From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 412, NASA leaders Joel Montalbano and Ryan Landon reflect on 25 years of continuous human presence aboard the International Space Station, the milestones that shaped its legacy, and how international cooperation has been essential to the station’s success. This episode was recorded December 15, 2025.

Transcript

Kenna Pell

Houston, We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 412: Around the World for 25 Years. I’m Kenna Pell, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more.

For 25 years, humans have continuously lived and worked aboard the International Space Station, transforming it from a vision on paper into a hub of international collaboration, cutting edge science, and a gateway to the future of exploration. This remarkable achievement represents the dedication of thousands of people across the globe who’ve worked together to make low Earth orbit humanity’s permanent home. Today, we’re joined by two people who have been deeply connected to that journey, Joel Montalbano, NASA’s Deputy Associate Administrator for the Space Operations Mission Directorate, and Ryan Landon, Manager of the Research Integration Office here at Johnson Space Center as part of the International Space Station Program.

Both have been instrumental in shaping the station’s evolution, Joel through his leadership and operations and partnership, and Ryan through her work, driving groundbreaking science aboard the orbiting laboratory. We’ll reflect on their early experiences with the space station, explore the milestones that have defined the past 25 years, and look ahead to how the station will continue to prepare us for the return to the moon through Artemis and eventually humanity’s first steps on Mars.

Let’s get started.

<Intro Music>

Kenna Pell

Welcome to Houston We Have a Podcast Ryan and welcome back Joel, you are no stranger to the podcast. You were on a few but one similar to this topic on episode 169 It was released on the 20th anniversary of International Space Station, continuous human presence on November 2 of 2020, and I listened to it today, and at the end, you said that you were ready to come back anytime. So glad you’re here again. Now, when you were on here last, you were the ISS Program Manager, and now you’re NASA’s Deputy Associate Administrator for the Space Operations Mission Directorate. Can you tell us what that means and how your work relates to space station.

Joel Montalbano

Okay, well, first of all, thanks for having me back. I tell people that we have some of the coolest jobs in the world, working for NASA and working on human space flight and everything associated with that. As the NASA Deputy Associate Administrator for Space Operations, that includes the International Space Station Program, the Commercial Crew Program, the Launch Services Program, the rocket propulsion testing done at Stennis, the NASA Deep Space Network and the Near Space Network. So the TDRSS satellites, and then all our Deep Space Network, Human Research Program, the commercial LEO, and then space sustainability, which is a newer activity that we’ve just added to our portfolio, to kind of look at where we are with low Earth orbit and where we want to go with the Moon and Mars.

Kenna Pell

I didn’t know about the the space sustainability.

That’s cool. And Ryan first time on the podcast, and hopefully at the end of this you also say the same thing. Joel said that you are willing to come back anytime, because you’re going to be great. So as manager of the research Integration Office, what do you do? And can you tell our listeners how that connects to Space Station?

Ryan Landon

Absolutely. So I have the privilege of managing the ISS research Integration Office, and there the team manages essentially the full life cycle of an investigation, from concept all the way through to operations, guiding the researchers through their software and hardware testing, safety verifications, manifesting and the people who work in the Research Integration Office are the Primary intersection, I would say, between the users of the orbiting laboratory and the people, all the people in the ISS program who make it happen.

Kenna Pell

So talking in reflections of your time working International Space Station, I want to ask what were some of your first experiences working space station? And Ryan, why don’t we go to you first and you tell us how you got to NASA.

Ryan Landon

I had to grin when I was asked to do this one on the international aspect, because that’s really the word that really got me here. I was just graduated from college and saw an article, about the Mir space station. Didn’t know it existed. Read this whole thing. I thought it was absolutely amazing. We were doing something like that in space. And there was this little paragraph at the end that said, we’re building an international space station in Houston. We need people. So I applied and moved to Texas, not knowing a soul.

Kenna Pell

I love that. What was your first role here?

Ryan Landon

My first job was in Mission flight operations. I was a communications and tracking officer. I was also the only one in my group who wanted to work and live in Russia. I guess, I guess Joel dragged me into it, so I got to be in charge of all of the communication displays for the FGB launch.

Kenna Pell

Got it. Joel, I when I was listening to the earlier episode for the 20th anniversary, you’re talking international collaboration, I liked how you had mentioned, you know, we go back with international collaboration from Apollo-Soyuz. But then there was Mir, where we were visitors, right? And then we started working space station together. Can you tell us? Or just maybe looking back, you know, in your roles, various roles here at NASA, I guess, just walk us through your journey to where you are now and then, you know, maybe include some insights of, you know, your time in Russia.

