Mary Walker

Roman Space Telescope Wide Field Instrument Manager

“When I was a little girl, I watched the Moon landings and thought, ‘I want to do that!’” After more than 40 years of working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Mary Walker reflects on her path to and through NASA. Her storied career intertwines tragedy and triumph, with an insatiable curiosity underlying it all.

A Segue to the Stars

Mary knew she wanted to work at NASA from a young age. She always liked building things, taking things apart to see how they worked, constructing with blocks, and playing with electrical circuits. She even imagined herself as a young Robert Goddard (American rocketry pioneer) when she sent model rockets soaring into the sky.

“I was good at science and math in high school and decided to study aerospace engineering in college,” Mary says. “People would always ask why I didn’t want to become a teacher instead. And plenty of people said, ‘Well you’re a girl, you’ll never do it,’ but I took that as a challenge.”

She attended the University of Maryland-College Park at a time when there was no women’s bathroom in the engineering building. And while some instructors were ingratiating, others were harder on her for being female.

But as a junior, she applied for a cooperative education program that would allow her to work at Goddard while finishing school.

“I got it and never left Goddard!” she says.

During the co-op program, Mary worked for the sounding rocket program doing both hands-on work and flight performance analysis. “We did both trajectory and structural analyses to make sure that the rocket performed successfully,” she says. “I was immediately applying everything I was learning in school.”

She graduated magna cum laude and officially launched a career at Goddard.

Highs and Lows

Mary worked in different capacities early in her career and soon became a thermal engineer for payloads that were sent up on the shuttle.

One of them never made it to space. The payload –– a satellite called Spartan –– went up on the Challenger shuttle as part of the STS-51L mission in 1986, but it was lost and the crew died tragically when the shuttle broke apart shortly after launch.

“In the days following the disaster, we had to sequester all of our data as part of the failure investigation while also grieving the loss of a truly amazing set of human beings,” Mary says. “Later I just threw myself into the work, and I think it helped to continue on and not go out on that note. I was able to build up positive memories too, like seeing a subsequent successful Spartan launch.”

Spartan was designed to be placed outside of the shuttle, and the shuttle would back away for a day while all the science happened. That included coronagraph studies of the Sun, experiments exposing different instruments to the environment of space, and radio astronomy.

She advanced to the role of integration and test manager for a mission called the Spartan OAST Flyer.

Mary considers the mission a career highlight because it was exciting work, they did everything right despite a low budget, and it yielded important results. She says it was also very rewarding to work with astronaut crews. “It was a full circle moment, taking me back to when I watched astronauts land on the Moon and was inspired to work at NASA in the first place.”

Following her work with Spartan, Mary worked for 10 years on the POES (Polar Operational Environmental Satellite) project –– first as instrument systems manager and then as the deputy project manager for the final POES satellite. This, too, was marked by both tragedy and triumph; when that final completed satellite was on a turnover fixture, it crashed to the floor due to a mixup with the bolts that were supposed to hold it in place. Mary recalls picking up the pieces, both literally and figuratively.

“I saw the worst of it, but then was able to see the rebuilt satellite go on orbit and send back excellent data,” she says.

