From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

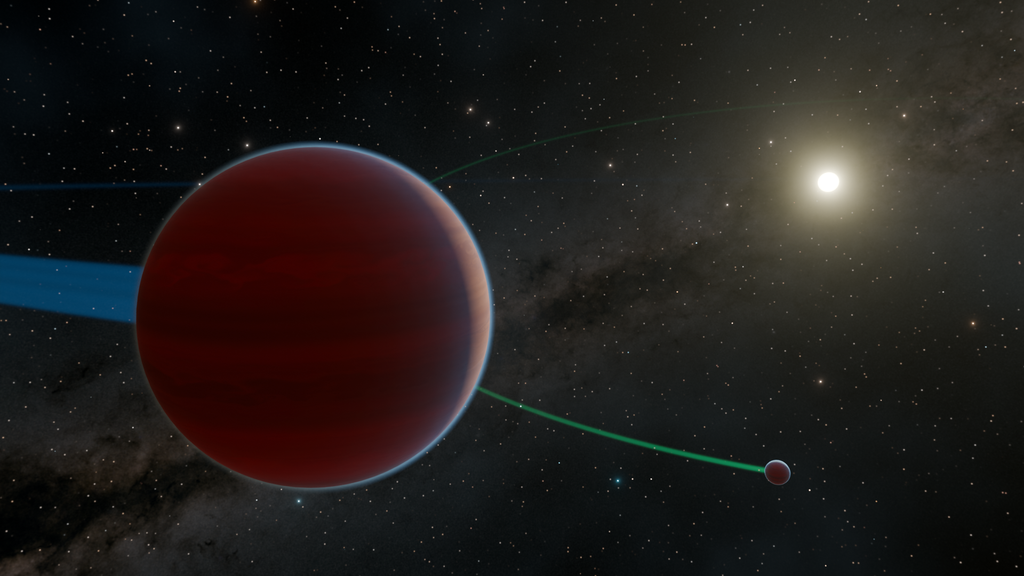

On episode 333, the CHAPEA crew checks in on their ninth month in a Mars simulated habitat, and a Mars architecture expert explains CHAPEA’s role in NASA’s long-term plans to explore the Red Planet. This is the ninth audio log of a monthly series. Recordings were sent from the CHAPEA crew throughout March 2024. The conversation with Michelle Courtney was recorded on April 1, 2024.

Transcript

Host (Gary Jordan): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 333, “Mars Audio Log #9.” I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. We’re back with another audio log from the CHAPEA crew. CHAPEA, or Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog, is a yearlong analog mission in a habitat right here on Earth that’s simulating very closely what it would be like to live on Mars. We’re lucky enough to have monthly check-ins with the crew Commander Kelly Haston, Flight Engineer Ross Brockwell, Medical Officer Nathan Jones, and Science Officer Anca Selariu. To meet the needs of fitting in with this analog and simulating significant communication delays between Earth and Mars that prohibit us from having a live conversation, the crew is recording an audio log based off of the questions that we draft for them.

On this episode, we play the recording of their ninth month in the habitat, which is here at the NASA Johnson Space Center, and was recorded in March 2024. We’re also bringing on a special guest to learn even more about CHAPEA. This month is on a broader topic of Mars architecture. CHAPEA is helping scientists to understand what it’s like from the human health and performance perspective to live on Mars. NASA’s current human exploration initiatives with sustained human exploration of low Earth orbit and the Moon serve as a pathway for getting us to the Red Planet. And NASA has defined this pathway in public documentation. You can look it up now. The URL is nasa.gov/moontomarsarchitecture. We’ve had a few recent episodes that expand on this architecture because there’s a lot to it, but on this episode, we’re bringing on a special guest to help us understand how CHAPEA fits into the mix.

We’re welcoming Michelle Courtney to the podcast who goes by Coco, and she’s the lead for crew support systems integration for the Mars Architecture team, also based here at the Johnson Space Center. Coco helps us to unravel more about Mars mission architecture and how CHAPEA fits in with the story. We’re fortunate this month that we get to hear from all four crew members at the same time. So let’s start our episode with a check-in from all four CHAPEA crew members, and then dive into Mars mission architecture with Michelle Courtney. Enjoy.

[Music]

Kelly Haston: Hi, this is CHAPEA 1, the Mars analog mission out of Johnson Space Center, and we are here doing the recording for Houston We Have a Podcast episode 9. My name is Kelly Haston and I’m the commander.

Nathan Jones: I’m Nate Jones, I’m the medical officer.

Ross Brockwell: I’m Ross Brockwell. I’m the flight engineer.

Anca Selariu: And I’m Anca Selariu, science officer.

Nathan Jones: We usually start off by saying how everything’s going and I would just like to report that everything is still going very well for us all. I couldn’t be happier with the crew that I’m here with, and I just am so thankful for all the subject matter experts at NASA who help us get through this mission. Next question, it says to tell us about some of the highlights of the activities and tasks of the last month.

Kelly Haston: So we’ve had, as usual, a packed month. This month has actually been really awesome, in particular for our EVAs. So the EVA experts have provided us with a real, really robust set of tasks and activities out on the Martian surface. It’s a big challenge to try to complete all of our tasks. So that’s been really awesome. We also managed to hit EVA 100 in the last month as well. So we’re really excited to have done so many EVAs during this mission so far, and we look forward to doing even more.

Nathan Jones: Another big thing I would say that we are all really excited about is the fact that crops are back for us. Love that.

Kelly Haston: Why do you love them?

Nathan Jones: I mean, I really enjoy the smell of the crops, the sound of the water running. The lights from those crops are just a whole lot better color spectrum than the normal lights we have. And the food’s not bad.

Ross Brockwell: I’ll second both of those. I was just thinking while you were talking when you said, “Why do you like the crops?” For example, the other night, I sat down to make a salad. I had all these big plans for all the good things I could use to combine with the fresh greens, and I ended up just sitting and eating the fresh greens with no additions, no dressing, no anything, just eating them cause they were so good. So that’s really great to have those. And second on the EVAs. I mean, they’ve been really, really fun.

