“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

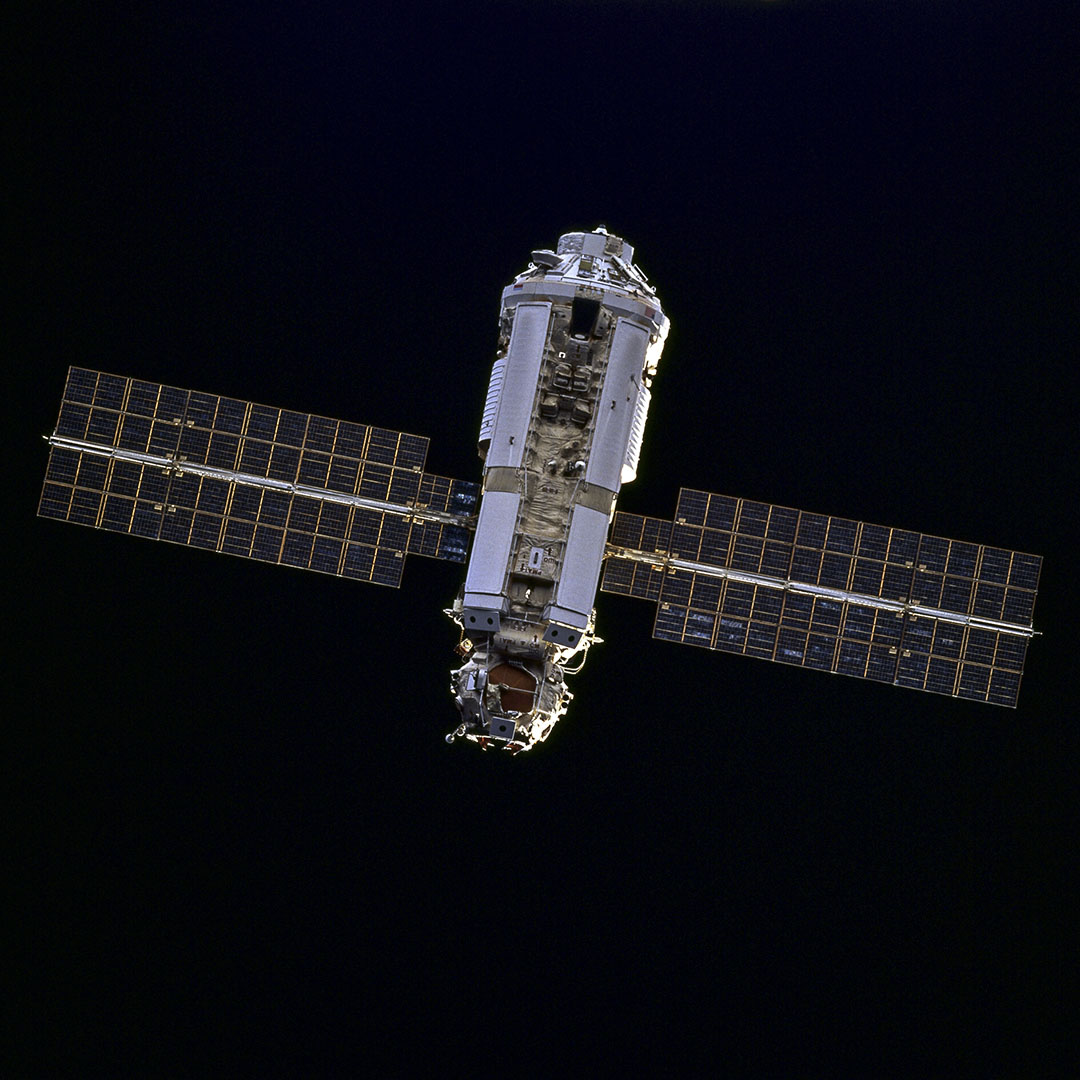

Doug Drewry, former FGB Program Manager, discusses leading the joint U.S and Russian teams during the development and launch of Zarya, the first element of the International Space Station, for its 20th anniversary in space. This episode was recorded on October 9, 2018.

Check out the Space Station Assembly Page to see information on assembly of the space station starting with Zarya.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnston Space Center, Episode 72, The International Space Station Begins, Part 1. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know the coolest information about what’s going on here at NASA. So, 20 years ago, on November 20, 1998, the first element of the International Space Station called Zarya was launched to space. It was the first step towards two decades of international cooperation, scientific research, and discovery. We’re sort of used to talking about the International Space Station now. Crews come and go on long duration journeys, and during each journey, the astronauts are conducting hundreds of experiments, doing space walks, and making it all look relatively routine. But, of course, to get to this point, you had to start somewhere, and that was with Zarya, the first element of the space station. Designed, constructed, and flown as a joint effort between Russia and NASA. It was a critical step and a critical module to provide power, propulsion, guidance, and all the essentials that would enable the first modules to be attached and to function properly.

So, with me to tell this story of the first element is Doug Drewry, the former FGB Program Manager and launch package manager for the mission. You hear us say FGB a lot. It stands for Functional Cargo Block, but a G instead of a C since it’s translated from Russian. Doug had a variety of jobs during his 22 years at NASA, including leading the joint U.S. and Russian teams for the successful development and launch of Zarya. He’s now the president and owner of his own aviation company. So, with no further delay, let’s jump right ahead to our talk with Doug Drewry to tell the story of our first steps in this, the 20th anniversary of the International Space Station. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Doug, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today to celebrate 20 years of the International Space Station.

Doug Drewry: Thanks for having me.

Host: All right. We’re going to take it all the way back and even beyond that, I think, because 20 years ago was the actual launch of Zarya. But, it started even before that, and it started even before it was Zarya. So, sort of set the scene. Before this even came into place, what was happening at NASA? Where were we?

