Contents

- Acoustics

- Anthropometrics and Crew Physical Characteristics

- Artemis Lighting

- Automated and Robotic Systems

- Cabin Architecture

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

- Design for Maintainability

- Electrical Shock

- Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS)

- Extraterrestrial Surface Transport Vehicles (Rovers)

- Habitable Atmosphere

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Test Subject Sample Sizes

- Lighting Design

- Lunar Dust

- Microbiology in Space Overview

- Occupant Protection

- Radiation Protection

- Spacesuits

- Suited Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

- Touch Temperature

- Usability, Workload, and Error

- Vehicle Hatches

- Waste Management

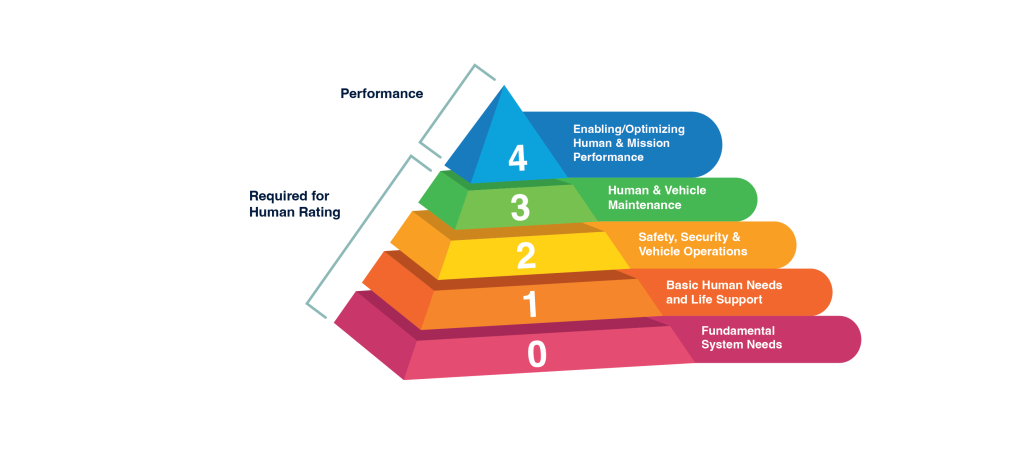

Spaceflight vehicles designed for human habitability must follow design considerations that accommodate the daily functions of the astronauts living onboard, including dining, sleep, hygiene and waste management, and other activities to ensure an efficient and healthy environment.

Acoustics

The NASA-STD-3001 Volume 2 acoustic standards ensure an acceptable acoustic environment to preclude noise-related hearing loss, preclude interference with communications, and support human performance. The standards are organized by mission phase due to the unique differences in noise levels and purposes of the standards. The launch, entry, and landing phases generate a great amount of noise caused by the combustion process in the rocket engines, engine jet-plume mixing, unsteady aerodynamic boundary-layer pressures, and fluctuating shockwaves. These phases also generate significant levels of infrasonic and ultrasonic acoustic energy. This short-term noise exposure normally does not exceed 5 minutes of continuous duration. The main focus of controlling noise during this phase of flight is on protection of crew hearing and preservation of critical communications capability.

During on-orbit, lunar, or extraterrestrial planetary operations phases when engines are inactive, the focus shifts from protecting crew hearing to ensuring adequate communications, alarm audibility, crew productivity, and habitability. Therefore, the maximum allowable sound levels are lower than those required for launch and entry.

Anthropometrics and Crew Physical Characteristics

The design of human-inhabited spacecrafts, spacesuits, and equipment must

accommodate for the physical size, shape, reach, range of motion, and strength of the crew population. Additionally, there must be considerations taken for the external factors that influence crewmember anthropometry, biomechanics, and strength including: the gravity environment, clothing, pressurization, and deconditioning during missions. To determine which measurements and data sets are applicable to the design of a system, it is necessary to understand the tasks that are being performed, the equipment that will be used, and who will be performing the tasks.

