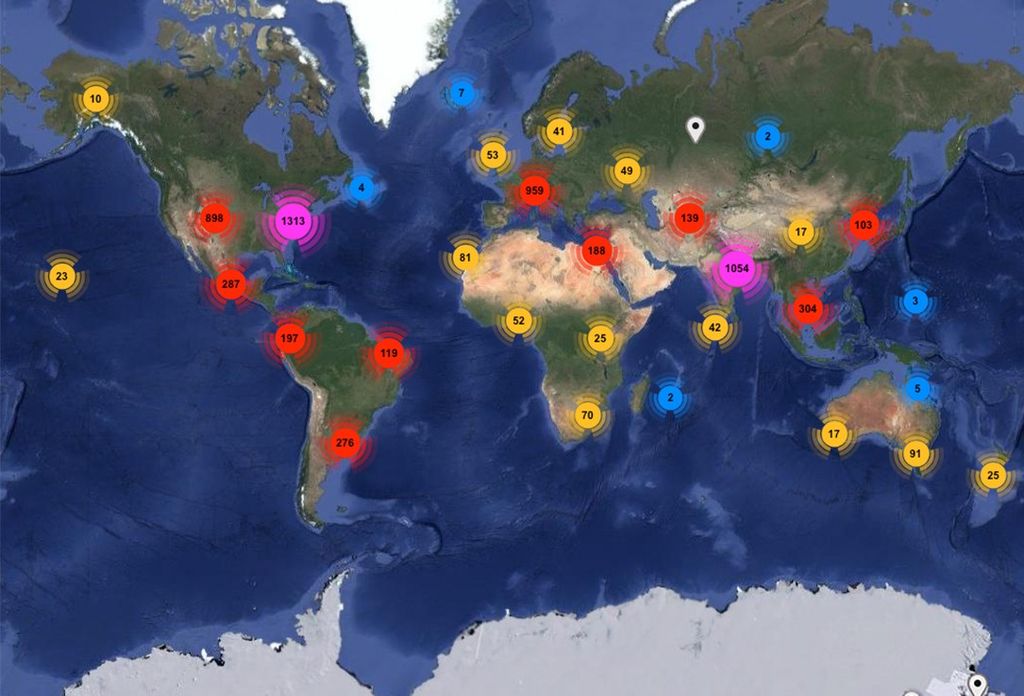

Andres Almeida (Host): There’s a program at NASA that taps into the power of the public to solve some of the toughest problems in space exploration. It’s called Centennial Challenges, a prize competition that has awarded more than $24 million to hundreds of people ranging from academics, startup founders, small business owners, and independent inventors from across the U.S. and 86 countries.

For 20 years, these prize competitions have opened the door for teams to bring bold ideas to NASA. In some cases, these ideas spin off into real technologies shaping missions today, like 3D-printed habitats, robotics, and sustainable food for long-duration missions to deep space.

In this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, we talk with Savannah Bullard, strategic communications lead for NASA’s Centennial Challenges Program Office out of Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. We’ll talk about how competitions fuel science and engineering breakthroughs, what it takes to design and judge them, and how you can participate.

This is Small Steps, Giant Leaps.

[Intro music]

Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, the podcast from NASA’s Academy for Program/Project & Engineering Leadership, or APPEL. I’m your host, Andres Almeida.

Centennial Challenges is an exciting program and we’re glad Savannah is here to tell us more about it.

Host: Hey, Savannah, good to have you here.

Savannah Bullard: Thank you for having me.

Host: Can you tell us a bit more about Centennial Challenges and what role does the program play with NASA’s broader mission?

Bullard: Absolutely. So, NASA uses prizes, challenges and crowdsourcing as a complementary way to really help maintain and advance America’s leadership in tech and in innovation. We do this through two avenues. We have the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation, which we shortened to CoECI, and then we have Centennial Challenges.

CoECI differs a little bit because they rely heavily on vendors to execute quicker, smaller-dollar challenges of interest to their respective customers and clients. So, it’s a little bit more of a collaborative approach, hence their name.

