Science in Space January 2024

Crew members on the International Space Station have a lot of company – millions of bacteria and other microbes. The human body contains 10 times more microbes than human cells, and bacteria and fungi grow in and on just about everything around us on Earth.

Most bacteria are harmless, and many are beneficial or even essential to human functioning and well-being. But microgravity can make some microbes more likely to cause disease and bacteria and fungi may affect the function of spacecraft systems, by, for example, corroding metal. These organisms also could contaminate other planetary bodies that spacecraft and humans land on.

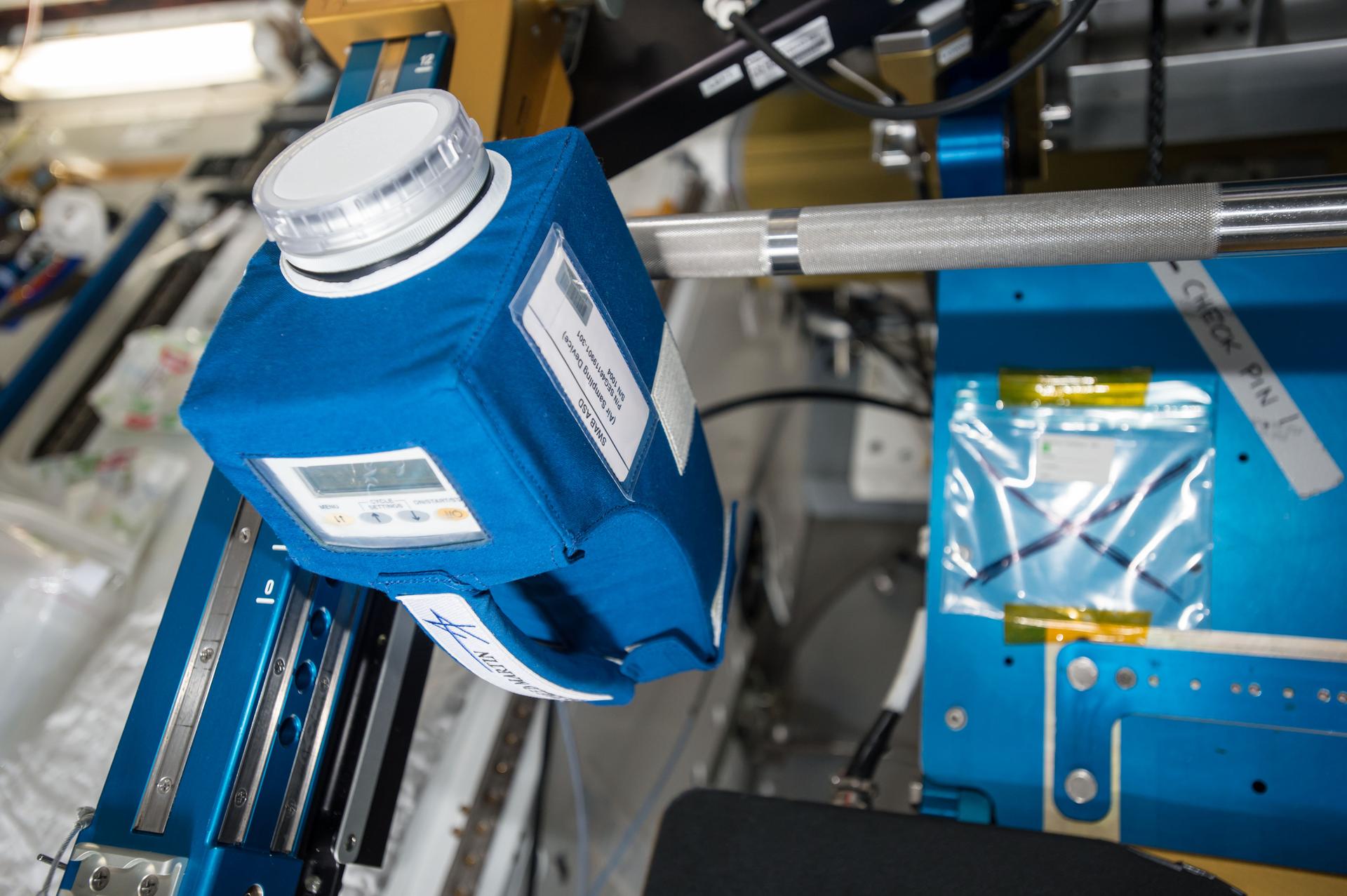

Some microbes inevitably come along for the ride on crew members and cargo traveling to the space station, and it is important to identify and control those that may be harmful – especially in a closed environment like a spacecraft. Multiple investigations have tracked, identified, and analyzed the station’s tiniest residents to help keep crew members and equipment – and even other planets – safe from any potential threats.

A current investigation, ISS Boeing Antimicrobial Coating, tests surface coatings designed to inhibit the growth of microbes to protect crew members and equipment on a spacecraft. On Earth, such coatings could help reduce diseases transmitted from touching surfaces in aircraft cabins, health care facilities, public transportation, and other settings.

Microbial Observatory-1 was one of the first investigations to monitor the types of microbes present on the space station. Researchers produced the genomes of multiple microorganisms, including some that may act as pathogens and cause disease. Published results include a comprehensive catalog of bacteria and fungi1 deposited into the NASA GeneLab system.

The Microbial Tracking-2 investigation continued a series monitoring the types of microbes on the space station and attempted to catalog and characterize any with disease-causing potential. Researchers produced whole-genome sequences of 94 fungal strains2 and 96 bacterial strains of 14 species3. The data also revealed that Staphylococcus and Malassezia species were the most common bacteria and fungi, respectively, on the space station and that, overall, microorganisms associated with the human skin dominated the surface microbiome4.