Anca Selariu: Same for me. I second everything.

Nathan Jones: I had one other thing I wanted to mention for those out there worried about the poor drone rover situation from our poor decapitated rover. It was repaired eventually. Unfortunately, it did suffer a rollover at one point after that in the last month or so. But it’s still working. I’m happy to report that it’s up and running.

Ross Brockwell: Like a lot of NASA rovers, it’s very resilient, that little guy.

Kelly Haston: We may come back to some highlights as we think about them, but we’re going to move on to the next question, which is to describe a personal quality that you think is invaluable for a CHAPEA mission.

Anca Selariu: I will start by saying, I think self-awareness is first, care for the team above oneself and absolute commitment to the mission. Okay, these are three, but—

[Laughs]

Kelly Haston: I love those ones. I would add resilience is one that I think we have. We’ve had I think, a really good run in this mission. The crew has always been really positive, really happy to be here, but it is a long mission, and we are away from our families and friends and, you know, there are concerns from the outside world that we can’t always help or take or help people with. And so I think that resilience to overcome that and still maintain your experience in here and the things that Anca just spoke of is part of the thing that I think is really important here, too.

Nathan Jones: I think a key trait would be patience. Everything just takes longer. And if you think it’s going to take a while, it takes even longer than that. We’re just now under 21 minutes for the first time in over four months. It takes less than 21 minutes to get a message to mission control and then obviously another 21 minutes to get it back. And we will have spent over six months at greater than 20 minutes, I believe before the mission’s over. So just lots of patience, oodles, those other, I’d like to reiterate what other things you guys mentioned. Those are great too.

Ross Brockwell: A word that came to mind for me was perspective. I think that can be considered a trait, right? But just keeping in mind what’s important. You know, keeping the big picture in mind, knowing when to make a fuss about something and when to let something go. You know, you kind of have to make choices on where to put your energy and you learn how it’s best spent, what to worry about, what not to worry about, what to roll with. So I think maybe flexibility is a part of that too. But perspective and flexibility, I would say are very important.

So what’s one activity or item that as a crew you realize there are no way you could do without it? I would say the hot water heater we use to cook is probably one on that list. One of the main ways we prepare foods. So it’d be pretty tough if we didn’t have that for the rehydratable foods, came to mind. There’s a lot of them.

Nathan Jones: Oh, man. There are so many things that I’ve been just really glad to have here with us. You know, I’m just so thankful, and they’re not here with me, but I get their messages in my inbox, and I am so thankful for my supportive family and friends that arrive to me here digitally most days. And could not do it without them.

Kelly Haston: I would second that. And I even get messages from some of Nate’s family, which is awesome. I would say some of the things that I think are really important for us emotionally are the ability to have a lot of books and things to read. And also, and it sounds a little funny to say this, but the tremendous number of shows and movies that we’re able to bring in here, because the crew has actually done a lot of watching together, and it’s one of the activities we do on top of playing games or, you know, doing other puzzles such as and so forth together. But being able to actually come together and have shows that we sort of treat as our special treats at the end of the day together, that’s actually been really, really special. And part of our sort of pattern and our daily habits. And I think those have been really important.

Anca Selariu: For me, it’s living things other than humans and microorganisms, of course. I would not go to Mars without having the ability to take other Earthlings with me. And I would personally love to have representatives of all kingdoms of life and study how they adapt to extraterrestrial conditions.

What is one activity or item your item you’re kicking yourself for forgetting to bring? Well, I cannot really think of anything. I think pretty much we have everything that we need here, but there are things that I want, but the things that I would have liked are not exactly authorized here, such as trees or cats. But I have pictures of trees and my friend sent me pictures of cats and bonus science articles. So I feel all set.

Nathan Jones: Maybe a pet mouse might be in the cards someday. You know, you be a science mouse, but—

[Laughs]

Anca Selariu: I have a stuffed bat if that helps.

Nathan Jones: Said stuffed bat was never alive in the past, I should say that.

Kelly Haston: Yeah, definitely.

Nathan Jones: A stuffed animal to begin.

Anca Selariu: Just a toy.

Kelly Haston: We had some suggestions for things to bring in and I brought in maybe one pair of shoes too many, and I wish instead I had brought my moccasins or a different pair of shoes that made me think of the outdoors and home a little bit more instead of just my trainers.

Nathan Jones: I actually can think of more things that I brought that I was now realize I didn’t need then things that I really, really, really just wish I would’ve brought in with me. I’m sure she’ll listen to this when it comes out. And so I’m just going to take the moment to say, my wife would like me to have brought a barber with me. Hair’s getting a little long and shaggy. But other than that—

Anca Selariu: Let the record show I offered.

[Laughs]

Nathan Jones: We we’re looking into it. So, otherwise, I’d say I’m doing pretty well as far as nothing I absolutely have to have.

Ross Brockwell: I would like the record to show that the haircut situation is part of the science being done.

[Laughs]

Ross Brockwell: So that’s my perspective on that. Similarly to the footwear comment, I would’ve brought an excess pair of sandals. Just a convenience thing.

Nathan Jones: I have one other, just because I throw one of these in every single one of the podcasts so far, you know, “world’s best,” I should have brought, this is my only chance to ever get to use something like this, “World’s Best Dad” mug. I mean, when else could you ever actually, I mean, maybe I am though. You know, you never know. You never know.

Ross Brockwell: You could be the first to say you’re the world’s best dad on two different worlds.

Nathan Jones: Doubt that’s true. But thank you. Something to aspire to at least.

Anca Selariu: And also, aluminum foil.

Nathan Jones: Oh yeah. Aluminum foil. Alright.

Kelly Haston: Alright. So it’s heading into spring and I know that we’re pretty excited for spring. I personally am excited for the time change, even because I haven’t changed my watch. And so now it will be on the right time again instead of me having to do the math each time I look at it. But what would you look forward to on Earth if you were experiencing the spring? What does everyone miss?

