Current Interview

Interview with Catharine “Cassie” Conley

Research Scientist, Plant Biologist

NASA Planetary Protection Officer, 2006-2018

_________________________________________________________________________________________

In the following interview, questions from the interviewer, Fred Van Wert, are in bold, and Cassie Conley’s responses are in regular text.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

I’m delighted that you agreed to do this brief interview today. Whenever we do this, I do some background checking, prepping for the interview, and I have to say you have the most fascinating background of any of the fifty plus of these we’ve done. By the way, these are archived on the web, so they are open to the public and they stay there forever, I have to remind you of that. You’re in a lab but not at Ames, is that right?

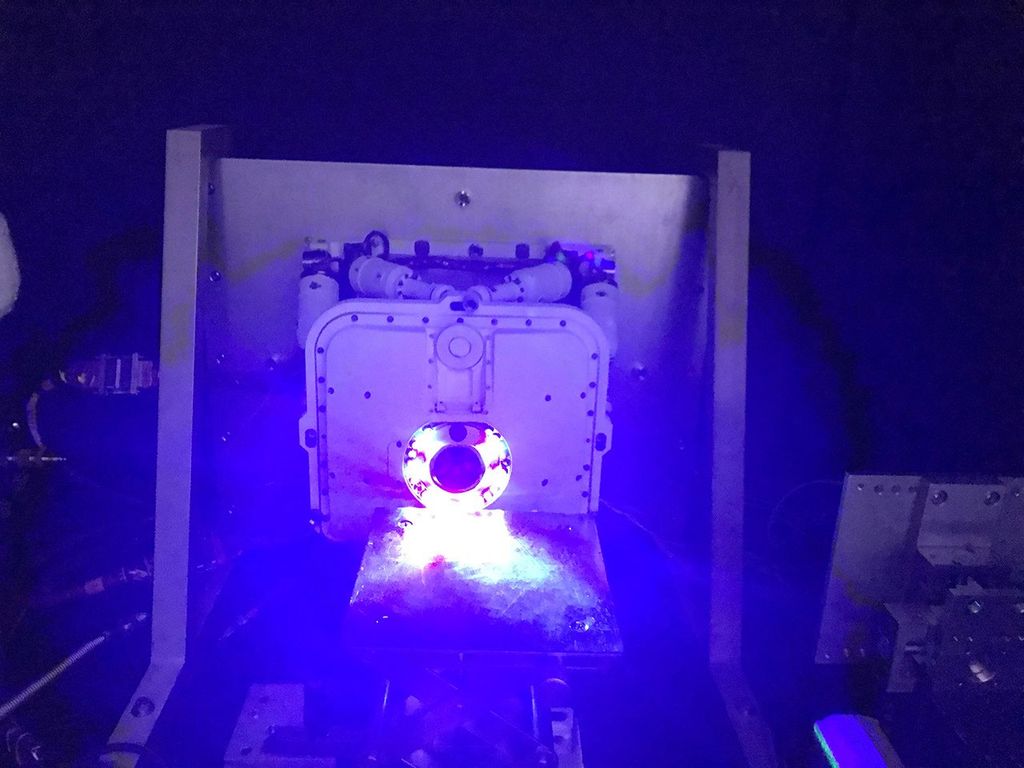

Right, I’m a visiting scientist at the Carnegie Institution in Washington D.C., where Andrew Steele is hosting me. He was on my advisory committee when I was Planetary Protection Officer. He was one of the people who worked on the Allen Hills meteorite that was reported as having fossil Mars organisms. Steele showed that all those data were equally consistent with the observations being non-biological material from Earth, or possibly Earth organisms contaminating the samples. We’re continuing some of that work with a goal of understanding how to set statistical confidence limits on whether something you just detected is really life that’s native to the sample, or not. Because if something is definitely not life, that’s just as important to know as if it is.

What a fascinating field of interest, but let’s start with your childhood, where you’re from, your family at the time, and so forth. I checked your online bio and saw that you come from technical and scientifically oriented parents. Did you inherit some of that? And how young were you when you got an inkling that you might pursue science as a career?

My dad was a mathematician; he consulted for NASA. He worked with Ames apparently, at least his name is listed in the technical report server as having published papers with people at Ames in the early ‘60s. He was consulting with the Apollo program to develop theoretical solutions for the orbital mechanics that were being used to guide spacecraft. Some of his mathematics are still being used to understand orbital mechanics and to guide spacecraft, and a lot of other things. I’ve pretty much always been a scientist — it just never occurred to me that I would not be able to work on this kind of thing, if I wanted to. That may be a different scenario than many other people who say, “Oh!” and suddenly realize “I could do science!” It never occurred to me that I couldn’t. It was just a choice between doing science or doing something else, which I had to decide in high school. I can talk about that if you’re interested.

Indeed, yes.

My mother was a biologist, a geneticist with a background in fruit flies. When I was very young my mother started me on violin lessons, so while I was doing science, I was also doing music and other artistic things, and in high school I had to choose to do science or go into music, when I applied to college. I realized that while I could probably be a pretty good scientist, it would be a lot harder for me to be anything better than a mediocre musician. That was the decision I had to make in high school: what should I be? What can I do a better job at, as my contribution to society? And clearly music was not it, as I was not as accomplished at music as I was at science. So, science was what I chose.

I read a statement about your thought process. You mentioned somewhere along the line that you had noticed that those who pursued music as an avocation seemed not to maintain the interest, or the delight, in music over time.