Doug Drewry: Well, we started the space station back, way back with space station Alpha. That evolved into space station Freedom. We went through several redesigns of space station Freedom. There was a major redesign a few years before we started talking to the Russians. It was called preintegrated truss redesign where I ended up leading the MB3 and MBA which was the S1 and P1 segments that are on orbit today. It’s the preintegrated truss. And then, we went up to our critical design review on that when there was another station redesign. We were, at the time, we were divided into work packages. JSC was work package two. I don’t remember which, who had all the other work packages, but you had power being done out of one place and all these various things. So, anyway, we were told to redesign, and with a new inclination, we were supposed to go to 51.6 degrees of inclination which we knew is where the Russians were flying. But, of course, every time we queried that, it was denied that anything to do with it. It was just supposed to be another redesign of the station which we’d been through so many times before for budget cuts and this and that.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: JSC did an option C which was a single launched orbit, and SLC option which was basically modifying a shuttle external tank and fitting it out with the various levels. Marshall took basically the Freedom design, much like the current space station, and instead of backing the work package two days where we were launching outboard in, we were launching solar rays first and propulsion modules so we would have command control on orbit. And, we kind of built up to the point where we built the truss first and then added the pressurized modules and brought in crew. Marshall took the approach of bringing out the modules first and then building outward on the truss to power them.

Host: So, several different, I mean, this is a very dynamic time with the, this idea of a space station is there, but, what, you know, how do we make this a possibility. And, everyone’s redesigning it, trying to come up with the right strategy. You’re going through design reviews but don’t even know what the space station is going to look like at this point. But, you understand that maybe there’s some collaboration coming down the road.

Doug Drewry: Well, space station Freedom was really pretty far along, and it’s, I mean, we were cutting metal and building hardware already.

Host: Oh, okay.

Doug Drewry: And, it’s largely the U.S. segment that’s on orbit today. It’s just the approach for putting it together was radically different. Again, one of the politically expedient things was to get crew on orbit as soon as possible. And, under the Freedom program, we were a few years into the building segments out before we brought crew on board. So, at shuttle flights, we would leave it on orbit for a period of time. And so, there was a real effort to change that. The last redesign that threw in the 51.6 inclination really hurt us performance wise. That took about 30% of the shuttle’s carrying capability out to go to that higher inclination orbit.

Host: Oh, really?

Doug Drewry: So, that was a big impact on. We couldn’t just fly the preintegrated truss segments like in the modules like we had planned with Freedom because the shuttle didn’t have the carrying capability now at the higher inclination. So, one of the things Marshall did on their option, they were option A, I believe, is they offloaded racks and things in the modules. We did different things to the truss to try to lighten it up and be able to carry it up to that higher inclination. So, bottom line is Marshall was announced as the winner of the competition that we were going to build space station Alpha, I think it was. That was the other one it was called at first. And in the meantime, there were a few of us pulled off to the side and said, “Well, let’s see if we can integrate the Russians into this.”

Host: Hmm.

Doug Drewry: And, we went through weeks and weeks of meetings in Crystal City to meet with Russian counterparts and mostly people from RSA at the time. Although, honestly, I was involved in a lot of those meetings and Khrunichev representatives were there. And, I don’t remember them ever being introduced as being anything other than with the Russian contingent that they were part with RSA or Energia.

Host: Oh.

Doug Drewry: So, the bottom line is we came up with a viable assembly sequence, had the service module as the first element. And, the node was several elements down before we could get it up. Because, again, we had that problem. You have to, once you put something on orbit, you have to be able to drive it around the sky. So, you have to have propulsion. You have to have command and control. You have to have an ability to keep it up there, re-boost if necessary. So, we’ve, at some point, formally adapted, or adopted that we were going to be working with the Russians.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, interestingly, in, it was October of ’93, I got a phone call on a, I believe it was on a Thursday about noon said go over to building x and get your picture taken, you’re flying to Russia tomorrow. And, I met several other people from here that were in the same boat. We were all getting out picture taken. They explained to us that our passports would be meeting us, we’d be stopping D.C. on the way over, and they’d meet us there with our passports and our VISAs. And, mine was one of two that didn’t make into D.C., so I spent an extra night in D.C. I flew into Moscow the next day, and we spent, I want to say we spent about a week meeting with the Russians again. Dave Mobley from Marshall led that team. There was probably, I don’t remember the number. Close to 20 of us, 18 to 20 of us that went over there.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: And, this was, this was right about the time they were, the Russian tanks had fired on the White House in Moscow. So.

Host: Politically, it was.

Doug Drewry: It was an interesting time to be there.

Host: Interesting time, yeah.

Doug Drewry: I remember my first impressions of flying into Moscow was it was all black and white. Except for the red stars and red pictures of Lenin on the sides of every building and statues everywhere.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: And, as a contrast to when we left, I tell everybody it was in pastels. It was a totally different place than when we first flew in. But.

Host: Wow. And, why the speed? Why were you, why’d you have to go so fast?

Doug Drewry: We were sent over, the direction we were given was that call it a semiofficial however you want to couch that. But, we were told we needed to go, come up with a, we, the Soviet Union has, was breaking up. They needed money desperately. Our White House had decided that we were going to give them money to keep them from selling nuclear weapons to other people to raise cash.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, NASA was one of the mechanisms to do that. So, we were sent over specifically with the directive that the first module had to be a U.S. module, and the U.S. astronauts had to be onboard before Russian astronauts.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, so we went over, and we tried, oh, for a good week to try to manipulate the sequence to make that happen, and there’s just no way because, again, we needed that command and control function up front. And, meekly, out of the back of the room, this gentleman stands up and said, “Well, we could do that with an FGB.” And, we broke into that discussion for the next rest of the day, and it turned out it was Khrunichev suggesting what became the FGB. It was based on one of their, one of their military vehicles that they’ve built, they’ve used for many years, I guess.

Host: So, FGB did not originally mean Functional Cargo Block.

Doug Drewry: No, it was always Functional Cargo Block.

Host: Oh, I see.

Doug Drewry: But, that’s different than the FGB that we’re applying on orbit.

Host: Okay. Okay.

Doug Drewry: Yeah. Quite interestingly, and we thought we had agreement, and we came in the next morning, and Energia and RSA told us that wasn’t going to work. And, we threatened to walk out after half a day and leave Moscow. And, they finally agreed to meet with us again, and that afternoon, the administrator and Bill Shepherd who is the program manager at the time for space station, he flew over with George Abbey and we met with them in the afternoon, told them what was going on, and he next day, we briefed the concept with the FGB to Goldin and Koptev.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: Which was the head of the Russian Space Agency.

