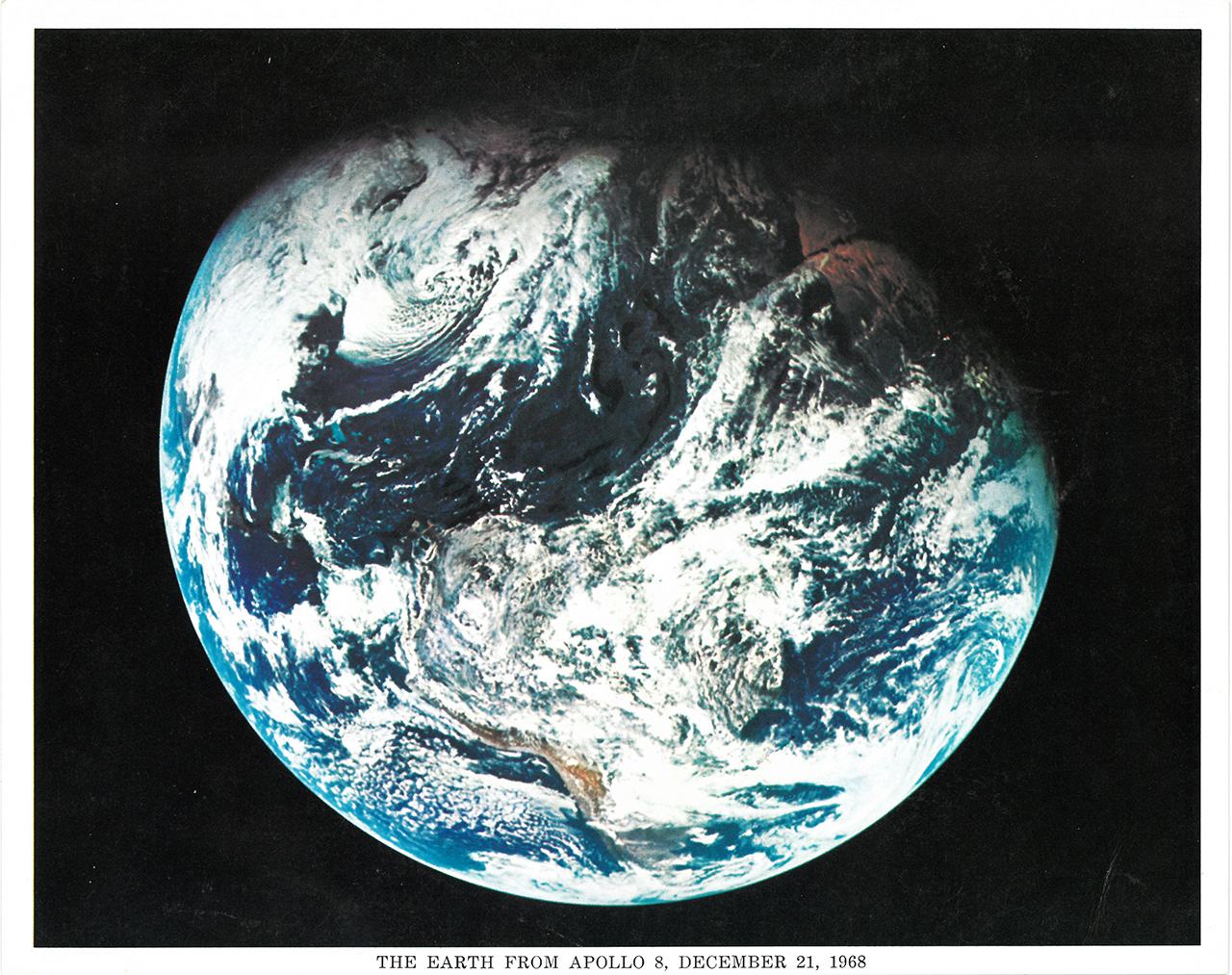

Halfway to the Moon, on Sunday, Dec. 22, 1968, the Apollo 8 crew glimpsed Earth outside their windows from a never-before-seen vantage point, slowly decreasing in size as they cut away through the deep black. “It’s a beautiful, beautiful view,” Frank Borman said to Mission Control as the spacecraft sped onward toward its destination. (MP3, NASA audio courtesy Kipp Teague).

Though some may romanticize the revolutionary 1960s, they were troubled times. Amidst this atmosphere — and surely not immune to the country’s troubling overtones — NASA engineers focused their collective efforts on responding to John F. Kennedy’s call to send Americans to the Moon and return them safely to Earth by the close of the decade.