The joy, yes. It’s a lot harder to make a living in music. Musicians, even good musicians, don’t get paid very well unless they’re at the absolute top, whereas, you know, scientists at a pharmaceutical company are likely to make a whole lot more money, even if they’re not doing outstanding research.

That is insightful as well as practical, so excellent comments there.

Yeah, well, that is an outcome of our society that wasn’t necessarily true in other societies. I studied Russian in college and went to the Soviet Union several times before it stopped being the Soviet Union. And there, musicians and artists were paid just as well — or, rather, just as poorly — in terms of monetary income. Their value was considered equivalent to scientists, doctors, and other careers that in this country often have very different salary scales. It doesn’t have to be that way, and I don’t think it should be that way, but unfortunately in this country it is.

Well, let’s just traipse quickly through your scholastic career. You got a bachelor’s degree at MIT and a PhD at Cornell?

I got two bachelors! One of them in science and the other in the humanities, music and foreign languages in translation, so I hadn’t quite chosen to focus yet.

Every time I hear about Cornell, I think of Carl Sagan. Did your paths ever cross?

I walked past his house every day on my way to school the first year I was there, but don’t remember that I ever actually met him.

You’ve had a multidisciplinary academic and professional career, which has served you quite well and you got into a position where that was very helpful and important.

For planetary protection, and you’ve probably seen that I say this, the most helpful piece of my education was the bachelor’s degree in language translation.

When I saw the humanities degree I wondered what part, or what type of humanities would correlate with a science career? And then you mentioned it was communications and languages, and that made sense to me.

Also music. I have a minor in music, but the degree is in language translation. MIT was not accredited to give Bachelor of Arts, so I have a BS in humanities, which is a bit entertaining.

Plant science, the humanities, music, languages. Each one of those could be a singular pursuit for me but you managed to pursue all of them. When did you know that you wanted to pursue this career? One of the things I read about you was that when you were working on muscle dynamics as a postdoc you said you preferred working on plants because “plants don’t scream”! I found that humorous.

Yeah, plants don’t get upset when you cut pieces off them. It’s called pruning, and they like it! (laughs)

I thought that was an interesting and perceptive comment. So why don’t we go ahead and talk about your career. The most impressive part, it seems to me as a non-science person, were your years as the Planetary Protection Officer for the agency and in connection with that, I read a note saying that your tenure spanned three U.S. presidents, which made me wonder if that was a position requiring presidential or congressional approval, or was it a NASA thing?

No, it’s just part of the Senior Service. It was Senior Technical and then transitioned to a Senior Leader position. I was never a Senior Executive because I didn’t manage anybody. It was a senior service rather than general service position.

Would you like to say something about your path to Ames and from there to your eminence, if you will, at headquarters?

I wouldn’t call it eminence. Unfortunately, the role was not as eminent as it should have been. Even when I was in the position it was gradually degrading in eminence, shall we say, to the point that I don’t think it currently has any effect. Planetary protection is not implemented effectively anymore. NASA decided not to do planetary protection to a meaningful degree, so we’re not going to do what should be done, and people have to just hope there is nothing nasty out there that we might bring here. Which is quite problematic.

I did notice that there was what you might call a change in organizational support, or in management direction, for the work you were doing. I read your arguments and since I’m a resident of Earth, I think it’s important work. You said it’s important to know, when an astronaut comes back with the sniffles, what caused them, and I thought “Yes! Yes! Yes!”

We should have learned that in the last three years of COVID, right? And the people who lived in the Americas before 1492 learned it in spades, really.

An apt comparison!

I mean, as archaeologists have started uncovering what the population of this continent really was prior to the European expansion, it’s mind boggling. And because history is one of my hobbies, sidebar hobbies, all the way back to my childhood with my dad again, learning from those lessons is important or we’re just going to repeat them, which is what we seem to be doing right now.

As a kid growing up, I was always doing science. I did science and I did music and languages, which includes being interested in understanding what people meant rather than just what they were saying. And then I took several courses at Harvard because MIT did not do plant biology. MIT started out with molecular biology and went downwards. In my senior research lab, somebody asked. “Neurospora crassa: is that a plant or an animal”, as if there were only two options. None of the students had learned any taxonomy. We hadn’t learned how organisms on Earth are related to each other.

The fact that there were more than the four model organisms used in the lab was something that most of the students didn’t have any awareness of, even though MIT did have a collaboration with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. I went down to WHOI for a very short period, but it didn’t occur to me that I could have done that as my scientific undergraduate career. I wish MIT had made more information available, at least at the time that I was there in the mid ‘80s, about what their other study options were, more than the straight core trajectory.

So, I took some classes at Harvard in botany and went to Cornell in plant science. And I also got into UC Davis, so I could have come out to California a lot earlier, but Cornell gave me a better fellowship. And I like snow! So that’s one of the reasons why I’m still back on the East Coast and not in California now.

At Cornell I again had two different major advisors. The lab I was in was in the genetics department, but I was also doing a lot of microscopy, which was in the plant science department. And although the major focus of the lab in the genetics department was on petunias, we discovered RNA editing. My bench mate sitting next to me discovered the first RNA editing in any organism in the early ‘90’s and she got so frustrated with having all these ‘errors’ in her sequencing data that she went on to get an MD and she’s now a doctor.

Plants never get the respect, at least the funding respect, that human biology does, but as the climate gets warmer plants are going to become more and more important, since we eat them. Parenthetically, this again involves my interest in how different parts of the world are related — this decade, I think, is really where it’s going to become obvious to many more people than want to realize it how a warming world will affect them.