Centennial is very in-house. We are NASA’s flagship in-house competition program. We deal in multimillion-dollar competitions, and these are managed and executed entirely through our office. And we have the support of allied partners, but we largely own them.

Our program was initiated in 2003 from a congressional amendment to the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958. So, Congress basically went and said, “We want a prize authority that can interface with the public and encourage a bigger flow of innovative ideas to NASA.” This was back in the early 2000s, and 2003 actually marked 100 years since Orville and Wilbur Wright flew their first aircraft in North Carolina. With that 100 years, the spirit of innovation, the discovery, that inspired the name Centennial Challenges.

Our first challenge launched in 2005 so we’ve been running challenges officially for the Agency for 20 years, and in that time, we’ve done a lot. We’ve executed 23 competitions awarded more than $23 million in prize funds. We work largely with NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate and designed challenges around topics that supports the agency’s goal of returning humans to the Moon and journeying to Mars. So, there’s a lot we’ve got going on over here.

Host: Yeah, it seems like it doesn’t stop, huh?

Bullard: Never!

Host: Can you highlight some of the technical areas where Centennial Challenges has driven the most significant breakthroughs?

Bullard: Absolutely. I always say that our colleagues around the agency are working on the big stuff, and this can be anything from NASA Space Launch System to human landing systems, propulsion satellites, telescopes, the things that you hear about all the time. Centennial focuses on some of the smaller details that could benefit from novel concepts like spacesuits or robotics, science instrumentation, nanotech, those types of corners of NASA that you’re not thinking about all the time when you initially think of NASA.

So, our program really demonstrates the significance of diversity of thought and the power of heterogeneous thinking to find technical solutions. And we have made some really cool breakthroughs.

