Dummies strapped into their seats. Check.

Instrumentation and cameras hooked up. Check.

Helicopter fuselage ready for lift. Check.

After more than two years of preparation and collaboration between NASA, the U.S. Navy, U.S. Army and Federal Aviation Administration, the day had finally come.

Thirteen instrumented crash test dummies and two un-instrumented manikins stood, sat or reclined for a potentially rough ride – the Transport Rotorcraft Airframe Crash Testbed full-scale crash test at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

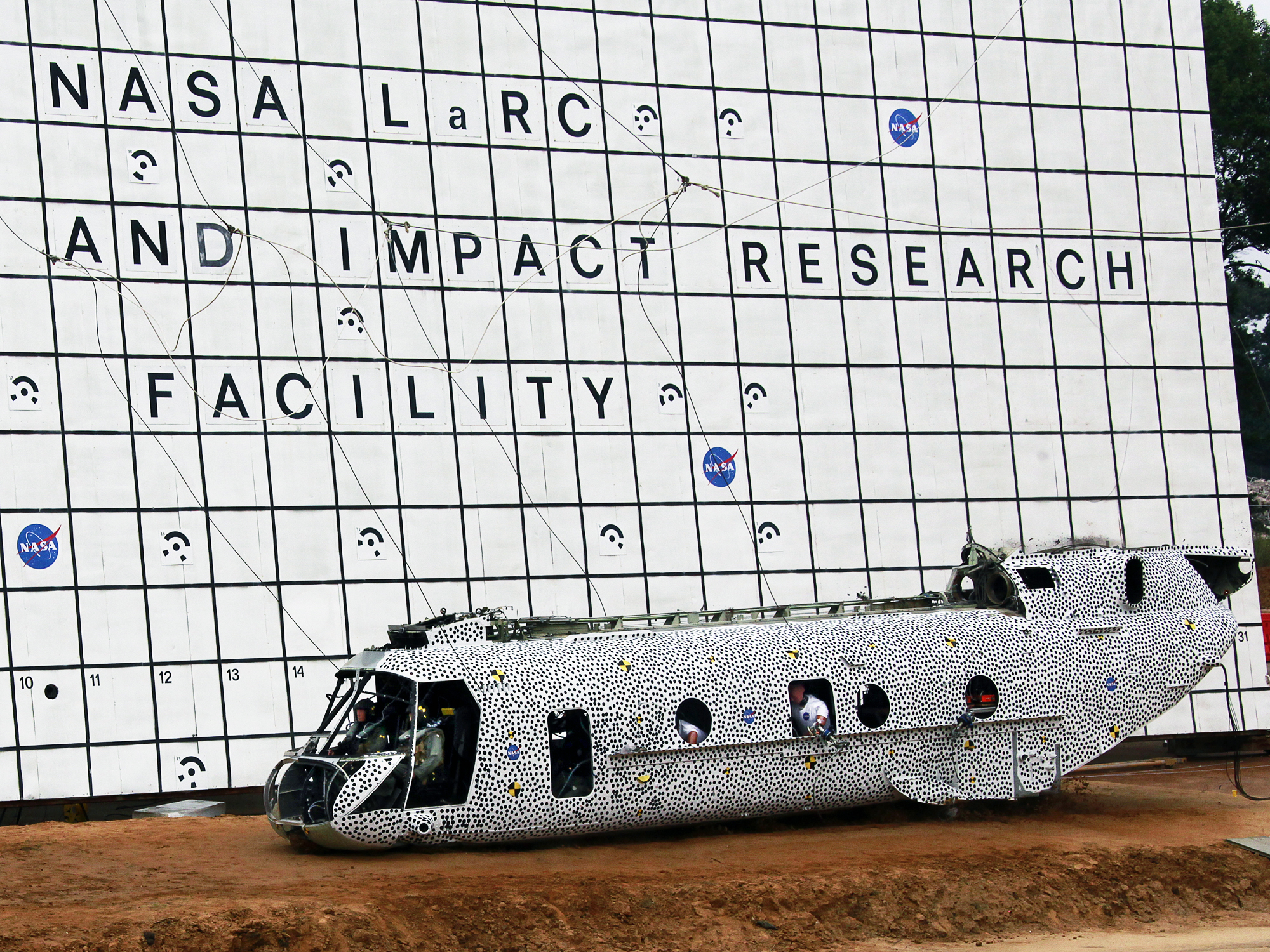

“Three, two, one, release,” said engineer Richard Boitnoitt on the loudspeaker at NASA Langley’s Landing and Impact Research (LandIR) facility. With that countdown the 45-foot-long former Marine helicopter fuselage smacked into a bed of soil, its 15 occupants violently jolted all in the name of research to try to make helicopters safer.

“We designed this test to simulate a severe but survivable crash under both civilian and military requirements,” said NASA lead test engineer Martin Annett. “It was amazingly complicated with all the planning, dummies, cameras, instrumentation and collaborators, but it went off without any major hitches.”

Cables hauled the helicopter fuselage to a height of about 30 feet and then swung it to the ground, much like a pendulum. Just before impact, pyro-technic devices released the suspension cables from the helicopter to allow free flight. In “engineer speak,” the chopper travelled at “35 feet per second horizontal and 26 feet per second vertical.” In everyday language, it hit the ground at about 30 miles an hour.

Almost 40 cameras inside and out, and onboard computers with 350 data channels, recorded every move of the 10,300-pound fuselage and its “passengers.” Even the helicopter’s unusual black-and-white-speckled paint job contributed to the data collection. It was for a photographic technique called full field photogrammetry.

“High speed cameras filming at 500 images per second tracked each black dot, so after everything is over, we can plot exactly how the fuselage deformed or reacted under crash loads,” said NASA test engineer Justin Littell.

The fuselage appeared to survive better than some of the occupants. The data will take months to analyze but initial observations indicate many of the dummies suffered what would have been severe injuries if they were humans.

The goal of the drop was to test improved seat belts and seats, to collect crashworthiness data and to check out some new test methods. But it was also to serve as a baseline for another scheduled test in 2014.

A crash test of a similar helicopter airframe equipped with additional technology, including composite airframe retrofits, is planned for next summer. Both tests are part of the NASA Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate’s Fundamental Aeronautics Program Rotary Wing Project.

NASA will use the results of the crash experiments to try to improve rotorcraft performance and efficiency, in part by assessing the reliability of high performance, lightweight composite materials. Researchers also want to increase industry knowledge and create more complete computer models that can be used to design better and safer helicopters.

The Navy provided both CH-46E Sea Knight helicopter fuselages. For this first test it also contributed seats, five crash test dummies, one manikin and other experiments. The Army provided a manikin and a crash test dummy that was lying much like a patient in a medical evacuation litter. The FAA provided a side facing specialized crash test dummy and part of the data acquisition system. Cobham Life Support-St. Petersburg, a division of CONAX Florida Corporation, also contributed a retracting restraint system for the cockpit. NASA Langley added six of its own dummies as well as lead technical expertise and the LandIR facility and crew.

LandIR, a 240-foot high, 400-foot long gantry, has an almost 50-year history. It started out as the Lunar Landing Research Facility, where Neil Armstrong and other astronauts learned to land on the moon. Then it became a crash test facility where engineers could simulate aircraft accidents. And recently it added a big pool where NASA is testing Orion space capsule mock-ups in anticipation of water landings.