Because plants didn’t get much respect, for my postdoc I decided to go to a research lab that was studying a function that was well-understood in animals, with the intention to take that research away with me to start my own lab studying the same thing in plants. It was something I discussed with my postdoctoral advisor before I agreed to come to her lab, that I would be able to take my research project away from the lab with me and she wouldn’t try to hold onto it, so I wouldn’t have to create an entirely new set of research topics for an anticipated future academic research career.

My postdoc was on proteins that regulate actin filaments in the cytoskeleton. I studied a protein that was different but related to the other proteins they were studying in the lab, but it turned out that the function we all were studying was an animal specific function, a muscle specific function. The Salk Institute down the street was where they discovered the proteins that carry out the equivalent function in plants. Those proteins also exist in animals, they just weren’t the proteins I was was studying, which meant I couldn’t take my postdoc research and apply it to plants for my career.

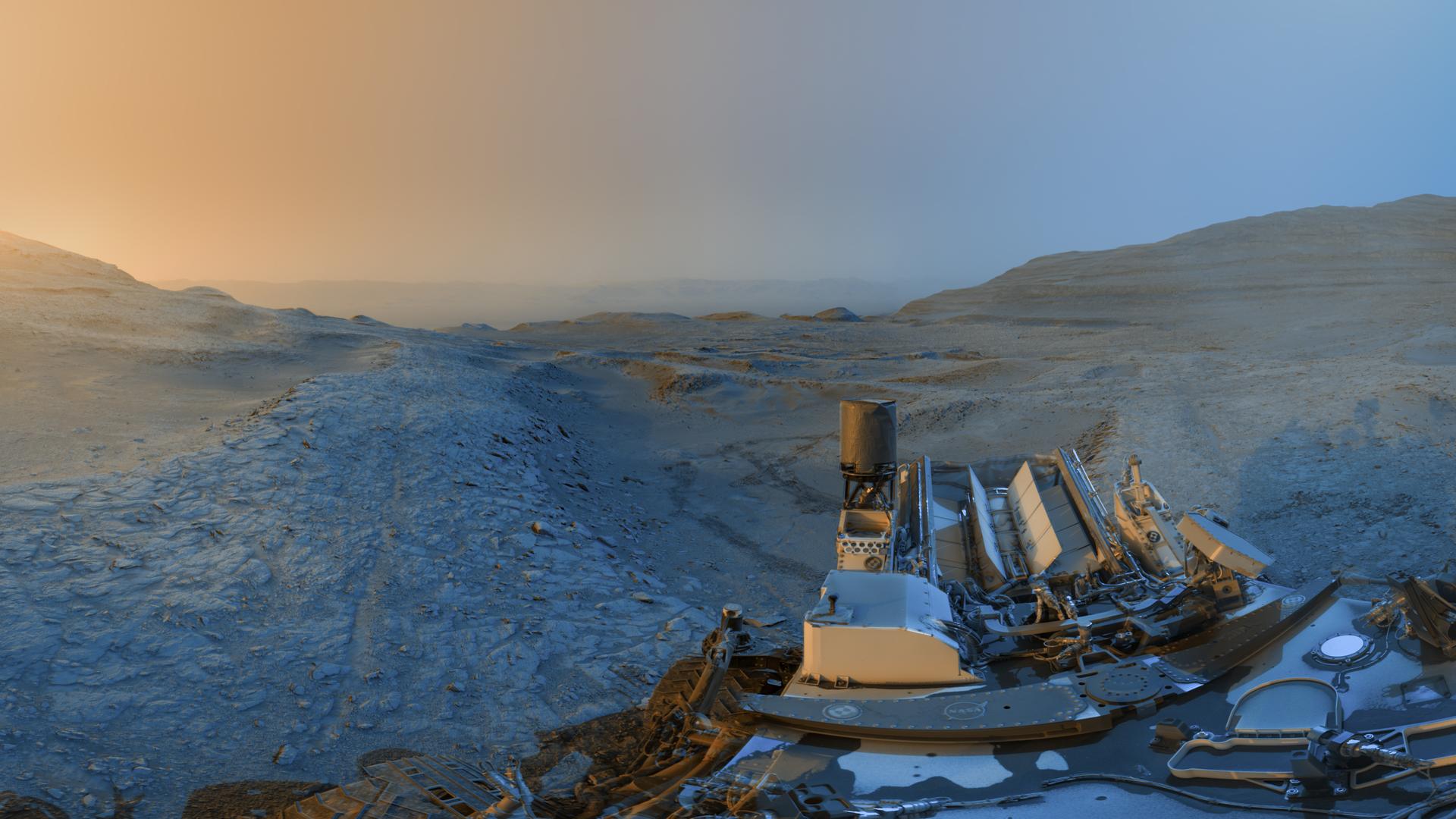

This was around the same time that the Pathfinder rover was landing on Mars, and I was following that on the web. In trying to figure out what I should do next, it was the muscle specificity and the necessity for having this function in muscles that reminded me that astronauts get muscle atrophy — so, since my protein could be involved in muscle atrophy, maybe I should send a note to somebody at NASA. I looked on the Pathfinder website and sent a note to Vernon Jones, whose name was in the contact list at the bottom of the web page, and he put me in touch with Emily Holton at Ames. And that, several months later, is how I eventually got to hear about the job that I applied for at Ames. I was one of several biologists coming in at the same time.

I knew Emily and read that she chose you over 50 other candidates being considered for that selection. She mentioned that it was because your background was unique, it touched so many other things that it was an easy choice for her, and that’s certainly to your credit.

