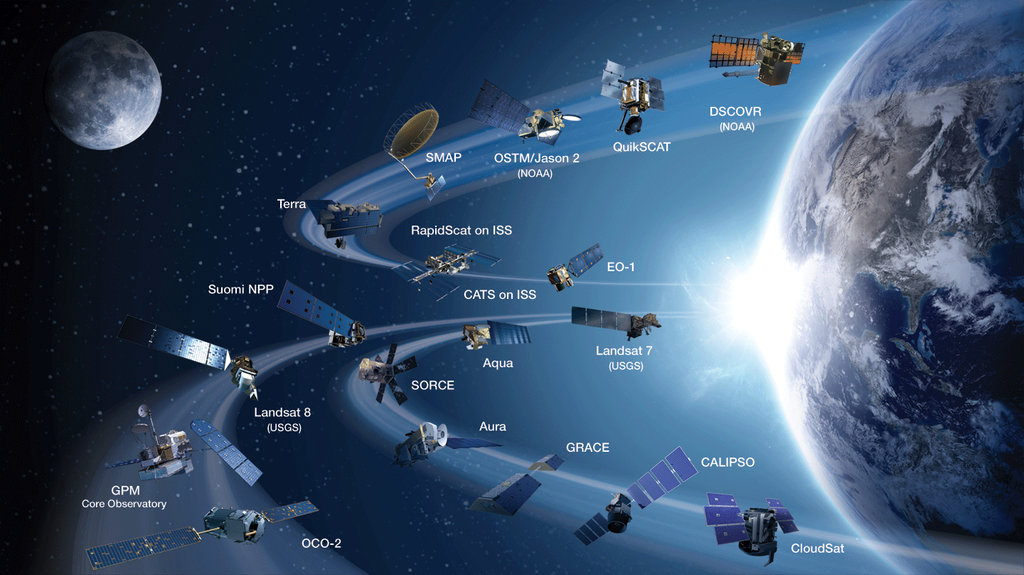

Also, on the flipside, a lot of the earth science stuff involves sending satellites up. There’s not a lot of government agencies that are particularity skilled in sending satellites up — I mean, obviously NASA and I’m sure the Air Force. But it’s one of those things where to put things in the air, it’s a very particular set of skills.

Chris Potter: Yeah, it is. NASA has been at it for a long time, and so has NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who are always close partners with NASA because they have the weather satellites. It’s not NASA’s job to forecast the weather or monitor the weather, but it is NASA’s role to look in the long-term. That’s the difference between weather and climate, of course. Climate is weather over hundreds of years.

And so that’s what we’re supposed to be doing. We’re supposed to be monitoring the long-term changes in the earth, and looking for new, undiscovered phenomenon that are going on with our climate system, or ocean chemistry, or land-use change patterns, in the same way we would be looking for them if we were looking at Mars. We’d be trying to discover something new, and then share that with the rest of the scientific community.

We’re certainly not alone as a space agency, too, there. All the developed countries in the world have large space agencies that are starting to rival NASA’s. The European Space Agency, the Brazilian Space Agency, the Chinese and the Indian Space Agencies all have satellites that are starting to rival ours. So we need to keep our game up.

But in the meantime, we can benefit from all the data they’re collecting as well, because as long as there’s sharing, open sharing of these satellite image datasets or measurements of the atmosphere, we can all benefit and push climate science, or any other sort of earth science, ahead for the benefit of. . . you know?

Host: The scientific community?

Chris Potter: Well, more practically, negotiating scientific treaties, treaties among nations, whether it has to do with the use of the oceans, the use of space, the use of the atmosphere, or greenhouse gas emission reductions, all of it. It’s our job as scientists, NASA scientists, to provide the best scientific information so the decision makers and politicians can make wise decisions that include the data.

Host: Going back a little bit, when you first came to Ames, when you first came to NASA, what exactly were you working on? Obviously something in earth science, but what was your day-to-day looking like?

Chris Potter: When we first got here, our role was to work with a team of scientists. Some were here at NASA Ames, and there were other key members at Stanford University and the Carnegie Institution of Washington there at Stanford, who is a leader in global change policy and science of all kinds, and also with Goddard Space Flight Center as a partner, and several other universities. We were working as a team to develop the first model, global model, of the earth surfaces and the greenhouse gas emissions that they were contributing to the atmosphere.

No one had ever developed one before. That was our challenge. We succeeded in a couple of years to develop that model, to publish the first paper that used NASA satellite data to make it much more authentic, true to the ground observations that we were collecting at the time, which were pretty rudimentary but compared to what we collect now. They were still very unique and stunning images of the earth.

We created what was called the first “Breathing Earth” model, and animated it. It even made a piece on CNN when it first came out.

Host: Oh, nice.

Chris Potter: Yeah, it must have been a slow news day.