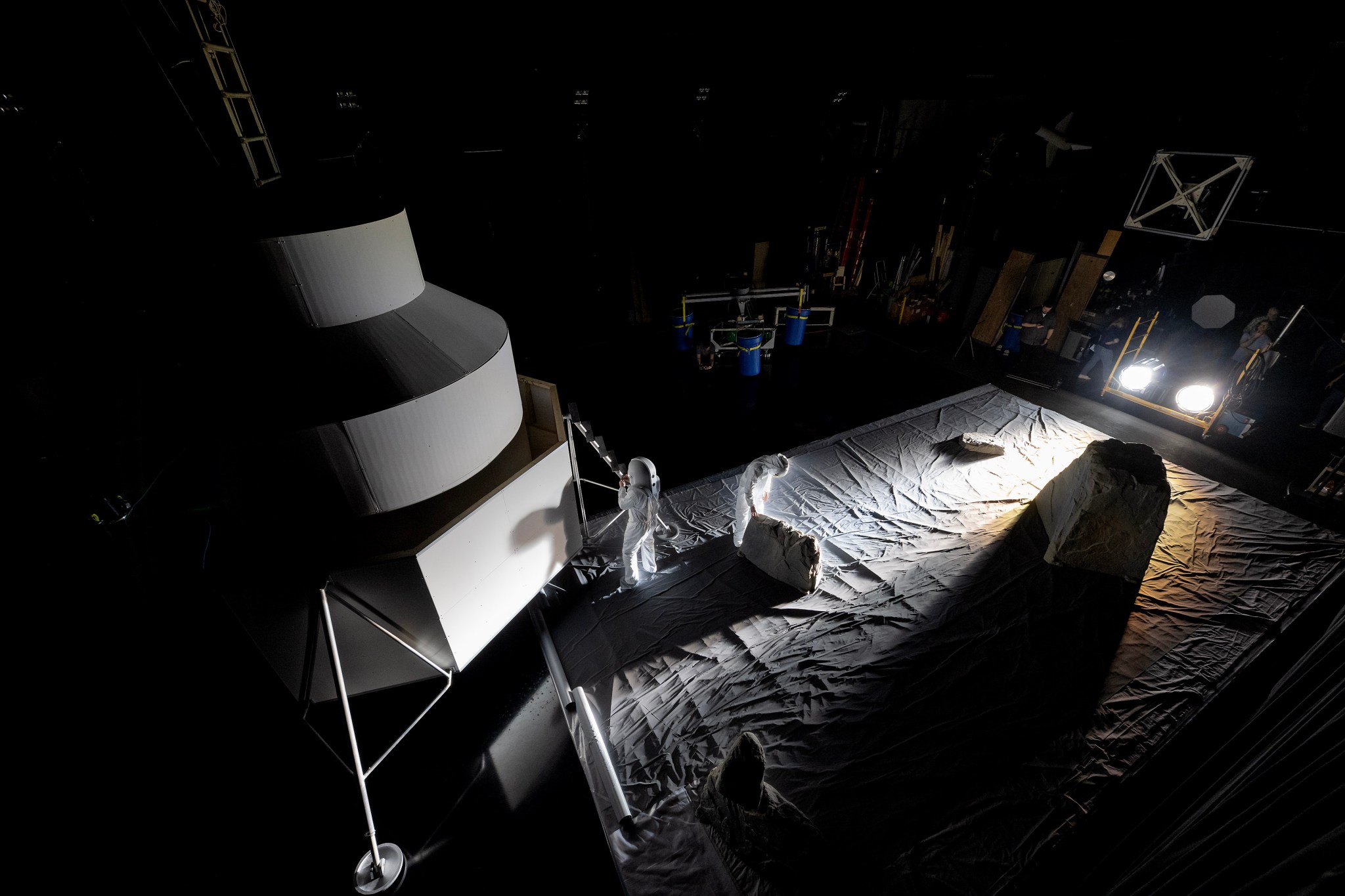

Artemis Lighting

NASA crewed spaceflight programs have had years of experience with the Space Shuttle and International Space Station (ISS) programs in performing exterior vehicle proximity activities such as crewed Extravehicular Activities (EVAs), robotics, docking, and inspections. These experiences have been operated in full sunlight every 45 minutes during each orbit in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). The lunar surface, especially at the South Pole, will have poor lighting conditions due to the day-night cycle lasting one Earth month (see photos below for comparison to Apollo conditions) and the extremely low angle of the sun relative to the South Pole surface. Exploration of exterior lighting systems need to plan for both perpetual darkness and perpetual harsh sunlight. This Artemis Lighting Considerations Overview Technical Brief is intended to provide guidance on development of an integrated lighting architecture plan that accommodates human and machine vision related EVA tasks. The lighting engineering process may involve trade-offs in meeting these needs within power constraints and physical restrictions on light sources and operator placement. Treatment of the solution as an integrated design project will provide or the development of all end-item components (suits, lunar terrain vehicle (LTV), Human Lander System (HLS), and Surface) needed to provide a productive lighting system that supports crew safety and performance of mission objectives.

