John Noble Wilford

Reporter, Times Magazine

John Noble Wilford has always been a name to conjure within the rarefied world of space reporting. Whether it was a quirk or prescience, he was born on the date, October 4, the same day the first launch of an artificial Earth satellite.

Wilford has been retired as senior science correspondent for The New York Times since 2009, but he still writes occasional pieces, mostly on archaeology and paleontology, for the Times.

Wilford covered launches from Cape Canaveral and NASA’s Kennedy Space Center from 1965 to 1998, the return of John Glenn to orbit being his last. This period included most of the Gemini missions, all of Apollo, Skylab, Apollo-Soyuz, and the early flights of the space shuttle; not to mention test flights, unmanned launchings to the planets, and other calls to action. He says, “For several years in the 60s I spent more time at the cape, Houston and Pasadena than at my home base in New York.”

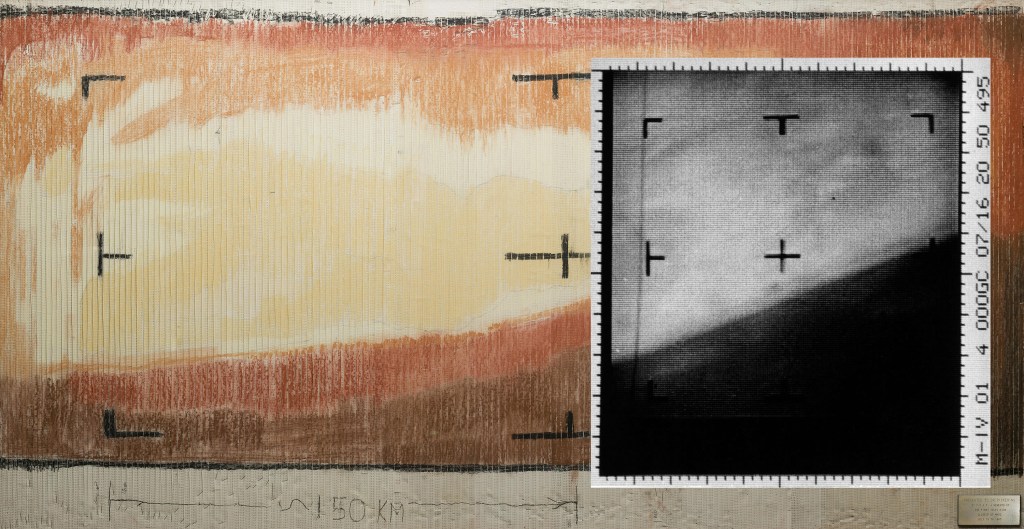

“I had my first taste of space journalism at Time magazine, where I became a science editor and wrote several cover stories, in particular the Mariner 4 fly-by of Mars, followed by Christ Kraft and Mission Control, both in the summer of 1965” Wilford said. “These pieces came to the attention of New York Times editors, who lured me into their fold expressly to cover the Apollo moon project.”

There was a hiatus in the 70s, during which Wilford spent six years as an editor, first as an assistant national editor, then as the director of science news at the Times. “But I decided I preferred reporting and writing over managing and editing, and so went back on the road as a science correspondent, covering space and then spreading out to cosmology, paleontology, archaeology, and various other interests,” he said. “My articles on science, including planetary exploration and “Star Wars,” earned me the Pulitzer Prize in national reporting, in 1984. I was a member of the Times reporting team that won another Pulitzer in 1987, for coverage of the aftermath of the Challenger explosion.”

“Like most aging journalists, I carry into the twilight an overload of memories of the big stories,” Wilford said. “Getting up too early, going to bed too late. Eating and drinking at Ramon’s and Bernard’s Surf. Listening to the then-old-timers tell their burnished tales of the good old days of swarming mosquitoes, oppressive humidity, rockets that fizzled, and the long February wait to see Glenn off on the first American orbital flight. These were our initiations into the space press cult. The tandem flight of Gemini 6 and Gemini 7 was my first mission here. I was hooked.”

“Those were our days of page-one and prime-time glory,” he said. “The pressures were trying, but we couldn’t imagine doing anything else or being any other place. We had plenty of help from NASA….but not invariably.”

“At the end of each Gemini mission, for example, when we pressed for the date of the next one, officials gave us a run-around, saying only ‘in the next quarter.’ The Russians probably already knew the exact date, as did every hotel manager in Cocoa Beach, on whom we had to rely for making our reservations,” Wilford said.

There were reasons we sometimes spoke of NASA meaning, Never A Straight Answer. But most of the time we were loaded down with briefings, news conferences and press kits. Again, there were exceptions,” he said. “The most frustrating were the news “blackouts” after the Apollo 1 fire and the Challenger failure. These tested our reportorial abilities to work outside official channels and break the news that was being withheld from the public.”

“My most indelible memory, of course, was the Apollo 11 launching on the first flight of astronauts to a landing on the Moon,” he says. “On the 40th anniversary, I emerged from retirement to write a piece of personal remembrance for the Times. I began with the drive out to the space center, in the middle of the night.”

“It is close to midnight and the summer air is warm and still, no heavier than usual for Florida,” Wilford said. “We are up early driving toward a light in the distance. Its preternatural glow suffuses the sky ahead but, strangely, leaves the land where we are in natural darkness. After the first checkpoint, miles back, where guards inspected our badges and car pass, the source of the light comes into view. The sight is magnetic, drawing us on. Strong xenon beams converge on Pad 39A, highlighting the mighty Saturn 5 rocket as it is being fueled.”

“The humid air plays the bright light and the venting vapors of the rock’s cryogenic propellants to curious effect. Something like white tissue paper appears to levitate just above the launching pad. On second look, an invisible hand is parting gift-wrappings, esposing a splendid ornament of technology,” he said.

“Anticipation sharpens the sense in the hours leading up to any spaceship’s liftoff. I have known these feelings before, but never so intensely as now. Soon I will worry about the machinery inside the rocket, the plumbing and wiring, and the three men who will be in the capsule atop the combustible load of fuel, everything that has to go right but might go wrong. I must not think of such things, not yet. Let the engineers attend to the Saturn V. Let me savor for a while longer the edgy thrill of driving toward a singular moment in history,” he said.

Wilford also wrote several books, including “We Reach the Moon,” “Mars Beckons,” “The Riddle of the Dinosaur” and “The Mapmakers.” Perhaps more will follow.