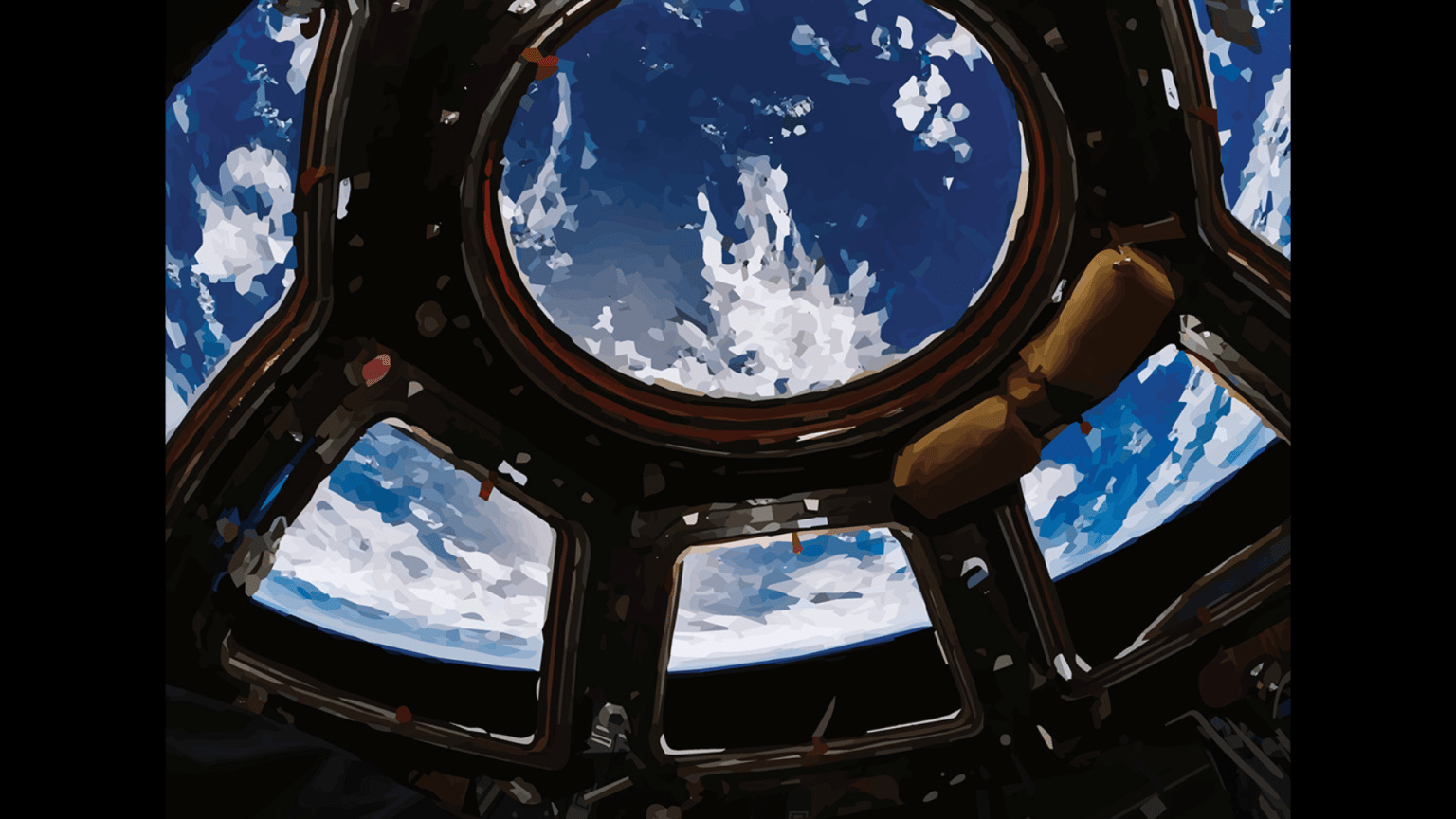

The International Space Station provides unique features that enable innovative research, including microgravity, exposure to space, a unique orbit, and hands-on operation by crew members.

Microgravity

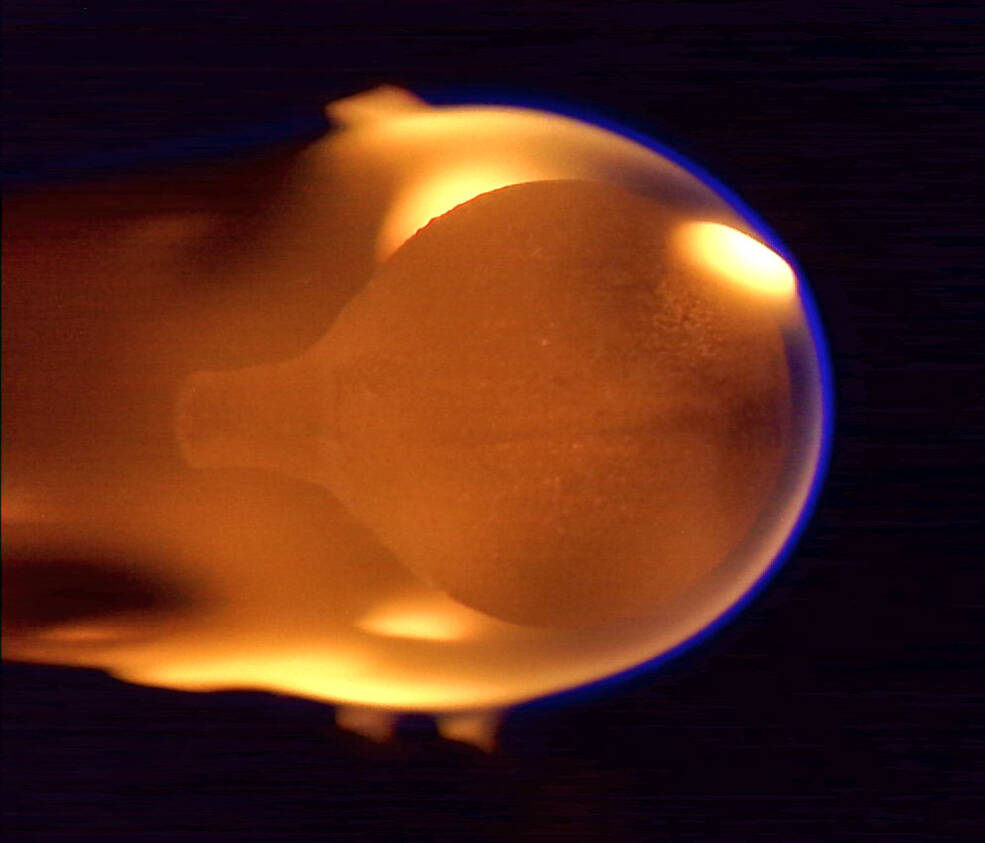

The space station provides consistent, long-term access to microgravity. Eliminating the effects of Earth’s gravity on experiments is a game-changer across many disciplines, including research on living things and physical and chemical processes. For example, without gravity hot air does not rise, so flames become spherical and behave differently. Removing the forces of surface tension and capillary movement allows scientists to examine fluid behavior more closely.

