Victoria Garcia

Contents

Personal Essay

My parents emigrated from Cuba when they were young. They had to rebuild their lives from scratch in Miami, Florida. With my parents setting as examples, I was raised with the drive to work hard and reach my goals. I also was very strong willed and independent.Being born profoundly deaf, a female, and an only child, my parents were very protective of me and I wanted to prove to them that I could do anything a hearing man could do. My mom has been the biggest influence in my life. Even though she was protective of me, she has never limited me. She always pushes me to go forward, and never told me what to do or what I should be, only that I should be what I want to be. I have the utmost love and respect for my mom for making me who I am today.

It made sense for me to be an engineer. I loved solving problems and I had a knack for being the “handyman” of the house growing up. I recall replacing a ceiling fan when I was in high school. I also taught myself as much as I could, through books, internet, or DIY projects. At the age of 13, I taught myself QBasic, a simple programming language. One summer, I just couldn’t find a summer job for a month, so I decided to build a hoverboard out of plywood and a wet-vac.

Even though I grew up only about 3 hours away from Kennedy Space Center, I never really took an interest in NASA or space until college, other than a love for Star Trek and Star Wars. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) gave me a very hands-on multidisciplinary college education. I realized that I loved to find a way to solve a practical problem using math/science. To me, the space industry requires a lot of unique problem solving skills since we are going to where “no man has gone before.”

I made good grades, but I was not an A+ student, so I never thought I would be hired by NASA or other space related companies. After graduating with my bachelor’s in Mechanical Engineering from RPI, I focused on applying for aerospace/automotive jobs in private companies. During this time, someone sent me an email about Entry Point, a program focused on giving STEM-related internship/co-op opportunities for people with disabilities. I actually wrestled with myself on whether to apply or not. I worked hard getting through school, so I did not want someone to hire me just because I was deaf. After an interview for a job became extremely awkward because I had a hard time understanding the interviewer, I decided to apply for Entry Point. To this day, I credit Entry Point to getting my foot in the door for NASA.