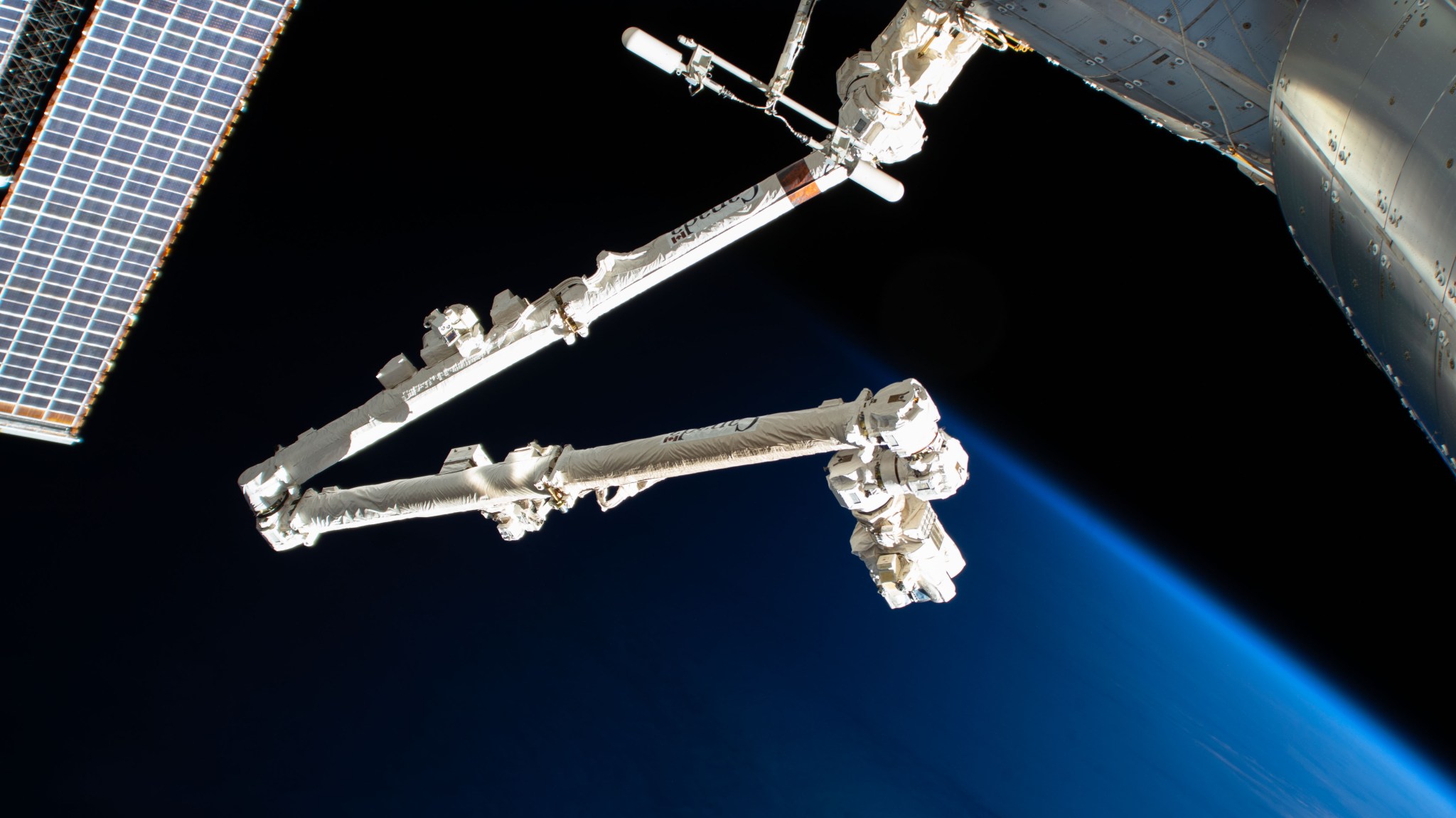

Automated and Robotic Systems

As missions, spacecrafts, and operations become progressively more complex, there is an increased reliance on automated systems and a need for diligence in enabling crewmembers to manage automated systems and subsystems. The human operator needs to maintain situation awareness to work effectively with automation, calibrate trust in the system, and avoid errors. Automation functions need to be designed around human roles for specific tasks, with the human operator having ultimate authority.

Crewmembers should have the capability to override and/or shut down the automated systems as long as the transition to manual control is feasible and won’t cause a catastrophic event. The allocation of responsibilities between humans and automation should seek to optimize overall integrated team performance.

Cabin Architecture

A cabin space intended for human use must keep the occupant(s) alive, support all the physical systems and cargo that a mission requires, and accommodate the activities the crew must perform. These necessities must be balanced against volume and mass limits imposed by the capabilities of the vehicle itself. Technical requirements in NASA-STD3001 Volume 2 aim to ensure the crew cabin contains all necessary features to maximize crew efficiency, human performance, and mission success.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

On Earth, physiological Carbon Dioxide (CO2) levels are managed by our lungs and environment. Our lungs collect vital oxygen (O2) through inhalation, circulate O2 throughout our body and to vital organs via the bloodstream, and then upon exhale, release CO2 into the environment. When our respiratory system does not function nominally, either from physical or environmental limits, CO2 can build-up in our bodies (hypercapnia) and cause symptoms such as headache, dyspnea, fatigue, and in extreme cases, death. Our environment naturally eliminates CO2 through photosynthesis of plants and trees, weathering, and other experimental CO2 removal processes. Humans in space face hostile, enclosed environments (including vehicles and suits) that do not have the benefit of natural CO2 removal, relying on CO2 removal equipment (e.g., the Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly (CDRA), lithium hydroxide, and amine systems) to help regulate CO2 levels in the environment and help decrease risk of negative consequences of elevated CO2 exposure.

Design for Maintainability

Perseverance, nicknamed Percy, is a car-sized Mars rover designed to explore the crater Jezero on Mars as part of NASA’s Mars 2020 mission. It was manufactured by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and launched on 30 July 2020, at 11:50 UTC. Confirmation that the rover successfully landed on Mars was received on 18 February 2021, at 20:55 UTC. As of 31 August 2021, Perseverance has been active on Mars for 189 sols (194 Earth days) since its landing. Following the rover’s arrival, NASA named the landing site Octavia E. Butler Landing.

Electrical Shock

For spaceflight applications, it is important to protect humans from unintended electrical current flow. These technical requirements define the physiological limits for current flow for the following situations:

- Nominal – Under allsituations

- Catastrophic – Hazard threshold for all conditions

- Catastrophic – Hazard threshold specifically for Startle Reaction

- Leakage Current – Designed for Human Contact.

Current thresholds were chosen (vs. voltage thresholds) because body impedance varies depending on conditions such as wet/dry, AC/DC, voltage level, and large/small contact area; however, current thresholds and physiological effects do not change. By addressing electrical thresholds, engineering teams can provide the appropriate hazard controls, usually through additional isolation (beyond the body’s impedance), current limiters, and/or modifying the voltage levels. “Catastrophic hazard” language is used to relate the physiological level that shall not be exceeded without additional controls.

Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS)

Humans living and working in space contend with a hostile/closed environment that must be monitored and controlled to keep the crewmembers safe and able to perform mission objectives. NASA-STD-3001 provides technical requirements that address the key aspects of the human physiological system that must be accounted for by programs employing human-rated systems. Compliance with requirements may be ensured with the tailored implementation of an Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS). The ECLSS provides clean air and water to crew in a manned spacecraft through artificial means. The ECLSS manages air and water quality, waste, atmospheric parameters, and emergency response systems.