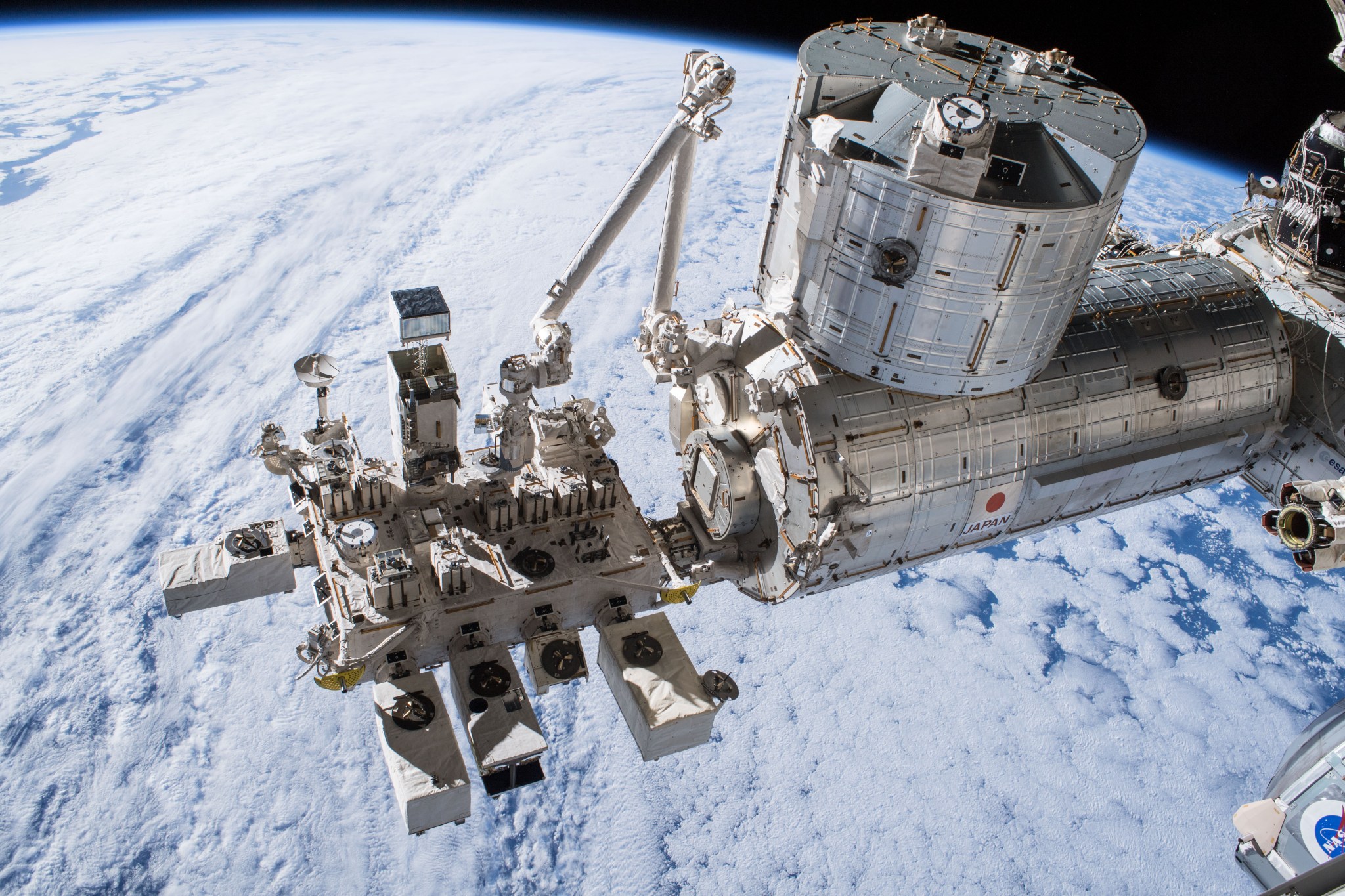

A Unique Orbit

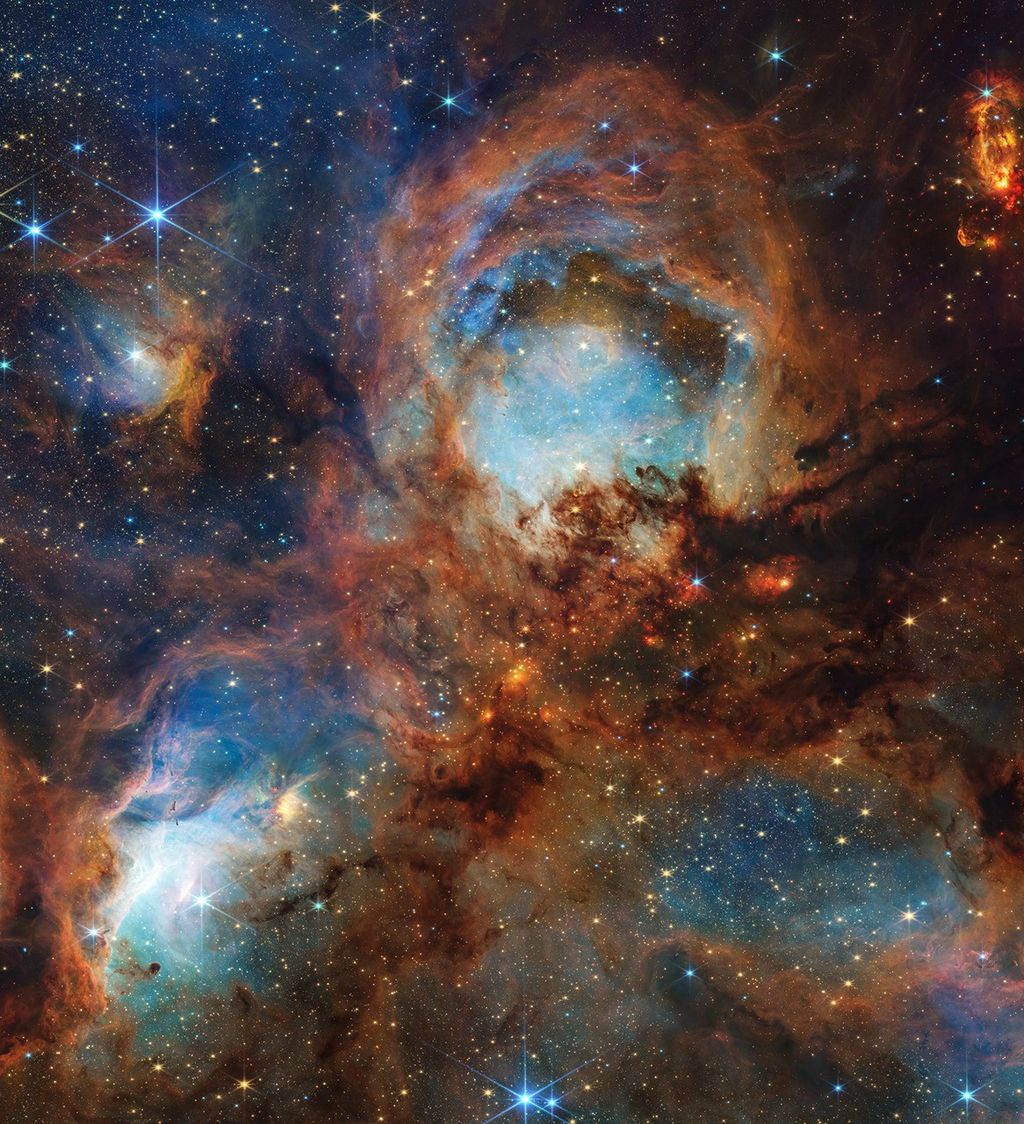

The speed, pattern, and altitude of the space station’s orbit provide unique advantages. Traveling at 17,500 miles per hour, it circles the planet every 90 minutes, passing over a majority of Earth’s landmass and population centers in daylight and darkness. Its 250-mile-high altitude is low enough for detailed observation of features, atmospheric phenomena, and natural disasters from different angles and with varying lighting conditions. At the same time, the station is high enough to study how space radiation affects material durability and how organisms adapt and examine phenomena such as neutron stars and blackholes. The spacecraft also places observing instruments outside Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, which can interfere with observations from the ground.