Host: What is your day-to-day? What are you working on right now? I heard something along the lines of going to Alaska and having a bear gun, so talk to me a little bit about that.

Chris Potter: Well, we’re doing much advanced versions of the same things I did when I came here, but now we are using much, much more detailed satellite images and aircraft images of different parts of the world. While we’re still simulating the whole globe as a planet and a global system, more and more we’re trying to isolate specific areas of the world where we don’t have a good understanding of what’s going on there yet.

Alaska is one of those places. It’s warming much more quickly than our part of the world, the temperate or tropical areas. The ice under the soil and [in] the soil is melting very quickly. The lakes are not freezing over the way they used to even 20 years ago. If you ask any Alaskan, they’ll tell you, “It’s not like it used to be here. We are having trouble hunting, and fishing, and doing all the traditional things our ancestors used to do, because we don’t know every spring whether the ice will be frozen or thawing. And we might go right through the ice when we try to go out to our traditional hunting, fishing, and trapping grounds.”

So that’s why we’re there in Alaska, and NASA has a program that is funded through its Terrestrial Ecology Program in Washington. It’s part of the Earth Science Mission Directorate there. It’s called ABoVE. It stands for the Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability and Observation Experiment.

Host: Because of course there’s going to be an acronym for it.

Chris Potter: Of course, and “ABoVE” sounds pretty good. It’s sort of above the latitudes where we normally live and work, and it covers most of Alaska — well, all of Alaska and parts of Northern Canada, which are also experiencing rapid climate warming.

And so there are teams out there every summer. There are aircraft flying over the whole state right now, even as we speak, trying to understand what’s changing, where it’s changing, what the consequences are for both the atmospheric changes from greenhouse gas emissions that may be going up as a result of warming — that’s our hypothesis; that’s a working hypothesis — but also on the ground, there are vulnerabilities to larger and more intense, hotter fires, wild fires, there in the forest. As these areas burn, it changes the radiation budget of that area, and it may burn right down into the soil, and disrupt the permafrost, and cause the entire area to collapse in a big hole.

Host: Oh, wow. The permafrost, the ice crystals, the frozen. . . I mean, it’s propping it up. You know, when water freezes, it expands. It’s holding it. It’s stable.

Chris Potter: Right, yeah.

Host: If you get rid of that, you’re going to have a bad time.

Chris Potter: Yeah, it’s just like standing on top of a pond and having all the ice melt out from under you. There’s a thin layer of soil over the pond, but as soon as it collapses, you’re going to create a very liquid, slushy environment. And the trees collapse into it if they were on top of it, and so the whole system changes over night. That means that what you were using it for — in terms of either hunting, or trapping, or just recreation — you have to change your plan.

Beyond that, the atmosphere is loaded up with these greenhouse gases that were stored in the soil and the peat moss — there’s a lot of peat moss in most of these forested areas. That’s been stored there for tens of thousands of years, and now we are allowing it to come out during the fires — when I say “we,” that assumes, connecting the dots, that people are responsible for the greenhouse gas emissions, increasing greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere, that are warming the climate, that are causing more fires. That’s the chain of indirect effects that lead us back to the human nature of more intense and hotter wild fires throughout the whole West, from California, Southern California, all the way up to Alaska.

Host: Obviously you’ll be there on the ground. You mentioned the airplanes flying over. Is this a combination of all the different data points? I’m imagining — and tell me if I’m wrong — you have satellites that are taking some measurements as they can, as they end up passing over, but combining that data with airborne data, combining that with data you grab on the ground, and that all of those, with their powers combined, help paint a good mosaic of what’s going on.

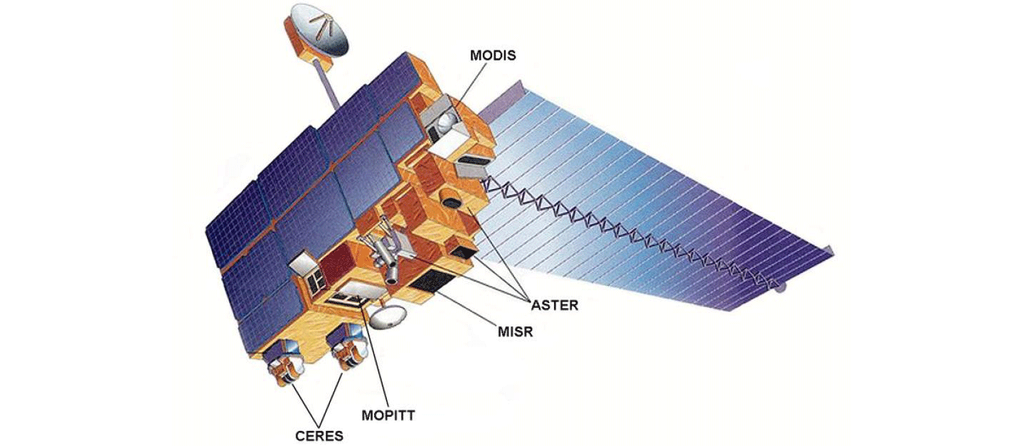

Chris Potter: Right, right. It’s basically scaling down from the satellite image, which NASA’s best image would give you a ground resolution data point that is about the size of a tennis court. That’s our best satellite for that. But airborne data can get you down to a few feet resolution on the ground, so you can start to see individual patches, and trees, and little ponds. And then, of course, right on the ground, we’ll measure it at a few centimeters resolution.

