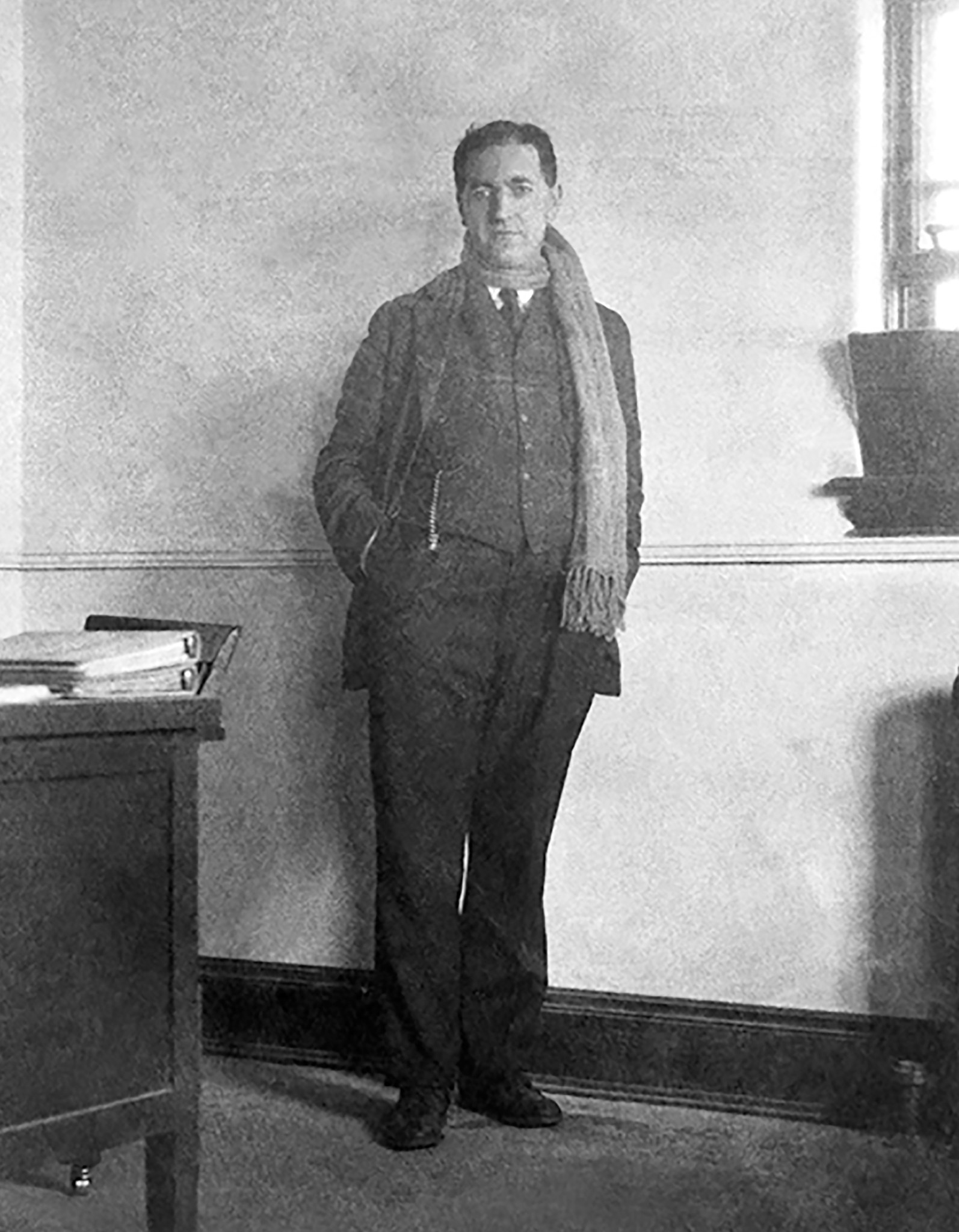

Dr. Max M. Munk (1890 – 1986) achieved lasting fame by conceiving, developing, and placing into operation the Langley Variable Density Tunnel. This achievement was the most significant accomplishment of the embryonic NACA, and placed the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory (LMAL) at the forefront of the world’s aeronautical leaders. Dr. Munk only spent six years with the Committee, but he did more to shape the history of the NACA than any other researcher in a comparable period of time.

Munk was born in Hamburg, Germany. He earned an engineering degree at the Hanover Polytechnic School in 1914, and doctorates in physics and engineering from the University of Gottingen in 1917. Because of their world-wide reputations as leaders in aeronautical sciences, Munk and other Europeans became targets of the managers of the new NACA. He was a well-known protégé of Ludwig Prandtl, the noted German aerodynamicist. NACA management anticipated that Munk’s abilities as a theoretician and generalist would allow him to augment the work of experimental engineers at the new LMAL. President Woodrow Wilson signed orders allowing Munk to come to the United States and work in government, required because Munk had been a former enemy. (This same process was followed again after World War II, to bring Wernher von Braun and his rocket team to the U.S.) In 1920, he left his native Germany and became a technical advisor to the NACA at its headquarters in Washington, D.C., working on theoretical problems.

While in Washington, in 1921 Munk made his proposal for what would become one of the most revolutionary facilities ever constructed by the NACA. At that time, the fledging Langley laboratory operated only one wind tunnel — a simple atmospheric tunnel based on a European design that was essentially obsolete. It was used for training the young, inexperienced staff in the process of wind-tunnel testing more than as a research device. One of the major issues facing users of atmospheric tunnels was a well-known, potential impact of the aerodynamic parameter known as “Reynolds number” on test results. Significant differences were known to exist between results obtained in wind tunnels compared to flight data for certain critical parameters, such as the magnitude of maximum lift used to lower landing approach speeds.