Anca Selariu: Well, I can say that I’ve lived in many parts of Earth and spring has looked very differently from one year to the next. And I know it sounds cliche to say this, but I really miss the biosphere wherever it may be. All the colors, all the smells, all the sounds of Earth. I miss wind and water in all forms and sun. And I’ve never in my entire life been so aware of my connection to Earth. The reality of being an Earthling never hit me as much as it did during these past eight and something months. So I guess it’s an experience that if all Earthlings got to live through, they’d have a different perspective of how precious Earth actually is.

Nathan Jones: A few years ago, my family moved into house that had just a lot of tulips and other flowers planted around the property. And so one of the best things about spring is just seeing those Easter lilies pop up and followed by all the other various flowers, all those colors, just pushing up every single season in the spring, I should say. But also just, you know, the sound of like a big downpour of rain on the roof as you’re falling asleep. Or even just sitting and listening to something like that. Just kind of missing that at the moment.

Ross Brockwell: Yeah, a couple things came to mind. I mean, the day in the spring where it’s warm enough to go in the water without a wetsuit, it’s pretty great, cause usually, it’s a sunny day and it’s warm in general, but when the water’s warm enough to go back in without a wetsuit, it’s really, really great. And then the day where the Sun first comes up over the water is also really, really cool. Just the colors and everything, the light sun, you know, marking that summer’s coming and it’s getting warmer. It’s great.

Kelly Haston: For me, spring is a time where my community comes together again after a quiet period. So I do ultra running in my spare time. And even though I live in California, which is lucky, and we actually are able to run fairly comfortably throughout the year, you know, people take a break and there’s not as many races or events that people take part in. So that coming back together of both, the atmosphere, the weather, the things that everyone else just talked about, and then also seeing people that you haven’t seen for several months, and the excitement of knowing that you’re facing a whole new year of challenges or, you know, a season of challenges in racing or whatever your personal goals are in terms of being outdoors with your friends. I love that sense of community that sort of feels invigorated after a break. And you just are reminded of why your community is so special and why those people are like a delight and a richness in your life. And so I think that the spring always makes me think about that in both the environment and also people.

Nathan Jones: What’s coming up in the next month?

Anca Selariu: Boom, boom, boom. Well, I’m really hoping a drone, a rover mission because I can’t wait to see the two little guys help us do science again and explore new parts of Mars and find interesting things that we never expect to find.

Kelly Haston: So we have a ton of special occasions that I’m sure Nate might actually give you some flavor of. But I wanted to also use this opportunity to give a shout out to some of our that are based at Johnson Space Center.

Nathan Jones: Cannot emphasize just how great NASA’s support systems have been for us. And just how they keep us, you know, a part of Earth whenever we’re so isolated. And that has been definitely one of the highlights of the experience. As far as milestones go, we’ve got St. Patrick’s Day coming up. I’m not sure exactly how we’re going to celebrate that. We’ll come up with something creative, I’m sure.

Kelly Haston: We have some green icing.

Nathan Jones: We have something, I’m sure we’ll come up with things. How exactly and when, we’ll see. I think a day that we are all looking forward to is in mission day 278. We will have 100 days left on Mars. And I think it’ll be a reflective time for us, an exciting time for us. And just to really going to start, probably, what I think a lot of us are going to see as the beginning of the end of our mission here.

Ross Brockwell: Yeah. More of the same. I’m looking forward to seeing what they challenge us with. And, you know, those milestones are always something to note. I feel like we know the fifths, there’s probably a fifth coming up too, right? Four fifths coming up maybe. But yeah, those milestones, when we hit them are meaningful. So a lot of things to still look forward to.

Kelly Haston: Any final thoughts?

Nathan Jones: No. Thank you everyone for tuning in and listening to us ramble every month. Maybe me more than the others here, but appreciate just everyone’s interest in our mission and listening to us every month.

Anca Selariu: Group chant.

Nathan Jones: Oh yeah, let’s do it. 1, 2, 3.

All: Don’t die.

Nathan Jones: Well, that was great guys. Good job. Alright.

Host: Alright. That was the CHAPEA crew on their ninth month in the habitat. It is always such a pleasure to hear from the crew, and this is the second time we’ve heard from all of them all at the same time. And I don’t know about you, every time I hear from the crew and just hearing their energy even after nine months, they have such a wonderful and optimistic approach to life that is just contagious. It’s wonderful to hear from them. Congratulations to the crew on a hundred EVAs. Just thinking about that, the record for a U.S. astronaut and the number of EVAs in their entire career is 10. And now we’re talking about on a Mars mission, them, as a crew, conducting a hundred EVAs. It’s just going to break all records whenever we get there. It’s something really to look forward to. At the end there, Nate talked about, you know, thanks for listening to all of our rambling. Again, I don’t know about you, but I am just really enjoying the crew’s journey, not rambling, just hearing their perspective on life and the crew’s perspective on missing Earth and missing the sounds and the smells. I just really look forward to following them through the rest of their journey and can’t wait until they finally egress and get to enjoy Earth once again. And hearing their appreciation of life and of Earth after this entire experience. It’s going to be truly inspirational. Alright, with that, let’s now switch gears and talk with one of the experts that’s refining the architecture of a human mission to Mars.

Michelle Courtney. So happy to have you on Houston We Have a Podcast.

Michelle Courtney: Thanks for having me on. I’m excited to be here.

Host: You go by Coco. That’s a pretty cool name. What’s the story behind that?

Michelle Courtney: Yeah, it’s actually kind of a fun one. So I did the HERA analog back in Campaign 3. This is like 2016 timeframe. We all had assigned roles in the mission and mine was the commander of the mission. There was another crew member who had a very similar name to mine. So to differentiate, my nickname became “Coco,” which was short for “Commander Courtney.”

Host: Very good. And that translates really nicely because you work now in the Mars architecture team with Michelle Rucker.

Michelle Courtney: I sure do. Too many Michelle’s on that team. So we had to come up with a differentiation. And it’s really handy when you walk in with a nickname that you actually like.

Host: Coco’s pretty good.