Well, thank you. She never told me that, so thank you.

You’ve talked some about your philosophy as far as planetary protection is concerned, but it’s been now about, what, eight years or so since then. What have you been doing lately? Is it something of a continuation of that?

I’ve been going back to basic research. I’m back in the lab as a visiting scientist at the Carnegie Institution with Andrew Steele, and to some extent following up on both lines of my work at Ames. It is related to the questions that underpin planetary protection, because those questions have to do with: Is there extraterrestrial life? What happens to life on Earth when it goes into extreme environments? And how do you tell, how do you know, that what you think you see is really what you’re observing? Before becoming Planetary Protection Officer, at Ames I was doing space flight work with C. elegans (a free-living transparent nematode) both on the space station and on the shuttle, and of course, Columbia was one of those experiments.

I was also doing field work in the Atacama Desert, trying to understand what organisms lived there and how they survive.

In the Atacama organisms are very cryptobiotic, and it’s not obvious, when you stand in the desert, that there are any organisms present at all. That locale has commonly been used, I think during the Apollo program, as a mock environment for practicing maneuvers on Mars or the moon because it looks very barren, but in fact there’s quite a bit of life there, multiple trophic levels of ecosystems, just that they don’t get enough water to grow very often and they’re not very big.

What Andrew Steele and I are doing now at the Carnegie Institution is work on meteorites and early Earth materials trying to detect organic compounds and signs of life and distinguish indigenous compounds from Earth contamination. He’s got samples in the lab of different Mars meteorites that have landed on Earth and been collected. He had Apollo samples, which nobody realized were Apollo samples because they were inherited from somebody else, until Steele recognized the labels and sent them back to Astromaterials Curation, and he’s getting samples from the asteroids Bennu (NASA Osiris Rex sample return mission) and Ryugu (JAXA Hayabusa2 mission).

Planetary materials that are returned to Earth are a very good system for trying to detect organic compounds and differentiating between contamination from Earth and actual indigenous material. The Genesis mission, you may know, had a little bit of an accident and the return capsule broke open on impact — and figuring out what to do if there’s an off-nominal landing and something gets contaminated on landing is much better to do with known-to-be-nonbiological samples than it would be with potentially biological samples. We’re looking at a lot of those lessons learned from previous sample return missions and then using what Steele is doing, the people doing the lab work, the measurements, and establishing how to make measurements with this very high sensitivity in the context of high background to be able to identify potential biological contaminants or naturally produced abiotic material.

My role is working on developing a better statistical framework to understand, when you have these kinds of measurements, how do you combine them, making sure that you don’t have overlap, that you’re not misunderstanding the degree of independence of the different measurements? And then also, given that you have these measurements and they’re telling you a certain amount of information, what measurement should you do next to increase your statistical confidence? To do this, I’m using a framework of Bayesian statistics.

There are software packages that help to organize Bayesian statistical analysis, and other users are developing similar sorts of analytical approaches for doing things like analyzing hospital patient data: if somebody shows up in the ER with a set of symptoms, how do you figure out what is their most likely disease? What are the backup potential possible diseases and what measurements should you make to differentiate between those possibilities? I came up with the question without knowing about these medical-based systems, but now that I’ve discovered there are these tools out there, I’m definitely going to use them.

When you mentioned Atacama and then also sample returns, I thought of Chris McKay for one and Scott Sanford for the other and assumed that you have had some association with their work?

Yeah. Every time I’ve been to the Atacama it’s been on one of Chris’s missions, so Chris is definitely a long-term collaborator, as well as Carol Stoker and Natalie Cabrol. I also worked with people in the SmallSat group, and with some of the other researchers in my branch.

What do you like best and least about your job? You work for NASA, a government agency, and you’re pursuing science, so there’s probably something you enjoy doing and something you enjoy less, that’s the crux of the question.

The reason I chose to go to a government lab instead of an academic lab was because I had a lot of experience as a TA (teaching assistant) at Cornell, teaching students with different levels of investment in what they were doing. And while I love to teach people who want to learn, it drives me crazy to try to shove information into people’s heads who don’t want it, so that was why I chose to go to a pure research government job, rather than academics.

You have very well considered and practical reasons for the things that you choose to do, and I admire that.

Thanks! When I make a decision, I try to think about the different factors that go into it. Maybe that’s just a general characteristic of my personality. I usually understand why I’m trying to do stuff. People tell me that I’m very self-aware, but it’s like, how would I know what to do if I weren’t? Being in a government lab means I don’t have to teach students who don’t want to learn. It also means that it’s difficult to get students in general, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s nice to be at Carnegie because there are a lot of postdocs and other opportunities for people to come in, young people, young scientists, to come in and learn with us, which is something I really appreciate.

What I like best is just figuring out interesting questions and then finding out the answers. The actual research process is something in science that I really enjoy. As you said, I think about questions a lot, and about how to answer them. It is consistent with my general behavior. Something I don’t like, in contrast, is the politics. Most of planetary protection at headquarters was dealing with politics, and I despise it, and most of the things I do now that involve politics, I still despise. Fortunately, I encounter many fewer of them now, so I don’t have to do it as much, but when I do have to deal with politics, I hate it.

As far as a high watermark or significant research finding in your career, is there something that stands out?