Host: So, this was definitely not a straightforward process.

Doug Drewry: Oh, no. It was— [laughter] In fact, when, interestingly, when we were actually doing the briefing to Koptev and Goldin the next day, the Russians, again, objected. In Russian this time. And Koptev called an end to the meeting and sent all the Americans out of the room and called us back in about 30 minutes later and said we could get on with the meeting now. And, what he explained to us is that RSA had objected. One of the things they said was that, you know, the FGB, some of the systems were built in the Ukraine, and you know how those Ukrainians are. And, Koptev proceeded to tell us that the Ukrainians built the systems for the Energia modules as well, and so, it was really a nonargument. It was just another attempt to keep Khrunichev out of the loop, I think. And, bottom line is we left Moscow with an agreement, with an assembly sequence, and it had the FGB. It was the best we could do is the FGB was the first element. The node was the second element. So, we would get a U.S. module up before the service module. Our direction had been a U.S. lab before the Russian lab, but we, the node was the best we could do because, again, we needed some power.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, basically, we flew up 2A with the node as the second flight, and then it was almost a year before the service module would come up as the third flight.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: So.

Host: Yeah, it was just the two for a while, but.

Doug Drewry: Yeah. Yeah, we drove it around for about a year. That’s where we had to put a lot of requirements on the FGB. Basically, the FGB is the keystone of the space station. It’s the thing that holds the Russian segment and the U.S. segment together. It’s got all the fluid power, A/C, all the interfaces go through that module and had to be built into that module.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: It’s bigger than the Russian original core module was. It’s got a different power system. We had to run on 120 volt power to be compatible with the U.S. stuff. We put that docking ball in the front which is bigger than anything the Russians had ever done. Which, in we had to build, build in an APAS or a docking system to dock with the shuttle because 2A was going to come up and dock to that, and we wanted to be able to do that. We had to make the solar arrays retractable. We’ve got U.S. computers in the module, MDMs and things. So, it’s radically different than anything the Russians had done before.

Host: Was this kind of decided after all the meetings and, or was it—?

Doug Drewry: Yeah. At that meeting in Moscow, we came up with this sequence.

Host: Sure.

Doug Drewry: And then, we actually left that meeting with the FGB was going to be a Russian contribution to the space station. And, they were supplying it. Sometime, I believe, in November, they came over, this would be November ’93. And, we agreed to pay I think it was $7.9 million for modifications that we needed to their hardware to the FGB to make it do some of the functions we did.

Host: And, that included the docking mechanism, the solar arrays, or were these separate?

Doug Drewry: It included some of those things. Some of them came up later. I mean, it’s just like any other design.

Host: Sure.

Doug Drewry: Viewgraph engineering. It looks good on paper, and as you actually started building, you started to run into other things.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: So, we did make a lot of modifications along the way.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: But, I had a full-time team of U.S. specialists and Russian specialists. We actually built an office in the Khrunichev plant in Moscow. Which showed up as a park on their maps. It was, Khrunichev was primarily a military supplier, I guess, you would.

Host: Oh, interesting.

Doug Drewry: And, yeah, so you couldn’t find it on a map. And, it was an interesting place to be.

Host: Wow. Yeah. So, that was kind of interesting because it didn’t just, you didn’t just start and everything was collaborative. You know, it was, it was definitely a process to get to where you needed to be, which was a module that was both a U.S. and Russian module that worked for the purpose of, like you said, holding the space station together.

Doug Drewry: Sure. Yeah. And, we, so we, it was a big collaborative effort from the beginning on we all recognized we were going to have to make modifications, and they were going to be pretty serious modifications.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: But, we were still, it was still couched as part of the Russian contribution of the station. It wasn’t until we were probably six months into the design, working with Russians on a daily basis and multiple trips there, and stuff, that all of a sudden, we got word from headquarters one day saying that the Russians had come to them saying the FGB was a solution to our political problem.

Host: Oh, boy.

Doug Drewry: That the old sequence would have worked fine, and therefore, we should be paying for it. And, Boeing took over as a prime contractor. So.

Host: Oh, okay.

Doug Drewry: But, part of that decision to, for us to fund the FGB included, I insisted that we have to have better access to the hardware. And, that’s where they ended up building an office just inside the plant wall. We had an outside entrance we could get into it without going through their security every time. And, I kept it staffed with two people, and we were in and out of there all the time and in the plant. It was such a different environment working with the Russians than what we were used to on the U.S. side. We, and, again, keep in mind this was a, was an ex-military hardware for them, or maybe current military hardware. And so, every time we wanted to see design details, we basically got to the point where I would send one or two people from our meeting there, whoever had the most direct interest. They would take them back into a vault room, pull out the original drawings, and on the U.S. side, you know, we did everything electronically.

We had drawings and everything. On the Russian side, they pulled out original hard copy prints, and you could see initials for changes through the years for the last 15 years and every time they’d made a change. So, it was really a different way of doing business from what we had seen originally.

Host: Wow. Yeah, so not only was the actual collaborating on who does what and everything, but just the different way to do things, a different process.

Doug Drewry: Oh, entirely.

Host: Yeah. That’s interesting. And, a different language to communicate through.

Doug Drewry: It was, of course we had interpreters.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: All the time. And, a lot of our people picked up Russian along the way. I think I’ve forgotten more Russian than I learned. But, yeah, it was very interesting. It was an interesting time to be over there.

Host: Okay. So, tell me about actually going over and the actual working part. So, you’re in Moscow. You’re in this park, I guess. Working on all of this, but, you know, some it, like, I think is manufactured in Ukraine. Did I get that right?

Doug Drewry: No. It was just some of the components.

Host: Components were from Ukraine.

Doug Drewry: Some of the GNC components were made there.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: You know, Russia, one of the things we ran into going over there was that, and one of the problems, frankly, I had with the contractors on the first part on our side was, in our own contracting office, was the way we do business in the U.S. is we try to figure out a fair market value for something and try to understand what the actual costs are. When we got, and one of the things when we first got to Moscow is we heard that their engineers hadn’t been paid for six months or something.