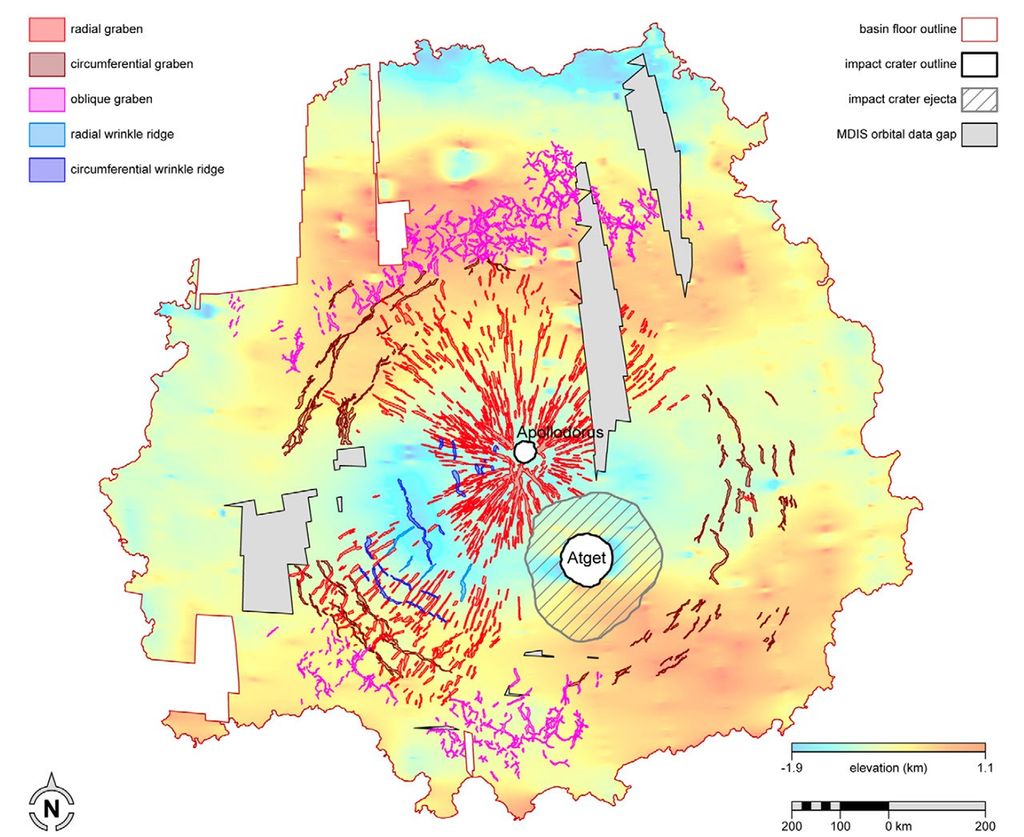

One of my favorite challenges that we’ve done was called the 3D-Printed Habitat Challenge. This was where we were looking for automated 3D-printed technologies that could actually print housing using in situ resource utilization, or ISRU. We basically wanted to be able to take a robot, more or less, and stick it on the Moon or Mars and use the regolith that is available on the Moon or Mars as a feedstock for 3D printing. And it needs to do this completely and autonomously, so that by the time a human gets to the Moon or Mars, they’ve already got accommodations. That was a wildly successful challenge. It did extremely well.

One of the teams from that challenge (they were called ICON) I believe they were working closely with the Colorado School of Mines. On this one, they had to actually drop out of the competition, because they were getting so much commercial success and their technology was so successful and important that they actually ended up 3D printing, building the CHAPEA habitats that we use for analog missions now at NASA.

Another really cool challenge that we did was a vascular tissue challenge, where we were trying to see if we could basically create vascular tissue and Wake Forest University, they participated in that challenge through two different teams, ended up winning, and now they’re sending stuff to the International Space Station to be tested through ISS National Labs.

So, we never guarantee work with NASA, but it just goes to show that by selecting an idea very strategically and making sure that it aligns with NASA’s goals and their initiatives, we see a lot of these teams end up coming back and then contributing to the agency in a really big way.

Host: How do Centennial Challenges differ from traditional NASA research development projects?

Bullard: This is one of the things that I love about Centennial, because it is so unique, and you don’t see this really in any other parts of the agency, NASA benefits from public crowdsourcing, because we’re able to solicit solutions and test them to a varied degree of technology readiness and incentivize individuals to continue developing those solutions, all from our own little program and completely separate from NASA’s greater R&D resource pool.

Rapid prototyping allows our teams to fail fast and approach solutions with an iterative mindset, and so they can only improve and we only also competitors are not supported by government funding, and awards are only made to successful teams when challenge requirements are met. So, we are only rewarding success. And so that allows our teams to be a little bit more daring with their prototyping and with the advancement of their technologies, and then they are rewarded in kind.

But there are two things that I think make Centennial really unique, and that is that the prizes we give, these are not grants or contracts or anything. This is purely a prize. But we do see a lot of what I like to call repeat customers, cheekily, because we do see a lot of teams come back and continue to iterate and continue to advance their own technologies through a variety of different challenges.

The other thing is, Centennial and NASA, we never claim intellectual property rights from teams. They maintain all of their intellectual property. So, we’re not going to take an idea from a team and then go develop it ourselves or try to take a certain solution and integrate it into greater NASA systems. This is purely their ideas and their solutions, and that gives our teams the opportunity to go and apply for patents or publish white papers or get other contracts.

And we do see them end up coming back and working with NASA a lot, but some of them will go start their own companies and find success that way. So, really, we’re just a foot in the door to the greater innovation space, the greater space technology arena. And so, being able to kind of have that foot in the door is one of the biggest draws of Centennial, it’s almost like the prize money isn’t even the biggest incentive there is. There’s so much room for opportunity.

Host: How are teams generally evaluated during a Centennial Challenge?

Bullard: It’s a really good question, and one that really starts to be answered at the very beginning of a Challenge’s conception.

From an initial brainstorm to official launch, it takes up to a year to get a challenge off the ground. Much of that year is spent developing rules and criteria for how exactly we can define a successful solution. So, we’re trying to think about what a great solution looks like from the jump. We don’t want to set teams up for failure. So, this involves soliciting a lot of feedback from subject matter experts from within NASA and then across the federal government, commercial industry, and academia.

