From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

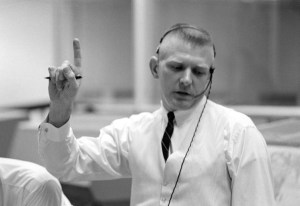

On episode 355, Gene Kranz, lead flight director for Apollo mission 13, discusses leading America to the first lunar landing, his leadership and legacy, and lessons that must be carried into NASA’s future exploration goals. This episode was recorded August 13, 2024.

Transcript

Host (Leah Cheshier): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 355, “White Flight.” I’m Leah Cheshier and I’m your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. We often say at NASA that we stand on the shoulders of giants, of those who paved the way for us to thrive in human space exploration. And today’s guest is certainly one of those giants. You may know him as NASA’s second chief flight director and the lead flight director during Apollo missions 11 and 13. He played major roles through the foundational programs of human spaceflight, like Mercury and Gemini. You may recognize his signature flat top haircut and white vest. He’s not just one in a million or one in a generation. He’s one in all of history. That’s right, everyone, we’re talking about the one and only Gene Kranz.

Gene joined NASA in 1960, becoming one of the most significant figures in the space race, and ultimately leading America to the first lunar landing. Today we’re talking with him about his experiences in the agency, his leadership and legacy, and lessons that must be carried into NASA’s future exploration goals. Let’s get started.

[Music]

Host: Hi Gene and thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Gene Kranz: Leah, it’s really great to be back in Mission Control for the media. You know, this is really a challenge. Many years we spent there addressing the press and this was a real learning curve for all the young flight directors we had. And in fact, the controllers, cause we’d bring them along to the sessions. But this gave us a feel for the other side of the business, and we developed a very strong, firm relationship with our media at that time.

Host: That’s fantastic. We’re going to reminisce a lot today, but I want to talk about the right now, too. So, what have you been up to lately? How are you doing?

Gene Kranz: Well, basically, I just finished cleaning up from the hurricane that we had down in Dickinson. Took a lot of trees down. We lost power and internet, and it’s a real experience to learn to live without all these things you become accustomed to all your life, internet, telephone, TV. But basically, what I’m doing now is I’m in the process of transferring my work history to various facilities. I’ve sent all of my flying gear up Oshkosh, Wisconsin. They’re restoring an aircraft for me up there. St. Louis University came in and they’re getting all my documentation out of my memorabilia. I have the junior high in Dickinson there, the beautiful display area they’ve set up for me. And my home base was Toledo Central Catholic. And that is where the lunar, one of the lunar rock, when I was declared an ambassador of exploration. So basically, I want to get the materials I have out to the young people and provide the inspiration to the next generation, what space is all about.

Host: Yeah. Everybody that will value it. And you’ve really not, I mean, you retired from NASA, but you haven’t really retired in life. You are still so busy. You talk to the interns here; you’ve written some books. What’s that been like passing that on to the future generation and just sharing all of your stories and your lessons?

Gene Kranz: To me, it’s a very simple process. We have six kids and five girls, one boy, and basically five of the six worked in the space program here. And they basically provided the inspiration for me to continue relationship with the young people because they are the seed corn for the future. They are the individuals that are going to pick up and carry the work that we did forward, not only in in space, but basically in medicine and technology, all of the things that came about as a result of the space. So basically, I’m in the process of transferring my work history to the various places where young people will see this and hopefully be inspired and take the risks to become an engineer, a scientist, work in the media, basically address the people of the nation about the business of space.

Host: Amazing. And the books that you’ve written, what’s that like going through that process and deciding what makes the cut and what doesn’t?

Gene Kranz: Well, the first book, I had a contract and basically, I had a word count. I had an editor that was on top of my case all the time. And if they didn’t like what is putting in there, they’d edit the stuff out. The second book is entirely different. It’s self-published, and basically it was a lot more enjoyable read. I had to do a lot of research about my people. I found that in mission control when we moved into the Houston area, our recruiting zone was the Great Plains. And I had a large number of people that came in from various schools, there was one, Southwest Oklahoma State College, that I had three students come in from. I did not know that they were Native American Indians that basically were transferred from the Rosebud Cherokee tribe up in the Dakotas. And they’re working for me now. I had flight directors who became members that had been through the same school. They were farm boys, ranchers. So it was interesting. I learned a lot more about the people, but in particular, I learned more about the people I flew with. So the new book that I wrote has the research. It’s sort of like talking to Gene Kranz across a cup of coffee. And it was a lot of fun to write. I particularly selected individuals to review the people that understood risk. They understood aviation, they understood space. And I had the people who had landed an aircraft in the Hudson River.

Host: Oh, yes.

Gene Kranz: An Australian pilot who had probably the world’s greatest aviation disaster on his hand. He had about 500 people in an airbus, and he managed to save that crew and the people. So it was interesting writing and learning about people as you. I introduced women for the first time, so I had to do some research into the women in the organization. So it was a fun project to me.

