“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and Johnson Space Center Director Mark Geyer describe the mission and direction of America’s space agency after a visit from Vice President Mike Pence. The two agency leaders discuss commercialization, human missions to the Moon, and the difference between NASA and Space Force. This episode was recorded on August 23rd, 2018.

Watch the full episode on YouTube.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center. Episode 63 — reach new heights and reveal the unknown. I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. So, if you’re new to the show, we bring in NASA experts and talk about all the different parts of this space agency. And sometimes we get lucky enough to bring in some of our leaders here at NASA. So, today we’re talking with Jim Bridenstine and Mark Geyer. Mr. Bridenstine is the 13th administrator of NASA, sworn in on April 23rd, 2018. And Mr. Geyer is the 12th director of the Johnson Space Center as of May 25th, 2018. Both very recent leaders. So, a little bit about our administrator. Bridenstine’s career in Federal service began in the U.S. Navy, flying the E-2C Hawkeye off the USS Abraham Lincoln Aircraft Carrier. It was there he flew combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. And accrued more than 19 hundred flight hours and 333 carrier arrested landings. He later moved to the F-18 Hornet and flew at the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center, the parent command to Top Gun. After transitioning from active duty to the U.S. Navy Reserve, Bridenstine returned to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to be the Executive Director of the Tulsa Air and Space Museum and Planetarium. Bridenstine was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Commander in 2012 while flying missions in Central and South America, in support of America’s War on Drugs. Most recently, he transitioned to the 137th Special Operations Wing of the Oklahoma Air National Guard. Also, in 2012 Bridenstine was elected to represent Oklahoma’s First Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served on the Armed Services Committee and the Science Space and Technology Committee. Geyer began his NASA career in 1990 at NASA Johnson in the New Business Directorate. He joined the International Space Station Program in 1994 where he served a variety of roles until 2005, including Chair of the Space Station Mission Management team, manager of the ISS Program Integration Office, and NASA lead negotiator with Russia on Space Station requirements, plans and strategies. From 2005 to 2007 Geyer served as Deputy Program Manager of the Constellation Program, before transitioning to Manager of the Orion Program, a position he held until 2015. Under Geyer’s direction, Orion was successfully tested in space in 2014 for the first time, bringing NASA another step closer to sending astronauts to deep space destinations. After supporting Orion, Geyer served as Deputy Center Director at NASA Johnson until September 2017. In this role he helped the Center Director manager a broad range of human space flight activities, including the Center’s annual budget of approximately 5.1 billion dollars. From October 2017 to May 2018, Geyer served as the Acting Deputy Associate Administrator for technical for the Human Explorations and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. In this position, he was responsible for assisting the Associate Administrator and providing strategic direction for all aspects of NASA’s Human Space Flight Exploration missions. Born in Indianapolis, Geyer earned both his Bachelor of Science and Master of Science degrees in aeronautical and astronautical engineering from Purdue University in Indiana. Geyer is now the Director of NASA Johnson Space Center. In this role, Geyer leads a workforce of approximately 10 thousand civil servant and contractor employees at one of NASA’s largest instillations in Houston and the White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Host: Today, I’m sitting down with our administrator and center director to discuss this very exciting period we’re in for human space flight. We discuss NASA as a whole, commercial crew, the commercialization of space, and the mission and direction of America’s space agency. So, with no further delay, let’s jump right ahead to our talk with NASA Administrator, Jim Bridenstine, and Director of the Johnson Space Center, Mark Geyer. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host:Jim and Mark, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today. This is such an exciting day. But also just an exciting time for us here at the agency. So, I appreciate you coming on today.

Jim Bridenstine:Great to be here.

Mark Geyer:Yeah. Thanks.

Host:So, just to sort of recap the events of today. We had Vice President, Mike Pence, here to address some fantastic missions and opportunities that we have here at NASA to look forward to. That’s what I. I really mean it’s an exciting time. So, if we can just give like a quick summary. Jim, if you want to.

Jim Bridenstine:You bet.

Host:For what was said today.

Jim Bridenstine:So, it was his opportunity to come and layout for the folks here at the Johnson Space Center, but also for everybody who works at NASA nationally, really his vision for civil space, for our journey back to the moon, for commercializing low earth orbit, for building SLS on Orion to get humans deeper into space than ever before. And really get the, get NASA and its workforce enthused about the next chapter of humans in space. And so, I would say based on his speech today, I think, I think it was effective.

Host:I absolutely agree. And he was here at the Johnson Space Center because we do play an integral role. So, Mark, what is the role of the Johnson Space Center in all of this?