Host: Oh, wow.

Doug Drewry: That they were in such bad shape. One of the things, a couple things learned on that was that first it was virtually impossible to figure out what costs really were because the whole Russia Soviet Union things was basically a, almost a barter system where the government supplied everything. So, the government, the people in the power plants got food and supplies and things they needed, and they supplied the power to the refineries that smelted the metal. And, they got what they needed, and they supplied it to here and there. And so, basically, when we get down to the aerospace level, the people at Khrunichev or Energia or RSA really didn’t know what the materials cost and really didn’t know what labor cost. The whole thing about the Russians not being paid, I asked one of them one time on one of those early meetings. I said, “So, if you haven’t been paid for six months, why are you still here?”

And, he shrugged his shoulders and said, “What else would I do?” And, it turned out that they actually lived in company housing. Their food and supplies were supplied by the company. In this case, the company is technically the government. And that, you know, the pay that they didn’t get was their incidental, you know, their play money is kind of what it was. So, it wasn’t like they were like here you didn’t get a paycheck and you didn’t know how you were going to eat or pay your rent. That was all taken care of for them.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: And so, it was, it was really a hard thing for people on our side to understand. It took me quite a while to understand.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, one of the biggest frustrations that I had early on, and I think, unfortunately set the stage for where we are today is I would go over there with a team of people, and I’d usually bring, you know, 10 to 12 people with me when I’d travel or different technical experts, but we would sit down, and we would, over a week, negotiate a deal on something.

Host: Well, once we did, you know, come up with an agreement whether or not it was.

Doug Drewry: Right, right.

Host: The most efficient agreement, you know, we came up with an agreement, and they got what they needed to build certain hardware. You’re in Moscow. Where is everything being built? Where is everything being tested? How is it being relayed back to the U.S.?

Doug Drewry: We were, we were actually building the FGB in the Khrunichev plant there is Moscow.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: We were bringing U.S. components over there. You know, there was, when we set up the contract, one of the things that they wanted was to build a test article. They wanted to build a flight article and a test article which we had originally had back in the early days of space station. But, that’s one of the things we had scrubbed out along the way is this duplicate hardware. And, we had to come up with a different way to figure out how we were going to integrate modules since the first time they would physically see them, each other would be on orbit in a lot of cases.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: And, that’s one of the things that happened with the FGB, too. So, we were, we were doing a lot of integration work on both sides. We, I almost constantly had people in Moscow, depending on what stage of the build we were in, what was going on. The full-time representatives that I had in our FGB office there kept us informed much better than we would have otherwise. We, not many people know, I think, but the FGB that’s on orbit today was actually cut in half at one point because it actually was over tested and blew out the end of a module during a test.

Host: Really?

Doug Drewry: Yes. And, one of the ways we found out about that was we found out immediately because of our resident people there in that plant. And, it took, it was a fight to make sure we had our people involved in the resolution of the problem, and ultimately, we decided jointly with the Russians that they would cut the end of the module off and weld a new piece on, and that’s the one that’s on orbit. So you know, the team did a great job.

Host: It’s welded, and of course tested to make sure—

Doug Drewry: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah.

Host: And it’s held for this long, so.

Doug Drewry: Oh yeah, yeah, we had an original requirement to, our build life was supposed to be ten years with renewable to 15 years. And, obviously, we’re going up on, we’re coming up on 20 now.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, you know, and I don’t see any problems for going further, so.

Host: So, how was the, how are the teams in Moscow rotated out? Did they stay there for a couple of years? Was it an every couple of months sort of?

Doug Drewry: No. On the FGB team, now there were people, interestingly, while we were over there. I mean, some of the, some of the people involved are in great positions in NASA right now. Bill Gerstenmaier, he was in Moscow full-time trying to get the control center built up.

Host: Oh.

Doug Drewry: And, Mark Geyer’s the center director here. He was brought on as my schedules guy for FGB. And, Kirk Shireman is the Space Station Manager. He was my GNC guy. So.

Host: All right.

Doug Drewry: Basically, what I did is from the program office is I took subsystem specialists. I had mostly out of the engineering directorate. I had a small staff that was full-time FGB. The rest were all the technical experts that we pulled for all the subsystems from across the whole center. And, mostly, out of engineering. And, we developed relationships with direct counterpart for them in Moscow at Khrunichev. In some cases at Energia. And, they, the teams, my biggest job is trying to support everything that they needed to do to do their jobs to make things happen, you know.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: They were the technical expertise. My job was to make the decisions and give them direction.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: You know, my classic example is you’ve got a power team and a thermal team. And, the power team is trying to generate as much power as they can, which, of course, a byproduct of that his heat. The thermal team’s trying to cool everything down the best they can which will freeze everything if you let them. And, my job was to say, okay, you know, here’s where we’re going to cut this. We need a balance here, and it’s crossed in all the systems, the integration work. So.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: But, I rely very heavily on the real experts on their respective systems.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, the way we ended up signing the certificational flight readiness, you’ll see the U.S. signature, the Russian signature, British counterpart, the Boeing subsystem signature for each of the subsystems, and then I sign, and then, I think, Randy Brinkley was the program manager at the time. He signed, and the Russians signed. So, we’ve got accountability all the way through.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: So, back to your question. My teams, there was almost constantly someone there, in addition to the locals we had in the office. Depending on the phase we were in, sometimes there wasn’t anybody there. Other times, we would, we would have technical interchange meetings, probably every two to three months where we would take the whole team over either there or bring the Russians here and work out the details, particularly if we were making a modification or had an issue on something. At other times, it was smaller teams, groups of five to seven that we would send one way or the other, again, just to work things out.

Host: So, with that much going back and forth and with a lot of the folks based here in Houston, how did you oversee the project, then, from the states?

Doug Drewry: Well, we, again, we were in Russia lot.

Host: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Doug Drewry: Delta became a very friendly airline to us.

Host: Oh, I see. I see. Okay.