Michelle Courtney: It is. Because normally when you get a nickname it’s not for a good reason. So this was a good one.

Host: Very good. Well, Coco, tell us a little bit about you. You’re from Melbourne, Australia.

Michelle Courtney: Yeah, I am. I’m an aerospace engineer. I originally came from Melbourne, Australia. I got my degree at RMIT, which is the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. But then I came to work in the U.S. and, specifically, obviously, in the aerospace industry, but went on to develop a strong background in structural design in both commercial aircraft and experimental vehicles. And that was air and space vehicles. Think like NASA’s X-59 Supersonic Low Boom demonstrated that recently got a great unveiling in Palmdale, California. And then I also worked at Virgin Galactic spaceship company out in Mojave on their SpaceShipTwo vehicle. But it was while I was doing my masters in aeronautical engineering at Embry-Riddle, that was about a bit over a decade ago. I took a stronger in interest in human factors and space medicine. And that really put me on the path that I find myself on today. Actually, it was when I was at Virgin Galactic, I applied to and got selected to that HERA mission that gave me my nickname there. So it was a really fun experience. I was a part of an all-female crew. And yeah, again, that’s where I earned that nickname.

Host: Very cool. So, I mean, well, Melbourne, Australia, I wonder if there was something there, cause you seem to hop across the pond and now and just dive right into. It seems like there was some maybe something in Melbourne interested you in spaceflight and aerospace. What made you make the move? That’s a drastic change.

Michelle Courtney: Well, it is a big drastic change. I had always wanted to work for NASA, but it wasn’t so clear to me when I started my career a couple of decades ago that there was a particular path to get there. And as someone who grew up in another country, that wasn’t so obvious. So by sort of falling into various aerospace roles, I eventually made my way here. And I found that the experience that I gained in industry was invaluable to my experience here and the types of contributions I could make.

Host: Was there a mission or just something that inspired you to pursue that? Because that is a dream that you say, you know, to go full-fledged into, right? Was there something that was happening in your life? Maybe it was a movie that you saw?

Michelle Courtney: So I’ll credit my father on this one. I grew up with a steady stream of sci-fi movies and books. So I guess that’s really what inspired me to get into space.

Host: Well, here you are and we’re very lucky to have you we’re talking about something so cool. Mars architecture. I mean, it’s so funny because you think about the Mars mission and how it being far out, but every time, cause this is not the first time I’ve talked to somebody on the team, it just sounds like, my gosh, you guys are so busy. So tell me about the team. What are you guys doing to stay busy and make sure that you’re defining these objectives to help NASA later on?

Michelle Courtney: Absolutely. Well, I’ll start off by talking a little bit about the role that I have and then how that fits into the overall team. I wear a couple of hats. Firstly, I’m part of the Engineering Directorate at Johnson Space Center, but really, I’m talking today in my role as the crew support systems lead in the Mars architecture team. And that’s part of our strategy and architecture office, which is under the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate. And it’s a system engineering type role. There’s a lot of cross directorate and mission directorate integration. We’re working through how agency-level objectives for exploration can be composed into specific functions and use cases and how they can be integrated with all the other aspects of an architecture such as the transportation system and habitation systems and surface systems as well as entry, descent and landing. It’s about identifying gaps in our knowledge and then doing the analysis to fill it in. And the team that we have, the size varies a little bit, but it pulls in folks that are needed for specialized analysis tasks that we perform each year.

I think one of the great strengths of this team, which I really adore, is that we’re from a diverse set of engineering and science related backgrounds. And we have such a variety of roles within our team and we’re spread out across multiple NASA centers such as Johnson Space Center, Marshall and Kennedy Space Flight Centers, and Glenn and Langley Research Centers. It’s a really fun team and I learn something new every day. But my particular role is to ensure crew driven capabilities and needs are captured and integrated into Mars architecture that support crew health and performance and crew operational considerations. And to do that, I work hand in hand with the flight operations directorate and the crew office to ensure their perspective and operational considerations are accounted for. But I also work closely with the human health and performance directorate and Human Research Program that ensures that their expertise and their standards, like NASA Standard 3001 are represented in the Mars architecture development. Those standards are actually fascinating, by the way, if you want to know more about the human body and what it can tolerate from its environment and all the physical and psychological needs that humans have. And there’s a lot. And not to mention all the complexities of trying to integrate humans into the vehicle to work effectively with those systems. I’ll wrap it up by saying again, it’s a really fun role and it scratches an itch that I have as an engineer and scientist to always keep learning and to look for creative ways to make spaceflight achievable and hospitable to humans.

Host: It sounds super fun and I envy it in some ways, but others it just sounds like so overwhelming that I actually don’t envy it. But I don’t know. For someone who has dreamed about doing this for so long, I feel like it’s probably your dream to do something like this.

Michelle Courtney: It is. I think if I could write a note back to myself 20 plus years ago and say, “Hey, in 20 years you’ll be working at NASA and you’ll be working on this team and looking at human spaceflight to Mars,” I don’t think I would’ve believed myself.

[Laughs]

Host: You’re like, “Okay, yeah.”

[Laughs]

Michelle Courtney: Exactly right.

Host: You must be our third or fourth architecture guest. We’ve had so many conferences because I find it just so fascinating. And the fact that we keep building onto this is, I think, even more fascinating. You can tell there’s a lot of thought being put into just how do we get there. And we just did this wonderful series with Michelle Rucker not too long ago. We worked with her to do, and over the course of a year, we did a series on this podcast called “Mars Monthly.” And every episode would be another aspect to a human mission to and from Mars. It was a wonderful series. So I’m sure though things have changed since we last had those conversations because like I said, it’s just an ever-evolving thing. You have a lot of great minds on this. If you don’t mind just taking us back to that series, what we talked about and maybe a couple of differences that you and your team are already working on.