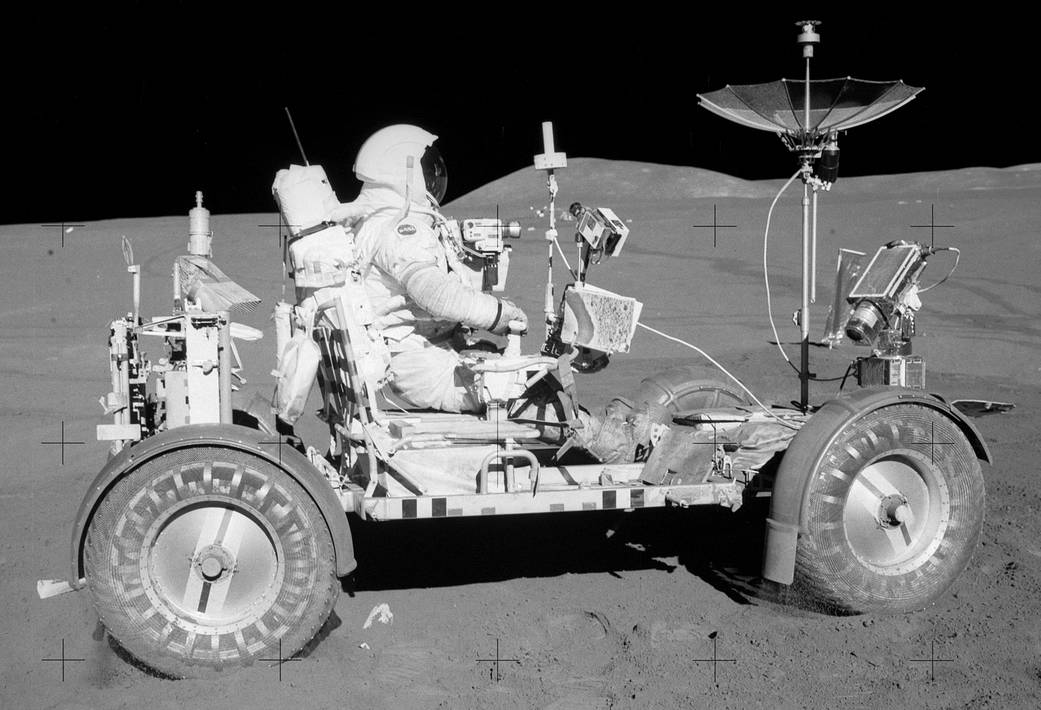

Extraterrestrial Surface Transport Vehicles (Rovers)

During any mission to an extraterrestrial surface, the presence of a transport vehicle (rover) will allow crewmembers to travel farther from their lander or base, carry more equipment, and perform medical evacuations. The rover presents its own set of risks and challenges, which must be overcome in accordance with technical requirements listed in NASA-STD-3001. Lessons learned from the Apollo program can be applied to ongoing design and implementation of lunar and planetary rovers.

Habitable Atmosphere

Space is characterized by hostile conditions including variable pressure,

changing temperature and humidity, and the lack of a survivable atmosphere. Spaceflight vehicle designers must develop life support systems that provide a safe and comfortable living environment, facilitate safe extravehicular activities, adapt to changing environments (including vehicles, rovers, and suits), and maintain the integrity of the space vehicle. In addition to vehicle design, the crew must be protected from conditions induced by atmospheric changes including inadequate oxygen supply (hypoxia or hyperoxia) and pressure changes that can cause pressure-related illnesses or barotrauma.

Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Test Subject Sample Sizes

Human performance varies based on a user’s unique experiences. Test subjects must be representative of the full range of potential crewmembers in both physical and cognitive aspects. Sample sizes for integrated Human-in- the-Loop (HITL) testing should look to incorporate enough test subjects to provide confidence in the statistic while covering the range of critical anthropometric dimensions needed for the tasks. NASA strongly recommends HITL tests verifying human performance parameters utilize 10 test subjects when the metric is sensitive to a user’s unique experience (usability, workload, error, etc.). NASA requires that metrics that are less affected by a user’s unique experience (such as legibility and glare) or utilize an even more homogeneous population (certified test pilots for handling qualities) utilize a minimum of 5 test subjects. Verification sample sizes consider end user population, statistical parameters, published data on the likelihood of finding errors, lessons learned, and past experience conducting HITL testing for spaceflight, and expert judgment with NASA community buy-in. There are no requirements on sample size for developmental tests and they can typically use fewer subjects. However, more mature systems should use a larger sample size during testing.

Lighting Design

Spacecraft lighting systems—inside and outside the vehicle—have a large number of contributing variables and factors to consider. Careful planning and consideration should be given to the development and performance verification of light sources, and for the system architecture integration and control of the lighting system. Improperly integrated lighting systems impact task and behavioral performance of the crew and can impact the performance of automated systems that rely on cameras.

Lunar Dust

Lunar dust exposure during the Apollo missions has provided insight and many years of research of an extraterrestrial environment that has not been visited by humans since 1972. Due to the unique properties of lunar dust (and other celestial bodies), there is a possibility that exposure could lead to serious health effects (e.g., respiratory, cardiopulmonary, ocular, or dermal harm) to the crew or impact crew performance during celestial body missions. Limits have been established based largely on detailed peer-reviewed studies completed by the Lunar Airborne Dust Toxicity Advisory Group (LADTAG). Research on lunar dust is ongoing, and emergent considerations (e.g., the presence of toxic volatiles in permanently shadowed regions, allergenic potential of dust) will be appropriately addressed as the risk is more clearly understood. The role of dust mitigation and monitoring is also highlighted here, as these contribute to the ability to characterize crew exposures and minimize risk.