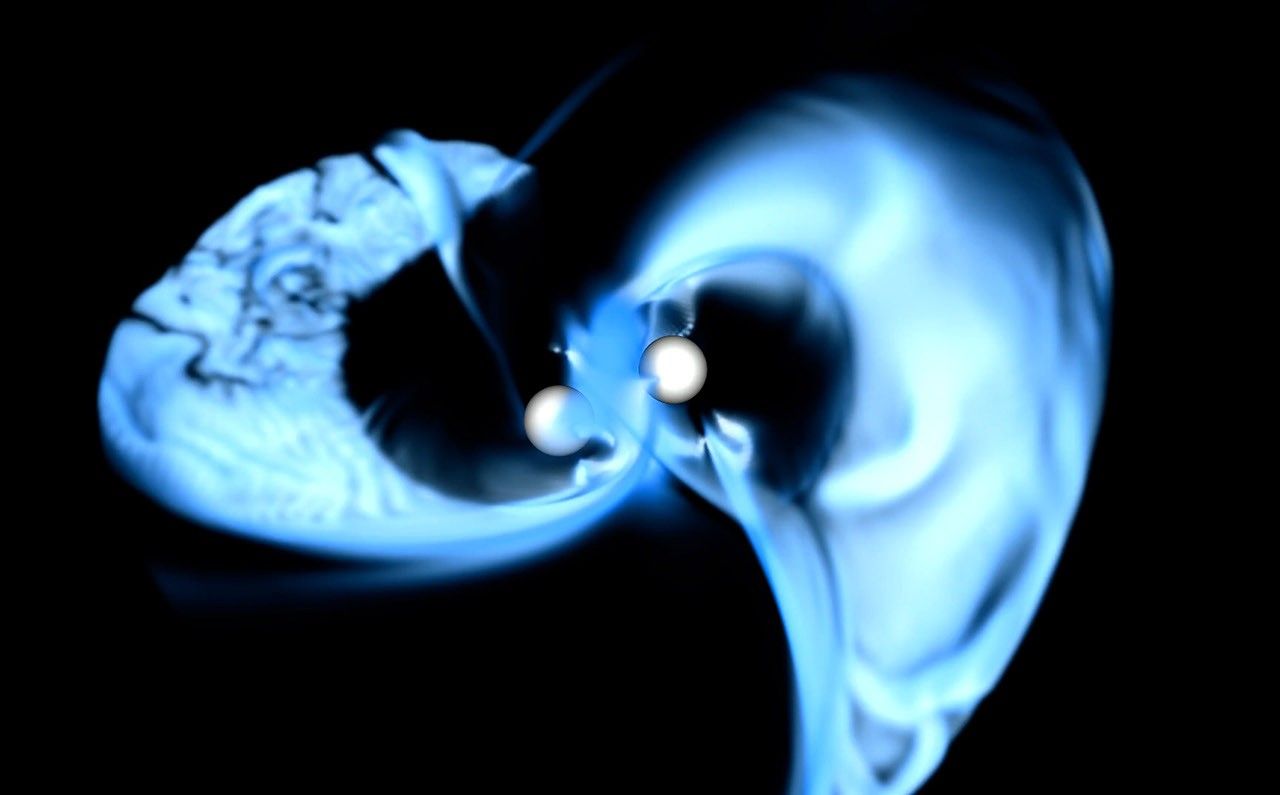

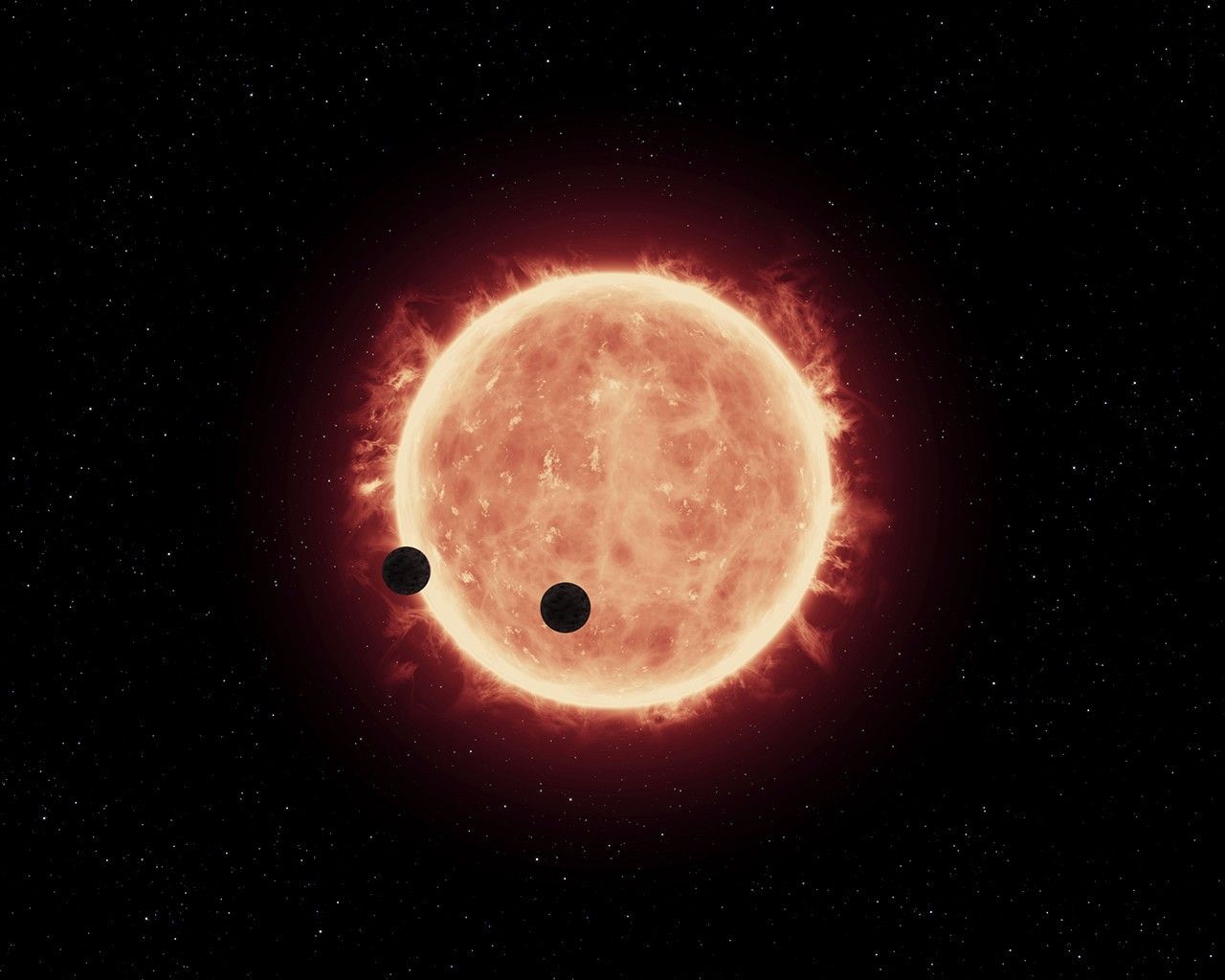

My experiment on Columbia inadvertently demonstrated that animals can survive a meteorite style planetary entry event. That proves one of the major steps necessary for the transport of life from one planet to another by meteorites is survivable. Surviving the ejection event hasn’t been demonstrated, but models suggest that, with big impacts, some of the ejected material doesn’t get badly shocked. So as long as organisms can survive the trip from one object to the other, a transfer is possible — which basically is a demonstrated foundation for why planetary protection should be considered.

It does support your point.

And of course, people argue that, well, if they can get here naturally that means that they’re not harmful. But we don’t know that. All we know is what we can observe now about things that happened in the past, so if Mars organisms got here in the past and then caused a lot of problems, we wouldn’t have any idea. And if we bring them here really quickly, it’s probably going to be worse. If Mars organisms are related to Earth organisms, that means they can exchange genes — and how many harmful Earth microbes are there?

That is sobering to contemplate. You’ve worked as a scientist for NASA in some very important positions. But if you hadn’t, have you ever thought of what your dream job might be?

My dream job currently is to go plant trees on the 40-acre farm I just bought in the countryside. It’s right next to a little eco-village where friends of mine live. The changes in climate are just … well, I think 2023 was the tipping point. We are shifting to a hotter climate, it’s obvious. Current global sea surface temperatures are something like five standard deviations above the 1980 to 2010 mean, which is already a good half a degree C above the pre-industrial mean, and since March of 2023 we’ve been at record high temperatures, in some cases, many cases, two standard deviations above the previous record high temperature.

I don’t have kids, but I have nieces and nephews, and this really bothers me. I don’t have kids because of climate change. In the ‘70’s I decided that adding more humans to the planet was not a good idea. That is my fundamental motivation for not having kids. My interest now is to live in the little community that I’ve decided to retire to, and create a scenario where, if there is major societal upheaval, which I anticipate within the next several decades, they’ll be better off than if I hadn’t been there.

Well, as I said, your decisions are always backed by thoughtful analysis and rational thinking.

But scary analysis, yeah.