Michelle Courtney: Yeah. So if I recall the series kind of kicked off with it “Preparing for Mars,” which was an overview kind of Mars 101. Michelle Rucker introduced that, and I think the following parts of that podcast series that, that monthly podcast delved a little bit more deeply into some of those topics. So things like the “Rendezvous for Mars” ones talked about the complications of orbital mechanics and what we need to consider for propulsion and duration of spaceflight and trajectory. And more and more recently, our team has been contributing to analyzing the trade space options. So we have even more data available when we’re ready to start making some decisions about such things. I think you also looked at some deep space transport options and what kind of elements you need to get to Mars, propulsion systems, habitation systems, and the type of trajectories to get there for a long duration transit.

And really, there are a lot of similarities there to the Artemis Gateway vehicle under development. So there’s continuous analysis going on into how Gateway’s vehicle challenges could also help resolve similar for a Mars transit vehicle. Let’s see, what else did you talk about? You talked about packing for Mars and logistics is an interesting one, and that’s a topic I definitely want to hit a little bit later when we’re talking about CHAPEA. But looking at logistics, the need to bring everything with you. Let’s see, we’ll talk about that a little bit more I think later on, because that is intrinsically linked to CHAPEA. And some of the things that we would get out for the architecture, one of my personal favorite topics, is the “Eat Like a Martian” podcast. If folks want to go back and listen to that one, I really enjoy doing the sensory testing at JSC Food Labs. We get to taste the food that the crew members get to eat. We get to rate it on its taste and its appearance and its texture and its aroma. It’s a lot more fun than going to your local big box store and trying those samples on a weekend. I’ll tell you that much.

Host: Yeah. We did that one with Grace Douglas.

Michelle Courtney: Oh, I love it. It’s so much fun. It’s such a critical part to human health and performance. So the shelf life and nutrients balance is key, but also variety, menu fatigue is a real thing. I don’t know if you like me, struggle at the end of the day to go, “What am I going to eat for dinner tonight?” Imagine being a crew member on a long duration mission to do that. And in terms of architecture, also looking at the temperature storage range that you would put these items to increase their shelf life that would have some pretty big architecture implications for us. Think about the volume, mass and power your fridge uses. So that’s one thing that’s being looked at, at the moment.

Also in your series you had the “Live Like a Martian,” and that really talked about the physiological and psychological challenges of being a human on a planet that has reduced gravity, but particularly after a really long period of time for deconditioning. And that one featured our colleagues over in the Human Research Program and what they continue to do to support great work studying the impacts on the International Space Station and other analogs and research projects. From an architecture standpoint, one of the big concerns we have is how soon will crew be ready to perform their mission once they’ve touched down on the surface? Because they’ll need an architecture that’s supportive of that. If they have to hang out in the land for a few days and need some aids to help them, we need to ensure that those capabilities exist for them. If they need to get out to an ascent vehicle in a hurry, we also need to ensure that we have an achievable means to do that.

Another one you talked about, ‘Sticking the Landing,” that looked at entry descent and landing vehicles. We have two really big challenges there. Landing where we want to land and developing a human rated vehicle that can land safely, and that can carry sufficient crew and systems and logistics to keep them going on a surface. That is a challenge with the technology that’s available today. So that aspect is something that we have ongoing research and analysis into at the moment.

Michelle Courtney: “Welcome to Mars” looked at the environment, the weather, the atmosphere. Not much new to add there. It continues to exist, but from an architecture standpoint, it sure poses some challenges. Designing systems that keep crew and vehicle systems at the right temperatures. And with sufficient power, since the risk of dust covering any solar panels could reduce energy production and shut down systems eventually, like we’ve seen on some of our robotic missions in the past.

“Suiting up for Mars,” that one looked at the complexities of spacesuit design for a hostile environment. Remember that suits are basically personal sized habitats for crew to walk around in. When they get to Mars, they’ll have additional challenges like managing planetary protection. That’s not about asteroids hitting a planet that’s about preventing cross-contamination of microbes. And some of the things we’ve been thinking about recently in terms of suit systems are the challenges of picking what pressure and oxygen percentage that the suits will have to have to support mobility. If you have too much pressure, it makes it really hard to move around. Imagine those suits, you know, the ones that people wear that are unicorns or dinosaurs and they try to walk around and it’s super inconvenient to walk in them. So imagine a spacesuit puffed up like that. The mobility is really difficult to do that. Another thing with suits that we have to consider is how long it takes for crew members to adjust to a different oxygen percentage. And that is really important to prevent decompression sickness. And similar to that, we also have to think about the materials that we pick in the spacesuits. Not just in the spacesuits, but in the habitat as well, cause they’re going to need to meet flammability requirements because of that higher oxygen percentage. And since flame doesn’t behave in the same way it does in lower gravity or a no gravity environment. So there’s some of the things that we’ve been looking at more recently in terms of suit systems.

Then I think the most recent one was “Returning the First Martians.” It looked at how a Mars ascent is achieved. And it’s complicated to say the least. Goal is obviously getting crew and surface samples back to Mars orbit. Our team has recently been doing more analysis on different ways to fuel an ascent vehicle, including options where we might use in-situ resource utilization, such as mining ice, to make the fuel. But I’ve got to tell you, it takes a lot of infrastructure and energy and processing time and transfer logistics to get that fuel to an ascent vehicle so that we’d have a way to balance the opportunity with the costs and complexity of doing so. So not so simple. But I think that’s pretty much the series in a whole, it was a fascinating series. I had a lot of fun listening to it.

Host: Oh good. Thank you so much Coco. We had a lot of fun with it and it’s so funny. Thank you for going through such detail too with each of the parts of the series, cause it was not only was it kind of revisiting it, but it was a nice recap of all the different things that we talked about. What I found interesting was some of these problems. There’s such a seemingly maybe small aspect can change your whole architecture thing. The one I locked into was like the shelf stability of food and packing and how that can really change what you need to put into the design of a vehicle that’s going to and from Mars. If you can fix or not fix, if you can address shelf stability. I mean, it changes the mission almost like it’s like those small little things that have such a big impact. This is why we’re thinking about Mars missions is because it’s the details. The devil’s in the details.