Mark Geyer:So, Johnson has in the past and still plays an incredible core role to human space flight. So, we do, of course, we do the obvious things. The astronauts are trained and picked and flown from here. We do operations. So, we control the space craft and work with the crews here in mission operations. And then, also we do design work, like Orion, programs like Orion. We manage programs like Space Station, which ties the world together on an incredible program. Then, we do human health and performance, which is part of seeing how the body behaves in space. This kind of ties to our work with astronauts. And then, what was great about the visit today, I think, was he also visited the Curation Facility, which is where.

Host:That’s right.

Mark Geyer:In the — Really in the United States whenever we bring samples back from other worlds, they come here to do, to the Johnson Space Center. So, that’s a key piece I think a lot of people forget that we do.

Host:Yeah. A huge array of activities. A lot it dealing with research and sort of trying to understand what we need to know to go out further into space.

Mark Geyer:Exactly.

Host:And then, the actual technologies behind that. Jim, you were, you were appointed very recently here. So, you’ve been. When you first came on you said you recognize NASA as a family.

Jim Bridenstine:Yeah.

Host:Now that you’ve been here a couple months, do you feel like you’re part of the family?

Jim Bridenstine:Without question. Folks have been just so welcoming and nice. In fact, I had my family here at the Johnson Space Center just a couple of weeks ago. And what an amazing opportunity for my kids to be able to interact with the brilliant folks that are here. And really have a chance to spend time with some of the smartest minds in our country. So, yeah, it has been, it has really felt like a family. And having my family here really, I think, solidified that.

Host:That’s right. So, you’ve been. You’ve been a proponent for space flight and NASA just in general, even throughout your career. Now, coming here and being part of NASA, when someone comes up to you now and says what does NASA do, knowing kind of what we do from the inside now, what do you say?

Jim Bridenstine:We increase the awesome. That’s what we do.

Host:I love it.

Jim Bridenstine:As a — We are a part of the Federal Government that works on really, really awesome things. And, you know, my job as the NASA Administrator is really focused on making sure that we’re following through on the President’s space policy directives. His first space policy directive is that we’re going to the moon. And we’re going to go in a sustainable way. His second space policy directive is about regulation and enabling commercial partnerships. And, of course, his third space policy directive is about space situational awareness and space traffic management. And, of course, NASA plays a role and/or will benefit from each of those. And so, we’re really putting together the architecture that follows through on the President’s directives. And then, watching, you know, what the great workforce here does in enabling our missions to go forward in a really amazing way. So, people say, you know, what does NASA do? A lot of people, you know, you think about the history. There’s a lot of awesomeness in the history. And you think about the space shuttles and the retirement of the space shuttles. People remember that, remember those days going back to, you know, Gemini and Apollo and Mercury before that. And, of course, they remember the space shuttles. But at this point, we’re focused on getting American astronauts to launch on American rockets, again from American soil for the first time since 2011, the retirement of the space shuttles. And so, we’re going to get there. And look forward to being at the helm when all of that happens again.

Host:That’s right. This is one of those exciting things that I was talking about. You know, launching from American soil again. So, when we’re — I do want to go through all of these exciting things, right? Launching from American soil. This commercialization. This commercialization. This deep space exploration. But I want to know, since I have you here, what’s your role as the Administrator at NASA to make all of this happen?

Jim Bridenstine:So again, following through on the President’s space policy directives and then ultimately guiding the agency as you think about the policy and the directions that we’re that, the directions that we’re taking. You know, the, you know, my role is really guidance. And I work a lot with the interagency. A lot of people think space and they think NASA. But for all of our commercial partners, a lot of them provide things in space that are licensed, if you will, by the FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation. When you think about, you know, remote sensing and imagery, all the, all of that is licensed by the Commerce Department through NOAA. So, so there’s a lot of activity in space. The Department of Defense. The intelligence community. The Department of Transportation. There’s a lot of activity that isn’t specific to NASA where we need interagency kind of collaboration. So, I work with the interagency. I also work, as a former member of Congress, I work on the Hill to make sure that our, you know, budget requirements are being met to accomplish the objectives set forth by the President and, of course, by Congress.

They authorize, you know, what we’re supposed to be doing. And, of course, they appropriate the funds to accomplish those objectives. So, you know, my goal is to make sure that we are within, within the law. That we’re following through on the President’s guidance. And that at the end of the day we’re heading the right direction.

Host:So, with this guidance, with these directives, Mark, in the Johnson Space Center, what are we doing to sort of take this path?