BioRisk-MSV, a long-running Roscosmos investigation, examined physical and genetic changes in bacteria and fungi on interior and exterior surfaces of the space station. Researchers found that microorganisms not only survive in this extreme environment but retain their reproductive ability as well. Most microorganisms also exhibited increased biochemical activity and resistance to antibiotics5. These findings have implications for developing planetary quarantine methods and biomedical safety systems for future missions.

The TEST investigation from Roscomos examined samples from the exterior surface of the space station and in life support systems. This work demonstrated that it was possible to collect data on viable microorganisms from open space and identified specific non-spore-forming bacteria found there6. Researchers also found land and marine bacteria in cosmic dust samples collected during a spacewalk. These microbes may transfer from the upper atmosphere via the global electric circuit (a continuous movement of electric charge carriers such as ions) or they may have originated in space7.

NASA’s ISS External Microorganisms plans to continue this work, collecting samples near life support system vents outside the station to examine whether the spacecraft releases microorganisms and, if so, how many and how far they may travel.

Myco, an investigation from JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency), evaluated whether fungi inhaled by crew members or that adhere to their skin can act as allergens. The data revealed an increased relative abundance of a common fungus associated with seborrheic dermatitis (an itchy skin rash), and the presence of several types of fungi not common on the skin8. Results also showed an abundance of a yeast that may have adhered to the skin of some crew members preflight, suggesting that a specific or uncommon microorganism can proliferate in a closed environment. This study was the first to reveal changes over time in the skin fungal microbiota of astronauts9.

JAXA also conducted a series of experiments, Microbe-I, Microbe-III, and Microbe-IV, monitoring the abundance and diversity of fungi and bacteria in Kibo, the station’s Japanese Experiment module. This work resulted in multiple publications reporting on the type and numbers of microorganisms detected10,11.

ISS Internal Environments provided a baseline of the contaminants on the space station. These data provide insight into the microbes present from the initial stages of construction through ongoing habitation of the orbiting lab.

This and other research on the microorganisms in and around the space station are helping to ensure that crew members remain in safe company on current and future missions.