Joel Montalbano

Okay, very good. So, you know, Ryan mentioned the Shuttle-Mir program. That’s, you know, where I started. And so I was a Russian interface officer during the Shuttle-Mir program. And throughout those missions, we learned how to fly long duration missions in space. And so that doesn’t mean we finished. We’re still learning today, you know, after 25 years of continuous crew presence and even more, with the space station as we, you know, since we started early before we had the permanent crew presence, we learned every day when we fly in space station. Then, you know, after I was able to do the Russian interface officer, I was selected as a flight director, and so I did the flight director job, which was pretty cool, again, one of the coolest jobs in the world.

Kenna Pell

Wait, I always ask, what was your call sign?

Joel Montalbano

My call sign was Flash. That was Flash Flight. And people ask, why Flash? And so when you look at some of the mission operations, kind of the how we base ourselves on what we do. There’s a sentence in there that says, Be ready at any time for something to happen. And so it says a little more than that, but I summarized it. And so I took that as, be ready in a flash, to be ready to act on orbit as a flight director and take the necessary actions to protect the crew and protect the vehicle. And so that’s why I picked Flash. And it was fun. I had a great time being a flight director. I was a flight director for about eight years. After that, I was asked by Mr. Suffredini to go ahead and see if I wanted to move to Russia for a year and be the Human Space Flight Director, Russia. So the guy in charge of all our operations in Russia and Kazakhstan. Four and a half years later, I finished that job, even though he said it was a year, but spent a little longer. I came back, and I was the deputy program manager in the International Space Station program for a number of years, and then became the ISS program manager after Kirk Sharman. And then after that, I was asked by Ken Bowersox to be his deputy up in Washington. So cool jobs, be a flight director. Being in Russia, one of the coolest things about being in Russia and leading our operations over there, I was able to go to every launch, every landing. You know, we were there at landing sometimes within five minutes of the capsule touching the ground. And you can smell the, you can smell space. It’s weird. It’s hard to explain, but you can the smell that the capsule has when it lands and and be there when our crew members get out is again, I’ve been pretty lucky.

Kenna Pell

Yeah. Ryan, over to you again, you know you’d mentioned your path to NASA, how you got here from Wyoming. And it thought it was so interesting, because it’s, you always hear that in astronaut stories, right? Like, you know, they get the call and they’re going to Houston, and it seems like something they would have never expected to move to Texas, or something along those lines. And can you tell us a little bit more about, where you left off and how you got to NASA, your first couple jobs, and where you’re at now,

Ryan Landon

Sure, sure! I try to copy Joel any chance I get to tell people how cool our jobs are every single day, we are so fortunate to work in a program and in an industry, really, it feels like you’re spoiled coming to work because you’re really connected to something bigger than, bigger than you. That was part of the draw to come here. I’ll be honest, when I first got here, I had mentioned nobody in my group wanted to go live and work in Russia. And I was I was all about that. I was super excited. I actually signed up, under Joel’s tutelage, to go and I had the opportunity to sit on console for the FGB [Functional Cargo Block, Russian Zarya Module] launch, since I’d built the displays to read their comm systems. And after that, I jumped on an airplane and flew to Moscow. And so I got to be in the Houston part of the Moscow control center for the first Shuttle flight to space station where we mated Node One and FGB, but there was this moment, and Commander Cabana called down something like, “Houston, we have a space station,” and you could hear the cheers throughout the entire TsUP. And listening to everyone hear that call down was pretty amazing. It was one of those kind of take your breath away moments that we have in this career.

But anyway, stayed in- I stayed in ops for about four or five years, and then saw some jobs that interested me in the program. And so I moved up to the program early 2000s I’ve worked for offices, I think, in the program, but I did work in Mission Integration, in the early expedition flights, where I got to define requirements for us to do every single expedition for every crew through assembly, I worked over in the MER [Mission Evaluation Room], which was a crazy time through the primary flights for assembly, like 2005 to 2012 when shuttle retired and getting to work every single shuttle flight putting each piece of the space station up, so many stories there. You guys could probably do 15 podcasts on all the little things that happened during assembly, and still, every single one of those pieces went together perfectly. It had never, ever been together on the ground. Just blows my mind every time I think about it.

