Bill Hines

Reporter, The Washington Star

Bill Hines was an unchallengeable pioneer in the field of space journalism having followed that path of news writing from 1955 to 1989, first with the Washington Star and later with the Chicago Sun Times. His interest in the field was sparked by the then-President Eisenhower’s announcement on July 29, 1955, that the United States was planning to launch “small earth-circling satellites as part of [its] participation in the International Geophysical Year” of 1956-57. As Sunday editor of The Star at the time, he decided to do a major takeout on the project, its meaning and its mode of action. Coming out within a week of the president’s announcement, the piece, leading the Sunday editorial section was among the first of its kind to see daylight.

Shortly after this maiden effort and seeing an almost limitless beat ahead, Hines asked to be reassigned from desk jobs to succeed Tom Henry, who was about to retire as science editor. At first his boss, Newbold Noyes, scoffed at the idea, pointing out that he would be giving up a place on the executive ladder for a “back-of-the-paper” assignment to which Hines offered the counter-argument that within four or five years the government would be spending more each year on space than it had spent on the whole Manhattan (atomic bomb) project of World War II. The rest, as they say, is history.

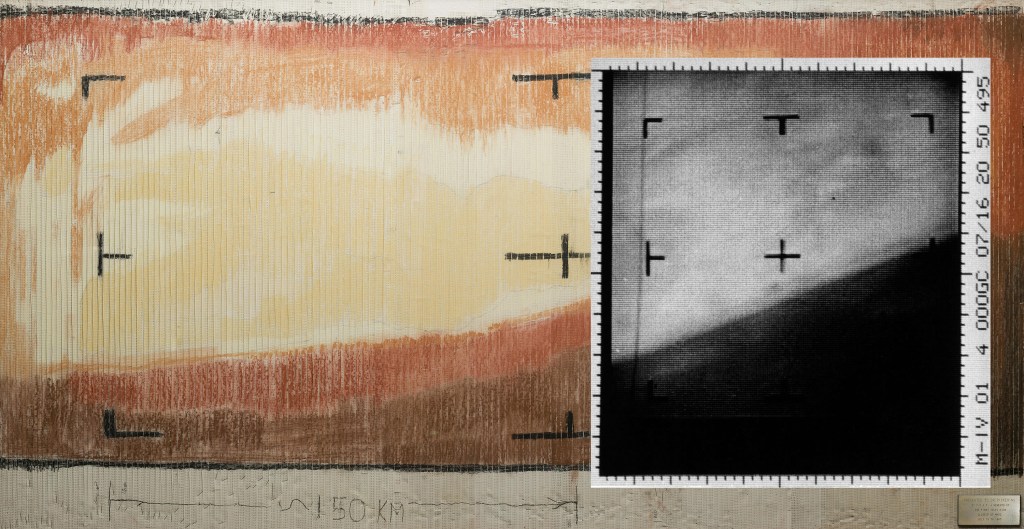

Over the next 30-odd years, Hines was “in at the creation” of every major development in the space program and most of the minor ones-from the establishment of NASA and the unveiling of the Mercury Seven astronauts, heralding the birth of the manned space flight program, and the start of unmanned interplanetary exploration to the completion of Project Apollo and its sequels and of the trans-solar-system Voyager program.