John Love, ISS Research Planning Integration Scientist

Expedition 70

Citations:

1 Checinska Sielaff A, Urbaniak C, Mohan GB, Stepanov VG, Tran Q, Wood JM, Minich J, McDonald D, Mayer T, Knight R, Karouia F, Fox GE, Venkateswaran KJ. Characterization of the total and viable bacterial and fungal communities associated with the International Space Station surfaces. Microbiome. 2019 April 8; 7(1): 50. DOI: 10.1186/s40168-019-0666-x.

2 Simpson AC, Urbaniak C, Bateh JR, Singh NK, Wood JM, Debieu M, O’Hara NB, Houbraken J, Mason CE, Venkateswaran KJ. Draft genome sequences of fungi isolated from the International Space Station during the Microbial Tracking-2 experiment. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2021 September 16; 10(37): e00751-21. DOI: 10.1128/MRA.00751-21.

3 Simpson AC, Urbaniak C, Singh NK, Wood JM, Debieu M, O’Hara NB, Mason CE, Venkateswaran KJ. Draft genome sequences of various bacterial phyla isolated from the International Space Station. Microbiology Resource Announcements. 2021 April 29; 10(17): e00214-21. DOI: 10.1128/MRA.00214-21.

4 Urbaniak C, Morrison MD, Thissen J, Karouia F, Smith DJ, Mehta SK, Jaing C, Venkateswaran KJ. Microbial Tracking-2, a metagenomics analysis of bacteria and fungi onboard the International Space Station. Microbiome. 2022 June 29; 10(1): 100. DOI: 10.1186/s40168-022-01293-0.

5 Sychev VN, Novikova ND, Poddubko SV, Deshevaya EA, Orlov OI. The biological threat: The threat of planetary quarantine failure as a result of outer space exploration by humans. Doklady Biological Sciences. 2020 January; 490(1): 28-30. DOI: 10.1134/S0012496620010093.PMID: 32342323. Russian Text © The Author(s), 2020, published in Doklady Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk. Nauki o Zhizni, 2020, Vol. 490, pp. 105–108.

6 Deshevaya EA, Shubralova EV, Fialkina SV, Guridov AA, Novikova ND, Tsygankov OS, lianko PS, Orlov OI, Morzunov SP, Rizvanov AA, Nikolaeva IV. Microbiological investigation of the space dust collected from the external surfaces of the International Space Station. BioNanoScience. 2020 March 1; 10(1): 81-88. DOI: 10.1007/s12668-019-00712-1.

7 Grebennikova TV, Syroeshkin AV, Shubralova EV, Eliseeva OV, Kostina LV, Kulikova NY, Latyshev OE, Morozova MA, Yuzhakov AG, Zlatskiy IA, Chichaeva MA, Tsygankov OS. The DNA of bacteria of the world ocean and the Earth in cosmic dust at the International Space Station. The Scientific World Journal. 2018 20187360147. DOI: 10.1155/2018/7360147.

8 Sugita T, Yamazaki TQ, Cho O, Furukawa S, Mukai C. The skin mycobiome of an astronaut during a 1-year stay on the International Space Station. Medical Mycology. 2021 January; 59(1): 106-109. DOI: 10.1093/mmy/myaa067.PMID: 32838424.

9 Sugita T, Yamazaki TQ, Makimura K, Cho O, Yamada S, Ohshima H, Mukai C. Comprehensive analysis of the skin fungal microbiota of astronauts during a half-year stay at the International Space Station. Medical Mycology. 2016 March; 54(3): 232-239. DOI: 10.1093/mmy/myv121.

10 Yamaguchi N, Ichijo T, Nasu M. Bacterial monitoring in the International Space Station-“Kibo” based on rRNA gene sequence. Transactions of the Japan Society for Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Aerospace Technology Japan. 2016 14(ists30): Pp_1-Pp_4. DOI: 10.2322/tastj.14.Pp_1. 11 Satoh K, Alshahni MM, Umeda Y, Komori A, Tamura T, Nishiyama Y, Yamazaki TQ, Makimura K. Seven years of progress in determining fungal diversity and characterization of fungi isolated from the Japanese Experiment Module KIBO, International Space Station. Microbiology and Immunology. 2021 November; 65(11): 463-471. DOI: 10.1111/1348-0421.12931.