Like Joel, I got a call from Suff, was a little different, I didn’t have to go to Russia again, but I did go work payloads about 12 ish years ago. I went to work payloads for just a couple years, and then back to Mission Operations, and here I am again, back in the Research Office. I like to think of my career as early on, I had fun when I was young sitting on console getting, you know, everyone can stay up all night then, getting to be in the engineering room when we were building it, but then getting to lead the office to do the research, which is the whole reason Space Station’s in the sky. It’s just, it’s a privilege.

Kenna Pell

I love it.

Joel Montalbano

And Ryan was in one of the critical times of Space Station. She was in the Payload Operations. You know when, when Mr. Sufferini was here, he made a change that said, Hey, we’re not going to have a bunch of offices and then a payloads or a research office. We’re going to put payloads and research in every office and really change the picture of the International Space Station Program. And Ryan was in there early enough, and helping us make that change and directing and forcing that, it wasn’t, it’s not an easy change of what we were asked to do and what Ryan and her team and others did was just unbelievable.

Ryan Landon

Thanks. That was… culture change is hard, and that’s really what Mike had asked us to do. I think one of my hardest meetings I was ever in was looking Mike in the eye and saying, it’s not working. We have to do something different. But then the whole team did, we really refocused the whole program on research, and the results we have today clearly show that that we were successful in that.

Kenna Pell

I love how you took us through, through assembly, to that critical moment with NASA astronaut Bob Cabana saying, “Houston, we have a space station.” Taking us through assembly, and then to the point where, you know, Julie had mentioned this in the earlier episode, about maximizing utilization as much as we could, and giving authority to all offices across the program to make sure that, you know they’re fulfilling that need since we built it. Okay, let’s maximize use of it.

Joel, back to you, in the growth of Space Station, were there any milestones that stood out to you from the international partnership standpoint?

Joel Montalbano

To me, when, when we put the major laboratories on orbit, the US Lab, the Columbus module, the Japanese laboratory, the Russian laboratory, you know, those were big milestones, right, that we’re able to rally around and it helps us complete what we’re really trying to do is maximize- use the research and exploration work that we’re doing on Space Station today for Artemis. All those things were huge contributors. So to me, every time we made a major contribution like that from an international partner was a pretty big deal to me.

Ryan Landon

I was reflecting while Joe was talking: I love having two people having this conversation, because every time I think of the international aspect, most of the times that I saw real serious collaboration was when something had broken, and watching the international teams having to come together across oceans in different countries, and really putting all of the data and all of our smarts on the table to figure out, how were we going to fix this so we could keep going? It really gave you a sense of “it was one team all the time”. It’s just one team.

Kenna Pell

Yeah. Furthermore, with maximizing use of space station after assembly and working with different international partners and different, you know, commercial partners, academia folks that want to get their, their science to Space Station, you know, your office, Ryan, you can kind of see what research that you’re already doing, what platforms we already have so that different, you know, international partners. Maybe there are researchers or principal investigators want to use these different sort of platforms that already exist on space station. So just kind of an explainer of, you know, maximizing all of the equipment and items we have up there.

I did, let’s talk about science. So moving into science, speaking of the segue to science, how is your office? Ryan enabled groundbreaking science and tech demos on station.

Ryan Landon

You know I talked about the role of my office, integrating all the investigations to get them ready for ops and flown to Space Station and operated. But the bigger piece of the puzzle is not just my office, but it’s the entire team of space station. It’s the people who work here. The teamwork that happens everyone in ISS has a piece, a part, of making this laboratory work.

Kenna Pell

And Joel, you talked about this a little bit, but how have leadership decisions supported research priorities and global collaboration on space station?

Joel Montalbano

You know, for the research, you know, NASA, the ISS program picks up launch costs. So your biggest cost to getting into space are your launch costs. We were picking that up. And what that allows us is, allows the science guys to base their funds, their time, on the actual on orbit product. They don’t have to worry about the cost of getting there. That burden is on the government. And so to me, that was the biggest thing we were able to do to help that team, and then to help them. We also were trying to look at, I’ll say, optimizing the requirements for everybody. So we had a standard set of requirements. And if you look at the standard set of requirements, that can be overwhelming. And so what Ryan and her team were able to do is tailor a lot of those requirements to specific payloads. So for example, one payload that maybe will go up there, it’s maybe it’s got a fluid like water or something like that. And the crew members can work on that, and there’s not a lot of requirements for that, but if you had a different experiment that had maybe formaldehyde as the substance, that’d be a different set of requirements. And Ryan and her team and others were able to work on that, tailor that, and just do the minimum set of requirements. So at NASA picking up the launch costs, Ryan and her team working to tailor the requirements for folks, we’re able to have the scientists focus on their experiment, get the results quicker and cheaper.