Mark Geyer:So, we have, of course, we’re finishing the commercial crew vehicles and part of our job at Johnson Space Center is to be kind of the space craft expert. So, we’re —

Host:Okay.

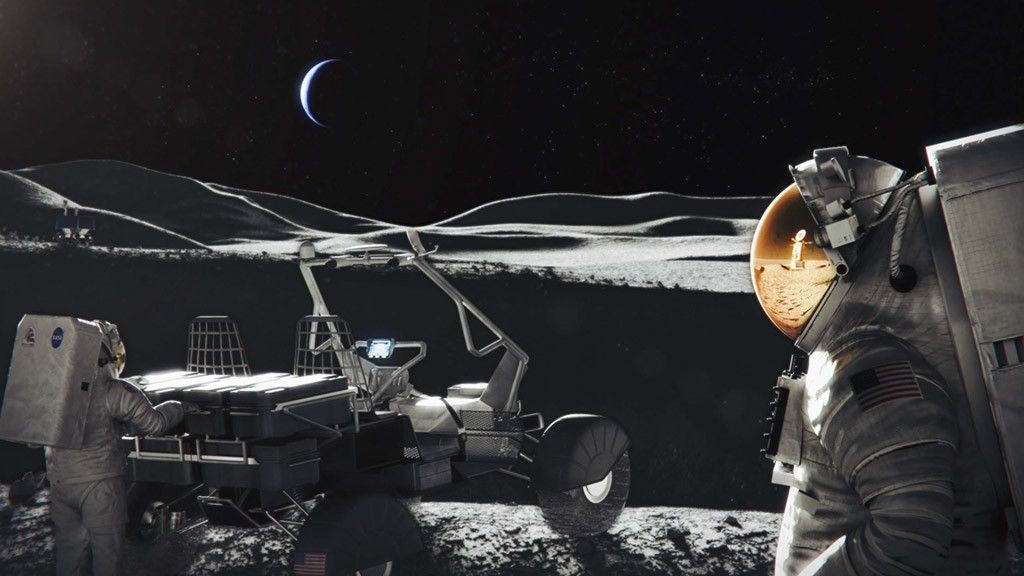

Mark Geyer:Following along with the providers. And following along with the design. And checking the requirements. So, we’re getting into a certification part of that. You know, are we ready? Are these vehicles meeting the requirements they’re ready to put our crews in them? And that’s going to be essential. Because we’re trying to basically operate the Space Station. Keep up the Space Station. And as Jim said, fly from U.S. soil. Cut the cost down. So, a key part of that is finishing that part of the job. And then on Space Station, of course, we’re doing research for how the human body behaves in long duration. And that’s a key part of any exploration plan, right? How are we going to keep our safe and healthy for these long duration missions? So, that’s a big part that we’re doing today that applies. The SLS Orion, as I’ve mentioned before many times, so we’re almost ready to fly. In 2020 we’ll be flying. And those are key missions that enable space policy directive number one, going back to the moon. Because you need that kind of energy that SLS provides. And the kind of systems that Orion provides to get a crew out past the moon. So, those are going to be very visible things in the near term. And then, really we’ve been working in them for a while about what we’re going to do around the moon, right? And how we’re going to use this gateway to basically provide access to the moon. And so, we’re in the early stages. But Johnson plays a key role in how that’s going to work and how that might come together. And we use our experience in how to partner with people, both international and commercial, to figure out the smartest ways to make that happen. So, we have a lot of pieces that we’re pulling together to help NASA implement that plan.

Jim Bridenstine:That’s right. When you think about the human physiology, which Mark mentioned, that’s one of the big reasons the first space policy directive by the President is to go back to the moon. We know because of the great work done here at Johnson, we know what happens to human physiology in a microgravity environment. We know that, you know, your bone mass will decrease by about one to three percent per month. And there are ways to mitigate against that. But there will be a degradation of the bone mass. We know that the heart will be deconditioned. We know that the neurovestibular system gets thrown out of whack while you’re in a microgravity environment and when you come back to a gravity environment. So, the question is, you know, if we’re going to send astronauts to Mars, they’re going to be in that microgravity environment for six, seven, eight, nine months. And once they’re at Mars, there’s no coming home for at least two years. While the moon gives us an opportunity to prove out, you know, can, you know, are there, are there ways that we can have an astronaut in a microgravity environment for six months and then send them to the moon. And see if that reverses the effects. Like when you’re in one sixth G, which is the surface of the moon, does that reverse the effects that you had in microgravity? And if it does, then we would know that in one third G, which is Mars, it would probably also be effective. But the reality is we can’t send astronauts for the first time after being in a microgravity environment for seven months, put them on the surface of another world and have them be perfect. They have to be perfect in order to stay alive for two years.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:And proving that out at the moon is really the best way to do it. And so, that’s what space policy directive one is all about, as well as retiring the risk for a lot of the technologies and the capabilities.

