When a plane overshoots the final approach, often the pilot’s natural — and dangerous — instinct is to pitch the aircraft up to slow down and land. It’s one of the leading causes of accidents, especially with small airplanes.

But what if that same mistake happened at 5,000 feet instead?

A new virtual reality tool developed in cooperation with NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, can help pilots train for these scenarios in real life — with far less danger.

Pilots have long been training on virtual reality simulators on the ground, but these have limitations. For one thing, “there’s not a lot of fear factor, because you’re not really doing it. You screw up, you hit the reset button, you try again,” says Bruce Cogan, an aeronautical engineer at Armstrong.

Also, he says, the simulator is only ever as good as its programming. “It’s challenging to replicate how the aircraft feels. You may be training a pilot to land, but if the dynamics of the simulation aren’t very good, it’s not going to be very useful and could even be harmful.”

The simulator hooks into any airplane and, with the aid of virtual reality goggles, layers a virtual scene over the real world outside the cockpit. “You actually get the dynamics of the exact airplane you’re flying,” Cogan says.

And with a virtual runway created by the software, “you can train for this landing task at 5,000 feet, so if you mess up, you won’t hurt the airplane. You can go try again.”

What’s the Cue?

NASA’s initial interest in the platform wasn’t for training, Cogan explains, but for evaluating how well an aircraft performs, part of the agency’s core work to improve the technology of how we fly. Cogan’s project was looking to answer the question of “when [a pilot] puts in a control input, does the airplane do what he wants? Is it too slow? Too fast?”

Testing those maneuvers requires actually flying the aircraft, and that can be an expensive proposition. For example, refueling an aircraft while flying not only requires a second fuel-carrying airplane — an added cost — but also carries the risk of a collision, even with an experienced pilot.

With a virtual reality platform, however, the second plane can be simulated.

Cogan began working with Hawthorne, California-based Systems Technology Inc. (STI) under Small Business Innovation Research contracts to adapt a system the company first developed for the military as a ground-based simulator that hooked into real aircraft.

The biggest challenge, explains STI CEO David Landon, was figuring out how to cue the technology on what should be visible and what should be overlaid with the virtual scene. On the ground, they used color, much like a green screen for a television weather map. But NASA wanted the pilot to be able to see the real view outside the windscreen, so they had to develop a new system that cued off of brightness and infrared light.

Virtual Surgeon on Mars

The beauty of the platform, branded Fused Reality, is that “going forward, every aircraft can become its own simulator,” Landon says. Pilots and airplane developers can test and practice maneuvers in real conditions with just one system that uses inexpensive, off-the-shelf components and can be moved from one plane to another and even to a helicopter.

Fused Reality also reduces the need for additional equipment and personnel during training, whether it’s the tanker plane in aerial fueling or a person in the water in a helicopter rescue.

STI has been in talks with airplane manufacturers interested in using Fused Reality both to evaluate their planes — and to potentially use it as a marketing tool, allowing them to “show off” how the plane performs in high-risk conditions. They are also interested in using the tool to help design features like a heads-up display, a transparent screen that displays flight data across the windshield that pilots can see without looking down. With the virtual reality tool, tweaks can be tested without the cost of rebuilding the display every time.