As far as international, what do we do for international? I think we, we NASA, have set the standard for international cooperation. There’s no bigger project that I’m aware of that has been as successful as we have been on the International Space Station, and we’ve got help from all over the government. It’s not just NASA, it’s all over the state department has helped us. The different administrations that have supported the International Space Station have helped us. Everybody has worked together to ensure we can work with our international partners. And then the same thing on their sides. You know, Roscosmos, the European Space Agency, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, all their teams have done the same thing to work together help us get to a common goal.

Ryan Landon

Can I go back to something Joel said earlier that I really like? You know, he talked about the work we did on the requirements and really individualizing what investigations have to follow, what requirements, part of that was the culture change we worked on, and getting people, the whole team really to realize that science can fail, and that’s part of the science. And so switching our mindset from being engineers and everything has to go together, work together perfectly, to we’re doing science, and sometimes it doesn’t work perfect. And as long as we’re keeping the crew and the vehicle safe, we’re there to experiment, and that was a huge shift in how we thought about how we thought about doing our work.

Kenna Pell

I’m glad you brought that up, because I was going to ask, and I thought that was an interesting topic that I don’t think we’ve talked about on the podcast. So those requirements, was there a point in time where you felt like there were a lot of platforms and things that could support or kind of standardize these requirements, or were there always, ever changing elements to them?

Ryan Landon

I would say, you know, that’s totally my reflection. But as you look back over all of the major NASA programs, as we go through history, each program learns from the previous and we adopt what they learned, and we add to it, right? Well, station’s the longest standing program there was. There were a lot of years so far to add to it and add to it. And we got to the point, after we talked about Suffredini changing it and wanting to focus on science, we had science customers coming to the program saying we can’t do this. It’s too hard, it’s too confusing, it’s too cumbersome. You have to change it if you want people to fly and so that’s really when we had to take a step back and go look at what were we doing. That was too much that we really didn’t need to do.

Joel Montalbano

Probably the biggest change is in past programs. NASA was responsible for mission success, and so we would work with these scientists to go down to the smallest detail to make sure what they did was as successful as possible. The challenge with that is that made the process longer. It took longer to get that payload ready. It took longer to fly. The change that was made was we put mission success now on the scientists so they could, we had the minimum set of requirements to keep it safe for the crew, safe for the vehicle, and then they can work on mission success. And what that allows them to do is allow them to go faster, right? So they can build a payload, they fly it, and it maybe doesn’t work right on the first time, but they can come home and so, and maybe in a three year period, they can fly two times, maybe three times, whereas in past programs, you may fly once in 10 years. And so we were able to increase the speed of the science increase the results, and that’s kind of where we are today. And hopefully that’s the standard for moving forward the future programs.

Kenna Pell

Where in this timeline, did we open International Space Station to commercial industry through cases or international…?

Ryan Landon

So the kind of the way the timeline went is Congress declared that the ISS was going to be an ISS National Lab, which is, when you step back and look at it, is really pretty cool. It’s the only national lab that is off the planet. Part of this decree was that the national lab would be independent from NASA science. And so Joel’s talking about how from earlier we were making sure NASA science was successful, NASA no longer owned the science that we were doing on ISS, so it really wasn’t ours to define what was success and what wasn’t success. And that was the big change. Most of this happened in the early 2010s was when we realized we really needed to make a shift. Yeah, so about 15 years ago.

Kenna Pell

Okay, and I love how we kind of talked through, you know, stages of assembly utilization, and then what we had been kind of coining the decade or results, where all of these results are kind of compounding and building off of each other. Ryan, back to you. On the topic of science, can you share some of your favorite examples of impactful experiments and research done on station?