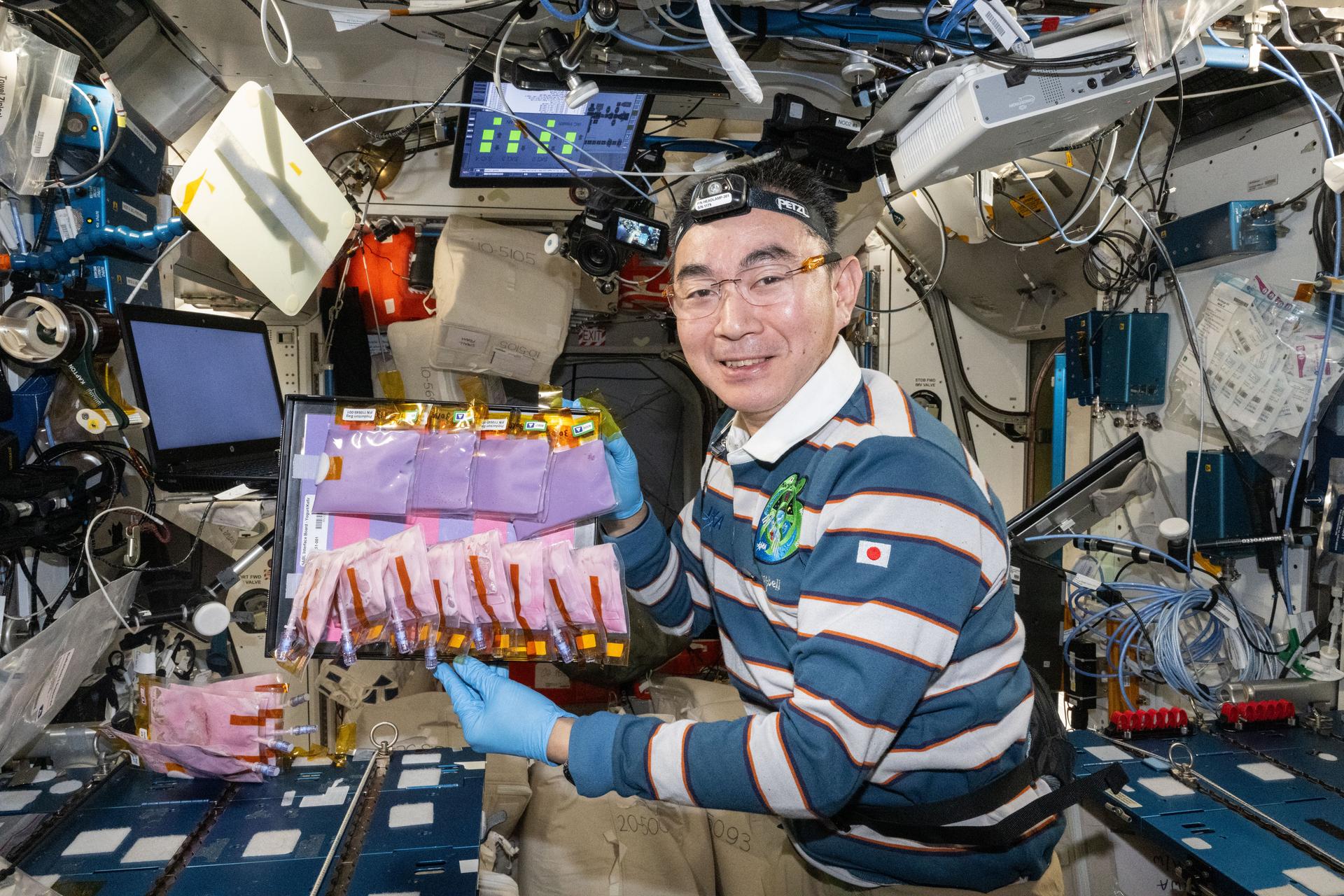

Microbiology in Space Overview

Microbial contamination in spacecraft environments poses risks to both crew health and onboard systems. Through the preflight Health Stabilization Program (HSP) and inflight cleanliness procedures aboard the ISS, there has not been a case of infections disease during flight. Implementing effective microbial control practices are crucial for long-term human operation in space. Specific measures are recommended for preventing crew and life-support system contamination, by adhering to human exposure limits and technical requirements, as well as developing deployable microbial control and disinfection strategies.

Occupant Protection

Vehicle designers must consider the various mechanisms of a vehicle’s system during dynamic phases of flight to protect the occupants, notably acceleration and vibration affects on humans. Acceleration limits are set in the x, y, and z axes for all mission phases to protect the crew from injury and other acceleration-related conditions. These limits are divided into two-time regimes:

- sustained (>0.5 seconds), and

- transient (≤0.5 seconds)

They are further divided according to:

- whether the acceleration is translational or rotational

- the phase of flight, and

- whether the crew is standing or sitting Excessive whole-body vibration can lead to fatigue, discomfort, vision degradation, and risk resulting from hand vibration reducing fine motor control.