Michelle Courtney: It is the analogy that we love to use within our team is that that Mars architecture is like a balloon animal. If you squeeze on one leg to change a particular variable or parameter, you’re really potentially pushing the problem somewhere else. So you have to look at it more holistically. And this is why from an architecture standpoint, we want to look across the mission and across all the different subsystems and sub-architectures to have an understanding of how those little changes can have big ramifications overall.

Host: It’s huge. Also, since we’ve had this series, NASA released this blueprint for Moon to Mars Architecture. And this is what we were talking about in the very beginning when we talked about we’ve had a couple of conversations already with guests who have addressed this blueprint for a what’s called a Moon to Mars Architecture. So last year we had Kathy Kerner on to talk about the architecture document. It’s been some time since we talked with her. What has changed since that conversation?

Michelle Courtney: Well, there was the latest revision of our architecture definition document, and that was released in January this year. And we’ve continued to decompose our Moon to Mars objectives more robustly and also refine our definitions of the lunar segments. We’ve expanded and communicated our architecture more definitively in terms of sub-architectures, such as data systems and management and infrastructure support and in-situ resource utilization systems and autonomous systems and robotics. And we’ve released a new set of white papers on various topics, and they apply to the International Space Station and lunar and Mars topics. But since I’m on team Mars, I’ll highlight the Mars ones. They include Mars mission abort considerations, comms disruption and delay, surface power generation, human health and performance, and round-trip mass challenges. And then finally there’s the key Mars architecture decisions white paper, which lists seven decisions that our team is working on with integrated support across the agency.

Host: Now, the Mars architecture, it’s part of this grander vision of how we evolve from Artemis, right? From those first missions, from the human surface return all the way through a sustainable Mars presence. So I wonder if we can address that for just a second. Let this blueprint. And now when you think about a Mars mission and you talk about some of these subtle changes just to the series, now when you fold in how this evolves from the Moon, how has that impacted some of some of the work in the Mars architecture team?

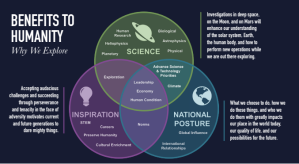

Michelle Courtney: So let’s take a step back and look at why we explore. The NASA vision for exploration centers on the value it provides to humanity. And it could be broadly grouped into three areas. And these we know as our foundational pillars. So there’s science, there’s inspiration, and there’s national posture. And let’s start with the science one. And that’s about understanding how our solar system formed. I mean, that’s an obvious one, but there are also physical and biological sciences and helio and astrophysics as well. And as we learn more, it can be used for advancing technology and providing economic development, which really crosses us over into the national posture piece. Exploration programs provide a significant opportunity to develop our international partnerships and also showcase what the U.S. has to contribute. And finally, there’s inspiration. And I’m personally here talking to you right now because I was, and frankly still am, very inspired by spaceflight and all that’s been accomplished. And all that we can accomplish. Inspiration got me into aerospace engineering and aeronautical science. And it keeps me here. Providing inspiration like this is a fantastic way to encourage folks to get into STEM. But if we want to get a little bit more specific on the Mars side, talking about architecture, so we’re already clear on why we explore, but next we need to work on the “how?” That’s a big question we have. And we need to do it in such a way that we can provide long-term approaches so that we can accomplish exploration continuously and adding to our capabilities so that we can demonstrate we can meet our exploration objectives. This doesn’t mean we’re going to meet all our objectives at once, but it does mean we need to be clear about what they are before we work out approaches to accomplish them.

Host: Because the Mars mission in particular is very, very complex. And we address just how these small things, these small elements of a holistic humans to Mars mission have such great impact on the mission as a whole. So you really have to consider everything so specifically.

Michelle Courtney: Yeah, you do. It’s really a systems engineering approach to identify those technology and capability gaps. And we note them as functions and use cases and we use those two to meet Moon to Mars objectives and those objectives, they’re intentionally kind of generic, kind of high-level cause we need them to stand up to the test of time so that when you read them, they’re really hard to argue with. They’re the obvious things that we want to actually go do. These functions and use cases, they get more granular down from those objectives and then one day they get turned into program requirements and mission concepts of operations. So that’s kind of how you flow down from those objectives to getting into a program that actually gets to go implement them. And that’s really a different approach to how we had been doing it in the past because we can compare and contrast that to what we’ve been calling architecting from the left. Essentially, what we’ve been doing a lot up to this point, and that might be selecting something cause it exists, it’s convenient, we can go grab it and go use it. Or maybe we create a constraint that might artificially limit what objectives we could accomplish. An example of that might be picking a specific date for a mission to happen. And that could limit us to what could be developed, what capabilities could be provided within that timeframe because we haven’t given ourself enough time to look at additional ones. But that’s just not how we want to approach this going forward.

Host: Yeah. That’s so architecting from the right. You start with the objectives. You say what is it that we really want to do? And then figure out, cause a lot of these things, we look at the how the Moon to Mars Architecture evolves. It starts with a human lunar return. And then there’s all of these different phases of establishing and maturing a presence on the lunar surface. And a lot of that is evolved into Mars. So I think how—in terms from the Mars perspective—this would impact, there’s a lot that we’re going to learn in those years on the Moon. Part of the reason that we’re doing it so that you can figure out these challenges, your systems challenges, all these different things. And then, you know, if you define the objectives, some of the functionality, some of the technologies you can use to accomplish those objectives will mature and refine so you can have a good Mars mission design. So it’s like you’re building in evolution to your Mars architecture design.

Michelle Courtney: That’s exactly it. So that’s what the lunar segments are really about. It’s showing a capability increase across the segments. So the human lunar return is about getting boots back on the ground over there. And then the capabilities increase when you look at foundational exploration, that’s maybe adding some more mobility elements there. And then the final lunar segment that they’ve identified is sustained lunar evolution. And that’s really about growing a lunar economy. Adding, again, more of those capabilities for a sustained presence there. So when we look at Mars, Mars is in a little bit of a different situation cause we are really at the kind of human lunar return sort of phase of just defining what we want in that first segment. And we’re still working out what that’s going to look like. We are working on something called a Mars decision roadmap, an architecture roadmap to work out what we do first. And in fact, two of the decision works that we’re progressing through at the moment is looking at what would that first segment look like for Mars? And then how would we build up those capabilities within the missions of that segment. So what’s the space? There’s more to come on that.

