Pamela Marcum

Contents

Email: pamela.m.marcum@nasa.gov

Personal Essay

I’m not quite a coal miner’s daughter, but that culture and spirit of Appalachia, with all of its quirks and virtues, shaped my younger self in ways that I can still identify with today.My family has deep roots in this region, a place where hard and dangerous work didn’t necessarily prevent money from being tight. My parents, married as teenagers and neither having a high school diploma, stretched their dollars by constructing our eastern Kentucky house with their own hands. Their dedication to getting a job done, on time and on budget, and their fearless foray into creative engineering to solve the myriad technical challenges they faced, have served as valuable inspiration in both my personal and NASA lives. My parents taught me Life Lessons #1 and #2, which are: Be obsessively committed to all the responsibilities that you take on in life, and be fiscally responsible. These values are particularly relevant in my job at NASA, in which I am tasked with prudent stewardship of the taxpayers’ money.

Of those I knew who were lucky enough to attend college, nearly all pursued traditional careers in teaching, law, or medicine. No roadmap for becoming a professional astronomer/physicist was available, nor was advice about how to make a living from having such a degree. Access to a planetarium, museum, or even better – working on a science project with a professional in the field – would have made all the difference.Pure serendipity, through a random conversation with a friend who happened to see an advertisement for an undergraduate program, is how I ended up receiving bachelor’s and master’s degrees in space sciences and physics from the Florida Institute of Technology. Until college, I had never been farther from home than a one-day road trip. Boarding that plane alone to the Florida Space Coast – which at the time might as well have been in another country – was among my most terrifying, but ultimately rewarding experiences. Lesson #3 is to be flexible and fearless enough to take advantage of unanticipated career opportunities (even if they significantly alter your originally envisioned direction and/or remove you from your comfort zone). This guideline was used repeatedly in my quasi-“random walk” career path to NASA.

Having graduated from high school just one letter grade shy of straight “A’s,” I couldn’t have anticipated how the lack of advanced science or math classes offered in my school would leave me so woefully ill-prepared for the first year of intensive college curriculum. I began my first chemistry exam, confident that I could recite details for every discovery in chemistry covered by our notes, knew Avogadro’s number to several decimals, and could describe the ideal gas law. The gut-wrenching “D” I received, quickly followed by a few other exam mishaps, properly destroyed my errant idea of what “being a scientist” implied, and instilled a healthy dose of humility.I spent many hours each week in the free tutoring center with talented peers who taught me that true understanding is being able to solve never-before-seen or unanswered problems using not memorization, but logic and creativity, a core capability for any successful scientific researcher. Lesson #4: Science is an inherently collaborative field, and the most successful researchers are those who utilize help from others.