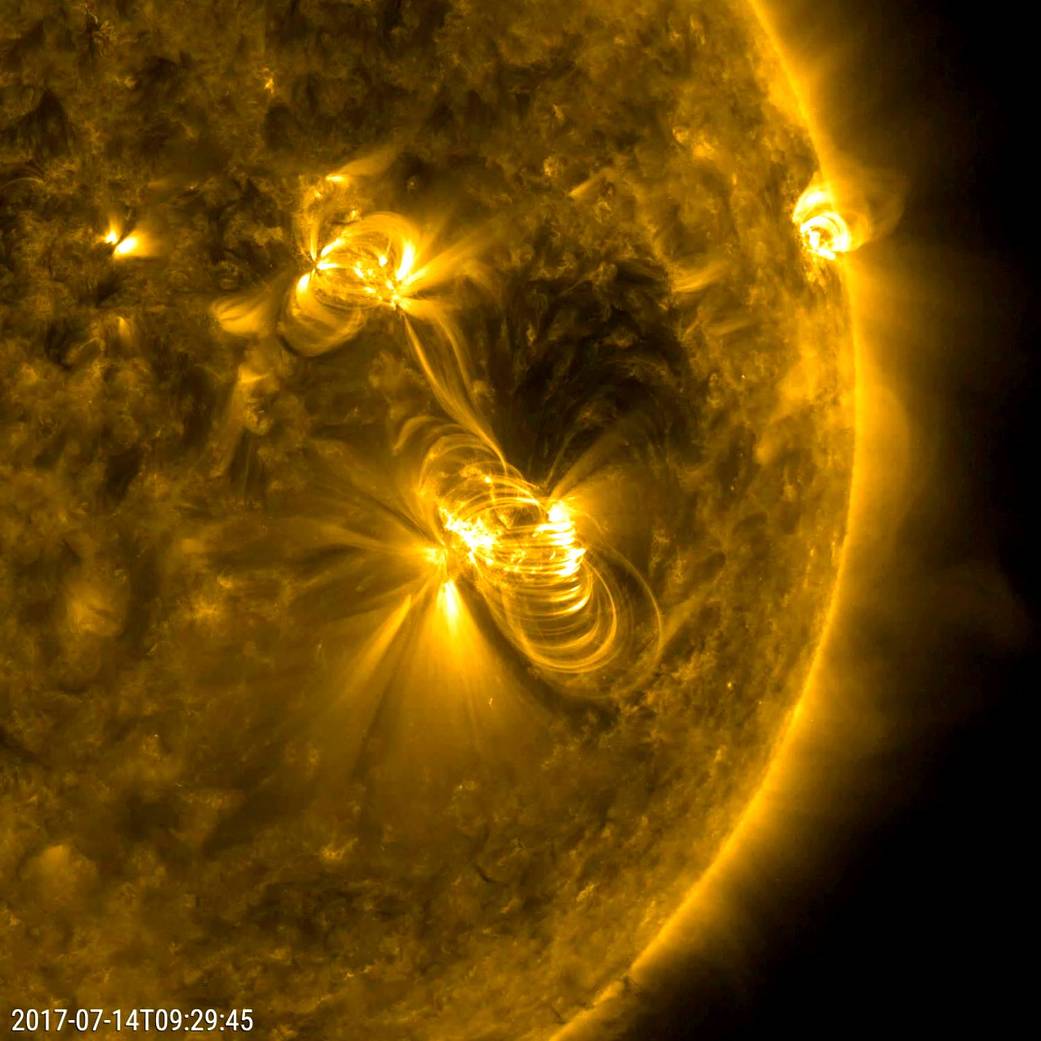

Radiation Protection

During any mission, crewmembers face threats of ionizing radiation from a variety of sources. Technical requirements outlined in NASA-STD3001 state that individual crewmember’s total career effective radiation dose during spaceflight radiation exposure is not to exceed 600 millisieverts (mSv). Additionally, short-term radiation exposure to solar particle events is limited to an effective dose of 250 mSv per event to minimize acute effects. Design choices and shielding strategies can be implemented to reduce the threat posed by radiation and ensure crew safety and health.