Host: That’s right. I guess you’re mirroring a lot of what we’re seeing in the finer parts of a lunar mission. And those three steps from human lunar return to a sustained lunar evolution, the steps that are there on the Moon, this is what you’re doing. You’re trying to build that from a Mars perspective, cause you really are going to have to, you could build an infrastructure on the Moon, but that doesn’t mean you pick it up and place it on Mars. You’re going to learn a lot there to figure out exactly what to do on Mars.

Michelle Courtney: Absolutely. There’s a lot that we are going to learn from the Artemis missions and the capabilities and the technology that we develop for that. And a lot of the technologies, we like to look at them and say, “Hey, is this a Mars forward technology? What about that technology is something that we could use to support humans and exploration on Mars as well?”

Host: I thought about that when you were revisiting the Mars series. You talked about that last of our episodes, the human lunar return, and the word you used is like an infrastructure for supporting, you know, fueling and in-situ resource utilization for that Mars return vehicle. Having the readiness to be able to access that vehicle in a moment’s notice, or at least in a more rapid manner. Some of those things you can find during a lot of the more mature phases of a lunar mission. When you start, “Okay, what does infrastructure on another planet look like? Let’s build it out.” You can learn, take a lot of those lessons and capabilities and put it on Mars.

Michelle Courtney: But when we do that, we also have to accommodate a few additional things. We have to accommodate the fact that it’s further away. We have communication delays. We have a different atmosphere. We have different temperature ranges that exist on the planet as well. So we can learn from the lunar environment, but we also have to tweak it to match what we’ll find when we go to Mars.

Host: That’s very important. Yeah. It’s not copy paste.

Michelle Courtney: It’s definitely not copy paste.

Host: Well, you know, you’re learning a lot now with CHAPEA. This is a big analog mission that’s informing, I’m hoping, and this is part of why we’re having this conversation, is how CHAPEA informs the architecture side. So, let’s start at the beginning. You know, how has your team been working with CHAPEA from an architecture perspective? What angle are you thinking about with the CHAPEA mission?

Michelle Courtney: So the Mars architecture team has worked closely with CHAPEA on a few of the areas that they needed assistance with. One example was communication delays. They were asking, “Well, how long should we set a communication delay within our analogs so that we can make it realistic and we can understand what kind of impact that has to task completion and as a stress it accrue?” So we provided them some information there and they also asked us about some logistics, the consumables that crew would need. And we can talk about that one a little bit more later as well. So we provided some feedback and they’ve also asked us about the type of tasks that we might anticipate crew would perform on the surface of Mars. Because again, they wanted to build a relatively realistic schedule and set of tasks that crew would need to perform out there because it’s really an integrated analog. You want to have things set up as much as possible. So the types of tasks and demands on crew time are pretty similar to what we’d expect on a Mars mission. So they’re the types of things that we’ve been asked for in the past.

I mean, the benefit of doing that is the type of data that we get back is more closely representative and that we could potentially use that as part of our architecture development. So really it’s kind of an integrated loop there of us trying to help set it up to be more realistic and then getting data sets back that can help inform our architecture as we design it.

Host: Very good. You talked about a couple of things. You talked about consumables; you talked about the tasks throughout the day. What are some of the pieces of advice and what are some of the design elements that you passed on from the Mars architecture team to CHAPEA?

Michelle Courtney: So in terms of logistics, we certainly took a look at some of the past usage rates that we would see on the International Space Station. But we had to tailor them more for a mass surface environment. We also had to answer a question about how long do we think crew should be able to take a shower for? Which was an interesting discussion. When we were looking at comms delay with the distance that we have between Mars and the Earth, it can be up to 22 minutes one way. So imagine asking a question of someone, waiting 22 minutes for them to get it respond and another 22 minutes, and getting that answer back, I mean, 44 minutes round-trip on a response is a hard way to communicate. But I would actually say in the current day and age, we do a lot of that already. When we send a text message or an email, we don’t necessarily get that response back. But if you’ve ever waited for the little text message response to comeback, it can be frustrating. So I mean, these are the kind of experiences that are important to apply to these analogs to get a real sense of what impact it has to the crew and their daily operations.

Host: It’s big from a behaviors perspective too. I know some of the behavioral scientists came on this podcast and we’re talking about the benefit of an analog that was very representative of the time delay. We talked about like little things that can impact the entire perspective of a Mars mission. Maybe it sounds like a little thing, but it’s such a huge thing. The delays, it impacts the entire way that you would conduct a mission. It’s so different from what we know.

Michelle Courtney: It absolutely does. And it can change the way the crew time is spent and the crew schedule. Crew time is one of those aspects that I think we’re going to continue to get a lot of data out of analogs such as CHAPEA. It’s a critical commodity during our Mars missions. Just like air and food and water and energy. People don’t think of crew time as a commodity, but it really, really is. So often I’ve heard folks joke that crew are going to be bored on such a long duration mission. But in reality, that’s highly unlikely. I mean, you just look at the ISS daily schedules as an example. There’s plenty to do. In fact, sometimes there’s too much to do. And crew need that downtime to rest and recover and be at full performance. And that really comes into the behavioral health aspect as well. And physical performance side too. So, I mean, a giant chunk of every day is going to be taken up by repeat tasks like sleeping and exercise and eating and personal hygiene and communicating with families and friends or just some quiet time. And you might’ve already burnt about two thirds of your day by the time you get there, so with that time remaining, we have to ensure that crew can still complete mission tasks like vehicle monitoring and maintenance and doing science. And when they’re on the surface, going and doing surface exploration and EVAs, in the spacesuits and even preparation for going and doing those EVAs can take a long time.