Doug Drewry: At one point, George Abbey actually chartered an airline, one of the old government charters.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: To charter us back and forth because we were carrying so many people back and forth.

Host: So many people so often.

Doug Drewry: We were constantly, I mean, you know, it’s like anything else. We’re in constant communication.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Phone, emails.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Computer links. We’re doing all these things. You know, so we had the, we had the technical side as well as the contract side. I mean, this was something that had never been done before, a collaboration like this. Because it truly was a joint effort. This wasn’t a piece of Russian hardware that we gave a few pieces to. It wasn’t U.S. hardware that the Russians had input on. We worked very hard on this as, and I would say it, you know, again, it’s the module’s different from the original Russian module that’s got all this integration in it. One of the things you carried over, some of the interesting things that, unique things about the FGB is since it was originally a Russian contribution, it kind of put us in a bad spot when all of a sudden they said we agreed that we were going to pay for the FGB because it was launched on a Russian proton. And, I wanted to avoid suddenly them coming back and saying, “Well, now you’ve got to pay for the rocket and you’ve got to pay for the fairing to put on it.”

And so, I rewrote the contract, or wrote the contract that we ended up signing with all that integrated, that they were still responsible for supplying this stuff because.

Host: Sure.

Doug Drewry: Our hands were full trying to build the module.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: And, you know, I mean, things from load testing. You know. I mean, I had people out there doing load testing, and we were running tests back here to verify things. And, we were busy on the technical side. So.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: We ended up having to waive some of the FARs to do some of the stuff we were trying to do.

Host: FAR?

Doug Drewry: Federal Acquisition Regulations.

Host: Okay. Okay.

Doug Drewry: There’s a set of, you know, they govern everything that NASA or the government buys. And, some of those things just wouldn’t work for what we were trying to do. One of the things is that on, when a contractor builds a piece of hardware and delivers it to the government, there’s a DD250 that basically transfers title. Well, I deferred that until the FGB docked with the service module because that was the first on orbit. Well, the first test was, you know, other than all the ground testing. The first test was successfully getting to orbit. That was a milestone. Successfully mating with the node was another milestone.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: And, that kind of checked out the other end. The next thing was until the service module’s docked, we couldn’t verify all those interfaces, so I put off the DD250 until after the service module was docked. And then, still held some money until we pulled into, subtracted the solar rays because that’s something that was not standard on a Russian, on any of the Russian designs. And so.

Host: Yeah. So, even the negotiations were ongoing, even throughout all that.

Doug Drewry: There was always something going on.

Host: Yeah. I bet.

Doug Drewry: Always, and trying to get hardware back and forth was interesting. I mean, we hand carried the mating, or the docking targets, the PMA targets to do the shuttle docking with that were installed on orbit or installed on the module before launch.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: Because we just had so much trouble getting things through customs sometimes. Even, you know, it’s kind of unbelievable the way people pulled together to make this happen in some cases.

Host: Wow. Yeah. That’s true because sure. Yeah. Instead of going through customs, you just avoid that and go above it.

Doug Drewry: Well, no. It’s not really avoiding that. It’s that, let’s put it this way. NASA had no special favors trying to go through U.S. or Russian customs.

Host: Sure.

Doug Drewry: Just because we have NASA stickers and critical space hardware all on it, sometimes that stuff would still get hung up.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: You had to go through bureaucrats on all sides, and sometimes, the only way around that was to put it in your hand, carry luggage.

Host: Yeah. That’s true.

Doug Drewry: And, that’s just something that, you know, you typically don’t do with space hardware.

Host: Now, you’re kind of referencing on top of Zarya, all this other stuff that’s going on. Because it is an international space station. You already said you were working on S1 P1.

Doug Drewry: Sure.

Host: These elements of the truss. So, how was the space station in the background while Zarya’s going through this development from ’93 all the way up through launch in ’98? What’s going on with the space station during that time?

Doug Drewry: Well, of course, all the space station hardware was progressing.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: To meet. We all had launch schedules we were trying to meet, and Bill Bastedo was leading the U.S. node 2A. All the hardware was progressing. I occasionally would talk to the people that, the same people that designed the S1 truss and would have done the P1 truss with me or the same people who were working on it when it finally launched for those managers. So, you know, they were all, everybody was pushing hard to get to where we needed to go.

Host: Yeah. Definitely. Now, eventually, you got to launch, right?

Doug Drewry: Yes.

Host: You oversaw a lot of launch as well.

Doug Drewry: I was there for the launch.

Host: Okay. You were there.

Doug Drewry: Oh, yeah. Oh, yes.

Host: So, tell me about that. Tell me about getting ready right before launch day up through the launch itself.

Doug Drewry: We had, well, I mean, we did all the check out of the hardware before it left Moscow.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: The Russians actually transported the hardware up to Baikonur. And, of course, we had, we’d been in Baikonur five or six times for things prior to launch day as well. I think we were there for the launch. We were probably there two or three weeks before the launch. I don’t remember exactly.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: When we showed up, but I mean, we had a lot of final reviews and things to do.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: On site. Some of the, again, things that you don’t really think about, but we, because this was a joint effort, I had JSC PAO people there. And, they were out setting up cameras, and they had been allowed to film a couple of the Soyuz launches before that to practice camera placement and stuff. They managed to fry a few cameras.

Host: All right. That close.

Doug Drewry: Oh, yeah, yeah. One of the guys here that was a good friend was, had come back from one of those. We had met in Baikonur one time, and he said that they’d been out setting up their equipment. And, one of the sites where they’d set up a camera, they look around suddenly, and all the Russians were gone. And, they figured they’d better get out of there, and they just barely got out before the rocket went off, and.

Host: No one told them.

Doug Drewry: No one bothered to tell them to move. So.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: So, it was a, you know, it’s a different, it’s a different environment.

Host: Definitely. I’ve only been to Baikonur once, Karaganda for a landing. But, you know, me coming in as late as I am in this already existing years and years, decades of experience.

Doug Drewry: Sure. Sure.

Host: Everything is pretty much, like.

Doug Drewry: It’s a process now.

Host: It’s a process. It’s routine now.