Host: Wow. Yeah. So it’s a lot of learning, not just telling. That’s very cool. So let’s rewind a little bit. You’ve always had a love for space, it seems. But a lot of people now, when they go to school, they’ll go to school with this goal in mind of coming to work for NASA. Was that, you know, that wasn’t really an option when you were in school. So what was your goal in the 1950s?

Gene Kranz: I came through a somewhat of a strange path. Basically, my high school thesis was in the design and possibilities of an interplanetary rocket. I was taking people to the Moon when I was a junior in high school. But basically, my love was aviation and flying. I grew up in a military boarding house where we had the soldiers, sailors, and airmen that fought the battles in World War II. And I admired them. My father died, and basically my mother basically ran that boarding house. And this inspired me to chase and pursue aviation. I went to a small aviation school, Parks Air College at that time. And they trained about 10% of the military pilots in World War II. One of whom became an ace, Francis Goreski. And he became my group commander when I was at Myrtle Beach flying the first of the supersonics.

So basically, it was an evolutionary process where first I had the dream of space, but I also had the dream to fly. So, I carried that dream forward. I flew the first three mass produced fighter aircraft, the F-80 Shooting Star, two of the sabre versions and the super sabre, the first of the supersonics I flew in Korea, flew in Taiwan. So I had the opportunity to build a team of young pilots who were basically, my flight that I had during this process. So it was a process of continuing to grow. When I came out, I basically wanted to remain in aviation, but they sent me to a tanker squadron. So I decided I’d move into flight test engineering, and I became a flight test engineer for one of the very first B-52 aircraft, developing the technology that would allow that aircraft to penetrate the Soviet airspace. This is great because I had a shop team. I had instructors in both of these areas that were basically my ideals. Harry Carroll, when was initially in-flight test, taught me all about flight test data reduction. He was a World War II bomber pilot who flew 37 missions. In fact, some of the missions were so risky that one, he brought his crew back alive, they got credit for two missions. Okay. Ralph Sailor was a Marine. Basically, he taught me the process of learning to work. In fact, he used the term, “work with dirty hands.” And I thought, well, what does he mean? He says, “Well, get involved in what your people are doing.” If they’re mechanics, dirty hands of the way to go. And this I carried when I came into the space program because the space program was just beginning. And I got an opportunity, I saw an advertisement Aviation Week Magazine at that time that said they’re looking for qualified engineers to determine the feasibility of putting an American in space. And I thought, whoopee, go for it! That is where I’m going next.

Host: Wow. I can’t imagine seeing that in the paper. And it changed your entire course of your life. But it was obviously a calling like you were born for this.

Gene Kranz: It was a calling. I found it was a calling because when I arrived, I was a member of the first space task group. We were operating in Langley Field, Virginia. And basically, the entire workforce were people who did aircraft flight testing. They developed the aircraft in World War II. They developed the jet aircraft. They developed the first of the jet aircraft that were powered by rockets. So it was interesting to live and work in there because we had a common love. This was, risk is the price of progress, and if you’re going to go faster and further, it’s going to involve risk, and you’ve just got to learn to live with it. And it was to me, an opportunity to grow. But the thing that was amazing was that I was only one of three people who had worked in operations. Every people worked in design and development, but I basically was involved in actually flying the aircraft, testing the aircraft. And when it came time to Project Mercury, we did not have that kind of people. We’d moved down to the Mercury Control Center, and we would borrow engineers to sit in mission control. And they’d be in the mission control room. We’d start trying to train them, and they had never worked with each other before. They had to learn the relationship you had. And after the conclusion of the Mercury program, basically I was given the task to build the team for space.

Host: Well, looking back to then, too, I mean, a lot of people see everything that you did, building that team and, and establishing where we are today at NASA, they see you as a trailblazer and as a leader. But when you’re just starting out and there’s been no one before you in this realm, who were your leaders or your role models?

Gene Kranz: I had many role models, the people who taught me in flight test. But then I also had Chris Kraft. He was the early pioneer. And basically, we were learning the leadership in mission control, both at the same time. I had been in a mission control facility when we were flight testing the B-52, this was new to Kraft. So all of a sudden I became his aid to camp. So by the time that we got to the third or fourth mission, I was, as I was named as his assistant flight director, I thought, “Gee, this is pretty cool.” I been just new job in there, and I’m the assistant to the boss man. But it was an incredible learning curve. And we had so many people we could learn from. Walt Williams was the tough guy who basically developed many of the fighter aircraft and tested them during World War II. But he also basically was the project manager for the X-1 rocket ship that Chuck Yeager flew. So we had this kind of a relationship in the thing that was strange, not strange, but really very beneficial, is from the point that we met in mission control and worked together, we carried all the way through the rest of our life. So basically, we had a team, by the time we got to the Mercury Program, finished the Mercury Program, we knew each other. We were friends, we knew the business. So basically, now we could figure out what it was all about and how we’re going to build people for the future.