So with all that in mind, you know, how does CHAPEA help us? It helps us see how crew respond to their daily tasks and overall workload. What stresses does it introduce? How does that affect their behavioral health and performance as well as team dynamics? Analogs can also provide a potential platform to test how those stresses and impacts can be mitigated. Mitigating them is important, cause if we don’t, we could lose that valuable crew time if crew performance isn’t sufficiently supported by the architecture and its corresponding mission concept of operations. We don’t want to plan poorly. Cause if we plan poorly, then we don’t have the crew time we thought we would to do the fun exploration part. So that’s one way analogs like CHAPEA provide valuable insights that can be used in architecture development.

We’re going to learn a little bit about a variety of sub-architecture topics. So logistics was one. Crew time is another, but it all has to fit into that overall architecture. So we really try to knock down the number of knowledge gaps that we have. So analysis for Mars and Mars missions, it’s been going on for decades. A long time. And we’re at the point where we really want to converge into making some of our key critical decisions on Mars architecture. So we have been trying to map out which decisions are more critical if we answer these particular questions. We really reduce our trade space down to a smaller set that we can then focus on and keep moving towards getting a refined architecture that we can one day implement. And there are seven key decisions that we’ve identified and that were included in the recent up update of the architecture definition document. And there’s actually a corresponding white paper about those seven decisions too. So I can talk a little bit more about those if you want to hear about it.

Host: Let’s go into it. Yeah, that’s exciting.

Michelle Courtney: So let’s talk about some of the key Mars architecture decisions. So recently we’ve publicized that there are seven ones that our team is working. And we’re doing that with a lot of integrated support across the agencies. And these decisions are Mars science priorities, initial human Mars segment target state and target state cadence, and number of crew to Mars vicinity, and crew to Mars surface cause those two numbers, they might not be the same number. And the final two are loss of crew risk posture. And finally, the surface power generation technology. And some of these are going to be multi-year efforts. Others may come together sooner. But the point with these is that when we make these decisions, we’re on our way to shrinking the Mars architecture trade space by working through the critical decisions along the path.

Host: Is it more focused on like capabilities? Is it capabilities-focused because not a lot of efforts that we’re doing now are addressing these, so let’s address them now and build out the capabilities? Or maybe it’s broader than that.

Michelle Courtney: Well, imagine you’re starting with a blank piece of paper and you’re trying to work out what you need to know first before you can make a whole bunch of other decisions. These seven decisions are just like that. If we can make these decisions, then we have a place to move on to next. Right now, there will be so many different decisions that we have to make as part of an architecture. But the seven that we’ve identified, these are big, heavy hitters that push us into a direction where we can continue to make decisions and refine down to that architecture. So yes, they have to meet the capabilities and that they absolutely trace back to our objectives. But it’s really about refining our trade base down to a point where we can converge and say, “This is what a future Mars program can look like.”

Host: Going into it, is the Mars architecture team confident in these seven that if you can do that, you know, cause you said we’ve been working on this for 50 years, right? So if we define these seven, it’s robust enough where we at least have the framework that’s not going to change too much over time. Is that really the approach to the seven?

Michelle Courtney: Yeah. So the approach to the seven really came down to mapping out which types of decisions we need to do and which ones end up on the critical path. So if you have a decision that would then impact another 20, or you have one decision that only affects one other thing, you’re going to answer the question that impacts another 20 different things, cause there’s a lot of follow on facts. So by mapping all the decisions and the precursor and flow down relationships, we’re able to identify very, very quickly which ones we needed to answer first. And that’s really where the seven came from.

Host: There you go. You created the map. You understood where those, like you said, heavy hitters, the things that have a lot of decisions trickling down from them. Those are your seven.

Michelle Courtney: There’s a great white paper on this topic. If you’re interested, you can go to the Moon to Mars architecture page at NASA and take a read through that. It’s just a few pages there, but it highlights our methodology and why we picked those seven.

Host: It’s a very easy website to go to nasa.gov/moontomarsarchitecture. There you go. And we’ll put that in the show notes as well. Well good to wrap it up with CHAPEA though. Cause I think, you know, what’s nice as you’re taking this is perspective, I end this with all of our special guests as part of this Mars Audio Log series is talking about this analog in particular, it’s such a large integrated analog. We’ve talked with a lot of special guests from a lot of different disciplines and gotten their perspective. And I wonder from the Mars architecture team perspective, why is an analog like CHAPEA so important for the work that you do?

Michelle Courtney: CHAPEA provides an analog opportunity that’s infinitely more accessible. It’s more cost-effective and it’s lower risk than testing in space. Especially since the number of crew that we can send into space is limited. And since we haven’t identified yet exactly what habitation systems or vehicles will use for Mars, there are some things that we can’t truly learn or test until we take them into space. Especially when you consider things like the effects of zero gravity. But really, there’s a lot we can still do on Earth and that’s why CHAPEA here and other analog environments are really important.

Host: It’s amazing. Coco, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast and diving into Mars architecture, one of my favorite topics. It was such a pleasure to have you on.

Michelle Courtney: Thank you. It’s been my pleasure.

[Music]

Host: Alright, that’s it for Audio Log #9 from Dune Alpha. Thanks for sticking around. I hope you’re enjoying the crew’s journey. This again is the ninth audio log in our series. Tune in once a month to check in with the crew. Check out nasa.gov for the latest on what’s happening in CHAPEA and nasa.gov/podcasts to listen to our collection of episodes as well as the many other shows we have across the agency.

If you want to talk to us on social media, we’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, X, and Instagram. You can use #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea or maybe ask a question, just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. The recordings were sent in from the CHAPEA crew in March of 2024. And we had the conversation with Coco on April 1, 2024. Thanks to Will Flato, Dane Turner, Abby Graf, Jaden Jennings, Dominique Crespo, Anna Schneider, and Laura Sorto. Thanks to Michelle Courtney for taking the time to come on the show. Thanks to Grace Douglas and Jennifer Miller for their efforts in reviewing these audio log episodes. And a big thanks to Kelly Haston, Ross Brockwell, Nathan Jones, and Anca Selariu for sharing their experience for this audience on Houston We Have a Podcast. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.

This is an Official NASA Podcast.