Ryan Landon

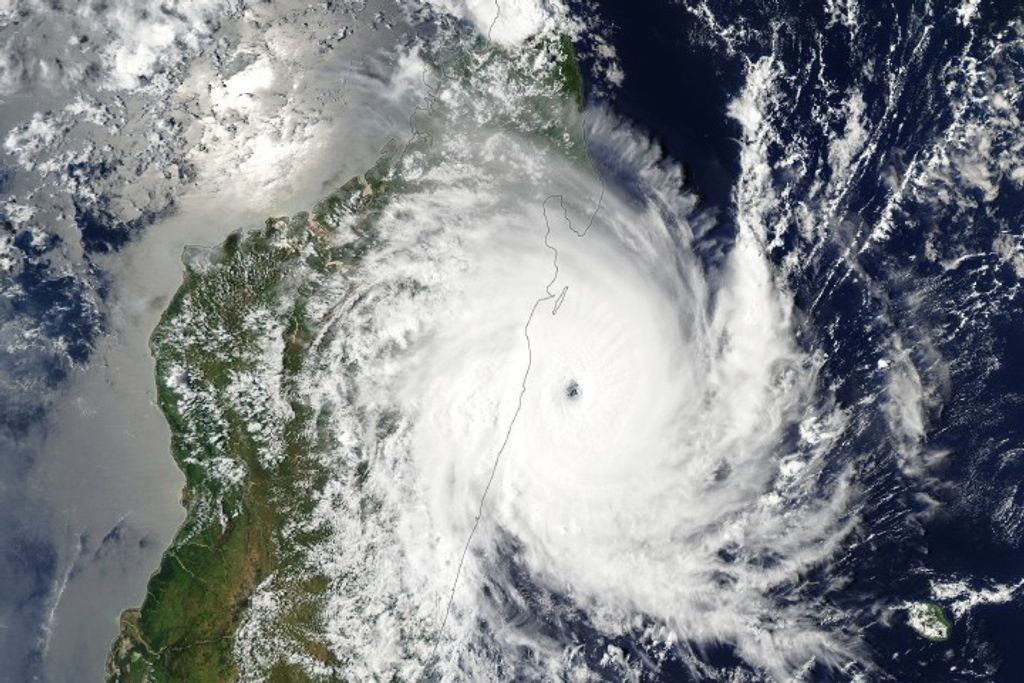

Sure thing, there’s so many now I tell everyone in my team to pick your favorite. So if someone runs into you in the elevator, you can tell them all about it as you’re going up your sixth flight of stairs, or whatever. Some of my favorite ones are really starting to hit the markets now and impact life on Earth. So for example, we are growing protein crystals in micro gravity that lead to larger, more organized structures that can help in developing new medicines for cancer, muscular dystrophy, other diseases that we’re working on. Last year and the year before, we printed actual human tissues, we printed a knee meniscus, which could be helpful for me later, also some heart cells beating headed up to orbit and back bio-printed on the ISS. The aim in that when you fast forward in your mind is being able to print a specific organ for a specific person on earth with their own cells that you flew to space. Photos taken by the astronauts have aided in response to natural disasters, hurricanes, emergency response, targeted views from space. Scientists have created and studied the fifth matter for the first time on the International Space Station. This is allowing researchers to learn more about quantum science and advanced technologies, not only on Earth, but also in space. We’ve also discovered cool flames in space. This is a phenomenon that’s extremely difficult to study on Earth, and it’s opened up new frontiers in combustion science and engine design.

Kenna Pell

Joel, taking from Ryan’s book, what is your elevator pitch? Your favorite experiment, most impactful that when you’re like you said, going up the six flights of stairs, but on an elevator, what are you talking about?

Joel Montalbano

I think there’s one experiment we do with the eyes, a retina experiment that we’re just, we’re just, it’s in the early phases, but it’s, it has the possibility to help restore sight in people that can‘t see today. And to me, how cool could it be? Would it be if, if you’re able to tell people that the International Space Station is used to help people that are blind today see tomorrow? I mean, that would be the, to me, that’s that was so good, right? And it would be, it’d be awesome.

Kenna Pell

Yeah, okay. Speaking about your one liners are really good. You almost said this exactly the same way of the way that, you know, we have it written on the website I always love, and I always go back to, is that “the International Space Station program’s greatest achievement is as much a human achievement as it is a technological one.” I want to talk a little bit more about the 25 years of international partnership. Joel, over to you. Can you tell us about the partnerships that we foster with our international partners?