Host: Incredible. So much of that work then, the work we do here now at NASA requires trust. And so I look to people that have been here a little bit longer, and they’ve been through missions before, and they can say, “Oh, on the last spacewalk, we did this,” but you were coming in for the first time. You’re all figuring this out for the first time. So how do you build that trust with your team to make the right decisions?

Gene Kranz: To me, the process of stress came from confronting fear and finding the ability to use fear as an instrument to accomplish an objective. And it was very interesting. I had a couple of very difficult times flying aircraft, but every time that I recovered and found my way out of the box I had gotten into, I found myself stronger. And I found that fear is basically an energizer. It basically gets every bone in your body, your mind, going, everything else. How am I going to solve this problem I got? And basically, all of a sudden, fear disappears. And you’re basically oriented towards the solution. And I think that was when I first started building the teams, we’re now moving into the Gemini Program. It was to find those leaders who had faced fear before. I brought in a guy for training, Mel Brooks, who basically had fought as an infantryman in Korea. I brought in John Lewellen, who was a Marine who fought, and they basically withdraw from the Chosin Reservoir in Korea. John Hodge we worked with, he had done flight test with the Avro Arrow there. So these were people that basically worked in very difficult environment. But basically what we did is we established a series of, I won’t say themes brand. We had to brand our teams to this new businesses space. And we did it by when the military, you have an insignia. Well, if you take a look right now, we established an insignia for the teams in mission control. That, believe it or not, has gone on for 50 years with minor modifications. It’s now worn by astronauts.

Host: Right.

Gene Kranz: Okay. We had the foundations of mission control, a call a series of statements, one of which is basically adapt to very young people to always be aware that suddenly and unexpectedly, you may find yourself in a role where your performance, your performance has ultimate consequences. This talks about training people in accountability. You then have a motto where your motto is basically for achievement through excellence. Excellence is the standard. So this is the way you brand an organization. And it’s interesting, this brand still lives today. Over 50 years later. It is in mission control, the foundations in mission control and the walls, we’ve added only one word to it. And this is a result of the Columbia accident, “vigilance” we added. So it’s interesting to basically establish that kind of a foundation. It’s like concrete marble. You cannot destroy that thing because it’s embedded in the people.

Host: Yeah. I agree. I mean, it is on every door in mission control. Before you walk in, you see that insignia, you see what are they, the 10 commandments of spaceflight. It’s, you know, when you enter that room, you know that you leave anything you’re going through at the door, you’re here to do your job. And it’s really refreshing to walk into a room where, you know, everyone is focused on the mission.

Gene Kranz: No, that works. It was the same way with the later in the program when we had the Apollo 1 fire, I created the term tough and competent because I was absolutely killed by the fact that we had lost a crew in the launchpad, and that this should never happen again. So basically, it was to basically establish the mindset accountability for everything that you’re going to do that’s toughness, competence, total and absolute complete preparation where basically you are on top of everything that comes up. And we’ll get into that discussion when we talk about failure’s not an option later on.

Host: Yes. I’ll save a little bit of that for later. So let’s talk about you as a leader a little bit. I mean, you are kind of the apex of what a lot of people see as a leader. So what is something that you think you do well?

Gene Kranz: You know, that’s a challenge. Trying to think about one thing. But it’s basically establish the foundation of trust within the total organization. Because trust is the key element. I have to trust you, you have to trust me. We have to trust the engineers that we had in the program. So this basically relationship must exist in an organization. And it starts at the top. We were very fortunate in the early days where basically had Walt Williams and the crew that crowded in the X-1 rocket ship, trusted him that this rocket ship was going to work, it would perform. Chris Kraft trusted me to act as his deputy, Walt Williams trusted the astronauts that were going to be put in into space. So it’s a question of a relationship that basically can never soften. It is total. And it basically fills, I won’t say every bone in your body. No. It’s the mind. And the thing is that once you’ve established it, you can never back off. You can never lose it. If you do something, you have to walk the talk. When you establish trust in there, you have to walk the talk, because if you don’t, somebody’s going to say, “What’s going on? What’s with Kranz?” You know, he is not the same as I knew him when we were in training. So it’s trust is the key foundation for virtually everything that you do.

Host: I think trust also, not only do you have to have that within your team, and that they’re going to do their job to the best of their ability, but it also means that you can have more open communication, too. If you trust someone, you’re more likely to tell them, “I’m concerned about this issue,” or, “Hey, I need some help here.” If I trust you, I’m more likely to come talk to you when I know I’m having a problem. So I think that’s also really important in the realm of communication, too.

Gene Kranz: The communications are, you know, my first boss, Harry Carroll, and the flight test taught me that basically communications are the key to success in every venture that you’re going to undertake. And it was interesting that when we’re going down to the Moon, I had one final set of words with my team before we locked the doors and went to battle short. I said, “I will stand behind every call you will make. We came into this room as a team, and we will leave as a team.” Then we locked the doors. And from that moment on, the team was ready. They knew that whatever happened in that room, and boy, we had some bad times that day. Basically, we would solve the problem and we would emerge victorious by putting an American on the Moon.