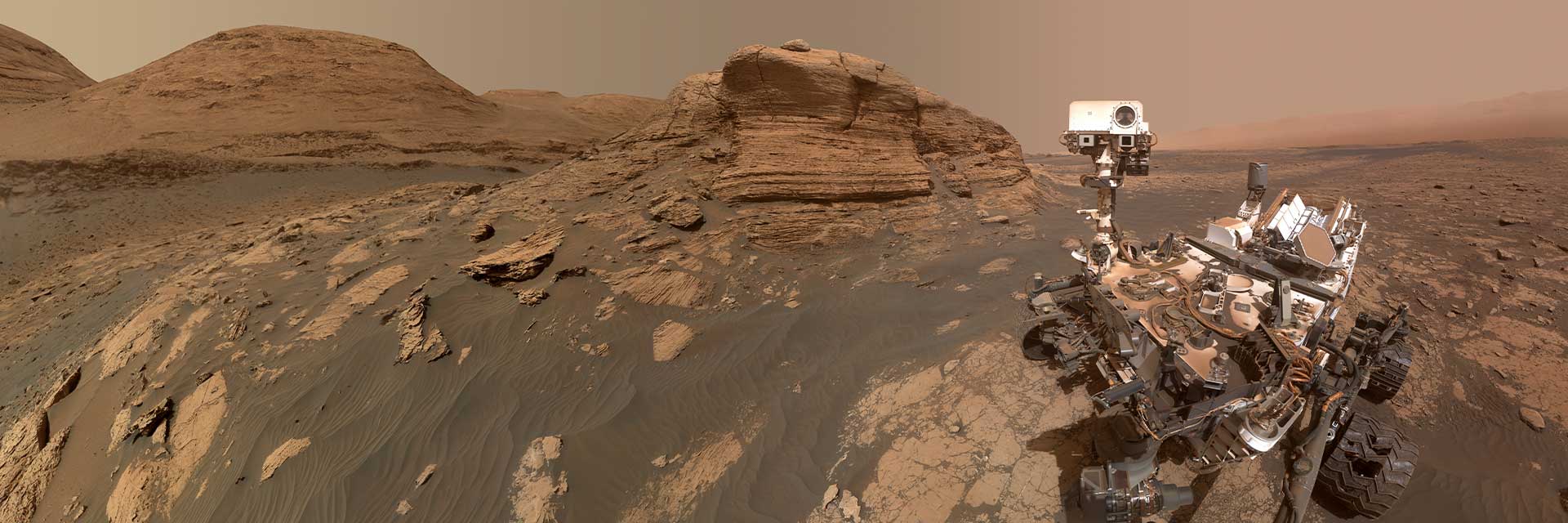

Looking forward, Cogan says, NASA sees applications for longer-duration voyages, like to Mars, where the Fused Reality simulator could show diagrams that overlay broken hardware to help repair it, or even provide visual aids for surgery or other medical procedures.

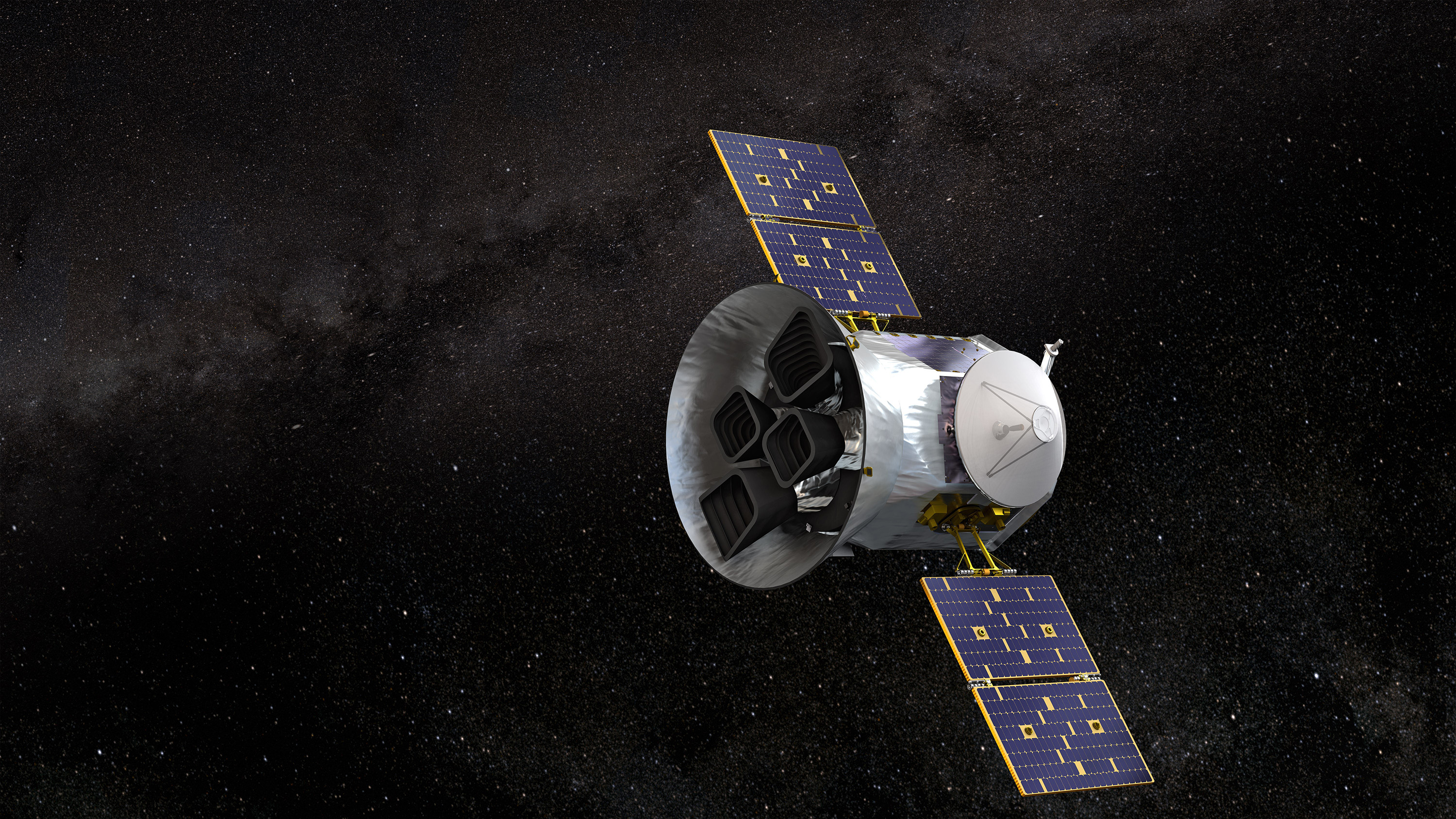

NASA has a long history of transferring technology to the private sector. Each year, the agency’s Spinoff publication profiles about 50 NASA technologies that have transformed into commercial products and services, demonstrating the wider benefits of America’s investment in its space program. Spinoff is a publication of the Technology Transfer program in NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

To learn more about this NASA spinoff, read the original article from Spinoff 2018.

For more information on how NASA is bringing its technology down to Earth, visit http://technology.nasa.gov.

Naomi Seck

Goddard Space Flight Center