We want to put all the pieces together, and make sure — as we reassemble them from the ground, to the aircraft, to the satellite — that it all averages [out] again. That way, we much better understand what our satellite is giving us.

The satellite that we use for this study, for the most part, is the Landsat satellite. We’re on the eighth Landsat satellite since it was launched in the early 1970s. It’s considered a national asset, and is not subject to budget cuts. Pretty soon, we’ll launch Landsat 9, so there’s continuity in the program going forward, if anything happens to Landsat 8.

We’ve had over 30 years now of continuous observations every two weeks. The satellite goes over every two weeks, and gives us, hopefully, a clear image. In Alaska, it’s very cloudy at times, so we’re happy to get a clear image every month. That’s usually adequate for us to monitor, certainly from year-to-year, what has happened to the surfaces, and the forest cover, and the tundra cover, which is north of where I’m going to go. I’m going to the interior of Alaska, where the forests are being affected.

But north of there, the shrubs are really doing well. They’re growing into the tundra area, and making it even greener in those areas. So that’s changing the habitat for all kinds of wildlife.

Host: What does your day-to-day look like as you’re on the ground dealing with stuff?

Chris Potter: During this trip?

Host: Yeah, yeah. What do you have to prepare for? What do you anticipate?

Chris Potter: We need to get in our mode of transportation in the morning, and travel maybe five miles out from the town we’re staying in to get to an area that we can see, from the satellite imagery, had been burned. And there were large, large fires up there, unprecedentedly large and hot fires, in 2015. Now we’re two years after that.

And so we will go to those areas we can see on the satellite imagery that had different stages of the burns, barely burned versus burned to the ground and charred. We’ll sample in all these different places — sample the soils, sample the thermal signature with thermal cameras — and take probes and put them into the ground, and then, in bags, take samples of the soil itself back to measure the carbon in the soil. And then we’ll go to the next site, and we’ll just keep doing this over and over again until we get a statistically large enough dataset to compare to the satellite and airborne imagery.

Host: What is your timeline looking like? So breaking the fourth wall a little bit. . . Right now, we’re in the middle of July. Is a trip happening in September?

Chris Potter: No, it’s happening in a week.

Host: Oh, it happens in a week. But you’re later on anticipating getting results, getting things, coming in, and writing papers, or however that works out?

Chris Potter: Absolutely, yeah. I’ve designed this one so that we can collect most of the data, 90 percent of it, there right in the field, write it down or have it in our digital devices. And then I’ll just immediately download it back to my computer that night, and put it all on a flash drive to bring back. But if the soil samples take a little bit longer, we’ll have to transport them back here, and they’ll be analyzed in a month.

So by January, when there’s the next big team meeting of this ABoVE project, we’ll take the results there, present it to our colleagues, be writing the papers, sharing all the results, and comparing with other folks’ perspectives and findings on the same kind of topics. There are working groups on fire, on carbon, on animal movement. It’s a big project. It involves many universities across the country and in Alaska.

Host: I anticipate that we’ll release this episode in the future, so people are hearing us from the past. By the time this airs, you will have already come back from your trip, and started working on some of that data and some of those results.

Chris Potter: Sure, we’ll be working on the data for the next couple of months after I get back. It should go quickly, because we’ve set it all up for over a year now, and we know exactly how we’re going to plug it into our plan and our formulas. We need to have it ready by the end of the year for a presentation to scientific conferences.

We still publish papers in scientific journals. That is one of the main ways we get evaluated as scientists still at NASA. Even though those journals are all digital and online, we still have to go through the “peer review process” we call it, and pass muster with our colleagues, and get their comments, and feedback, and improvements on what we’re doing. That’ll happen in the next couple of months.

Host: Talk about the different groups that you have to work with to do something like this. I’m imagining there’s the Bureau of Land Management. There is probably Alaska’s government. Are there other groups, other things? Is this an interagency thing that you’re working with?

Chris Potter: Yeah, ABoVE is all across Alaska, and it’s even into Canada. You have to work with Canadian agencies as well, to some degree. But in Alaska, the players are the Department of Interior, which includes the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land Management. There are scientists from US Geological Survey in Alaska who are very experienced and who we collaborate with.