Host: Wow. It’s hard to imagine being in that moment. And so I’m thinking about right now in this world of spaceflight that we are in, I’m trying to find the things that I’ll be nostalgic about someday in the future. So I’m trying to soak up all of these new partners that we’re working with, and as we figure things out and do things for the first time, did you know then just how special and how truly valuable all of this would be in your life and to the rest of the world going forward?

Gene Kranz: No, I never thought about it that way. To me, it was an instant time when we had something needed to be accomplished. And it might be basically recovering from the Apollo 1 fire. It might be Gemini 8. We had a serious problem on board the spacecraft. And we had two ships that had to be with Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott that basically, we didn’t want to take the chance of getting them around to proper landing sites. So he’d come down on the Pacific Ocean. It was a time that when we left the auditorium and our building, that they had the mindset within the members of the team. Never again. We’ll never fail in this way again. So it’s really something that is a key to accomplishing an objective that is high risk. Because risk is the pride of price of progress, and it’s something that demands performance from individuals. It’s something that is unwavering. They are going to accomplish our mission no matter what it takes. So it’s really a blast to live in an environment.

Everybody asks, “Why did you choose this?” And I said, “Well, I like it because everything is black and white. There are no shades of gray. We either go or no go.” And when we’re in mission control, and the test conductor comes to you and says, “Are you go?” You say, “We’re go for launch.” And this is true. When we give the crew the go, you know, in the aircraft operations, fighter operations in Korea, I had a crew chief, and every time I taxied out, he’d give me a hand salute saying my aircraft was go. I did the same thing with a B-52 to the crew that’s in there. And every time we launched a crew, we gave that same go. We were go.

Host: Well, you touched on tough and competent a little bit. And I want to go back to that. What does tough and competent mean to you? Is this a mindset? Is this a culture? Is it just the foundation on which we should build all of our spaceflight? And maybe it’s all three of those things, but how do you see tough and competent?

Gene Kranz: It’s accepting accountability and the toughness, tough means accepting accountability. And this is accountability for everything I did. Everything I taught to my people; this is what I expect from them. They will be accountable in dealing with me. It is the very foundation, the peak performance that you have as an individual in trusting each one another because you need that toughness. You know, if people are going to equivocate, they’re going to work around. They won’t give me an answer. They’re not being tough. And this is one of the things that getting off track here. But I went through three generations of young controllers. And this is one of the things that we had to build into the teams flying the shuttle program. So we established a bootcamp where we went through the foundations of mission control. We went through the insignia, went through the model, but basically the accountability, focusing the accountability, because we depend upon you. I depend upon you. The program depends upon you. We will fail without you. And basically, when you create that, then you go to the next one. Competence. That’s total and absolute preparation for anything that might happen. So the business is that it’s a foundation that moves you to other places.

Host: Do you think that you would ever add anything to tough and competent, or you think it has stood the test of time?

Gene Kranz: No, it’s been tested in many ways. You know, it’s interesting. I had a Special Forces team that adopted that over in Afghanistan.

Host: Wow.

Gene Kranz: I looked at the pilots that I flew with. That was their role. That was their mantra. That was their belief. That was the brand that we had established. And once you establish it, you know, if you’re becoming weaker, so you’ve got to pull yourself back up to the same standard that you had before. That’s the price for admission to mission control.

Host: Well, let’s talk a little bit more about famous quotes. “Failure is not an option.” I mean, we’ve all heard that one. Everyone has heard that one. And we continue to hear that here in the halls of mission control. So how did you arrive at that mantra? Why do you think it’s lasted so long throughout human spaceflight?

Gene Kranz: Well, there are two major themes. First of all, “Failure is not an option,” was created by Hollywood.

Host: I’ve heard this.

Gene Kranz: I had one of my controllers, Jerry Bostick, whose son, he went out to Hollywood and basically, he started working with Imagine Entertainment. He found that Jim Lovell was writing a book, and he basically got Imagine Entertainment to buy the rights to the book. But they didn’t have money to produce the movie. So they had to get a producer in the process of doing this. However, they came back to me, and they asked about this, and I said, “No, tough and competent basically came from my team, the trench team, the trajectory team, and Jerry Bostick.” But basically, it says the right things because that is the expectation that we have for our people. And my real statement was, we have never lost an American in space. We sure as hell aren’t going to lose one. Now this crew is coming home. You’ve got to believe it. Your team must believe it, and we must make it happen. And that was turned by Hollywood into tough and competent.

Host: Oh. Into failure is not an option?

Gene Kranz: And failure was not an option. You know? I’m sorry.

[Laughs]

Gene Kranz: I am getting all wrapped up here. Thank you. Good catch.

Host: I’m loving it. I have chills.

Gene Kranz: Okay. You’re a good teammate.