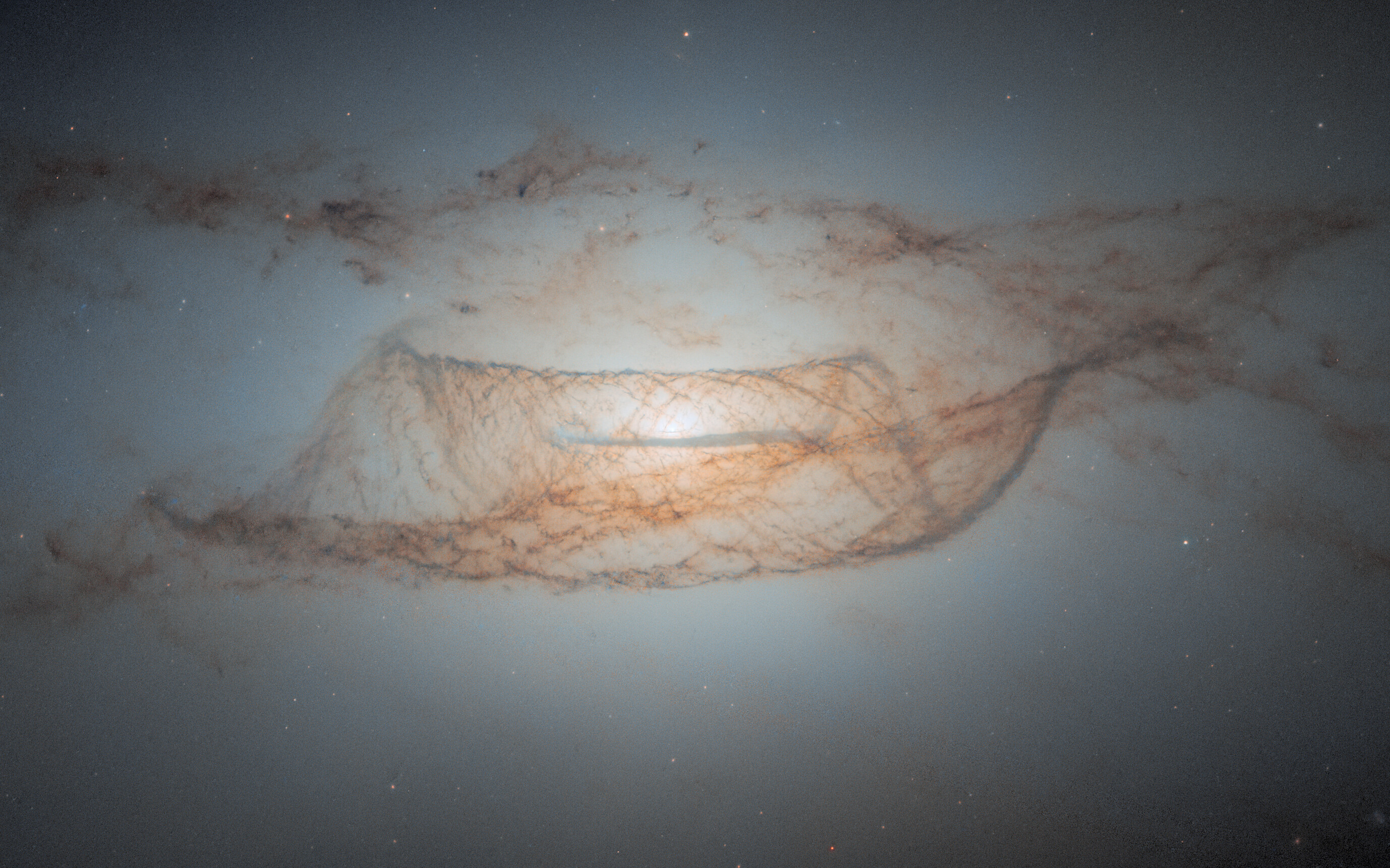

I obtained a doctorate degree in astrophysics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I “began” my NASA career, working on targets and pre-flight calibration for HST/WFPC2. A postdoctoral position at the University of Virginia expanded my NASA experience, where I worked with the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UIT) science team to develop an ultraviolet atlas of galaxies. UIT had flown on the space shuttle-based Astro-2 mission in 1995. After two years, I accepted an appointment at Texas Christian University (TCU) bringing the world of space science to a small physics department.At TCU, I became fully immersed in observational extragalactic astronomy, studying galaxy evolution. I finally had the job that I thought I’d retire from as a tenured professor of physics and astronomy.After about 10 years teaching and developing my research program, I began to feel a bit restless — a kind of professional mid-life crisis. Somewhat impulsively, I applied to a job advertisement for a position at NASA headquarters that had caught my eye. When I was offered the job, I didn’t think twice. The professional growth that resulted, made this the best career decision I’ve ever made.