Joel Montalbano

Sure, one of the benefits of the International Space Station is when you look across all the countries that participate in what we do, no single space agency has the funds or the resources to do what we do on the International Space Station. So what we’re able to do is take these five participating space agencies, put them together, take the best from each agency, funds from each agency and put together an international cooperative program across the globe. To me, that’s again, there’s not an example that I’m aware of where we’ve done this for this long amount of time and have been as successful. We’ve been pulling this together. We’ve had our ups and downs. You’ll have challenges. You know, each space agency also has their national goals and needs, and so we’ve been able to work together to manage that. So every agency continues to keep their national goals, but they also have international work that we do across the different partners and stuff that we do every day on space station that’s helping us, not only in low Earth orbit, that’s going to help us for exploration and help the Artemis program.

Kenna Pell

Do you have any stories about specific teamwork, or times that different perspectives and working with the different partner agencies came together to maybe solve a bigger problem.

Joel Montalbano

One of the biggest examples, I can tell you is, you know, when we had the Columbia accident, Roscosmos stepped up and we were flying on the Soyuz vehicles to keep a presence on the International Space Station. That is just one of probably 100 examples of that we’ve done across the partnerships, where when one partnership stumbles, another partner picks it up every time. It’s, it’s like clockwork. It’s, it’s impressive the watch. It’s, it’s humbling to watch.

Ryan Landon

It is, it is, I always think back to some of the items we worked in the MER, right? One time we had a Russian power box go down, and it was all the US side supporting the Russian segment until we could figure out what was going on with that box and get it up and fixed. At the same time, another time, all of our computers went down, all of our command and control MDMs went down. And so we had to rely on the Russians and the shuttle that was talked at the time to literally keep us in orbit until we could figure out how to fix it. As a partnership.

Kenna Pell

Joel, you’d mentioned that, you know, the different agencies, maybe bringing different viewpoints, maybe different ways that they go about doing business, and things like that. I was just thinking back to those early, you know, the beginning of the International Space Station, I have a funny question, but where did you guys decide things like, what time we were going to go with, you know, what were those initial meetings like? And then could you go and kind of explain a very high level overview of U.S. provides this, Roscosmos provides that. JAXA here, CSA with this.

Joel Montalbano

Sure. Let’s see the time.

Kenna Pell

Sorry, my silly question.

Ryan Landon

It’s all good history.

Joel Montalbano

We’ll start with the time. Obviously, as everybody knows, we use Greenwich Meridian time.

Kenna Pell

Does everyone know that?

Joel Montalbano

Okay? For everyone out there, we use Greenwich Meridian time. And why is that? Because if, if you can’t be in Houston, if you say 10 o’clock is at 10 o’clock Houston, is it 10 o’clock Munich? Is it 10 o’clock in Moscow, Tokyo, Montreal, and so we had to come up with a standard time. And Greenwich Meridian time is makes the most sense why we picked where we’re at. So when you look at the crew awake and sleep schedule, the crew is awake. The first part of their day is the Moscow work day, and then the second part of the day is the main Houston work day. And so the times that we picked may made sense, and that’s kind of how we went with that. So you know, generally, the crews waking up around midnight Houston time, that first part of days during the Moscow prime work day, where they have the A team on and working. And then as you go, they kind of go into the late afternoon and evening shift, and then Houston picks up, and it’s our prime team working the Houston orbit there. And then in the afternoon, Houston time or so, the crew goes to sleep. And again, the way it works, if you’re not aware, is that we do have a standard sleep and wake schedule. Not- we don’t have someone up all the time like we did on some of the older shuttle missions where we had two crews. So we don’t do that on space station.