As scary as it might be, it’s the right way to make decisions. But what about other countries that aren’t cooperating?

I guess other people not making decisions similarly may be one of the things that I’ve had as a challenge in my career — not understanding that other people don’t think about choices the way I do.

Well, for a variety of reasons, the number of people who are adding children to the world, at least in the U.S., has been going down, probably for reasons not related to climate. Regardless, it is trending in the direction that you foresee.

I would far rather see a planned reduction than an unplanned reduction, and I’m really concerned, with politics in the last year or so, that it’s going to become much more unplanned in the near future, or much more rapidly reducing. I guess this is the worst part of that potential future, yeah.

I don’t know if you’ve had postdocs of your own, but what advice would you give to a student who would like to have the kind of career that you’ve been having? What are some things that they might consider doing? Like taking multidisciplinary classes and things?

I have had a couple of postdocs, and I would tell them to figure out the things that they’re interested in and then pursue them. My career trajectory was entirely unplanned. I had no intention of ever going to NASA headquarters. The only reason I stayed for as long as I did was because I didn’t think anyone else would be doing the job the way it needed to be done. The job wasn’t about me; it was about protecting everyone.

At the same time, being interested in many things; it’s a lot healthier not to care about your own status in the research. It’s not about the person doing the research. Research is about finding out the results. And people who start falsifying data or start thinking that they need to have this outcome because it’s going to make them look better or avoid that outcome because it’s going to make them look worse, they’re not scientists. That’s not science. That’s personal ego. Find the things you’re interested in and just pursue them and don’t worry about what other people are going think about you. Because if you’re doing good work, that doesn’t matter.

Those are great comments and that would be excellent advice for anyone. Having conducted a number of these interviews, I have found that those who, if they did plan out what they wanted to do in their career, it never worked out that way because of all the billiard balls that get knocked this way and that. Some things are just not predictable. Just be prepared for whatever opportunities come up and they’ll wind up in a very satisfying place, a good place, that they wouldn’t trade for what they originally thought they wanted.