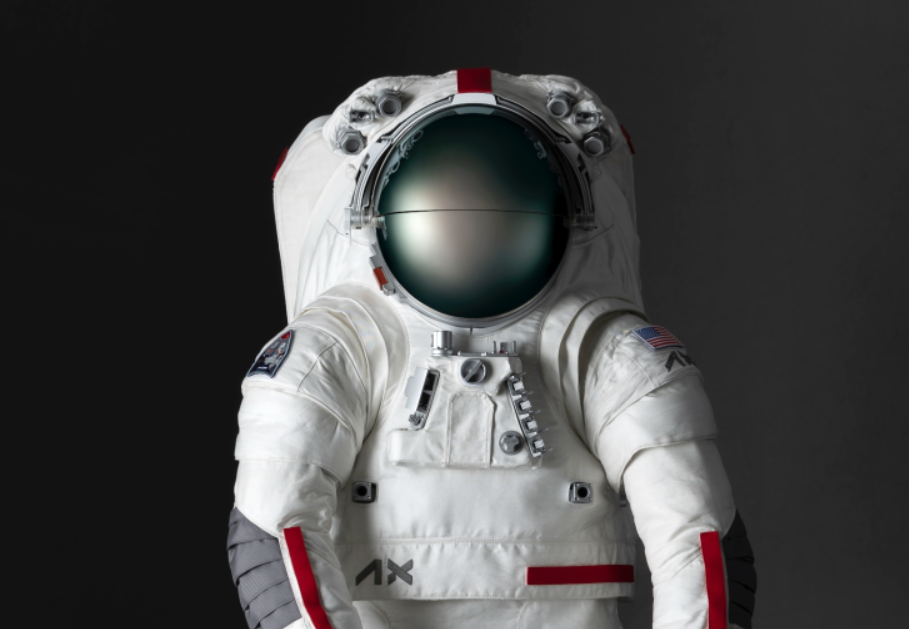

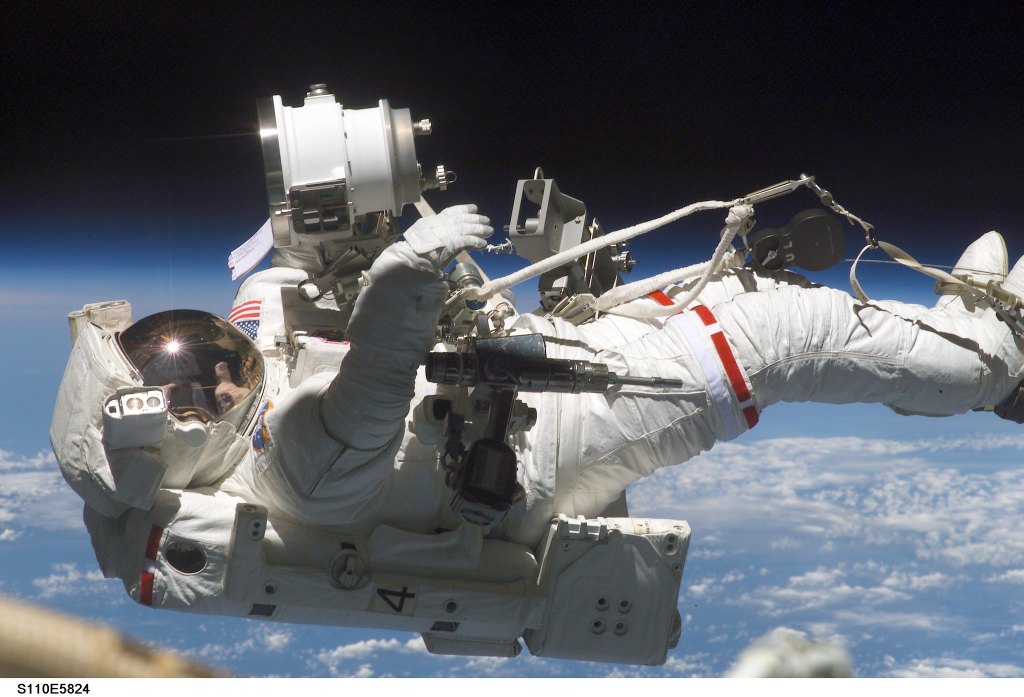

Spacesuits

Spacesuits are vital to provide a self-contained habitable atmosphere to sustain human life and meet crew health, safety, and performance needs throughout a suited mission. Suited activities are an essential part of human spaceflight, enabling astronauts to work in hazardous environments that are otherwise uninhabitable to humans. These include extravehicular (EVA), such as EVAs outside the International Space Station and planetary surface missions, and Launch, Entry, and Abort (LEA) or intravehicular (IVA) activities. Each type of activity requires a different level of support needs and performance functionality, providing the same life support functions as spacecrafts including oxygen and pressure, carbon dioxide removal, temperature and humidity control, food and water provisions, and the collection of human waste. Suited activities allow many aspects of mission science, exploration, and maintenance. Additionally, it is important for vehicle designers to understand and account for the interfaces between vehicle systems and spacesuits. These human system requirements should be reviewed for consideration of the suit-to-system interface.

Suited Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

This technical bulletin provides updates to verification testing recommendations listed in NASA-STD-3001 Volume 2 [V2 11039] Nominal Spacesuit Carbon Dioxide Levels. This update is focused on the changes to measurement and verification methods and does not address or assume any changes to the physiological exposure limits as listed in the standard.

Touch Temperature

Exposure to either extreme heat or extreme cold, form whole-body exposure or contact with hot or cold surfaces, can be dangerous to crewmembers. Hot or cold surfaces are safety hazards due to the risk of touch exposure causing performance decrements and an inability to handle an object and/or numbness, ultimately leading to damage and illness (infection) of the skin/tissue. The sensation of the temperature of an object depends on the type of material that is touched and in some cases on the perception of injury by the human. An analysis utilizing test data can be preformed to determine the lag between the object temperature and skin temperature, which is one of the controls for both critical and catastrophic hazards related to touch temperature.

Usability, Workload, and Error

An iterative design approach that considers critical and complex tasks the crew must perform should be thoroughly tested with human-in-the-loop testing. The goal is to minimize errors, ensure crew usability and right size workload to enable crew performance and mission success. Early and iterative testing in the design cycle will identify issues to minimize requirement non-compliance and design changes later in the cycle when they are more expensive to implement and can cause significant schedule impacts.

Vehicle Hatches

Perseverance, nicknamed Percy, is a car-sized Mars rover designed to explore the crater Jezero on Mars as part of NASA’s Mars 2020 mission. It was manufactured by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and launched on 30 July 2020, at 11:50 UTC. Confirmation that the rover successfully landed on Mars was received on 18 February 2021, at 20:55 UTC. As of 31 August 2021, Perseverance has been active on Mars for 189 sols (194 Earth days) since its landing. Following the rover’s arrival, NASA named the landing site Octavia E. Butler Landing.