Part 2: In the Beginning There Was Liftoff

Part 1: To the Moon and Back

69 hours, 8 minutes and 16 seconds after launch, the crew reached the far side of the Moon. They burned their engines for a lunar orbit insertion (LOI), which lasted four minutes. The burn slowed the spacecraft down so it could be captured by the Moon’s gravitational pull, making it the first ever manned satellite of another world. Listen to the pre-burn communications with NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston on Monday, Dec. 23: MP3, NASA audio courtesy Kipp Teague.

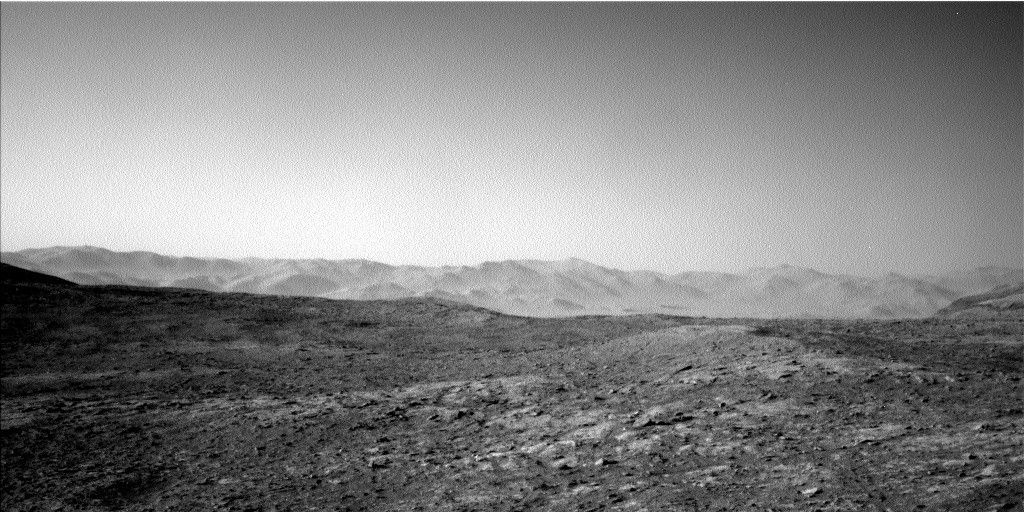

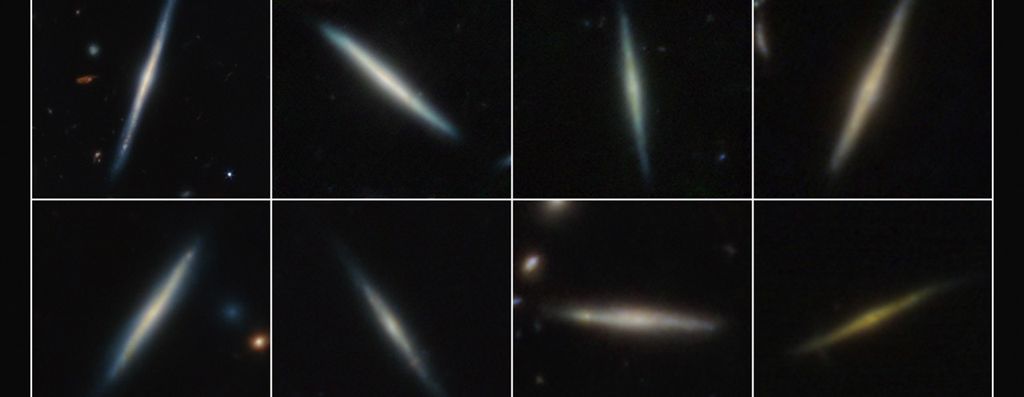

The Moon is tidally locked to Earth, which means it rotates on its axis at the exact same rate that it orbits Earth. As a result, we only see one side of the Moon from Earth’s surface. Borman, Lovell and Anders were about to get the first naked-eye glimpse in history of the other side. Rocky, barren, and marred with craters of all shapes and sizes, Lovell described it during a live telecast as, “essentially gray, no color…like Plaster of Paris or some sort of grayish beach sand.”

That grayish beach sand passed rapidly outside the spacecraft windows, 96.6 kilometers (60 miles) below as the crew carried out a variety of tasks. These included capturing dozens of photos and conducting six live telecasts, two of them broadcast from lunar orbit in real-time to five different continents and watched by more people than any other television program at the time.

International television broadcasting was a relatively new concept, and spaceships only a very modern reality — the Wright brothers flew for the first time just 65 years prior. NASA had only existed for 10, and within that decade, an outpouring of national pride and ambition had mobilized a government agency to not only get three men to the Moon, but to broadcast it live. Such a feat was not lost on the world, nor on the astronauts themselves. On Christmas Eve, 1968, Borman, Lovell and Anders filmed the surface of the Moon from Apollo 8 and commemorated their moment of awe, each man taking his turn to read from the book of Genesis (MP3, NASA audio courtesy Kipp Teague).