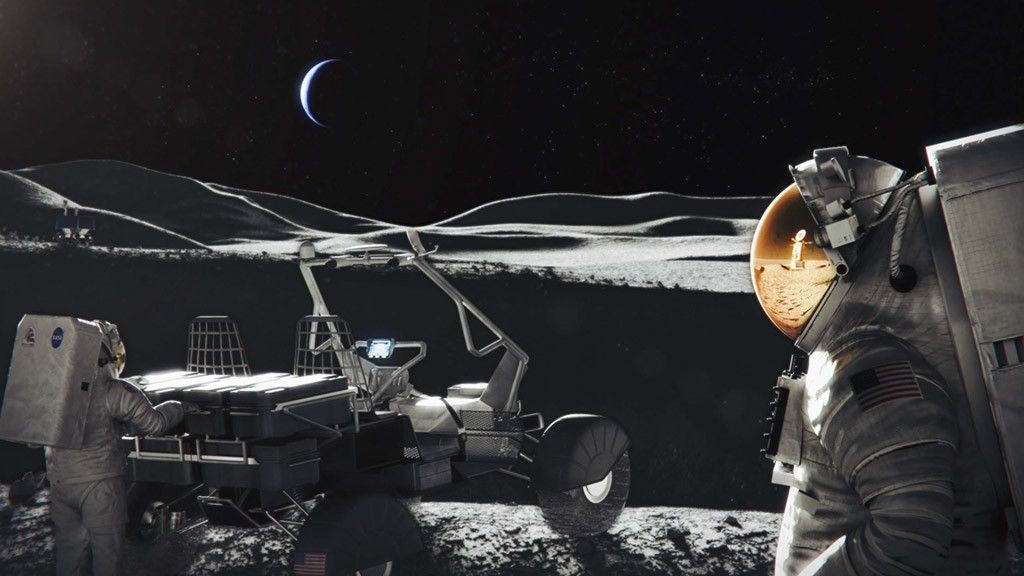

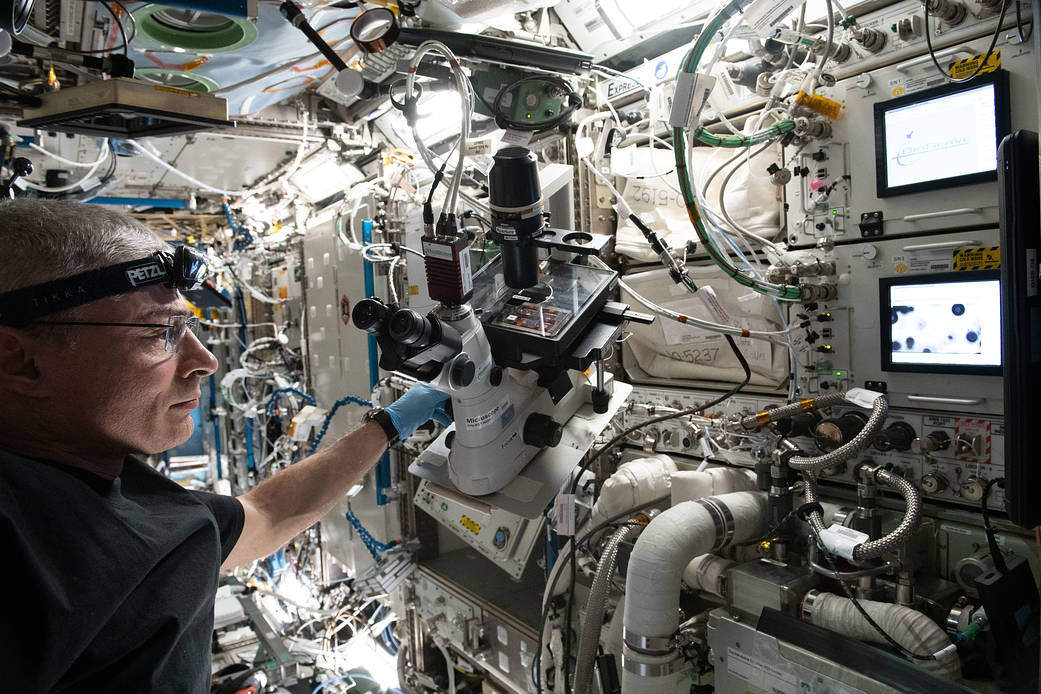

Crewed Laboratory

Other satellites in orbit contain scientific experiments and conduct Earth observations, but the space station also has crew members aboard to manage and maintain scientific activities. Human operators can respond to and assess events in real time, swap out experiment samples, troubleshoot, and observe results first-hand. Crew members also pack experiment samples and send them back to the ground for detailed analysis.

Twenty Years and Counting

Thanks to the space station’s longevity, experiments can continue for months or even years. Scientists can design follow-up studies based on previous results, and every expedition offers the chance to expand the number of subjects for human research.

One area of long-term human research is on changes in vision, first observed when astronauts began spending months at a time in space. Scientists wondered whether fluids shifting from the lower to the upper body in microgravity caused increased pressure inside the head that changed eye shape. The Fluid Shifts investigation began in 2015 and continued to measure the extent of fluid shifts in multiple astronauts through 2020.1

Whether the original study is long or short, it can take years for research to go from the lab into practical applications. Many steps are involved, some of them lengthy. First, researchers must come up with a question and a possible answer, or hypothesis. For example, Fluid Shifts questioned what was causing vision changes and a possible answer was increased fluid pressure in the head. Scientists must then design an experiment to test the hypothesis, determining what data to collect and how to do so.

