Chris Butler

Reporter, Missile & Rockets Magazine

These are vignettes from the life story of a man who refused to reveal classified military information; who exposed shenanigans in the award of I-95 building contracts; and who declined a direct commission in the army in World War II. They are events that remained very private to Chris Butler until his death from pancreatic cancer on Jan. 25, 1965 at age 51.

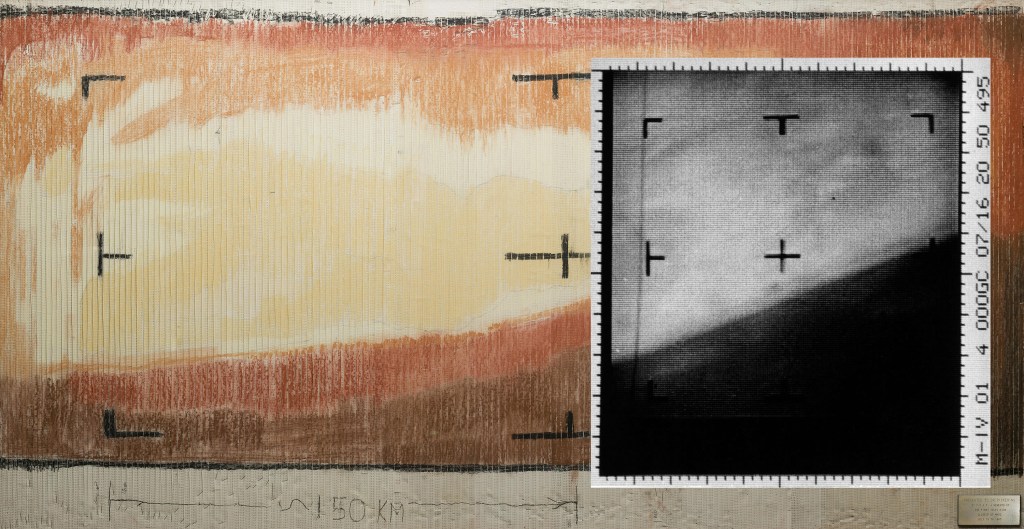

Chris Butler, Florida bureau chief of Missile & Rockets Magazine, refused to write a story revealing details of the secret armada being assembled at Patrick Air Force Base on the eve of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. “I’m an American first and a reporter second”, Butler told his editor and missed out on an award.

Earlier, Butler had exposed the secret agreement by a Florida governor to delay construction of 20-mile increments in I-95 to protect the Florida Turnpike bond holders. The scandal expedited completion.

Butler’s journalistic career also led him to expose illicit gambling and houses of prostitution in what was wide-open New Orleans and Plaquemine Parrish. At one time, New Orleans Item’s editor, Clayton Fritchey, sent Butler on a long “vacation” across the state line to Mississippi so he wouldn’t be forced to testify before a Grand Jury. Butler had hidden in a rusty barrel outside a gambling joint, using his miniature camera to document cops counting their payoffs.

These varied exploits came about largely by chance. After putting four orphaned younger siblings through college, there was no money left for Butler’s formal education. But he was both talented and lucky. He was invited to clerk for a little know Missouri senator and gained experience not available in a classroom.

Although he was offered a direct commission in the army, he turned it down and enlisted as a private. He earned his lieutenant bar in officer candidate school and as a newly minted “second looie” was shipped to England. Butler found his commanding officer unusually solicitous. Were his quarters ok, he was asked, and how was the chow? Butler soon found out why. When the senator, now President Harry S. Truman, called up to ask how his “boy, Chris” was doing because his aunt and uncle back on the farm in Missouri hadn’t heard from him in a while, there was a lot of bowing and scraping and assurances his promotion to 1st Lieutenant would be coming through.

Butler was as adept with a camera as he was with a pencil and paper and was in the vanguard of photo journalists who excelled with a 35mm Leica instead of the cumbersome Speed Graphic.

After his discharge from the army, he became chief photographer for the “Stars and Stripes” in Europe. On one assignment Butler covered displaced persons being herded back behind barbed wire to prevent them from immigrating to Palestine. He “mistakenly” handed over to the British camp commandant several rolls of film having nothing to do with the deplorable event and so preserved the real photos for an expose in the newspaper. The resulting story in the Stars and Stripes and other media outlets helped change the repressive policy.

Butler did remember one failure: He was on the stakeout team trying to catch some big-time Nazis; but they eluded capture.

Life after the war was just as exciting for Butler. He imagined himself sitting on the sands of Kitty Hawk, putting chains on propellers for a flying machine. Instead he devoted himself to spending a lot of time on the sands of Cape Canaveral reporting the early space program with the support of his journalist wife, Sue Butler.

Butler is survived by Sue and their daughter, Penny Bowman, who inherited her dad’s bent for flying machines. She and her husband, Ray, built and fly their own helicopter.