Host: Hey, that’s what we do here at NASA. Well, what about failure in general? I mean, what does failure mean to you? Does that mean that things never go wrong? Or is failure just not quitting when things don’t go is planned? What does the word mean?

Gene Kranz: There are three ways you can fail. There is what I call a preventable failure, where you recognize symptoms, and you have the knowledge to take actions to correct the problem that you’re faced with. They’re programmatic that are introduced into the program because of some of the program goals might be reduced cost, stay on schedule. Basically, let’s find a better way, an alternative. And the third one are experimental failures. Experimental failures. That is the price of progress. That is where you learn. That is what Elon Musk is doing. And that is actually the way that we worked in developing the Saturn rocket. We tested all up and we found a lot of the problems that we had in the Saturn boosters, Saturn V in particular, but the fact is experimental. You can accept failures in there because it’s a process of learning the program, programmatic or insidious because they’re born by being in a hurry, not taking care. You know, it’s my Boston flight test told me, taught me, to treat every mission as if it was a first mission. The same care, the same detail, rather on the line. How did Apollo 13 begin? It’s very interesting. A change was made to the design of the electrical system to use some power supplies that were down at the Cape to save money. Engineering orders were sent out to the Cape to make changes, and they did, they changed the wire gauge and the spacecraft, many other things. What they missed was a very small sensor in the cryogenic oxygen tank that did not, was not, modified to accept this higher voltage. But that itself wouldn’t do it.

Host: Right.

Gene Kranz: We got in a hurry because we were in a hurry for launch. We had filled the cryogenic tanks with oxygen, and now when we’re getting ready to launch, we boil off the oxygen, but it isn’t boiling off. We run normally warm oxygen through that, a super cold oxygen boil it off, but it wouldn’t boil off. So we turned the heaters on. This is this defective heater. And the heater boils off the oxygen, but in the process, it damaged the insulation. So when we launched, we had a damaged sensor in that oxygen tank. We didn’t pick up programmatic, that design change by one of the vendors. Then we were in a hurry to launch. So these were the kind of things, but fortunately we had a team that was nothing top of a job to work through those very serious decisions and bring a successful, as Fred Haise says, “The mission control team provided a Hollywood ending for Apollo 13.” But these things that mission rules are very important. That is how we control most of the risks of spaceflight. We designed trajectories, like on the Columbia accident, we didn’t have any accidents on the ground. We designed the reentry trajectory. So it goes over low population paths. When we launch overseas, we look at landing sites like Zaragoza, Spain, that are not in high population areas. So basically, we control the risk as best we can in the process of mission design. These are the kinds of failures that basically are preventable. We do it in the mission roles. We can get together with the program manager and say, “Hey, we ought to change that.” But once we get in, during the course of a mission, like during Apollo 11, basically I had all kinds of options to work around communications problem. I had an option to work around if we landed too long, right around the line. Otherwise, we would’ve had an accident. We would’ve gone into a landing air that wasn’t good. These were preventable. We work in the mission rules. So failure is not an option for the mission control teams for these things that if we’re smart enough, we can prevent problems.

Host: I really like that. I’m taking that forward too. So we’ve talked about Hollywood a little bit. Let’s talk about it a little bit more. You have seen your life and your career in several movies and TV shows, most notably Apollo 13. What’s that like to sit back and see yourself played out and to see these pivotal moments of your life on screen?

Gene Kranz: The first time I saw it was very interesting. We were looking at the preview of the movie. And we were over at the theater. And I was sitting next to Ken Mattingly. And I knew at this stage that basically I was going to be introduced. So I slid down in my seat down there and Mattingly gives me an elbow, and he says, “It’s okay to come up.” And I stood up and this is when they walked into the room with the vest. But it was a lot of fun. I liked it because it shows the efficiency and effectiveness of branding a team. That was my wife’s idea. She made scarfs from my pilots over in Korea. And we had the flashiest team. When you see the markings in my aircraft that they’re doing up at Oshkosh, it was a real spectacular aircraft. But basically, I wore this. And when I put on that scarf for the first time, first three flight directors selected, Chris Kraft selected red, John Hodge selected blue. So basically my wife knew that. So she selected your colors white. Let me make you a white vest.

Well, the first day I put it on was in the Gemini 4 mission. And it was all quiet in there running on the line. And I stood up there out ready to go on the shift. And I put this vest on, and my best friend, Dutch von Ehrenfried, the controller started with me in Mercury is sitting next to me. He calls down to the ground controller and he says, “Move all the cameras, focus on Kranz console.” And all of a sudden, I am on television in every TV in mission control, the press corps, NASA Headquarters, everything. So it was the process of the team was born and the team loved it. And you know, it was interesting. I won’t say the media loved it, but basically that gave an opportunity to brag about my team. And the white team people, they didn’t say I was in the flight control. I was in the white team. So it’s interesting to see people catch on. And that white team carried, you know, it’s interesting, the white team got Dave Scott, Neil Armstrong down in the West Pacific in a very difficult location. Okay. We basically did Apollo 11, we did Apollo 13. We did a lot of missions. But basically, it was the white team, and it wasn’t me. It was the team.