The entire time, we are constantly working with great groups of people and leadership across NASA’s different mission directorates and agency leadership to ensure that challenges we’re running will actually be successful and of good use to the agency. So, once a challenge is launched, we’re pretty confident that we have a wide-reaching arm of support, and we know what a successful solution is going to look like. Because, I mean, if we don’t have a good idea of what we’re actually looking for, how can we ever award a significant amount of prize funds to a team?

So, once we have that north star picked out, we develop rules and guardrails for teams to reach for that goal. At the same time, we’re hand-picking judges from within and outside of NASA to volunteer their time and expertise during our evaluation periods. So, all of this is happening concurrently, and then when it’s time for judging, they receive scoring rubrics and judging guidelines that we create based on the info gathering we did during challenge development, and then they apply their knowledge to determine the most successful solutions.

So, it very much varies between challenge to challenge, but mostly it’s because we have thought with some of the brightest minds that we can find about what a successful solution actually looks like. So, it’s very involved. It’s very meticulous. But when you’re dealing with such an incentivizing opportunity, you really want to make sure you’re rewarding true success and encouraging the right solutions to progress. And we can’t make those determinations alone, so we truly stand on the shoulders of giants when it comes to that.

Host: So what have been some of the biggest technical hurdles that teams have faced, and how has NASA used those lessons to refine and even shape future challenges?

Bullard: This is so important to us because in order to define a successful solution, we have to actually be able to test it.