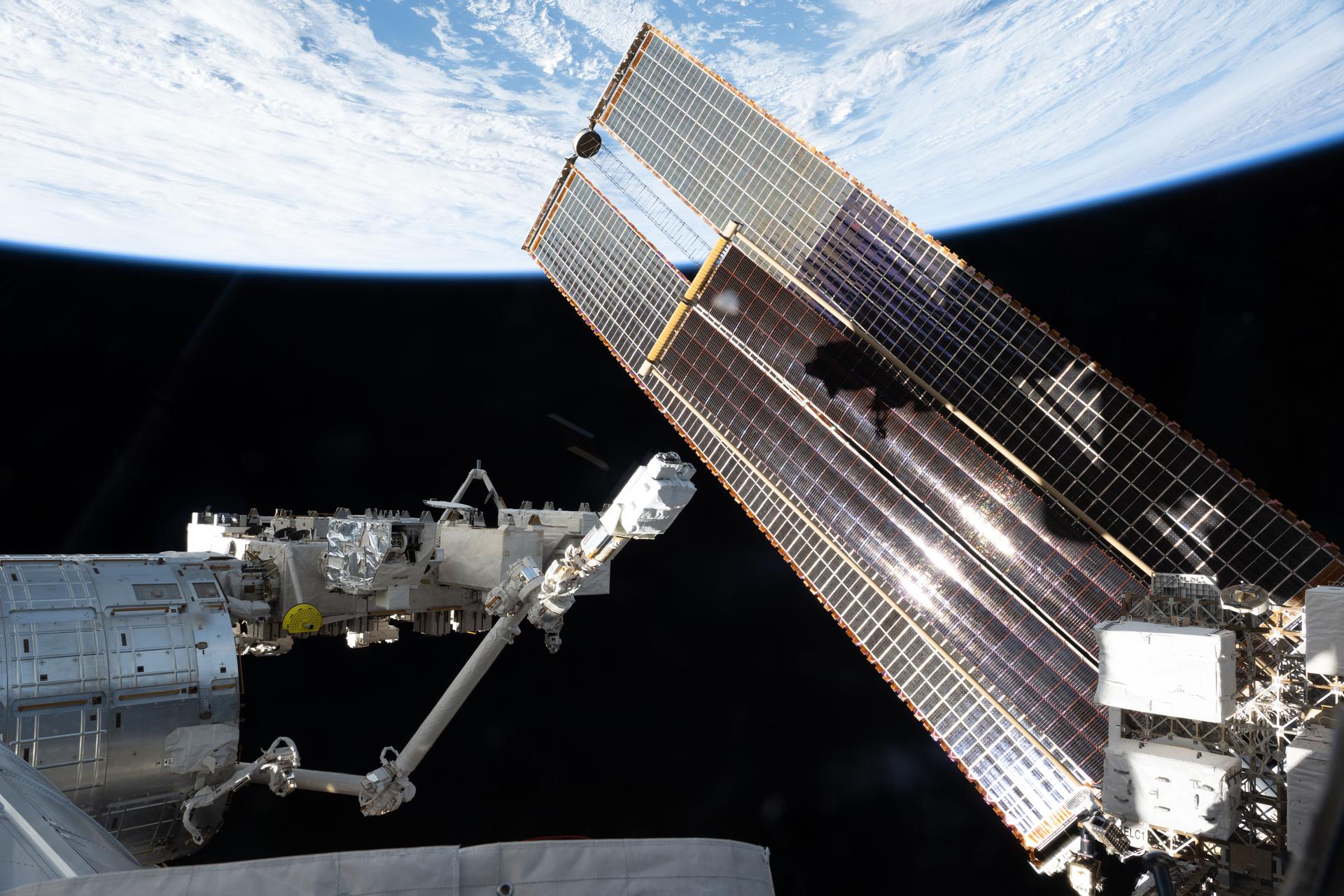

And then let’s see your main contributions. So when you look at it, the US main contribution is power, right? You look at the solar arrays that we have in and even the recent upgrades we’ve been doing with the roll out solar arrays, we’re the masters of power. We provide the majority of the power the International Space Station, Roscosmos, they have. They supply the propellant, the majority of the propellant for and for attitude control. Now we’re starting to use some of our commercial providers to add that capability, but Russia has been prime for that. And these are just some examples.

There’s many- the Canadians they provide the robotic arm. Look at how much work we’ve done during assembly and after assembly, the robotic arm, I think, has been busier after assembly as much or more than it was during assembly. The Japanese the laboratory that they have, the airlock that they have, they have a small science airlock that we use. The European Columbus module, the different science we can do, and that module, everybody contributes a significant apart, and you put it all together, and it just makes the five space agencies so much more powerful when we work together.

Kenna Pell

I love it. So we’re on the heels of humanity’s return to the moon for the first time in over 50 years with Artemis II. And I want to talk about how space station has paved the way for NASA’s journey to the moon and then eventually to Mars. How about Ryan? Can you explain to our listeners how station served as a test bed for those technologies and different systems that we’re testing on. You know, even this upcoming test flight of Artemis II?

Ryan Landon

Absolutely, ISS is a crucial proving ground for testing capabilities for deep space exploration, learning what we need to learn about humans so we can travel further. Further into space. Some specific examples that we’ve been successful with on Space Station really revolve around life support system. We have tested multiple different, I’ll say, generations of life support systems on space station. We’ve gotten to the point where we can reclaim 98% of our water on ISS, which was a huge milestone for exploration. Food, we’ve been grown over 50 species of plants in space on space station. I didn’t actually know that until I was prepping for this. I thought that was a pretty impressive number, everything from tomatoes to bok choy to lettuce, chili peppers. Testing out different facilities and food systems for what we could use for exploration, different ways of growing crops helps us for exploration, but also helps us down back on the earth for agriculture industry.