And then there are local and tribal lands that we work on. I’m going to be working mostly on local lands and those that are used by the tribal, native people in Alaska. They are very important to — maybe the most important people to bring into this whole discussion, because they are the ones impacted and using Alaskan wildlife, fisheries, and are very dependent on the energy resources coming from all Alaska. They’re also vulnerable to the destruction or alteration of the infrastructure for pipelines, and shipping, and all of the things that we need to get energy resources out of Alaska.

Before I ever went, the first call I made on this trip was to the tribal leaders in the town where I was going to, because I wanted to make sure that they were up front in understanding what we’re doing and involved.

Host: Excellent. So talking about the interagency stuff, I’d imagine that’s not just for this Alaska trip. You guys work with them on a regular basis, especially here in California. Is there any other stuff that’s going on as well?

Chris Potter: Yeah, some really interesting interagency agreements we have in place for research have developed over years and years of discussions and collaboration. The one that I’m leading and spend most of my time on is with the Bureau of Land Management, which is in the Department of Interior. They own or are responsible for vast lands in Southern California and throughout the desertous Southwest.

There are places in the Mojave Desert, in what’s called the Sonoran Desert, or the Lower Colorado Desert, in Riverside County and Imperial County, where their lands have been used in the past for activities such as off-road vehicle usage, recreation, hiking, campgrounds, and that sort of thing — and grazing, of course, by cattle.

But most recently, at the urging of the state of California and Governor Brown, they have struck a deal with the energy companies in Southern California, PG&E, and also with environmental groups across the state, who are very much devoted to preserving the desert as a pristine ecosystem and the endangered species that live there, such as desert tortoises, and other birds, and amphibians. It’s called the DRECP.

It was a landmark agreement between the government and the conversation and energy corporations to lease federal lands for solar energy development. The governor had a very ambitious goal of meeting 20 to 30 percent of our electricity needs as a state in the next decade through solar and wind energy. What was to be developed were these large solar farms, photovoltaic or mirror-based farms that would. . . We call them “farms.” They’re over many, many acres out in the desert. They produce solar energy that’s transported mainly back to the Los Angeles area and San Diego counties.

They are operational. There have been several big ones built on BLM lands over the last few years. It’s our job, in cooperation with BLM — we’ve been brought in by them, “invited” if you will — to use our remote sensing satellite imagery to monitor whether those solar energy developments are having any negative impacts on the desert environment, because that was part of the deal that was cut.

BLM had to assure that they could find any early evidence and monitor any adverse impacts to endangered species, to air quality — because dust is a big problem there when you go up and down the roads – and install anything new in the desert, any disturbance to the fragile soil surfaces there, or desert biological crust that you can barely see but are very important for stabilizing the surface. There are ancient desert pavements that have been there since before humans were here. And they need to be preserved.

We are monitoring it month-by-month with, again, with our Landsat satellite and other airborne resources we have at our disposal to help the BLM demonstrate whether there are or have been any adverse changes. So far, we don’t see many, which is really good news, because I think we can have solar energy coexist with — [background noise] — a pristine desert. Whoops, that was my phone.

Host: Forget it. We’ll leave it in.

Chris Potter: So this energy development can be environmentally friendly. It can be environmentally monitored. We’re pretty sure at this point, without tracking every tortoise out there, that their habitat is not being adversely impacted. You do see the solar energy developments. You can see them from Google Earth. You can see them because they’re very large. You can see them from, of course, our satellite imagery. Or if you’re standing out there hiking across your desert campground, you might see them in the distance.

They actually cool the desert surface more than the natural vegetation even does, because they’re designed to absorb the high-energy, visible radiation. And so they’re turning that visible radiation into energy rather than re-radiating it back into the atmosphere, the troposphere. So they are cooling the desert surface, and may even provide refuges and habitats for animals that may otherwise not be able to find a cool place to hang out.

Host: To step into the shade. . .

Chris Potter: Right. They are fenced off, though, from most large animals, but smaller ones could crawl through and find some shade in there. You know, they probably won’t be there forever. They can be removed, unlike a coal mine or fracking for natural gas. Their long-term impacts on the environment will be negligible, because they can always be taken right back out.

We’re also estimating how long it takes for the desert to recover completely from any sort of small disturbance like this. Generally, when a transmission line has been built through Southern California desert, within about five years all of the plants and vegetation around those lines have grown back in. So we’re pretty confident that it’s still a resilient ecosystem to minor disturbances like solar development.

Host: Excellent. For folks who are listening, if you have any questions for Chris, we are on Twitter @NASAAmes. We are using the hashtag #NASASiliconValley. Sends us some questions on over. We’ll hook them back over to Chris.

Thanks for coming. This has been fun.

Chris Potter: Yes, it was my pleasure.

[End]