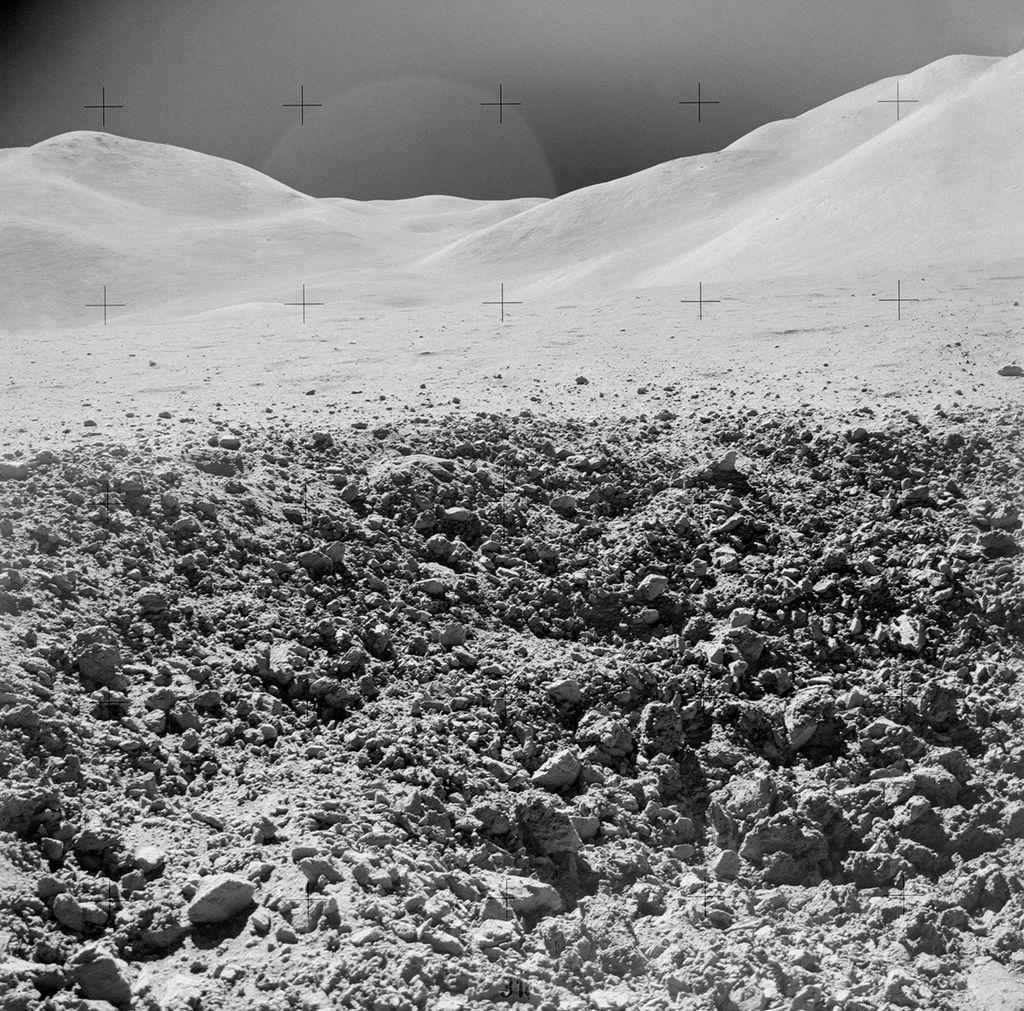

One of the stories that I love is last year, when we were hosting Break the Ice (that was our lunar excavation challenge), we were looking for robots that could excavate lunar regolith at the lunar South Pole. It’s very icy. It’s like compressed concrete. Basically, at that point, we needed robots that could excavate that regolith and then transport it so we could do ice extraction and things like that, so we can use the water that is to be found at the lunar South Pole.

So, during that competition, at the very end, we had teams that had prototypes that were ready to be tested, but we had to try to find a way to simulate lunar gravity, which is about a sixth of gravity that we find on Earth. So, we had to basically figure out how to counteract weight with the robots and make sure that we could get a really accurate reading of whether they could operate in lunar gravity.

And so, what we did is we used a crane to basically hold the robots up just enough to where the weight would be, what it would be on the Moon while they were excavating these concrete slabs that we had poured and compressed to be as close to lunar regolith as we could get it.

All of that to say, it looked a little hokey and it was a little out of the box, but Centennial very much deals in out-of-the-box ideas, and this has led us to really think critically about the testability of solutions.

But from that, we also learned that awarding test opportunities allows teams to advance their tech to higher TRLs, or technology readiness levels. When a team enters a Centennial Challenge in phase one, they’re typically at TRL-1, which is just a design concept, a paper, an idea.

So, the team that I mentioned before who won second place in that Break the Ice challenge (the one who ended up hiring the college students from the third-place team), part of their incentive was they got to revisit Marshall Space Flight Center, which is where Centennial is housed, and where we held the Break the Ice competition here in Huntsville, Alabama. They were able to come back and test their technologies in our thermal vacuum chambers. That was part of their prize just beyond the money.

And so, they started Break the Ice in phase one at a TRL level of one, and by the time they came and tested in our thermal vacuum chambers, they were at a TRL level of six.

So, we’re creating more incentives beyond the prize funds, and finding different ways to support that iterative, rapid prototyping of technologies. So, it’s always a little bit of a shift and an adjustment, but if we’re not being innovative, then we’re not staying true to the program. So, it’s very on brand for us to do that.

Host: What kind of challenges or technology gaps are you most excited about to see addressed in the coming years?

Bullard: So, we will always defer to our leadership when choosing topics to build challenges around. But I’m most excited to see the completion of two challenges currently at the forefront of the program, and that’s the LunaRecycle Challenge, and then a new challenge that I am going to kind of tease here in a moment.

But first for LunaRecycle, this is a really great challenge that we have been running since 2024. it’s a three-million-dollar, two-phase competition focused on developing solutions that can transform trash items into useful feedstocks or end products on the surface of the Moon and Mars. So, we’re looking at items like clothing or food packaging, structural elements, plastic bags, nitrile gloves, things that just kind of accumulate – what you would truly think of when you think of trash.

We want to basically find innovative ways to recycle or reuse those waste items so that we are not piling up trash when we’re on the moon or on Mars or trying to send it back to Earth or something like that. We really want to find a way to make everything we bring with us on these long-duration missions work beyond their initial use. So, we finished phase one this spring and awarded $850,000 and phase two is currently in motion and is set to conclude next summer. We’re going to be awarding up to $2 million in this final phase. And currently phase two is still open to us participants. So, if anybody wants to join LunaRecycle, now is definitely the time.