The Christmas Eve broadcast ended an apprehensive year on a hopeful note, bringing to the world a reminder of the all-encompassing curiosity stitched into the fabric of the human race — our primordial need to stretch out our arms, to see what is over the next hill. Both the crew on board and the mission’s orchestrators on the ground expected stunning views of the Moon, but over that proverbial hill, they were graced with a sight unexpectedly beautiful: Earth, our tiny blue marble, our one-and-only home.

Jim Lovell said of the view:

“The vastness up here of the Moon is awe inspiring. It makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the blackness of space.” (MP3, NASA audio courtesy Kipp Teague).

As Earth rose over the lunar horizon, Anders immortalized his view of the moment in an image now known as “Earthrise.”

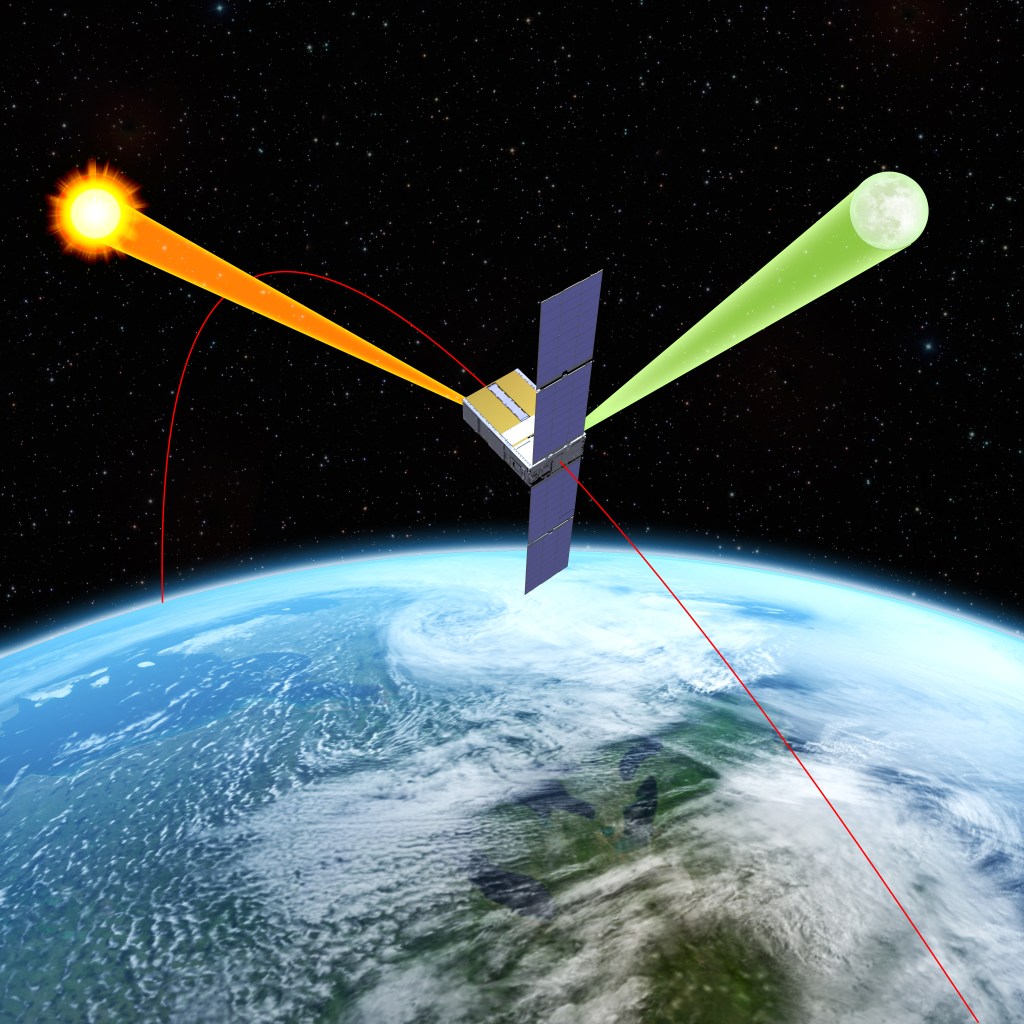

Using photo mosaics and elevation data from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), this video commemorates Apollo 8’s historic flight by recreating the moment when the crew first saw and photographed the Earth rising from behind the Moon. Narrator Andrew Chaikin, author of “A Man on the Moon,” sets the scene for a three-minute visualization of the view from both inside and outside the spacecraft accompanied by the onboard audio of the astronauts. Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center