Host: I wore my white blazer today in your honor.

Gene Kranz: Okay. I didn’t get that.

Host: I did, I wore it today because—

Gene Kranz: Okay. Got it.

Host: I’ve got White Flight in the hot seat.

Gene Kranz: Leah, you’re great, coach.

Host: Thank you very much. So let’s talk a little bit more about human spaceflight. I mean, you said earlier, what is it? Risk is the price of progress. And I think that’s incredible. Why do we keep taking these risks? Like, why do you think it’s important for us as humans?

Gene Kranz: Well, there are many dimensions to this. I’m now going on 91 years old.

Host: Amazing.

Gene Kranz: And I think back to some of the first automobiles I saw, I saw the old Willy’s automobile, and it was really a little tin can. And basically, that’s what we rode around town in. Pretty soon then manufacturers came out the better engines, new materials in it. Right on down the line, we saw generational automobiles develop. In space, think about what we would do with, about the communications technology we have nowadays. Because when we started in space, basically we used a low-speed teletype. We had to print messages out to sites all over the world. And we taught our controllers, believe it or not, speed printing, how you shape your letter. So when you finish one, you’re ready for the next.

Host: Wow.

Gene Kranz: Okay. So this was what we went, but then pretty soon we had communication satellites. And then we had weather satellites. So risk is the price of progress. There we were the leading edge of risk in many areas. But talk about medicine. I got more mechanical devices in my heart that came up through the groin. I’ve got watchman in there that prevents blood clots.

Host: Yeah.

Gene Kranz: So where do we want to go? Do we want to stand packed, stand still with what we got now? We need to keep moving forward. And space basically provides a path to generate new things because we got tougher problems to solve. The day we go to Mars is going to be a lot tougher than it was getting into Earth orbit. So basically, you have to take the risk to go do this. My concern on that is maybe we’re taking too big a chunk in the first bite. So I think that the key path is to really go back in and look at some of the things that we did in the past that added complexity to the program that we never used.

Host: Like what’s that? What do you think that is?

Gene Kranz: Okay. One of the things is if you followed the shuttle program. The key problems that we had were with thermal control systems. And the thermal control design was such with the tiles. And everything we did in there was for a mission for the DOD. And it was a mission with a fractional orbit that basically we went once around, we deployed something, and we came back to Earth. So we had a very high cross range. Well, this changed the design of the thermal system. The thermal problem. It addressed it electrical power profiles for management of the payload doors. We had all these things. So basically, we carried that scar now through a hundred missions cause we couldn’t afford to go back and rebuild this thing. So I think that there’s some point where I think program management should really address all of the elements and the very complex Artemis program that we’re building. And are all of these things truly necessary? Are they timely? Could we put them off to maybe a later section of the program? So I think they’re foundational because not only does that complexity yet, but it makes for integration problems. The toughest problem that I had that during the Apollo program was putting all the pieces together for the lunar landing.

Now what are the pieces you got? You got two spacecrafts involved. They’re going to be operating together, they’re going to be separated. One’s going down to the Moon. It’s going to carry all kinds of experiments in there running on the line. And I think that fortunately, George Low, after the accident, probably, he was one of the key players that made Apollo success a success. He and Bill Tindall. George Low, recognized that the software was going to be the key to accomplishing the Apollo program. And he was worried about the ability to produce the software in a timely fashion to meet President Kennedy’s goal to land on the Moon before the decade was out. So he got a hold of Chris Kraft and he said, “Chris, you’ve got to do something to basically sit on top of the IBM and the Draper labs people right on down the line.” He says, “You have to integrate all these pieces that got to come together in the flight software.” So Chris got together with a trajectory guy, Bill Tindall. I learned when I wrote my book that he was a board of destroyer in the war in the Pacific in World War II. And he was one of my best friends. We would go to his cottage down on the beach at Bolivar, and I’d ride in the sailboat with him. But basically, Bill was the guy that was given the task to tie all the pieces of the software together, because everybody wanted something different. Astronauts wanted this, flight controllers wanted this, engineers wanted this, cost managers wanted this.

So basically, he tied this together in what was called the data priorities. And the data priorities today, you’d have a meeting that would go on for one in two days. People would argue, they’d yell, they’d scream right on the line. And two days after the meeting was over, Tindall would write a memo that said, we had a long meeting. I heard a lot, I got a lot of input from you guys, but I think this is what we said, what you said, and this is what I think we ought to do. And he wrote out a Tindall-gram and the Tindall-gram, he had humor when he wrote these memos that basically you couldn’t sit back and you say, “God, why did we argue so much about that stupid thing? We didn’t need to.” Well, right now, the Tindall-grams are a document about that thick. And they, everybody that’s worked in the programs, has got a copy of these Tindall-grams. For instance, he got a hold of me. And a very simple thing he says, “You have a series of go no go’s when you’re going down to the Moon. What do you do when you land on the Moon? Are you going to say, “go,” are you going to say “no go”?” And he says, “You need something better. How about stay or no stay?” And that simple word came up saying, we’re going to stay in the Moon. It made sense. But data priorities just a stupid little thing we were saying, we had never thought about it.