Doug Drewry: Right. Right.

Host: But, I’m sure, I mean, how was it going and doing all those things in Baikonur, this strange country, this strange place in Moscow. Nothing is set for you. You kind of have to build it from the ground up.

Doug Drewry: We did. I mean, everything was, like I said, when I first went to Moscow, it was black and white.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: We were followed. When we first went to Moscow, we were largely staying at the Penta Hotel. Probably still stay at the Penta or the Radisson. We would be escorted to our rooms by a hotel matron, I’ll call her.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, she would, once we were in our rooms, she’d lock the door. And, if we wanted to get out of our room, we called the desk, and they would come. They would escort us around, but we didn’t go anywhere by ourselves.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: When we were out on the street, we always had an escort following 50 yards behind us. Following everything we did. They said it was for our protection, but, you know, who knows.

Host: Sure.

Doug Drewry: In every meeting, pretty much clear to the end, we had a Russian security specialist, one or two guys, standing in the room somewhere who were just monitors. They never said a word, never did anything. They just kind of, I guess, made sure people did what they were supposed to do.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: It was, what was really interesting on that, as it turned out, is I flew B52s back in southeast Asia. And, we were at one of the after parties after one of the big TIMs, technical interchange meetings. And, one of these Russian security guys was there. And, we started talking because he was off duty. And, all of a sudden, this gentleman who had never said a word, he’s, of course, he’s had some vodka by this point. But, he’s very friendly, and we get to talking. It turns out he was a young lieutenant in the Russian Rocket Forces in Vietnam at a SAM site about the same time that I was dropping bombs over there. So, all of a sudden, we were the best friends. You know.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: From then on, every time he was involved in one of the meetings, he brought me patches. He brought me this, brought me that. It, you know, the way we crossed paths was just fascinating. I mean, there were.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: A lot of things like that that you don’t, you don’t appreciate, you know, until you.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: But, small world after all.

Host: Small world.

Doug Drewry: Yeah definitely.

Host: You in the cockpit, and him behind a SAM. That’s.

Doug Drewry: Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

Host: Very, yeah.

Doug Drewry: We couldn’t verify that we were ever exactly the same spot at the right time.

Host: Right, right.

Doug Drewry: But, we might have been.

Host: And, there you are, working together. How about that?

Doug Drewry: Yeah. So.

Host: Let’s jump back to launch. I think we got sidetracked a little bit, but.

Doug Drewry: Sure, sure.

Host: You know. You said you’re there a little bit beforehand getting everything staged three weeks before, I think. And then, comes right before the launch itself. This is at the, was this the Baikonur Cosmodrome, then? Or is this someplace else?

Doug Drewry: No. It was at Baikonur.

Host: Baikonur.

Doug Drewry: It was.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: Yeah. It was at Baikonur. We were there when the FGB came in and was lifted into the vertical and everything. And, it was a, it was a really unique experience and really pride moment to see.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: The NASA logo next to the RSA logo on a Russian rocket there.

Host: That’s cool.

Doug Drewry: That’s the first time it had ever been done.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: You asked earlier about other things were going on. While we were doing the FGB, John McManamen was trying to develop the docking adapter with them. So, that was off on the side that we ended up using and stuff. I mean, so there’s a lot of other activities going on.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: As we got close to launch day, of course, we had dignitaries from all over NASA and the U.S. and people showing up and they wanted to be there for the launch. The actual launch team, both Mark Geyer and Kirk Shireman were there. I had probably ten of the people from my team plus a couple from Boeing there for the launch. And, you know, it was fascinating to watch. It was kind of a cloudy day, so it would have been nice to been a little clearer. But.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Still. After the launch, we all gathered in a big auditorium, and you had all the agency heads for all the international partners up on the stage. And, we’re sitting in the front row, and it was an interesting thing to see.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: So.

Host: Were you getting communication from Mission Control in Moscow?

Doug Drewry: Oh, yeah.

Host: That everything was going well?

Doug Drewry: Yep, yep.

Host: I’m sure that was something to set up, too, was actually the mission operations side of things from Houston to Moscow.

Doug Drewry: Oh, yeah. Yeah. Clearly.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: I mean, we had quite a few issues. Like I said, Gerstenmaier was there trying to develop a control center in Moscow or.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: A concept, working concept. John Curry, I think, was, he was a flight director at the time. He was the one that basically did a lot of the FGB stuff with us, and it was a, you know, we had part of the ongoing discussions where who was going to be in control of this vehicle while it’s on orbit.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: For a year. And, you know, this is back where some of the Russians thought it should be a Russian only, and some of the U.S. said, “No. We’re paying for it. It ought to be us, and we’re involved in this, too. It should be us.” So, there were some interesting compromises worked out on some of that stuff.

Host: Okay. Well, in the end, what ended up happening? Was, who was monitoring it throughout the next few years?

Doug Drewry: Both.

Host: There you go. [laughter]

Doug Drewry: Both. We had a U.S. control center and a Russian control center. And, we had people there, and I’m sure they had somebody here. I was.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: I know I was back here for the 2A launch and, or in KSC and then back here immediately afterward for the docking.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: And then, and, I’m pretty sure there was a Russian representative for two here, so.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: There was, it was quite an achievement. I think everybody was really, you know, speechless.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Probably the word I’d use.

Host: Yeah, so this was a big project for you. You were the program manager for quite some time, and then, after FGB and, you know, you went through all this negotiation and reworks and how was this going to be framed for the future. What you do at NASA after that?

Doug Drewry: Well, kind of interesting. I went through that early negotiation through getting the contract resolved in Moscow and the initial direction. And then, I was planning on going back to shuttle. I’d done EVA stuff with shuttle before, and I was asked to stay on. And, I said, “Well, the only way I would stay on is if you give me the first flight or something else.” And, my theory was I’d been in space station for so long.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: And, we’d been through so many redesigns. I figure the first flight had the best chance of completing.

Host: All right.

Doug Drewry: Eventually. So.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, Doug Cook is the one who talked me into staying. Said, “Okay. You got the first flight.”