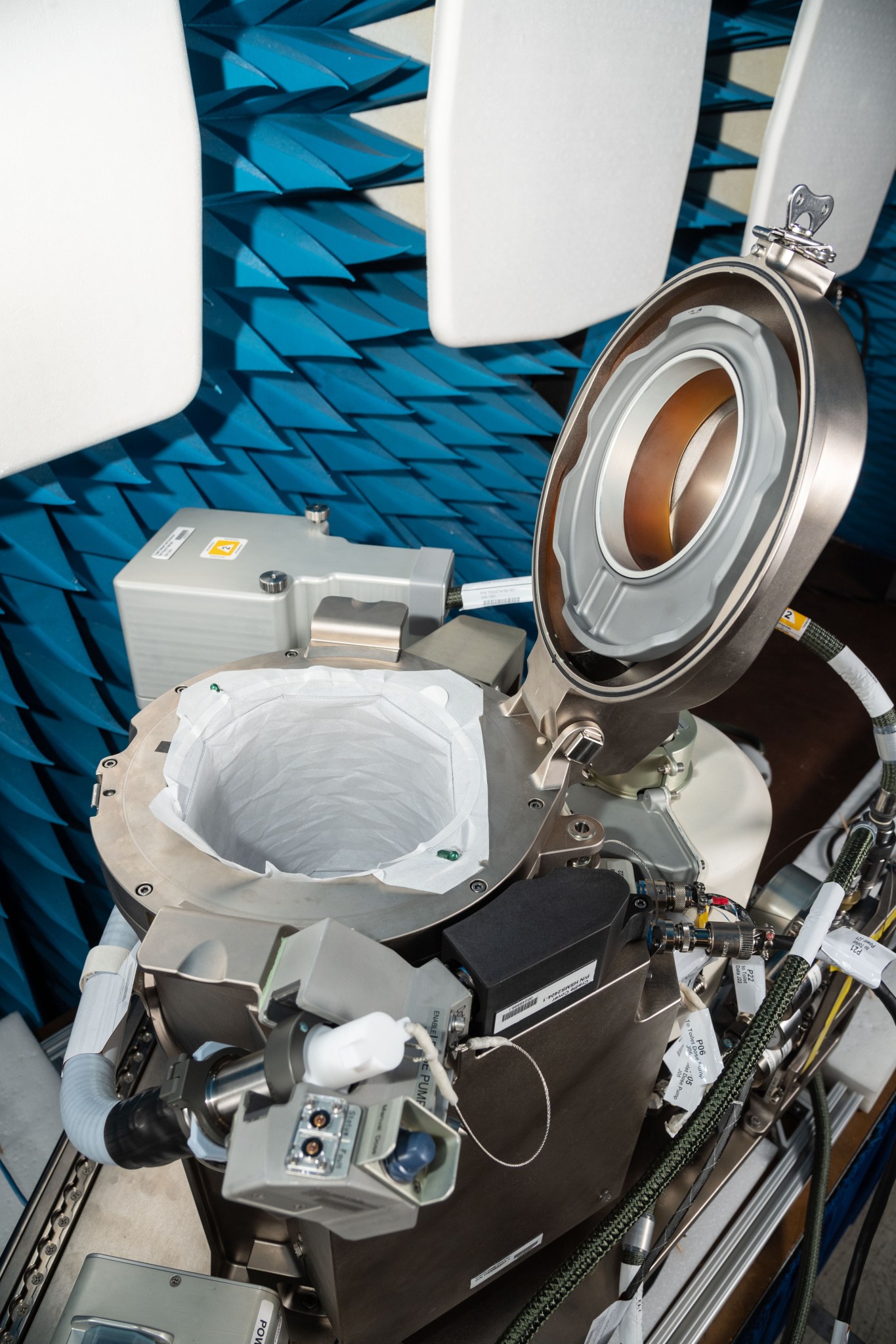

Waste Management

During spaceflight, proper elimination and containment of human waste (feces, urine, menses, and vomit) and related hygiene items is critical to consider when designing habitable volumes and capabilities for the crew. This should also include the periods of time when the crew will be suited for various activities or phases of the mission/flight. The waste management collection system and related products must be capable of collecting and containing maximum values of all forms of human waste. ue to the close quarters and time spent in both microgravity and partial gravity, body waste and odors can be difficult to contain. Contamination from body waste can enter the body through the eyes, nose, mouth, ears, and cuts in the skin, which can lead to a variety of illnesses and infections.

Additionally, microgravity conditions can cause unintended free-floating waste that can inadvertently (and unknowingly) soil a crewmember. Methods to prevent cross-contamination need to be considered during the vehicle design process. These methods may include isolating the body waste system from the personal hygiene areas and the food system, maximizing the distance between the systems, and employing appropriate cleaning and filtering techniques.

More Technical and Medical Brief Collections

Fundamentals of Human Health

Astronauts traveling in space are faced with both common terrestrial and unique spaceflight-induced health risks. The primary focus of NASA medical operations is to prevent the occurrence of inflight medical events, but to be prepared to provide robust clinical management when they do occur. Inflight medical systems face several challenges, including limited stowage capabilities, potential disruptions in ground communication, exposure to space radiation, and limitation of some functional capabilities in a microgravity environment.

Medical Operations and Clinical Care

NASA emphasizes the importance of comprehensive astronaut health. Considerations for the protection of astronaut health spans a continuum across a mission, including requirements for selecting a healthy crew, preparing the crew for a mission, and continuing to monitor and rehabilitate the crew postflight.

Safety, History, Contingency & Mishaps

Spaceflight vehicles designed for human habitability must follow design considerations that accommodate the daily functions of the astronauts living onboard, including dining, sleep, hygiene and waste management, and other activities to ensure an efficient and healthy environment.