Getting research onto the space station in the first place takes time, too. NASA reviews proposals for scientific merit and relevance to the agency’s goals. Selected investigations are assigned to a mission, typically months in the future. NASA works with investigators to meet their science requirements, obtain approvals, schedule crew training, develop flight procedures, launch hardware and supplies, and collect any preflight data needed. Once the study launches, in-flight data collection begins. When scientists complete their data collection, they need time to analyze the data and determine what it means. This may take a year or more.

Scientists then write a paper about the results – which can take many months – and submit it to a scientific journal. Journals send the paper to other experts in the same field, a process known as peer review. According to one analysis, this review takes an average of 100 days.2 The editors may request additional analysis and revisions based on this review before publishing.

Adding Subjects Adds Time

Aspects of research on the space station can add more time to the process. Generally, the more test subjects, the better – from 100 to 1,000 subjects for statistically significant results for clinical research. But the space station typically only houses about six people at a time.

Lighting Effects shows how the need for more subjects adds time to a study. This investigation examined whether adjusting the intensity and color of lighting inside the station could help improve crew circadian rhythms, sleep, and cognitive performance. To collect data from enough crew members, the study ran from 2016 until 2020.

Other lengthy studies about how humans adapt to life in space include research on loss of heart muscle and a suite of long-term studies on nutrition, including producing fresh food in space.