When you get down on the Moon, what are you going to tell Armstrong? So anyway, these are the kinds of things that came out of the program. And these are the kind of challenges that Artemis is going to face. Integration and putting all these pieces together. You got the booster, you got the Orion, you got the Gateway. You got basically the sub booster, the big booster that goes down to the Moon. Then you’ve got to get off and you’ve got to, you know, so you got all these things that have to be integrated together. And that is the greatest challenge that Artemis will face.

Host: Yeah. And I think we have a lot of new challenges too, when it comes to, we’re working with commercial partners now. We’re working with other international partners now. So that supports us in low Earth orbit. You know, we do have a good history of that on the space station, but we’re also looking to do that at the Moon. So how do you reflect on those changes and what the future holds for human spaceflight in that way?

Gene Kranz: Wow. You’re ready for an hour. How much? You got a lot of film here.

Host: I’m going to sit back. You go for it.

Gene Kranz: Okay. No, actually I think that there’s many things that we have learned in a man’s spaceflight that were very surprising and wondrously surprising to me. When they first started, I was basically still working when we started putting the first space station modules up. And I was really amazed that they could build systems together that basically without being physically made it in space capabilities. And I say, “Boy, this is pretty neat.” They can build stuff in the Earth and put it in space and it’s going to work, it’s going to fit. Well, the same thing happened in software. All these laptops that are circulating with each other onboard the space station. So I’m absolutely amazed.

I’m absolutely amazed. Now they’re talking about inflatable space systems. So right now, when I think about inflatables, I say, you know, what was the worst thing that would’ve happened to me when I landed on the Moon? The ascent engine didn’t work. We can build a habitat, a safe station on the Moon and put it in place when the crew lands there the first time. Why not? Okay. So, there are several pieces that I think come together and this, you know, we get hung up and I think it’s important to address what is private. Because right now, how you corral all of the contractors that are working in space through some massive change board. I sat change board for the Apollo program and for the shuttle program, and I worked at Huntsville in the CCBs we had down there. As an operator, I was able to grasp the challenge of cost, schedule, compatibility, all the putting these pieces together. And I say that somehow or other, you have to find a way within this contractor organization team, we had the level two boards that we would run. And they were like day long sessions. Sometime two-day sessions. How is this stuff going to be physically come together? You don’t do it through organizations. It’s done through people. And I think the people organizational challenge is going to be the greatest task that the future programs have.

Host: Yeah. I think a lot of people are getting excited about it, getting excited about the future and want to be part of that, which is really encouraging. So, I want to talk a little bit more about you as an icon.

Gene Kranz: Yeah. You know, that got me. For the FAA, basically I was declared the elder statesman. And that was when I was 15 years ago. I didn’t think I was elder then, but it was interesting that I’ve changed the title they give for that award.

Host: Oh, yeah. Well, you’re an icon at least. An icon, a legend. You, Chris Kraft, Bob Gilruth. You’ve left a legacy for NASA and for human spaceflight as a whole. You know, you’ve paved the way for this. So what is your legacy? What do you think the benchmark is that you, that all of these other, you know, icons have left behind, have forged our road and our destiny in spaceflight?

Gene Kranz: I think it would be this here, this a very difficult question because looking back at the same time, you’re trying to look forward is something I was asked to go to Washington to speak to the new administrator after the Columbia accident. And I was somewhat surprised. I sat through a lot of the briefings. I listened to the briefings and then I talked to the administrator, and I was frustrated that the culture, which was addressed in both, I talked to Sally Ride, both in the Challenger accident and the Columbia accident, I think had several weaknesses. And I think somewhere along the line, the culture of sustaining the space program, which is very high risk. It’s high cost, it’s extremely demanding. It is going to be the toughest problem. It’s going to be tougher than building the systems. How do you sustain the culture to give the crews you put on board the spacecraft the same chance at coming home? As I gave the culture to my B-52 when they taxied up, I gave them the best systems I could conceivably provide. That was what my crew chief gave me. That was what we tried to give every crew we launched. And I think how do you build and sustain the culture is the greatest challenge. Not only a space, but many industries nowadays. It’s not easy and it is something that needs to be addressed.

Host: What do you think good hallmarks of those cultures are do you think? It is a lot of the things we’ve talked about, about accepting risk and being tough and competent.

Gene Kranz: When I finished my book, my second book, I took and tried to document all the quotes from everybody I worked with. And that’s the pilots I flew with, Chris Krafts, the people I worked with in flight test, the people I worked with and mission control and put them in there. So there’s a culture, a base, where you could look through down that long listing of things. Part of it relate to expectations that people should have. I look at the foundations that we have established for mission control, which is still there today. It is a foundation I must provide to the people working for me and is their expectations of what I should sustain and basically represent. So that’s building the future. I think it’s time to go back in address.

When I wrote the second book, I wrote it for a different generation. Because the shuttle program had been completed, the space station was up and operating for about 30 years, and they’re moving in a different direction. But programs are run by people and these people have to be provided a foundation. I’ve found differing foundations based on generations. When we brought in the shuttle generation, we established a bootcamp for our people to get people used to extremely long work days. Someone leaning over the shoulder and saying, “Why are you doing that thing?” A level of self-appraisal. Am I tough and competent? Do I demonstrate those capabilities? So I think the future demands more from a culture aspect than it demands from a technology aspect.

I talked to a new administrator who came in up there who was put on a line with Dan Goldin, and he was brought on board to address the dollar problem, financial problem, of the space station program. He inherited the Columbia accident, and it was very difficult for him because he had not been in that environment. And he got a good team of people pulled together. And I wasn’t on the team, but I had communications with people on that team. And Sally Ride and I tagged up on a couple occasions. And, fortunately, the solution came about by making some, what’d say dramatic changes in and how the program was run. They went through four program managers for the space station, which is very interesting. And the first one was addressing the problems associated with the internationals. Get them all speaking the same language. Then they brought Tommy Holloway on to basically address the integration process. So it was interesting. They went through the steps that now took, it was a difficult set, different challenges created because of personnel complexity, inter-organizational complexity, international complexity, financial, and try to address these as set pieces. And they went back through that, and they got a good history on that. You can look it up on the internet and you can look up the, how this program finally came together. But it did. And I think there are so many things that are out there.

People never look at the past because they can learn some of the things that apply to the future. And this is, I think, frustration to all the gray beards, myself, Fred, and on the line, because we had to live with the past from program to program to program because we had the same people carrying us through that program. So that basically, we grew as a family. And this is one of the greatest challenges. There are all kinds of challenges, but basically, the Artemis program has many elements in there that have to somehow or other find this family association. When I was working as a section chief, Chris Kraft sent me up to brief the NASA Administrator on a change I wanted made on board the ships and went up to the administrator, I sat outside his office all day long cause he was busy and he invited me to have supper with him. The relationship that we had was highly personal. We were a team. This is the relationship that has to be established and it is a cultural relationship. I think that’s probably about all I can say.

Host: I think it’s a great challenge and a very attainable one to pursue as we move forward in this new generation of spaceflight with.

Gene Kranz: And I’m teaching an MBA program, really, at Johns Hopkins.

Host: Wow.

Gene Kranz: Okay. And I’m doing that via Zoom. And every session I finish leads to another session to finish. But basically, we’re addressing these issues that you’re not going to learn in college. You’ve got to learn through experience.

Host: Yeah. Truly.

Gene Kranz: So it’s really a question of how do you get the people to really accept the fact that experience is the price of progress. Anyway, it’s a very—

Host: That’s a great point. And I mean, that’s one of the reasons that we wanted to have you here today and to talk about everything that you’ve learned and the things that we can take forward and having these things now that I’ve just learned today about, you know, the beliefs on culture.

Gene Kranz: One of the other things is, no, this was really it. Every time we ran into a problem with the program, we were fortunate. We had a very capable aerospace industry out there. And we could bring in John Yardley from McDonnell Aircraft to basically teach us rookies how to run a program. Basically, we had people we could bring in and work as NASA. They would accept gross pay, cut to work as a government employee for some period of time to teach us this business. Okay. I’ve done enough.

Host: Well, I just want to thank you for joining us today for the conversation. I can’t tell you how much I value everything that we’ve discussed, I’ve taken away things that I think are hallmarks that are easily attainable going forward when we look toward building a culture. I think that’s something we can do. And hearing the importance of how that played into all of the programs that you worked on and how we can, you know, achieve greatness through that and through taking risks and through being tough and competent, I can’t thank you enough for just coming here and sharing it with us. It is truly an honor to sit here with you today. So thank you, Gene.

Gene Kranz: Oh yeah. Thank you for the invite. I pretty much drew a line a few places, but, basically, it’s just really a marvel, this opportunity to talk about the past and how it can be applied to the future. Thank you.

Host: Well, we’re ready. Anytime you want to come back, you always have a seat here.

[Music]

Host: Thanks for sticking around. I hope you learned something new today. If you want to know what else is up with NASA, visit us online at nasa.gov for the latest. You can also continue your audio journey at nasa.gov/podcasts. Reach out to us here at Johnson Space Center on social media through Facebook, X, or Instagram. Just use #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit your idea and make sure to mention it’s for Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded August 13, 2024. Special thanks to Will Flato, Dane Turner, Charles Daniel, Josh Valcarcel, Abby Graf, Jaden Jennings, Gary Jordan, and Rob Navias. And of course, thanks again to Gene Kranz for taking time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.

This is an Official NASA Podcast.