NASA Rocket to Conduct ‘CT Scan’ of Auroral Electricity

A NASA rocket mission will soon launch from Alaska to reveal the electrical circuitry underlying the aurora. The rocket will use a technique similar to a CT scan to reconstruct the electrical currents flowing from the northern lights. The Geophysical Non-Equilibrium Ionospheric System Science, or GNEISS (pronounced “nice”), mission will launch from the Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, Alaska, as early as Feb. 7.

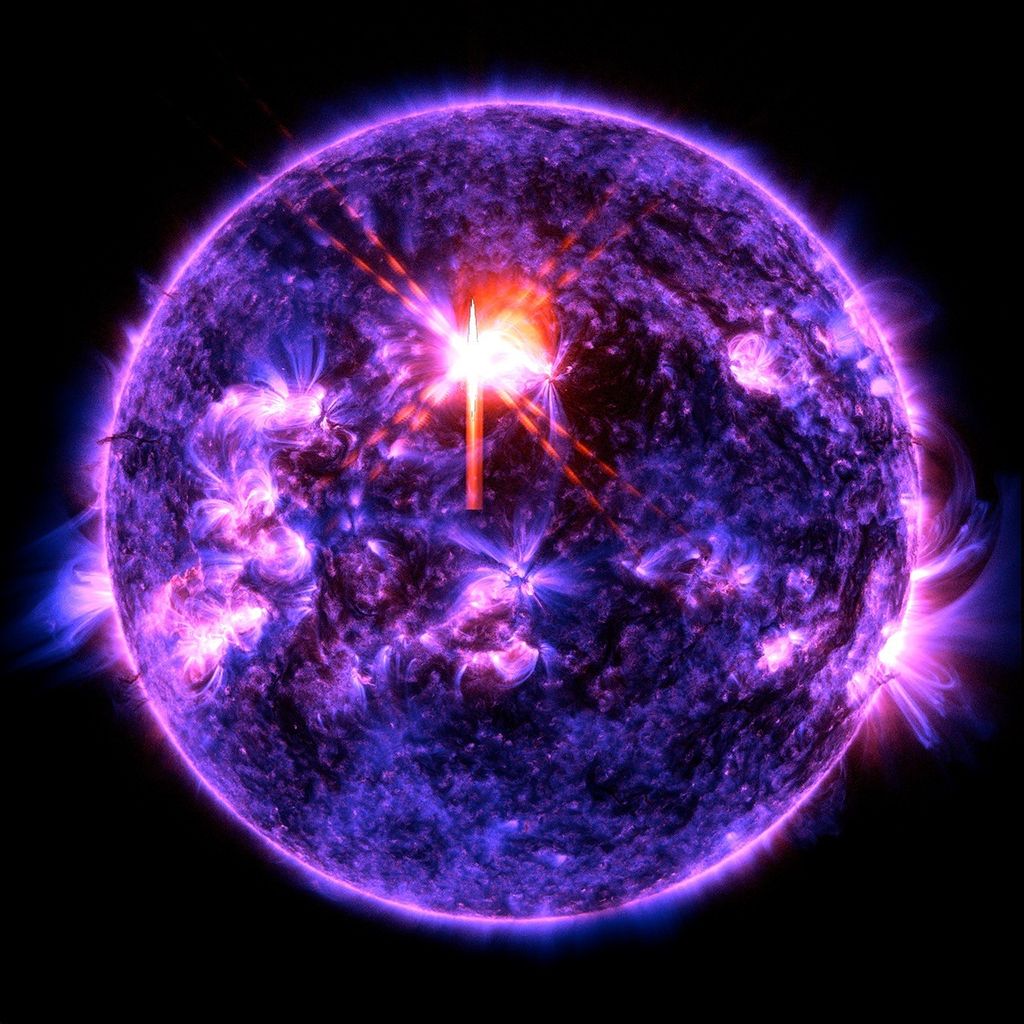

When an aurora lights up the sky, it’s because electrons are flowing from space into Earth’s atmosphere. You can think of these electron beams like the electricity flowing through a cord to illuminate a lightbulb. The electricity doesn’t stop where the light appears. Electricity travels in loops; the lightbulb is just a pit stop on a roundtrip journey known as a circuit. If the light is on, electrons aren’t just flowing in — they’re also flowing back out through the power cord from whence they came.