We’ve already talked about 3D printing. We were talking about the bio side, but also on the physical side. Astronauts have used recycled plastics or stainless steel to print tools or small metal parts or things that they might need that will help in explore. Education, doing in in situ maintenance. For example, we don’t have the tool that they need on the moon, so they need to go print it. Also looking at different construction materials that use regolith or moon rocks or materials from Mars that they can use while they’re there, that we don’t have to launch.

Kenna Pell

How about the human health and performance side

Ryan Landon

Definitely, if we plan to send humans into Earth, we need to know how to keep them safe and bring them back home. And we always hear about exercise. The crew has a very rigorous exercise schedule. They can ride a bike, they can run, they can walk, they can even do weight lifting type exercise. This is protect their health as they venture further into space, so they’re also healthy when they return back to the Earth’s gravity. We monitor their health, all different all different aspects of it. Their eyes. We know the astronaut eyes change in orbit, and so we monitor that to make sure that we understand what’s going to happen over the long term. We look at joint health, cardiovascular health, sensory motor function. We see changes a little bit when you’re in zero gravity, and understanding how human bodies adapt to space is important for longer durations.

Kenna Pell

Absolutely, and Joel over to you. Can you tell us about how the role of international partnerships formed through ISS helped shape the Artemis program?

Joel Montalbano

Sure, you know the space station and even you talked it earlier, even going back to Apollo-Soyuz, those were the building blocks of what we’re going to do moving forward. I mean, just look at the Orion spacecraft. You have an Orion spacecraft with a European provided propulsion system. And so that’s just one example of where we’re working together. There’s examples where the Japanese are going to contribute something to the Gateway program. You have the Canadian, Canadian robotic arm, you know, looking forward. So everybody is looking at opportunities and and we’re using the lessons learned that we gained on the International Space Station to make us a stronger, more robust Artemis program.

Kenna Pell

Wonderful. 50 years from now, what do you hope humanity takes away or remembers about the International Space Station?

Joel Montalbano

To me, I hope when people look back and 50 years from now, there ought to be regular missions to space, at least low Earth orbit. Hopefully it’s like airplane travel today. And so when people look back and they say, you know, how did this get started? My hope is that the International Space Station was a small part of that to make that travel to space as routine as airplanes are today.

Ryan Landon

You know, 50 years from now, I almost hope they think of Space Station as the Wild West. We did a lot of things that we weren’t really sure if it was going to work or not, but we had the courage. We tried it out, worked or it didn’t. We learned and we moved on. And I hope, as we look back in space history and NASA history. There are, there’s a giant beacon of ISS that was a major stepping stone to what comes in the future.

Kenna Pell

That was wonderful. And did you think of coming to Houston to support this concept of being the wild west as well, even then?

Ryan Landon

Yeah, a little bit, you know, when I, when I first thought of coming here, I knew it was just starting, and the thought of being in the middle of something that was just beginning was was really intriguing for me.

Kenna Pell

Yeah. Joel Ryan, thank you so much for joining us.

Joel Montalbano

Thank you.

Ryan Landon

Thank you

Kenna Pell

Thanks for sticking around. I hope you learned something new today.

This was the fifth episode celebrating 25 years of continuous human habitation on the International Space Station. You can check out the latest from around the agency at nasa.gov, and you can learn more about the International Space Station at nasa.gov/station.

Our full collection of episodes and all of the other wonderful NASA Podcasts can be found at nasa.gov/podcasts.

On social media. We are on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, X, and Instagram. If you have any questions for us or suggestions for future episodes, email us at nasa-houstonpodcast@mail.nasa.gov.

This interview was recorded on December 15, 2025.

Our producer is Dane Turner. Audio engineers are Will Flato and Daniel Tohill, and our social media is managed by Kelsey Howren. Houston We Have a Podcast was created and is supervised by Gary Jordan. Special thanks to Kara Slaughter and Mary Pfister for helping us plan and set up these interviews. And of course, thanks again to Joel Montalbano and Ryan Landon for taking the time to come on the show.

Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on, and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.

3… 2… 1… This is an official NASA podcast.