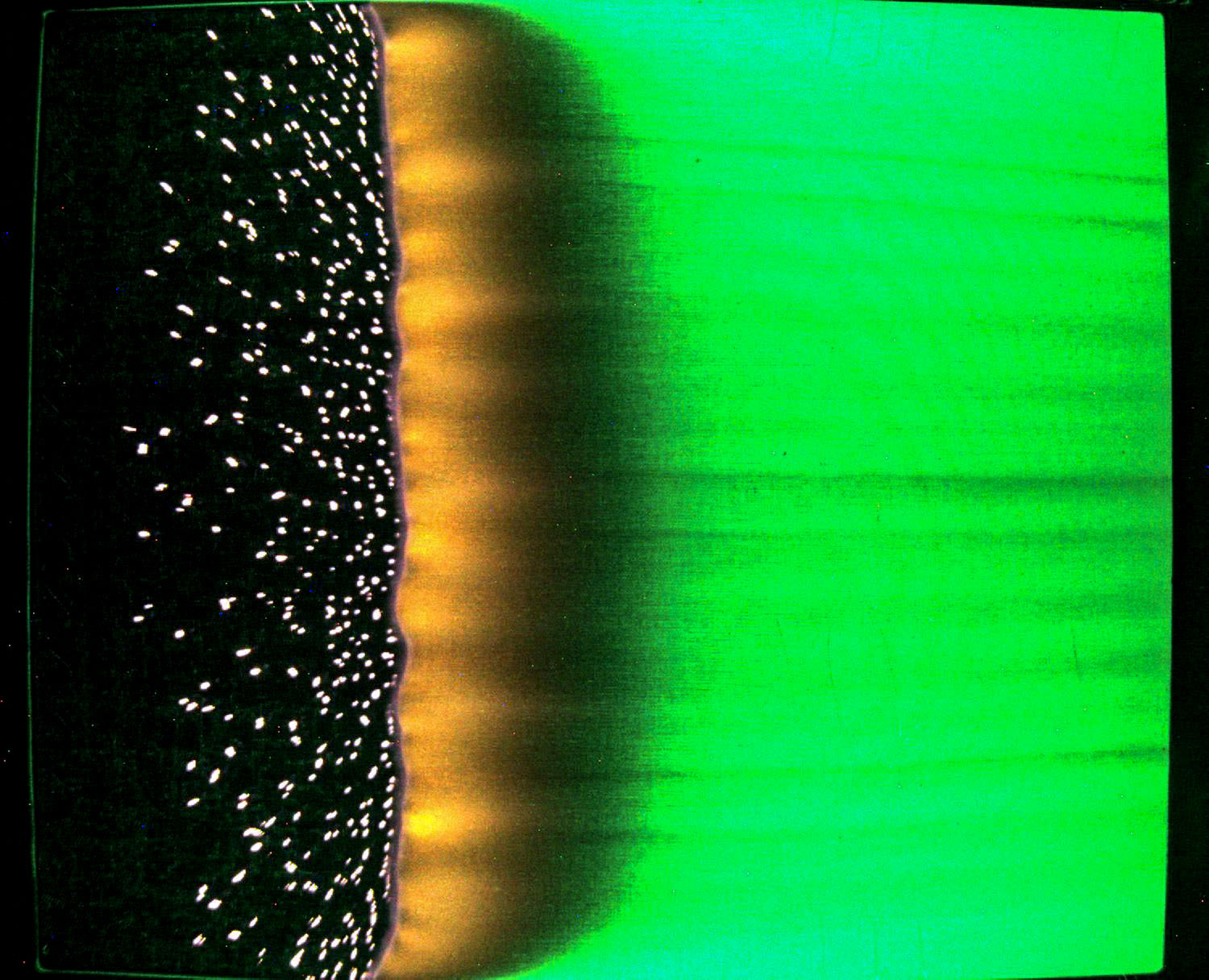

For physical science studies, investigators can send batches of samples to the space station and collect data more quickly, but results can create a need for additional research. Burning and Suppression of Solids (BASS) examined the characteristics of a wide variety of fuel samples from 2011 to 2013, and BASS-II continued that work through 2017. The Saffire series of fire safety demonstrations began in 2016 and wrapped up in 2024. Researchers have answered many burning (pun intended) questions, but still have much to learn about preventing, detecting, and extinguishing fires in space.

The timeline for scientific results can run long, especially in microgravity. But those results can be well worth the wait.

Melissa Gaskill

International Space Station Research Communications Team

Johnson Space Center

Search this database of scientific experiments to learn more about those mentioned above.

Citations:

1 Macias BR, Liu JHK, Grande-Gutierrez N, Hargens AR. Intraocular and intracranial pressures during head-down tilt with lower body negative pressure. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2015; 86(1):3–7. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asma/amhp/2015/00000086/00000001/art00004;jsessionid=31bonpcj2e8tj.x-ic-live-01

2 Powell K. Does it take too long to publish research? Nature 530, pages148–151 (2016). https://www.nature.com/articles/530148a