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: Several times during the five years it took us to build, I was actually turned down promotion of the Russian. I would have taken the Russian segment, and I turned it down. There was just too many, I felt there, for two reasons. There was too many things going on, too many things that were unusual about the FGB that we had done. Again, rewriting FARs, fighting with budget people outside of the agency, GAO and things. Not to mention all the technical things we had going on. And, plus, I felt I was in a unique position from beginning to end. I really wanted to see this thing launched.

Host: Yes.

Doug Drewry: So, I stayed to the very end. After that, I was talked into starting the external carrier’s office and space station. We built a bay 13 carrier. We built quite a few pieces of external storage platforms and things and figured out how we were going to launch spares to orbit for the station. After that, I went over to the structures division as a deputy division chief and ended up being there through all the Colombia stuff. Basically, my boss was off on a contract negotiation. So, I ended up acting chief for a couple of years then went to staff in engineering. And, after post Colombia and worked on the repair kits and things we were going to do there and ultimately ended up back in shuttle.

Host: Oh.

Doug Drewry: And, so, you know, I was at the launch for all the last flights and running the Debris Integration Team. And, I can happily say I was on the runway when the last flight landed. So.

Host: All right.

Doug Drewry: Literally, I was on the runway, so.

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: So, it was a, it was a fun career.

Host: Yeah. For sure. What’s interesting about, especially the beginning of your career is you were, I mean, you’re saying recognizable people to me. You know, I work with Shireman.

Doug Drewry: Everybody’s done well.

Host: Yeah. Everyone’s doing well. But.

Doug Drewry: They’re good friends.

Host: You’re a manager at this point, and this, throughout your career, managing and leading products. Tell me about what it took to be successful at that and despite all of these back and forths to manage a team and to execute the mission throughout the launch and beyond.

Doug Drewry: I would say two things. One is that you can’t be the, you might be the smartest guy in the room, but you’re not the smartest guy in the room. And, no matter what you know, you don’t know everything. So, my first philosophy is to always surround myself with the smartest people I can find.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, that’s where the subsystem people, subsystem managers, those were the real technical experts on their systems. I knew enough to be dangerous, and I could settle arguments and give direction after hearing the facts. You know, but, they were still the experts.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, you really need people that understand things and do those. As well as you need somebody to do the integration.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: The other thing is that I felt a big part of my job was to, as a NASA person and a NASA manager on a program like that or a project like that is to always try to get the best value for the American people. You know, the tax dollars. So, I felt it was important to just as if you were building a house or anything else, you’d want to, you want a good product, then you want a fair price on it. So.

Host: Yeah. So, it’s really about, you know, understanding what you need to do, understanding who is the best at doing it, and establishing good communications channels but never letting go of that perspective of why you’re doing it.

Doug Drewry: Well, yeah, you have to, you have to know where you’re trying to go. You know, the hardest thing is to ask, find out what’s the right question. Once you know the question, you can set about figuring out what the answer’s going to be.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, you can’t become so rigid that just like in this building hardware, you know, the Viewgraph engineering I mentioned on the front end. You look at these projects on the front end, and it all looks great. It looks like it’s nice and linear and things are going to work great. Well, that rarely works out, especially when you’re doing things that haven’t been done before or that, in the case of a lot of the space station hardware, you’re talking about building with materials that don’t exist yet. You have a design goal you’re trying to do something, but, and you know what you want to do, but you can’t just go off the shelf and put it together. You’ve got to develop the materials along the way so that you can do what you’re trying to do. And.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, when you’re doing things like that, there’s always problems. There’s always issues, and some, you’ve got to be ready to, you never throw away where you’re trying to go, but you may change a path to get there.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: If there’s a better path. And, you’ve got to be open to see that.

Host: Yeah. That’s true. You’re doing new things all the time and recognizing that is part of the learning process.

Doug Drewry: Sure. Sure.

Host: So, you know, you talked about your career going forward, even seeing being on the runway for the last landing. That was pretty cool. But, you know, you oversaw this first part, this first step in the International Space Station. And, you know, I’m working, right now, pretty closely with what it is today.

Doug Drewry: Sure.

Host: A functioning laboratory in space.

Doug Drewry: Sure.

Host: Constant habitation. Constant, hundreds of experiments per rotation. As a well functioning laboratory, and that’s what I know. But, you know, looking at the program from your perspective from the beginning, did you anticipate that this is where it was going to go? Did it exceed your expectations? Was it different from your expectations? Looking at it now.

Doug Drewry: It depends on the timeframe.

Host: Okay. Okay.

Doug Drewry: And, I say that with some hesitancy because when I first came into space station, there was a separate assembly node. I mean, part of the studies we were doing, there was going to be, the space station was being designed to support on orbit assembly of, and this was in the design phase, but on orbit assembly of lunar transfer vehicles and Mars return vehicles. So, the thing that’s always plagued us is that getting from the ground to low earth orbit is so costly. I mean, it’s such an effort, and so much energy is expended. That, if you can, and, of course, the bigger piece you make on the ground, the more technical difficulties, technically difficult as well as expensive it is to get up to orbit. So, if you can bring up smaller pieces and assemble them on orbit, then once you’re free of the atmosphere, you can, you can go almost anywhere, do almost anything.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: So, the original space station concept had this maintenance hanger out to the side, if you would. So that, you could, these lunar vehicles would come back and you would do engine change outs and things there. And then, there would be another vehicle that would return whatever payload or cargo to the earth. And, the transfer vehicle would go back to the moon and do whatever it’s going to do there. So, in some respects, it’s disappointing that we scrubbed all of that stuff out. I mean, I understand the realities and the difficulties of getting there and that, you know, this is all so difficult that it’s a stepping stone. And, again, when you had to develop things to do what you’re trying to do, you can’t just, you can’t just go buy it somewhere. You have to make it happen.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, but at the same time, we were always planning the core station to be a laboratory. And so, it doesn’t surprise me where we are on that. It’s what we built it for.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: And, I think it fulfills that role very well. You know, I think someday, we’ll go back, we’ll expand to those other things still. It’s just you got to take it one step at a time.