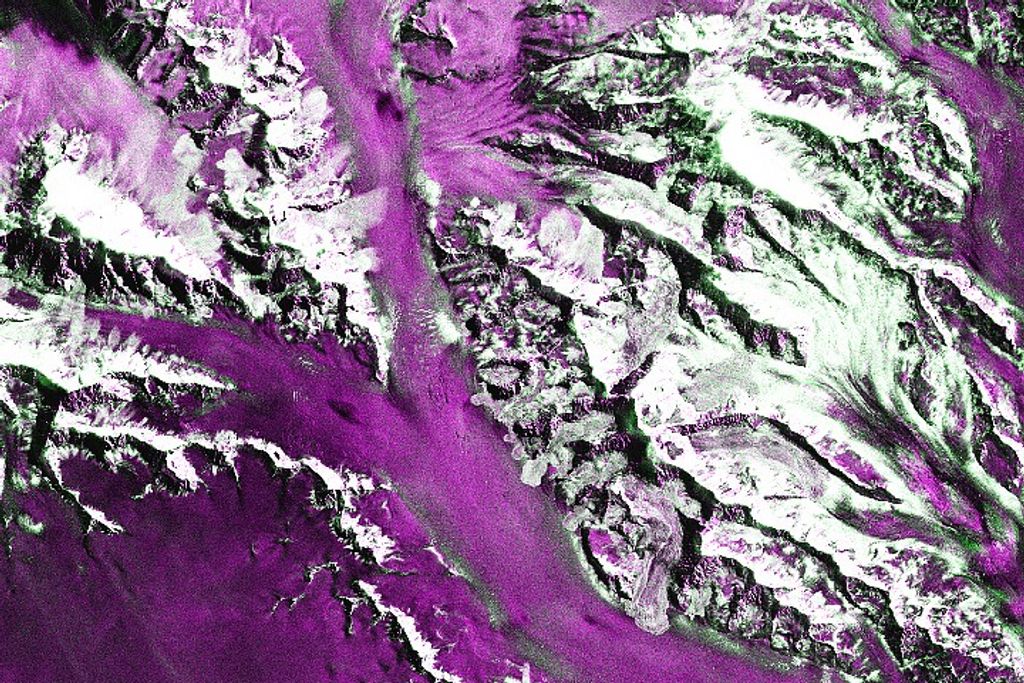

Munk proposed a wind tunnel in which the Reynolds number conditions in the tunnel were directly comparable to those in flight. The key to his remarkable concept was air density. By increasing the pressure in the wind-tunnel test section (and, therefore, the air density), flight conditions could be replicated. Although this concept was known prior to Munk’s proposal, no one in the world had used it. Munk’s idea became the Langley Variable Density Tunnel (VDT), essentially a wind tunnel in a steel tank that could be pressurized. When the VDT went into operation in 1922, and produced remarkable results, it was regarded as revolutionary; and although other nations quickly began building pressurized tunnels, the NACA would lead the world in this area for over a decade. The success of the project and its value to the world of aeronautics was underlined by additional funding for the NACA from Congress, which was deeply impressed by the new facility.

In addition to his landmark contribution of the VDT, Munk revolutionized airfoil theory. His doctoral thesis, developed under the tutelage of Ludwig Prandtl, had been on parametric studies of airfoils, discussing the genesis of what would become airfoil theory. He became best known for his development of thin-airfoil theory, a means of modelling the aerodynamic characteristics of airfoils by separating their shape factors, such as thickness and camber. Introduced in 1922, his theory remained the primary theoretical technique applied to the design of airfoils, until the development of laminar flow airfoils by Langley’s Eastman Jacobs in the 1930s. From this work flowed the achievement for which the NACA is perhaps best known among aircraft designers — the NACA family of airfoil shapes.

Munk was stationed with the NACA in Washington for six years; but, in 1926, following his brilliant success in initiating airfoil research in the VDT, Munk was transferred to the LMAL as Chief of the Aerodynamics Division, making him second-in-charge at Langley. The position included responsibility for all wind-tunnel, flight-research, and analytic research conducted at the lab. Munk was extremely successful in his research efforts. In his years with the NACA, he authored or co-authored 57 reports.

However popular he may have been with NACA management in Washington, he was not well liked at Langley. The brilliant theoretician had become a serious problem, regarded as arrogant and eccentric by many of the Langley employees; and he was forever at the center of controversies characterized by extremely strong opinions on all sides. The situation quickly degenerated into battles between the celebrated scientist and the renowned engineers that attempted to work with him.

Langley’s future Director, Floyd Thompson, recalled sitting in one of many heated debates between Munk and the legendary researcher, Fred Weick. (Weick led researchers at the Langley Propeller Research Tunnel in their research on engine cowlings, for which Langley was awarded its first Collier Trophy.) According to Thompson, an argument between the two stubborn people degraded to the point where Munk said, “Mr. Weick, we should agree, so that when we get in meetings, we say ‘this is the way it should be.’ No one will dare stand against us. Therefore, we should agree on my position!” Weick left the meeting and proceeded to use his own personal position.

Munk resigned from the NACA in 1927, and subsequently held jobs with Westinghouse, the American Brown Boveri Electric Corporation, and the Alexander Airplane Company in Colorado. He also taught mechanical engineering at Catholic University. In 1945, he joined the Naval Ordinance Laboratory as a research physicist working on turbulent fluid motion. He then returned to Catholic University and retired in 1961. He donated his entire collection of papers to the Langley Historical Archives.

Dr. Max M. Munk died on June 3, 1986, in Ocean City, Maryland, at the age of 95.