Generally, I agree — but, in counter to that, I was a graduate student for six and a half years and then I stayed as a technician to finish up some of the work for another half year. So, I was effectively doing graduate work for almost seven years, and when I was cleaning out my desk to leave, I came across the little research plan that I had to write as a first-year graduate student going into my orals to confirm my place. And everything that I had written down I had at least tried to do. I was amazed. I had totally forgotten about it. But I had written things like doing sequencing, trying to do protein model construction. Some of it was before these kinds of things even existed — I had to go over to the Cornell Theory Center and get them to help me do three-dimensional image reconstruction using the supercomputer, because there wasn’t enough computational power to do it without that. But doing three-dimensional imaging was one of the things I had written down five years before.

Your perspective is interesting and thanks for sharing it. On the personal side, broadening out a little bit, you mentioned that you don’t have kids. Does your family include a spouse or pets?

I have two cats. I have focused so much on work that the whole relationship thing didn’t happen, but cats are relatively tolerant of people working long hours. Currently I have a cat that I’ve only had for a couple of months, who doesn’t like it when I leave the house in the morning. He gets very upset. But I always try to have at least two cats, I had two from the time they were kittens until they died at almost twenty.

After that I was fostering cats for a while, including one that had been badly abused and had PTSD. She needed a companion cat, but the foster place didn’t have an appropriate companion cat for her so I gave her back when I adopted two others, just before the pandemic. These were a brother and sister who had been dumped — they were a little bit timid, but they had obviously been used to humans. A few months later I got a call from the shelter, saying that the one I had been fostering was going to be put down if I didn’t take her back, so I adopted her too. She must have been overdosed on sedatives as she now had hypoxic brain injury as well as PTSD — she just hides under the bed all the time, terrified of everything.

During the pandemic the brother got kidney disease, and the sister got lung cancer, so they both died. I’ve still got the PTSD cat, who’s ten, and the newest one who is four, and they’re trying to get along. The young one is enormous and wants to play, while the older one is rather small and skinny and very timid and hyper-reactive, but they are getting used to each other, slowly. I keep hoping that when I’m not in the house, at least, maybe they’re more friendly to each other. I’m not sure if this happens. (laughs)

That’s what my daughter’s dealing with right now. She’s got two cats. They’re ages are also different, their temperaments are very different, and their behaviors as well. We’ve had cats and we’ve enjoyed them. but when you need to go somewhere, all that you have to do to make sure they’re taken care of was just more inconvenience than we wanted. How about your hobbies, interests, and talents? Do you still play the violin?

I do. I’ve been taking lessons and improving my technique, so I’m a lot better player than I was when I was younger. I play for a small regional opera company where I donate my time — they do pay a little but it’s easier to give the check back to them. I’ve played in several orchestras, and also a lot of chamber music. One of the nice things about being in D.C. is that there are a lot of opportunities to play. I also blow glass and do pottery, so one of the reasons why I’m moving to the country is to be close enough to a glassblowing studio that I can go and blow glass there.

For artistic purposes? Glass blowing to make art objects?

Yes, I blow typical soda-lime glass. It’s not borosilicate for lab glass. This is traditional glass, and I’m interested enough that if I were to do a second degree, I would study the history of glass and the transition, the trajectory, of technological methods to make glass, which started around the Mediterranean near Syria just around the birth of Christ and was transmitted all throughout the Roman Empire. But after the fall of the Roman Empire, the pathways that the technology followed, moving eastward into India versus northwestward into Europe were different. Of course, the Venetian glassblowers came across the Mediterranean from Byzantium, but there was also a trajectory around the east side of the Ural Mountains up into Scandinavia and back down again.

You can tell that these things happened by the glass remnants, and also by the remaining educational transmission of techniques from teacher to student, which is, like biology, one of these things that you can’t record properly in writing. In biology, you have all the cellular architecture and structural relationships between cellular machinery and membranes that have been transmitted from parent cell to child cell since the beginning of life. The architecture and structural relationships are not information that’s carried in the DNA — it’s not possible to build a cell using only information in the DNA. So, I guess how information is transmitted over time is another sort of theme in my set of interests. Some technical things can’t be written down. Sometimes you can’t describe them accurately enough in words — they have to be demonstrated.

Do you have any interest in sports? You mentioned you liked snow back at Cornell. Do you ski?

I don’t. The sports I do are mostly martial arts, though I also sail, ride horses, and go hiking. I have done fencing, and archery and after getting to DC I studied German longsword. I’ve done various kinds of historical martial arts, usually western historical martial arts. I make armor, that’s been part of what I do in the Society for Creative Anachronism, and I used to go out and shoot my friends in battles. You don’t want to hurt your friends; you just want to kill them! (laughs)

That is a bit unsettling, but very interesting! These kinds of things come out when we ask questions like that. It’s the kind of thing that prompts people to say, “I didn’t know he or she was interested in that.”

I usually don’t talk about it and the only time it’s been a problem was at Ames when I was driving in, planning on leaving straight from work to go to a weekend camping event and I had left my throwing axes in the front seat of the car. The guards at the gate didn’t much like that! (laughs) I just said “Oops, I guess I better turn around and take them home!” That was a little bit embarrassing.

But it is interesting. How about reading for pleasure? What genre or kinds of books do you like to read when you’re not reading science?

