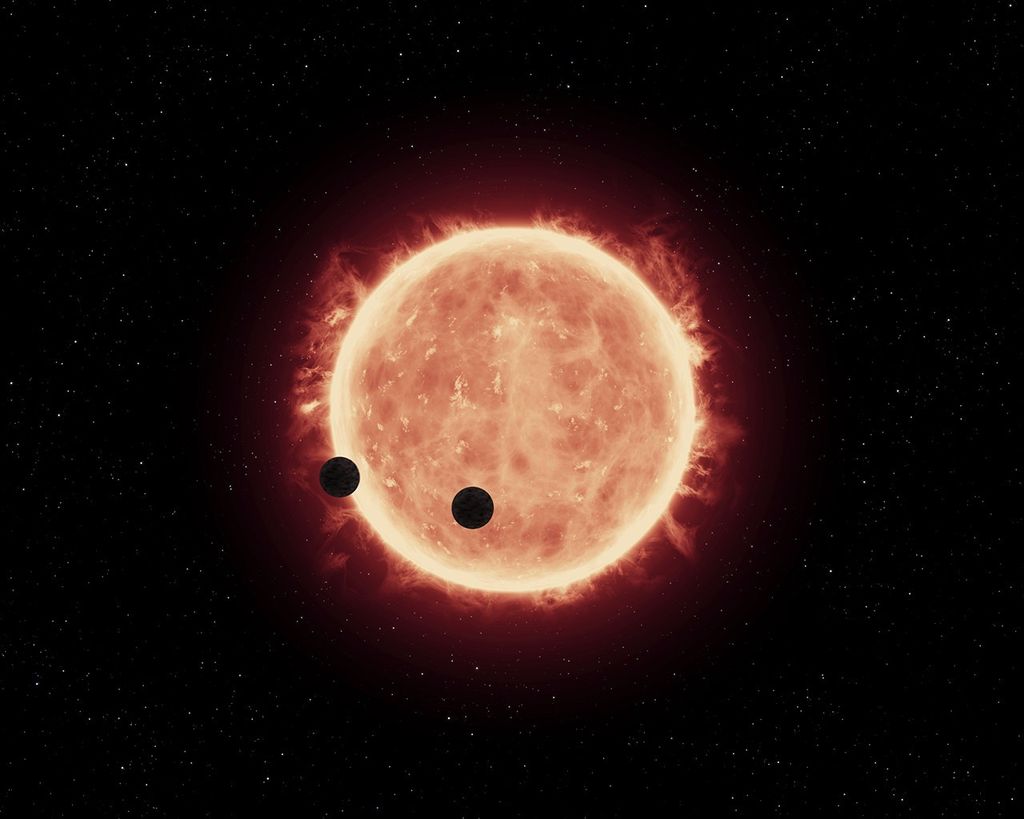

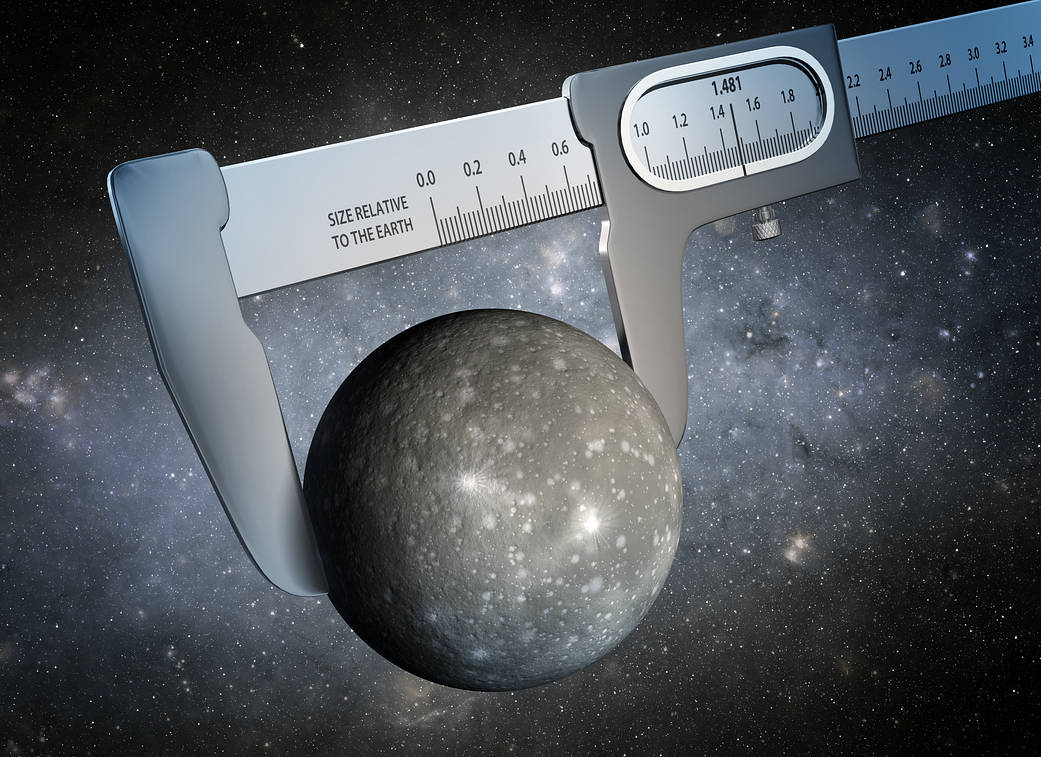

Using data from NASA’s Kepler and Spitzer Space Telescopes, scientists have made the most precise measurement ever of the size of a world outside our solar system, as illustrated in this artist’s conception. The diameter of the exoplanet, dubbed Kepler-93b, is now known with an uncertainty of just one percent.

According to this new study, the diameter of Kepler-93b is about 11,700 miles (18,800 kilometers), plus or minus 150 miles (240 kilometers) — the approximate distance between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, Penn. Kepler-93b is 1.481 times the width of Earth, the diameter of which is 7,918 miles (12,742 kilometers).

The results confirm that the exoplanet is a “super-Earth.” Although super-Earths are common in the galaxy, none exist in our solar system. Exoplanets like Kepler-93b are therefore our only laboratories to study this major class of planet.

With good limits on super-Earths’ sizes as well as their masses, scientists can now start to theorize about what makes up these weird worlds. Previous measurements, by the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, had put Kepler-93b’s mass at about 3.8 times that of Earth. The density of Kepler-93b, derived from its mass and newly obtained radius, indicates the planet is in fact very likely made of iron and rock, like Earth.

Despite its newfound similarities in composition to Earth, Kepler-93b is far too hot for life. The exoplanet’s orbital distance — only about one-sixth that of Mercury’s from the sun — implies a scorching surface temperature around 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit (760 degrees Celsius).

The methods employed in the new study could help nail down the sizes of other exoplanets, and improve our understanding of alien worlds.

The Spitzer data for this study was obtained during the “warm mission” phase using its Infrared Array Camera. The lead author of the paper describing these findings is Sarah Ballard, a NASA Carl Sagan Fellow at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech