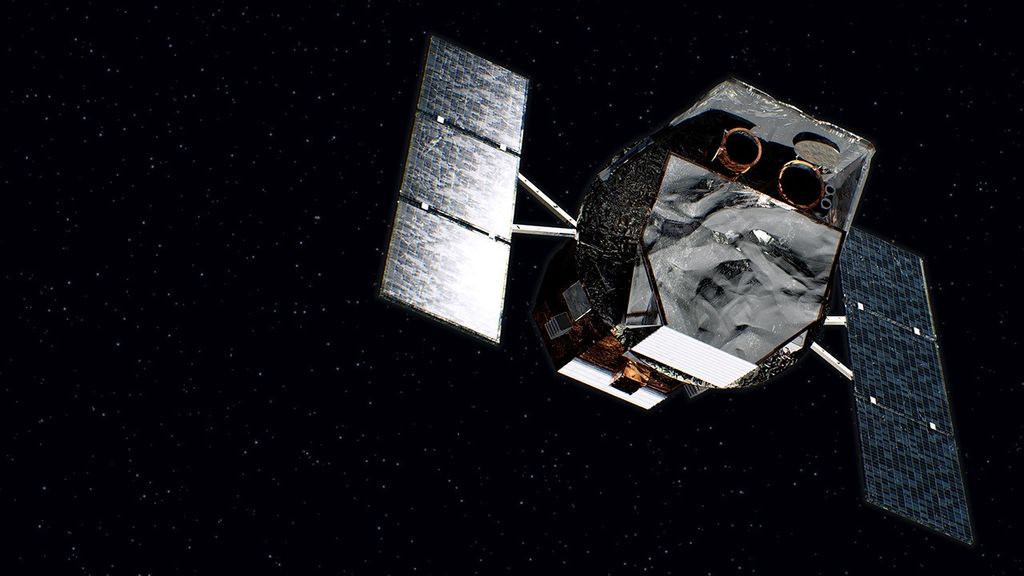

Within the swaddling dust of the Serpens Cloud Core, astronomers are studying one of the youngest collections of stars ever seen in our galaxy. This infrared image combines data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope with shorter-wavelength observations from the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), letting us peer into the clouds of dust wrapped around this stellar nursery.

At a distance of around 750 light-years, these young stars reside within the confines of the constellation Serpens, or the “Serpent.” This collection contains stars of only relatively low to moderate mass, lacking any of the massive and incredibly bright stars found in larger star-forming regions like the Orion nebula. Our sun is a star of moderate mass. Whether it formed in a low-mass stellar region like Serpens, or a high-mass stellar region like Orion, is an ongoing mystery.

The stellar “hatchlings” in the Serpens Cloud Core represent the very youngest stages of stellar development. They appear as red, orange and yellow points clustered near the center of the image. Other red features include jets of material ejected from these young stars. Some mature stars that are not in the nebula appear yellowish due to dust obscuring our view at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

This region also includes a population of prenatal stars that are so deeply enshrouded in their dusty cocoons to be completely hidden in this view. They only become detectable at much longer wavelengths of light.

The inner Serpens Cloud Core is remarkably detailed in this image, as it was assembled from 82 separate snapshots totaling a whopping 16.2 hours of Spitzer observing time. Serpens is one of several star-forming regions targeted by the Young Stellar Object Variability (YSOVAR) project, which conducted repeated observations in each area to look for changes in brightness in the baby stars. Such fluctuations can provide valuable clues to how stars gobble up gas and dust as they grow and mature.

Spitzer observations at wavelengths of 3.5 and 4.6 microns are shown in green and red, respectively. 2MASS data at 1.3 microns is displayed as blue. These observations date from Spitzer’s warm mission phase, following the depletion of its liquid coolant in 2009.

The 2MASS mission was a joint effort between the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif., the University of Massachusetts and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., manages the Spitzer Space Telescope mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Science operations are conducted at the Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Spacecraft operations are based at Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company, Littleton, Colorado. Data are archived at the Infrared Science Archive housed at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at Caltech. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/2MASS