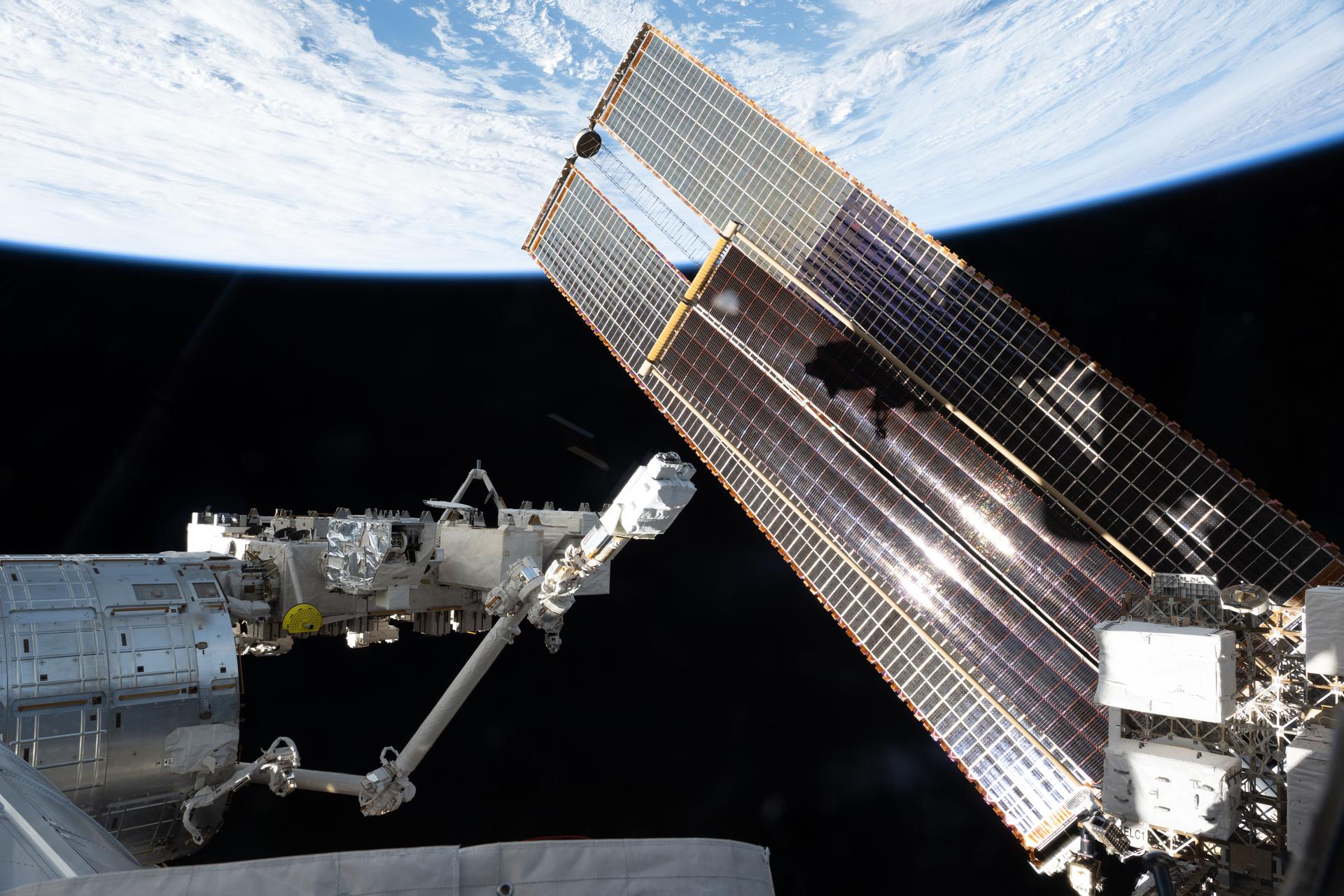

Entry Point offered me a summer internship in NASA/Kennedy Space Center, working with the Fluids team for modules for the International Space Station. It was exciting and inspiring to be working in a high bay filled with modules and flight hardware that will go into orbit. During the internship, I watched my first shuttle launch, which was amazing. After the internship ended, I knew that I wanted to work for NASA in the long run. I got my master’s in Mechanical Engineering in Georgia Institute of Technology and was offered a job in Marshall Space Flight Center in 2008.

Finding a way to work around my deafness has been the biggest barrier in my 5 year career at MSFC. I cannot use the phone but I’ve been lucky in the sense that emailing is the preferred method of communication for most people who work at NASA. Meetings are the biggest obstacles I’ve had to deal with. When I started working for NASA, I went to meetings and got so lost, but I did not say anything because I didn’t want people to exclude me from work. After a while, I knew I couldn’t keep up with the charade, so I went to the disabilities office to see what my options were. They were helpful but not perfect. As I got older and somewhat wiser, I realized that no matter how much I tried to be like a “hearing person”, there will always be limitations. Now I try to take more control and inform others the reality of the situation and offer alternative solutions. It may require some extra time and effort from others, but it gets the job done, and sometimes my solutions are quicker and better than big meetings that can go on for hours.

In life, there are two main things that I have learned. One is to never let other people’s expectations define you. People had low expectations of me with the sole basis that I cannot hear. Many people have told my mom that I will be limited by the infamous “4th grade glass ceiling” that is often heard for deaf kids. The same applies for people who have high expectations of you. I do not let the high expectations pressure me into doing something I may not be able to do, but it does not stop me from trying. Another lesson that I learned is that there will always be barriers in life. How you deal with the barriers make you who you are. There will never be any quick solutions. My advice for the next generation is that it is possible to do what you want and if you encounter a barrier, jump over it, go around it, dig under it, or find another path to your goal.

When I think of happiest moments of my career, I think of all the times that my teammates and I finish a product or get an analytical model working. It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but when you create something and work hard to get it working or completed, there is this great sense of accomplishment, especially when you enjoy doing it.

Biography

Growing up, Victoria Garcia had a knack for being the “handyman” of the family. Being deaf and a daughter of Cuban immigrants motivated her to work hard to prove herself. Today, she uses her problem solving skills performing analysis as a system engineer. Born and raised in Miami, Garcia excelled in science, math, and computers, earning a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Garcia joined NASA in 2008 after earning a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. Her hearing impairment poses a few challenges in the workplace but never stops her from using her technical expertise to tackle some of NASA’s most difficult challenges. Today, she develops analytical tools and methods for the next generation environment control and life support system that will enable explorers to live and work in deep space.