For auroras, the incoming electrons flow along beams that resemble a power cord, but the current flowing back from the aurora is not nearly as organized. After setting the aurora alight, the auroral electrons scatter in unpredictable directions. Collisions, diverging winds and pressure gradients, and transient electric and magnetic fields all shape their paths. They ultimately find their way back to complete the auroral “circuit,” but only after meandering through the ever-shifting chaos of our atmosphere.

To understand how the aurora works, we need a clear picture of how the auroral current closes, including the winding paths electrons take after sparking the aurora. Yet observing that returning current is no simple feat. It means somehow scanning all the possible paths the electricity could take.

“We’re not just interested in where the rocket flies,” said Kristina Lynch, principal investigator for GNEISS and a professor at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. “We want to know how the current spreads downward through the atmosphere.”

Lynch designed GNEISS to do exactly that. With two rockets and a network of ground receivers, GNEISS will create a three-dimensional view of the electrical environment of an aurora.

“It’s essentially like doing a CT scan of the plasma beneath the aurora,” Lynch said.

The GNEISS mission launches its two rockets at the same time, flying side by side through the same aurora along different “slices.” Once inside, each rocket will eject four subpayloads. These subpayloads measure distinct locations inside the aurora.

As the rockets fly overhead, they send radio signals through the surrounding plasma to receivers on the ground. The plasma alters those radio waves en route, in the same way different body tissues alter the beams from a CT scan. The GNEISS team uses these radio signals infer plasma density, which reveals where electricity can flow. It’s a large-scale auroral CT scan.

Figuring out how auroral currents work isn’t only about filling in a missing piece of physics. Those currents shape how energy from space spreads through Earth’s upper atmosphere. Where the current fans out, the atmosphere heats up. Winds stir, and satellites plow through unexpectedly turbulent air.

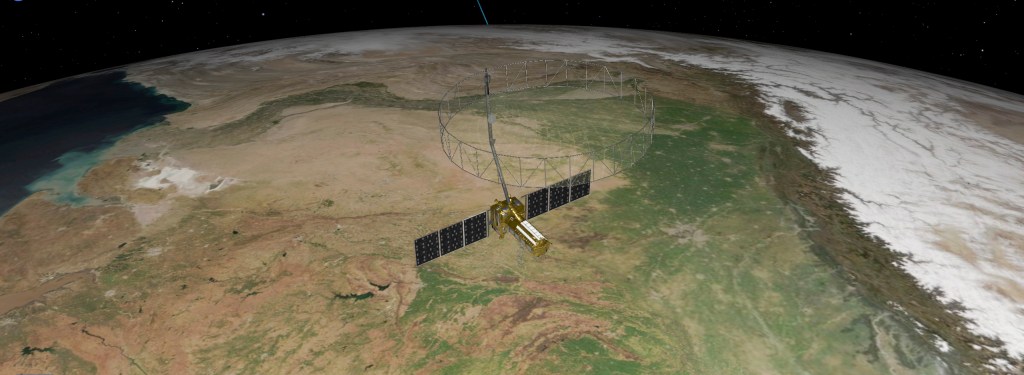

Scientists have long studied the atmosphere where auroras form using ground-based observations. NASA’s EZIE satellite mission, launched in March 2025, determines auroral electrical currents from above. Combining those measurements with rocketry, GNEISS offers a rare chance to actually look inside the system.

“If we can put the in situ measurements together with the ground-based imagery, then we can learn to read the aurora,” Lynch said.

The GNEISS mission won’t be flying alone. During the same launch window, NASA also plans to launch the Black and Diffuse Aurora Science Surveyor. This sounding rocket mission focuses on unusual blank spots inside auroras known as black auroras. Scientists suspect they are where auroral currents suddenly reverse direction. It will be the mission’s second attempt at flight, following a 2025 attempt when science and weather conditions were unfavorable for launch.

Auroras emerge where space meets sky. Electric currents, particle flows, and collisions create these natural wonders, and sounding rockets let us fly directly through them to place instruments exactly where the action is. With short, targeted flights and carefully timed launches, missions like GNEISS help turn brief flashes of light into lasting scientific insight.

By Miles Hatfield

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.