The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite

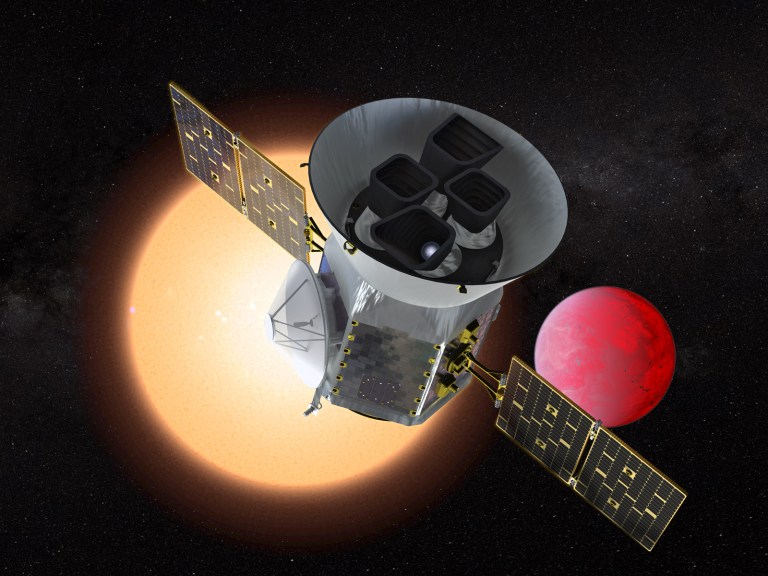

he Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is the next step in the search for planets outside of our solar system, including those that could support life.

Contents

About TESS

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is the next step in the search for planets outside of our solar system, including those that could support life. The mission will find exoplanets that periodically block part of the light from their host stars, events called transits. TESS will survey 200,000 of the brightest stars near the sun to search for transiting exoplanets. TESS launched on April 18, 2018, aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

TESS scientists expect the mission will catalog thousands of planet candidates and vastly increase the current number of known exoplanets. Of these, approximately 300 are expected to be Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized exoplanets, which are worlds no larger than twice the size of Earth. TESS will find the most promising exoplanets orbiting our nearest and brightest stars, giving future researchers a rich set of new targets for more comprehensive follow-up studies.

Mission Approach

TESS will survey the entire sky over the course of two years by breaking it up into 26 different sectors, each 24 degrees by 96 degrees across. The powerful cameras on the spacecraft will stare at each sector for at least 27 days, looking at the brightest stars at a two-minute cadence. From Earth, the moon occupies half a degree, which is less than 1/9,000th the size of the TESS tiles.

The stars TESS will study are 30 to 100 times brighter than those the Kepler mission and K2 follow-up surveyed, which will enable far easier follow-up observations with both ground-based and space-based telescopes. TESS will also cover a sky area 400 times larger than that monitored by Kepler.

In addition to its search for exoplanets, TESS will allow scientists from the wider community to request targets for astrophysics research on approximately 20,000 additional objects during the mission through its Guest Investigator program

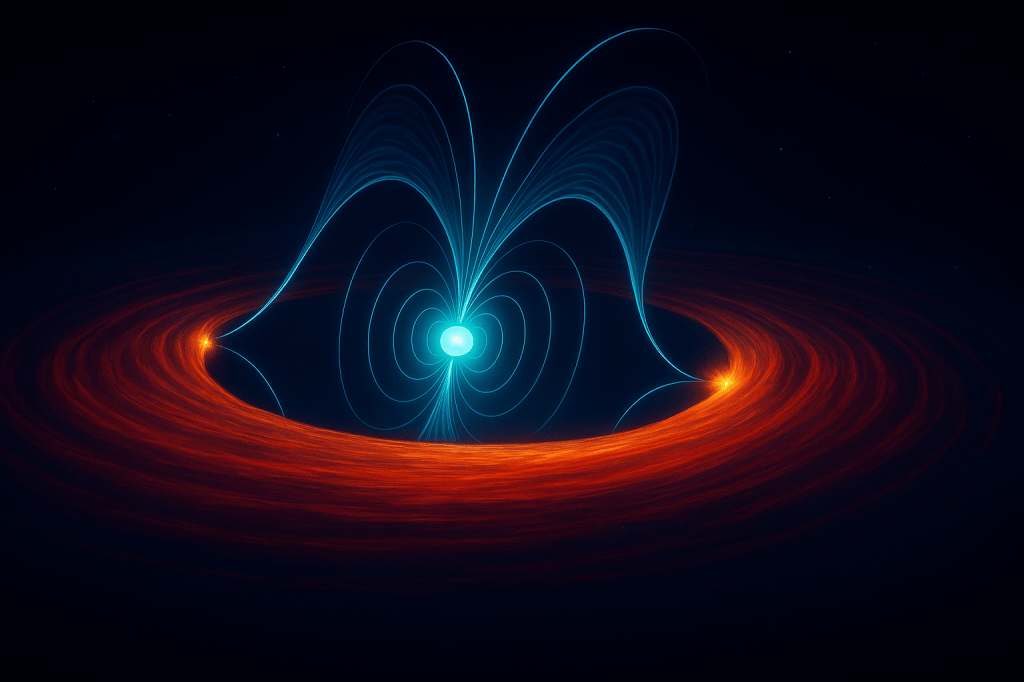

The Transit Method

The transit method of detecting exoplanets looks for dips in the visible light of stars, and requires that planets cross in front of stars along our line of sight to them. Repetitive, periodic dips can reveal a planet or planets orbiting a star. Transit photometry, which looks at how much light an object puts out at any given time, can tell researchers a lot about a planet. Based on how much of a dip in light a planet causes in its star, we can determine that planet’s size. Looking at how long it takes a planet to orbit its star, scientists are able to determine the shape of the planet’s orbit and how long it takes the planet to circle its sun.

TESS will create a catalog of thousands of exoplanet candidates using this transit photometry method. After this list has been compiled, the TESS mission will conduct ground-based follow-up observations to confirm that the exoplanets candidates are true exoplanets and not false positives. These ground-based telescopes will collaborate with other ground-based telescopes to measure the masses of the planets. Using the known planet size, orbit and mass, TESS and ground-based follow-up will be able to determine the planets’ compositions. This will reveal whether the planets are rocky (like Earth), gas giants (like Jupiter) or something even more unusual. Additional follow-up with ground- and space-based missions, including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, will also allow astronomers to study the atmospheres of many of these planets.

TESS team partners include the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, Orbital ATK, NASA’s Ames Research Center, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and the Space Telescope Science Institute.