Host: Yeah. Now. Seeing just how, just the FGB and going through all the changes from the beginning, the inception of the program through all the changes, and then, finally launching. That kind of can translate, right, to the whole International Space Station? Just it did get together, but just it might take some time. You know, it’s still.

Doug Drewry: Sure. Sure.

Host: Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Doug Drewry: Sure. I probably get one or two, well, it’s not as often now. I probably get, still get one call a year somebody wanting to know something about the FGB.

Host: Oh, really?

Doug Drewry: Because I’ve still got all this data that probably no one else has.

Host: Oh, okay.

Doug Drewry: But, no, it was, like I said, it was, in the beginning, it was kind of the keystone element. It’s still a core part of the station. It’s probably, I’m sure the crews these days look at it as a storage module, place to shove things because there’s not really crew accommodations in there, per se, unless you want to hang out in the docking node and hide from everybody for a little while. But, it’s not where you really live and, like you do on the rest of the station or do experiments. It’s largely storage. But, at the same time, though, it is still the module that’s passing all that data back and forth and making those fluid connections and everything else from one end of the station to the other. So, it’s.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Still a core piece of the space station.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, in doing what it was, what it was intended to do.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Trying to integrate, basically, a U.S. design where we were with Freedom and then Alpha, with the Russian design where they were with Mir. And, the service module’s largely an offshoot of that. And, their concepts are still largely the same. There had to be something in the middle to bring that all together, and that’s what the job of the FGB was to do. So.

Host: Looking at you starting, you know, the FGB, Zarya, and then, towards the end, moving on to the next program. Before you did that, what do you think was some of your biggest, if not just the single biggest takeaways from the experience of your time as the program manager for FGB?

Doug Drewry: How amazing the NASA people are.

Host: Okay.

Doug Drewry: How similar some of our international partners are, yet different.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: You know, different, but how well people can work together when they really have incentive to do so.

Host: Right.

Doug Drewry: You know, but, yeah, the NASA people are just unparalleled, I think, in my mind they’re just fantastic people, and are capable of great things.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: You know.

Host: Definitely. I want to kind of end on this note, and it’s an international space station, and you worked internationally. And, you know, there were some ups and downs to it.

Doug Drewry: Oh, sure.

Host: There was challenges, especially going in. I mean, and I respect you for this is going in just, you know, you said you knew the day before. Here you go. You’re going to Russia. Make this work. But, you know, based on understanding, even through the challenges of working with different culture, what is the benefit of international collaboration?

Doug Drewry: There’s a lot of, I mean, on multiple fronts. Both just from getting to know other people around the world to, from the technical side. I mean, we, you know, my going in impression of the Russians, or the way I would still summarize it, for example, would be that we spend years and years developing a lighter weight material and refining a design. And, it takes us forever to get something launched.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: Whereas, the Russian approach was we’ll strap on another booster and launch a, you know, build it out of iron. And, well, that’s true in some respects, people don’t realize that in some cases, on the ISS today, Russian mandated requirements are more stringent than NASA’s requirements are in some areas. For example, we had a, there was a long discussion over many months or years about water quality because their standards for their crews and what they wanted were more stringent than what our standards were. And, ours are pretty stringent, as you can imagine. So, you know, it, another example would be having worked on the MB3 stuff. I had an ICD with shuttle that we were ready to, we were actually working our integration with shuttle for the MB3 launch for space station Freedom. Sitting through all those meetings with the orbiter people were kind of fascinating. I’d watch other payloads on the same flight, some of these universities and things that were trying to fly things. And, they would come in and, with their design, and I’d watch the orbiter people tell them “That’s not good enough. Go home, and, you know, come back another day.”

Host: Wow.

Doug Drewry: And, we’re talking months in some cases. One of those early meetings with the Russians. Of course, we had our people with us, and someone didn’t like something about the way the Russians were proposing to do something. And, they said, “Well, this is the way we do it at shuttle.” And, the Russians responded right back, “Well, we’ve been flying for 30 years, and we think that’s stupid.”

Doug Drewry: Oh.

Host: So, it kind of forced us to go back and look at some of the things that we had traditionally done.

Host: Yeah. Take a look at yourself.

Doug Drewry: And, some of our processes and things and.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: And, you end up taking the best of both worlds, I think, is what you’re really shooting for. And, I think the product of our collaboration is better than it would have been with either of us trying to do it individually.

Host: Yeah.

Doug Drewry: You know.

Host: Different perspective and maybe a little bit of humility.

Doug Drewry: Oh, most definitely. I mean, again, you’re not the smartest guy in the room necessarily. You know. You may go in thinking you are, but if you leave that way, something’s wrong.

Host: Yeah. Well, Doug, this has been a fascinating conversation and definitely an interesting perspective. It’s nothing that, you know, I did a decent amount of research to try to put this together, but this is, this was fascinating. So, I really appreciate you coming in and coming on today.

Doug Drewry: Glad to help. Any time.

[ Music ]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. So, it was a very interesting conversation with Doug Drewry. He gave us a nice perspective of that first launch that started the whole thing, the International Space Station, just 20 years ago. So, if you want to listen to more podcasts of everything going around NASA, we have Rocket Ranch, NASA in Silicon Valley, Gravity Assist hosted by Dr. Jim Green up at NASA’s headquarters. We’re talking about the International Space Station now. It’s the 20th anniversary, but we’re going to have launches and landings of astronauts and cosmonauts coming here soon to continue to live and work aboard the International Space Station. So, go to nasa.gov/ntv to find the scheduled on when that’s happening. Otherwise, you can follow all the happenings of the space station on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram where the International Space Station on all those accounts. Use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea. Make sure to mention it’s for Houston, We Have a Podcast. We’ll bring it right on the show. This episode was recorded on October 9, 2018. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, and Kelly Humphries. Thanks again to Mr. Doug Drewry for taking the time to come on the show.

Stay tuned for part two of our ISS beginnings episode with Mr. Jerry Ross to discuss the mission that followed Zarya, STS-88 and attached the Unity module to Zarya and the astronauts and cosmonauts entered the International Space Station in low earth orbit for the first time. We’ll be back with that episode next week.