But then also coming very soon, we’re launching somewhat of a spinoff of a challenge that we concluded last year. That challenge was called the Deep Space Food Challenge. This competition focused on building regenerative technologies that transform the ways that we think about feeding astronauts. So, when we eventually send humans to Mars, we can’t rely on the largely pre-packaged meals that require frequent resupply. That’s what currently feeds our astronauts on the International Space Station. It’s a lot of pre-package and a lot of resupply. We can’t use those strategies, so we have the Deep Space Food Challenge.

Successful solutions from that challenge included prototypes that support crop growth, rearing and harvesting insects for consumption. There was fermentation, zero-gravity ovens, transforming carbon dioxide into nourishing proteins, and so many other amazing ideas. It was truly some of the best work I have seen during my time in the program.

Host: It got quite a bit of press as well.

Bullard: It did! One of the things that everybody can get behind is food, and so we did see a lot of mainstream success from that. We had celebrity chefs who were very interested in this work. This was also the first challenge that we’ve ever ran in parallel with another space agency. So, the Deep Space Food Challenge ran in parallel with the Canadian Space Agency’s version of the challenge. So, we were able to do some really cool stuff and reach a much bigger scale than what we’ve seen in the past.

What we learned from all of that success is that all of those components that did extremely well were just components. They’re fragments of a solution that will need to work within a bigger, more complex system. So, we’re building on that success with a single-phase competition and it’s going to focus on incentivizing a complete space food system for planetary surface missions. So, we want those food systems to integrate a variety of food sources and technologies that meet 100% of an astronaut crew’s variable nutritional needs.

We would also love to see solutions from this challenge integrate an environmental control and life support system or ECLSSs, because we want some closed loop resource utilization, and we also want to see if it can sustain operations for a hypothetical astronaut crew of 10 to 15 people for five years. So, we’re really going for the gold with this challenge to see, basically, how can we take the components that were so successful from deep space food and put them into one complete integrated system? So that’s slated to potentially open this fall, and I’m very excited to see what comes of that.

Host: I am very excited too. How can people get involved? Like, how can, say, a project manager or NASA engineer become involved? Or how can somebody join a team to submit their ideas, things like that?

Bullard: That’s a really great question. You know, we really rely on crowdsourcing and grassroots efforts to make sure that we are staying true to our mission of being a public prize competition program. And so, for teams who might want to get involved in our competitions, I would encourage them to go to nasa.gov/winit (w-i-n-i-t). That is the best way for them to see our entire portfolio of challenges that are currently open. They can also take a look at past challenges as well as see what might be coming up in the future.

As for NASA, folks who might want to be a judge or a subject matter expert or collaborate on a challenge idea, I would say, reach out to me and we can collaborate with our programs and see if we can make some more magic soon.

Host: Excellent, yeah. Finally, Savannah, what was your giant leap?

Bullard: That’s such a good question. The biggest thing for me kind of went back to my education. I was horrible at science when I was in school from kindergarten all the way through college, I was terrible at science, and I grew up in Huntsville, Alabama. I’ve always known Marshall Space Flight Center. NASA is in my backyard. I’m literally from the Rocket City, and I never thought of it as a potential career opportunity, because I was just not good at science.

But I was very good at communicating and the written word and being an overall conveyor of ideas, and I could find that I was really good at that, and so I pursued a career in communications and media, which has led me all over the place, and I’ve done some really amazing things. But then I ended up finding my way back home, and now I communicate science.

And I have a lot of imposter syndrome in this job, I’m not gonna lie. But the biggest thing that I have to tell myself is I get to work with literal rocket scientists, where their subject matter expertise is the science and technology that they do every day. My subject matter expertise is how to communicate that to the public, how to make people care about it, and how to get people involved.

Host: That is very relatable. I appreciate that candor there. Savannah, thank you so much for your time. We learned a lot today.

Bullard: Thank you so much for having me, and I can’t wait to see what we all do next.

Host: That wraps up another episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps. For a full transcript of this episode, and to hear past episodes with fascinating people from across NASA, visit nasa.gov/podcasts. While you’re there, you can also check out our other podcasts like Houston, We Have a Podcast, Curious Universe, and Universo curioso de la NASA. As always, thanks for listening.

Outro: This is an official NASA podcast.