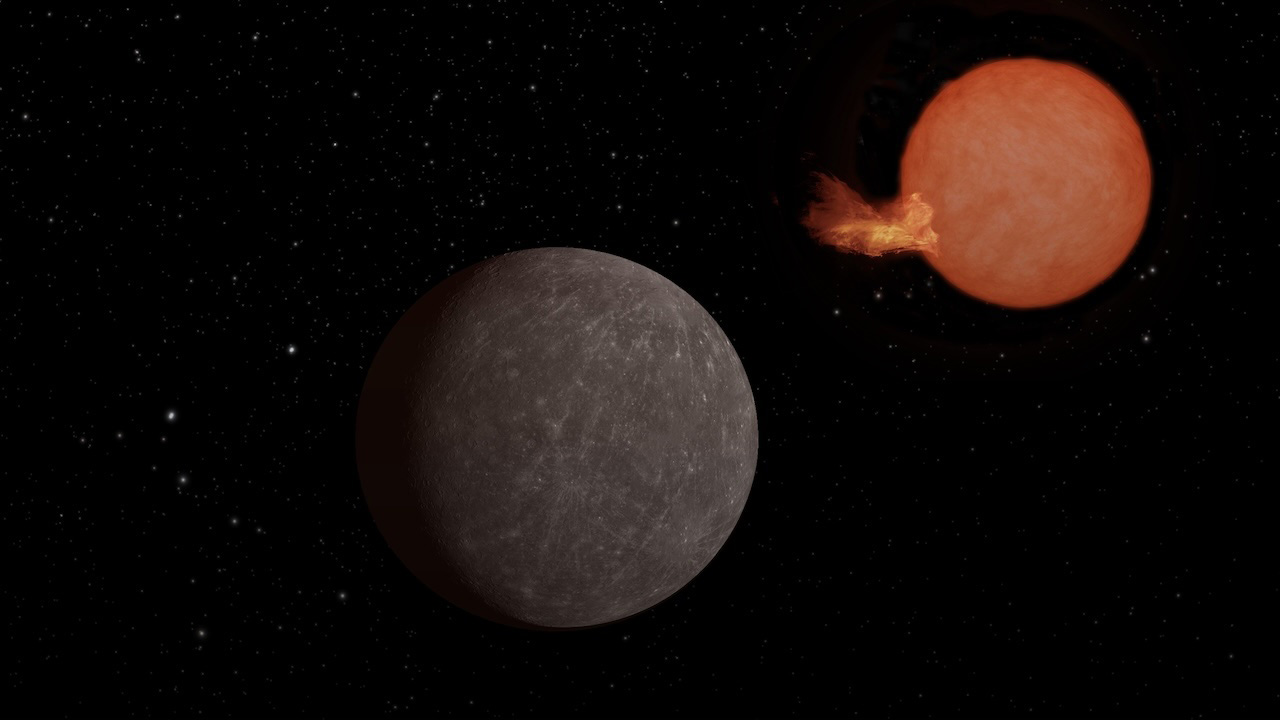

During my three years at NASA Headquarters, I served as the program scientist for two missions under development: the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and the Kepler Mission. I established the Kepler Guest Observer office at Ames and led the first review of the Kepler Participating Scientists Program. One recent satisfying outcome of that program was a press conference announcing the discovery of a “Tatooine-like” planet, led by a PSP. Another responsibility was managing the optical/infrared technology development grants portfolio.Working with such dedicated and talented colleagues, and seeing up close “how the sausage is made,” transformed me.

I returned to TCU in 2008 and made a life-changing career change. Academia no longer filled my professional aspirations and I resigned to return to the NASA family in May 2009 to assume my current position at NASA Ames Research Center as the project scientist for NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).As project scientist, I worked with the team to achieve several major milestones, including the execution of SOFIA’s first science observations, installation of the first flight instruments and an international deployment. During the past year, I have participated in SOFIA “taking wing.” Over the next few years, I look forward to guiding SOFIA towards “spreading its wings” as the observatory approaches full operational capability, with several new instruments, expanded science flights and a growing appreciation of SOFIA in the community.

I didn’t start out knowing exactly where I was headed, much less how to get there. But liberally applying these four life guidelines led to a tremendously satisfying, if not meandering, career. I can’t wait to see what’s around the next bend.

Biography

Pamela Marcum’s journey to becoming a NASA scientist began in a rural coal-mining community in eastern Kentucky. A public school system weak in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) curriculum, and a lack of mentors to provide career guidance resulted in her path being everything but a well-chartered course to a pre-defined destination.An oft-quoted adage claims “the journey is the destination,” and indeed her meandering career path resulted in some valuable lessons learned. Among other things, Dr. Marcum learned that taking on those serendipitous opportunities that occasionally present themselves – the ones that posenew challenges and usually require stepping out of one’s “comfort zone” —is an effective career-evolving strategy. Dr. Marcum received a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in space science and physics from the Florida Institute of Technology. She received her doctorate in astronomy from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she began her ongoing research in observational extragalactic astronomy.As a postdoctoral student at the University of Virginia, she helped construct the first large catalog of nearby galaxies mapped at ultra violet wavelengths, using data collected by NASA’s Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UIT), the only professional astronomical telescope used on the space shuttle.Dr. Marcum later joined the Department of Physics faculty at Texas Christian University (TCU) as the first tenure-track astronomer — and the first woman to be hired in that department.After nearly a decade there, she took temporary leave to become a visiting scientist at NASA Headquarters, serving for three years as program scientist for the WISE and Kepler missions.Following a one-year return to TCU, she left academia to serve as the project scientist for SOFIA at NASA Ames Research Center, where she has worked with the team to achieve several major milestones, including the first science observations for NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).