I don’t read a lot of science books. I read articles but books tend to be somewhat outdated. Popular Science stuff is interesting to me from a translation standpoint, although it’s not something I choose to read. I do read a lot of science fiction, like many technical people. I also read a lot of historical fiction and primary sources, things that were written at the time period I’m interested in studying or am interested in understanding better. Sometimes there’s not a lot of information out there, and you have to keep in your mind an awareness that the words then might not mean the same things that they do now. It opens up a lot of additional possibilities for things that people make assumptions about when they read the texts. I might assume that “x” meant the same thing then that it does now, but that can be totally wrong. Take the word “battery” for example — the word existed in 1600, but what did “battery” mean then? It’s not what most people mean when they say it now. That kind of awareness of how language changes and how that changes the context of the way society works is fascinating.

I think you find everything fascinating. I can feel your passion for the things you’ve talked about, even if they aren’t the focus of your career. That’s a frame of mind and very laudable in my opinion. Let me ask this: what accomplishment are you most proud of that’s not related to your science?

Well, if the trees get planted properly, I would say living on my forty acres. My intention is to design and plant a food forest that will persist, hopefully, for several hundred years into the future, modeled after the kinds of food production systems that were used by North American indigenous people before the Europeans got here. This was up until very recently not recognized as a human-designed food production system. Even now, archaeologists and anthropologists and ecologists are only starting to realize how much the North American forests had been tailored by the people living there. The reason American chestnuts taste so much better than European chestnuts is because the people living here, if they found a chestnut tree that didn’t taste good, they killed it. It was a deliberate selection process for a lot of the North American, or at least eastern, northeastern, New England and Great Lakes area forests. They were selected for thousands of years by the people living there, and the Europeans couldn’t see it because it’s not a European style of agriculture.

That is a fascinating fact. And you’re probably full of them! I always learn things when I talk with people.

Well, so that’s what I’m trying to recreate. And if I can recreate that, I will be proud of it.

You may have already touched on the answer to this, but what do you do for fun?

Oh, blow glass, ceramics, music, playing with my cats. Plus, I read lots of things.

Who or what inspires you?

Well, as for people, my dad mostly. He had a very eclectic set of interests. Books are one of the things we haven’t mentioned yet, but I live in a library. Basically, my walls are twelve inches thick because they’re all covered in books and the house I grew up in was the same way. So yes, I guess it’s my dad, because he had a similar mindset that if there’s something out there and you want to learn it, go learn it. Don’t skim the surface. If you’re going to spend the time, then put in the effort to do it properly.

When my kids would ask me a question at the dinner table, they would preface it with “Now don’t go get the encyclopedia. If you don’t know the answer, that’s fine.” They would ask me a question and I would want to give them an authoritative answer from the encyclopedia. And I wanted them to know how to find the answers for themselves. Of course this was before Google!

But understanding what you do know and what you don’t know is part of that.

That’s a good point.

If I don’t know the information, I’ll say I don’t know, but I know where to find it.

As we put this together and get it ready to post it on the website, which takes a period of time, we’d like to include some images that relate to the conversation we’ve had and I generally ask if you have a favorite image that we might find on the wall of your office or lab, something that you find particularly interesting, and it can be about your work or not.

One of the things I did as an undergraduate was paint on the wall of my room. It was a small living room and I painted an image from Voyager of the entire planet Saturn, with many of Saturn’s moons. So, if you want an image that inspired me, I painted it on the wall of my dorm, 12ft long x 8 feet tall, when I was in college!

Here is the original image, but I don’t think I have one of the painting.

It’s beautiful! And feel free to send anything else that relates to you, your work, your interests, or your cats, anything we’ve talked about just to sprinkle through the post, because it does make it more interesting and readable. You can think about this because it will take some time for me to get this on paper. And then it goes into a queue with a few ahead of it and, so we’re looking at probably six months or more before we post it. Anyway, do you have a favorite quote that you find motivating or inspirational?

Well, the quote that I most often repeat is attributed to Mark Twain when he was a newspaper reporter: “You’ve got to have the facts before you can pervert ’em” (laughs).

I love that because I haven’t heard it before.

That was one of the things I kept pointing out to people in planetary protection who wanted to just ignore the facts. If you want to do something stupid, go ahead and do it, but at least understand what the implications are. Or don’t go ahead and do it, if the outcome could be bad… At a minimum you’ve got to have the facts and then you can decide what to do with them.

I love that, Cassie. This has been fascinating. I’m trying to remember if I have ever met you personally in in my career.

We did. I’m sure we did, but it was at one of those meetings where I was somebody in the audience and you were standing in front of the room. It wasn’t very personal.

There were a few times when I stood up in front of the room. It might have been an NPP (NASA Postdoctoral Program) meeting of some kind. But regardless, I’m delighted that we were able to have this conversation. This is going to be a wonderful addition to our archive of scientist interviews. Is there anything you wish that I had brought up or asked about that I didn’t?

The one thing I was going to suggest was if you’re going to want a picture of me, why don’t you take a screen capture right now, because that way you’ll have one.

OK, that would be great, and then any other pictures of your life or your science work, or if you went to an exotic place or something like that. And when you come back to Ames sometime, it would be nice to meet you in person. Problem is I haven’t been to Ames for almost four years; I’ve been working from home.

I understand. I go into work when I need to be in the lab or if I need to have an in-person meeting, otherwise I work from home.

I like Teams meetings a lot better because you see everybody, you hear everything and it’s comfortable. Thank you so much for your time. Do you have any questions?

Umm, no. Thank you for the invitation, thank you so much.

________________________________________________

Interview conducted by Fred Van Wert on January 30, 2024