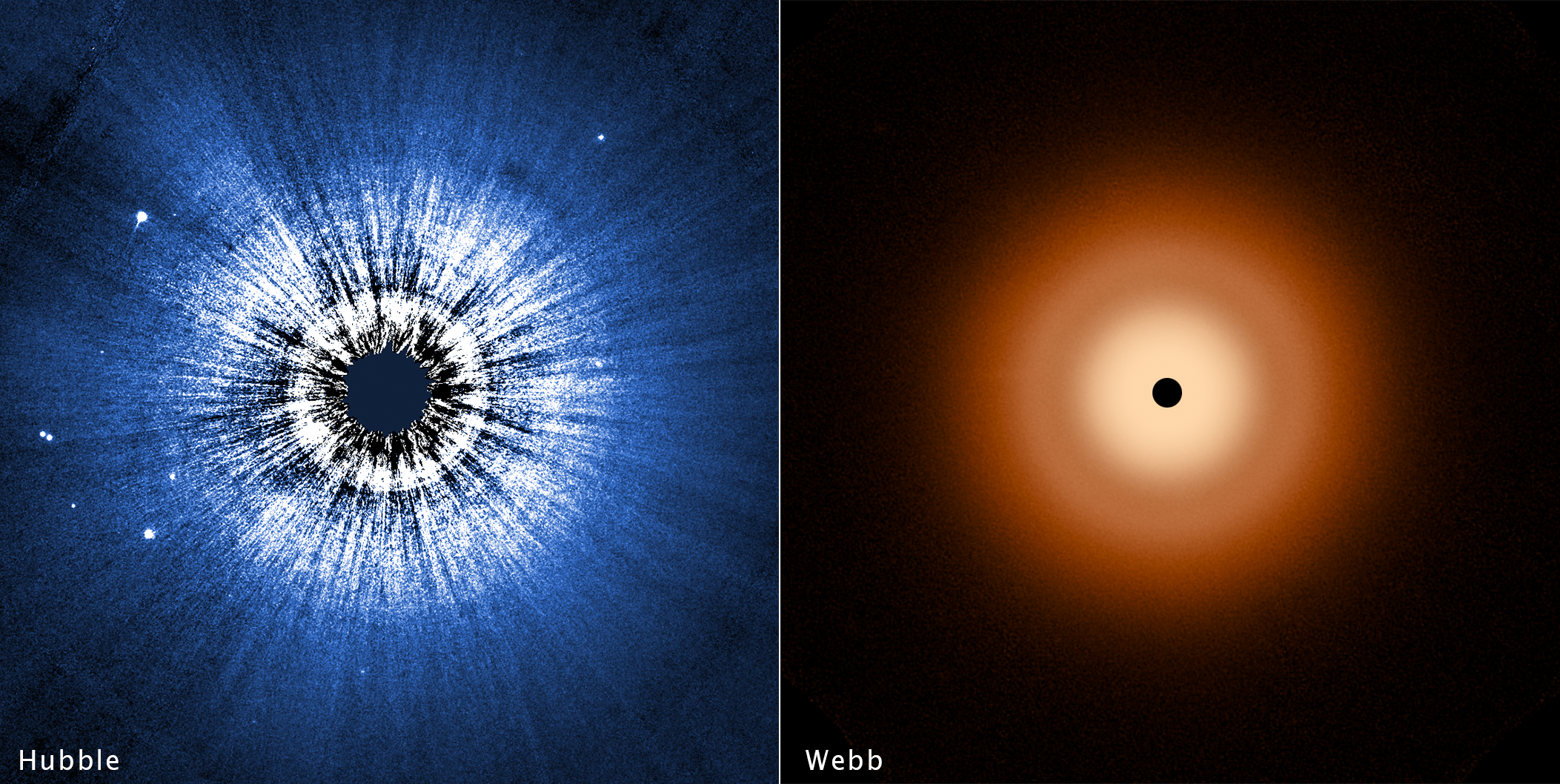

Hines learned a lot from a third of a century on the space beat, most of it enlightening but not all of it inspiring. The astronaut program was one of his particular betes noires, born of a conviction that the financial expenditure on what were really a few dozen TV spectaculars was not justified and certainly the death toll of 17 highly trained and motivated men and women could not be shrugged off as part of the cost of doing business. In the end, he fell in line behind Dr. James Van Allen, discoverer of the radiation belt that bears his name, who said on the day of the Columbia disaster of February 2003…”It’s very hard to justify the manned program. We can do much better at far less cost and at no risk to human life… I follow [manned space flights] with great interest, but that’s an entirely different consideration than whether they make any sense from a pragmatic point of view.”

Hines’ and Van Allen’s shared assessment of the value of human spaceflight is only one point where the two men’s lives touch. In the updated preface to his classic book, “The Origins of Magnetospheric Physics” Van Allen says, “The term radiation belt for a population of geomagnetically trapped energetic particles originated from a question by science reporter William Hines and my response at a May 1, 1958 conference…” At that press conference, following the successful flight of Explorer I, Hines had listened to the lengthy scientifically correct description of the new discovery of radiation trapped around the Earth and asked, “Do you mean like a belt?” The term immediately was picked up by the media and sped public understanding of the phenomena. But then, that’s what good reporters, and scientists alike, do.