To Bennu and Beyond

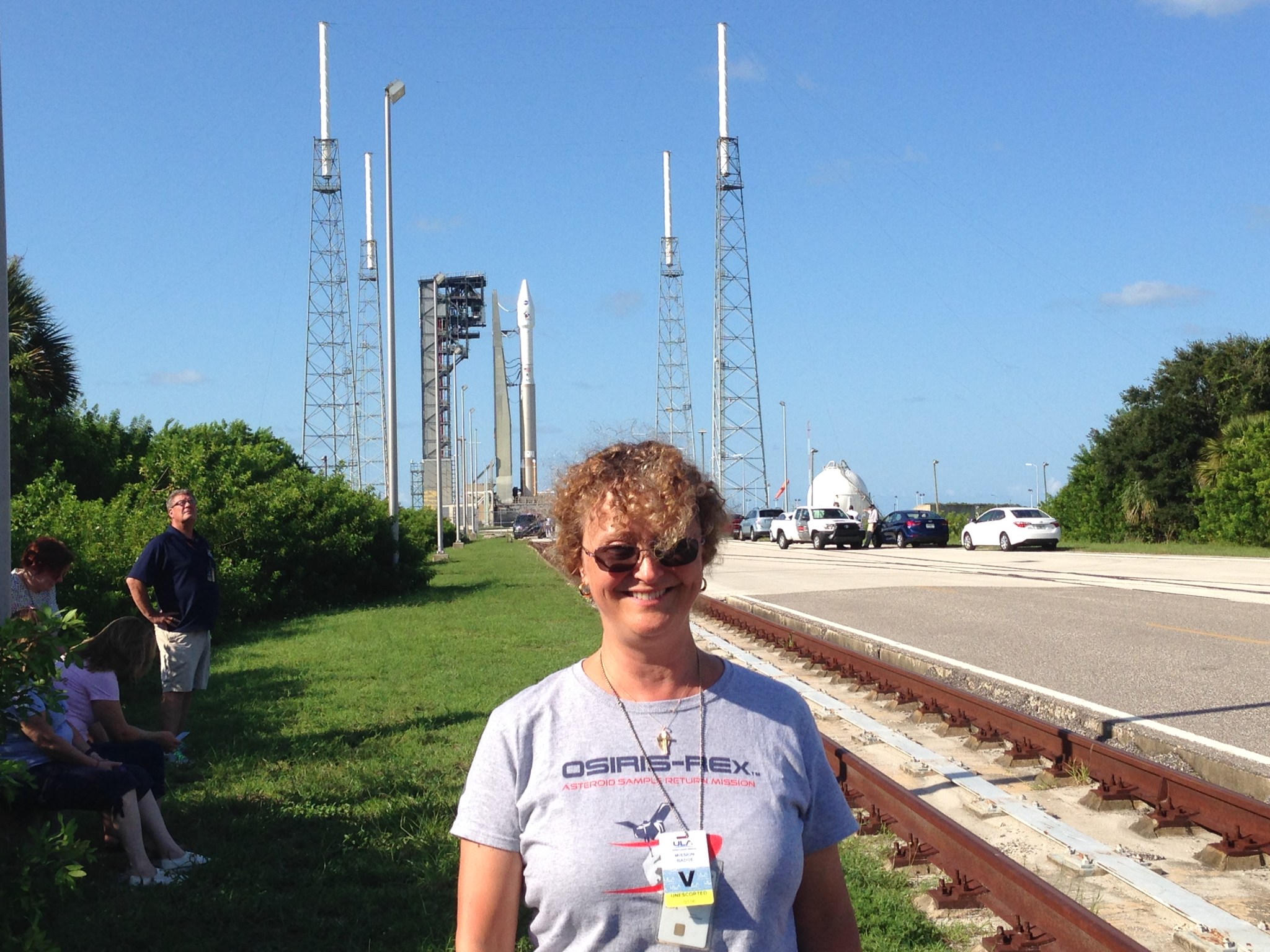

Next, Mary became the payload manager for all the remote sensing instruments on OSIRIS-REx (the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security – Regolith Explorer) –– a mission to collect and return a sample from asteroid Bennu. She was involved in the project all the way from the proposal phase to launch.

Unlike all the previous projects Mary had worked on, OSIRIS-REx aimed to go far beyond Earth’s orbit. That meant it had a very precise launch window –– just one month, so there was no room for delays. And the clean room protocols were next level.

“Contamination was a huge concern because we didn’t want to send life there and think we’d discovered it!” Mary says. The sample was successfully returned to Earth on September 24, 2023.

Then, Mary became the instrument project manager for the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope’s WFI (Wide Field Instrument). Roman is designed to survey large swaths of the sky in infrared light and will look at billions of cosmic objects to explore how planets, stars, and galaxies form and develop over time.

Mary is in charge of the main science instrument that will make this all possible. Her work, like many people’s, was completely upended during the pandemic.

“It really changed how we did business and created a lot of extra work,” she says. “We had to weigh safety against a need to get work done, and the supply chain was a mess. And there was an emotional component in taking care of people during such a tough time.”

Her role is soon drawing to a close, as the WFI was delivered to Goddard on August 7, 2024. At that point, she says she could shift to managing other levels of assembly –– but instead, she’s ready for retirement!

Her plans? “I’m going to sleep! And when I wake up from my hibernation, I want to spend more time with family, volunteer, travel, read a book –– do all the things I haven’t had time for!”

And a well-earned rest it will be. Mary’s work has enabled new technologies and exciting science, and her legacy –– Roman’s WFI –– will send back data for many years to come following the mission’s launch by May 2027.

Perhaps her most important impact will be instilling a similar sense of curiosity and exploration in others. Her best advice is to offer opportunities with no pressure, as she did with her own children.

“We aimed to stretch their minds by exposing them to STEM activities in both formal and informal settings, but without pushing them to do things they weren’t interested in,” she says. “My kids said our dinnertime conversations inspired them the most. We’d talk through the kids’ questions about things like how a plane flies. There was an openness that let the kids ask and explore, which are things we could all stand to do a little more!”

By Ashley Balzer

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.