Host:That’s right. Yeah, that’s, that’s one of the things, one of the nice things, I think, about the International Space Station is that it’s so close Two hundred and 50 miles sounds pretty far. But honestly it’s pretty close to home. If anything goes wrong, you can come back. It’s the perfect place really to test a lot of these capabilities. And that’s, I think, where the commercial crew comes in, right? Now, we’re doing this certification process. We’re working with Space XM Bowing very closely to provide us the capability for low, to access to low earth orbit. But it’s not just that, right? We’re talking about the Space Station. We’re ending direct federal funding in 2025. Building a low earth orbit economy, something that’s, I don’t think, been done before. What’s. So, that’s part of this directive, right? Is establishing an economy in space. So, how are we doing that?

Jim Bridenstine:Yeah, that’s a great question. And we’re going to have to work through it.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:You can imagine there’s all kinds of technologies and capabilities that have been developed already. And Mark has been really good about talking about how the Space Station, the International Space Station, has really been a key driver of enabling us to commercialize low earth orbit. If there is no Space Station, there would be no commercialization. And so, it has been a very effective tool for building the space economy, if you will. And now, when you think about what the future holds, even experiments that are happening right now, you think about fiber optics being manufactured on the International Space Station, which could drive down the cost for in essence making, not just America, but the world more connected. You think about the ability to produce pharmaceuticals in a microgravity environment, where you can do things that you cannot do on earth. You think about taking adult stem cells and 3D printing human organs to increase the, you know, the lives of humans. All of these things are being developed right now with the support of NASA on the International Space Station. And each one of those things is a market unto itself. And there’s so much more, right?

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:So, what we want to make sure. And on another piece of this, you know, we talk about commercial crew. We’re going to be launching commercial crew here in the next year. We’re talking about, as we’ve talked about sending American astronauts on American rockets from American soil. All of that is fantastic. But these commercial crew providers in many, they have seats, they have seven seats on their space craft. Which means we could be flying tourists to the International Space Station. In other words, there’s. And I’m not saying we’re going to do that. I’m saying that is an opportunity that we need to look at. Because there could be a day when we have not just tourists, but, you know, different types of scientists, different types of even journalists flying to the International Space Station to share with the world kind of what’s, what’s happening in low earth orbit. So, there’s all kinds of ways for the International Space Station to become more commercialized between now and 2000, 2025. That’s seven years from now.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:There’s. Between now and then, there’s a lot that’s going to change. And it’s not just the International Space Station that could be more commercialized. It would be other private habitats in low earth orbit that would be adding to that marketplace in low earth orbit, so. There’s a lot of really exciting things happening. What we want to make sure we do, though, and Mark and I have talked about this, we want to make sure that we’re planning today for a future where we have no gaps in low earth orbit. We don’t want to have a day when American astronauts are not there. Kids that are graduating from high school today have lived their entire lives with a human living and working in space. We want to make sure that that happens, you know, 18 years from now. And then, 18 years from then. So, there’s no gap. And so, that’s really what we’re working to achieve now.

Host:That’s right. And it’s already under work. Mark, I know just recently the NASA research announcement came out. We selected companies to actually take a look specifically at this. What can we do? Right? So, what’s going on there?

Mark Geyer:Yeah, exactly. That’s a great lead in, because we are, you know, we NASA, we’re smart people. We’ve been partnering with people for our whole history. So, now we’re asking people that are on the cutting edge of commercializing space and some are suppliers. Some are creating demand sides. So, we ask them, what would you do? Right?

Host:Right.

Mark Geyer:What do you think makes sense as a company that would enable you? And what do you think NASA’s doing that’s stopping you? So, let’s talk about both of those. And what are the things we can do as an agency to help that? Because we, because as Jim said, that’s the goal. We’re trying to be. And I like the phrase — one of many customers. So, how does that happen? That means these other folks need to be customers. These other folks need to have a reason to be in space. And so, how do we enable that? So, we’re really casting a wide net. Asking people who have, not just people who are thinking, but people who have actually done commercial ideas in space. And say, okay, how would it work?

Host:That’s right.

Mark Geyer:So, we can put together a real plan. I think that’s the key.

Host:Yeah, work and then also be sustainable.

Mark Geyer:Exactly.

Host:Something that’s a business opportunity. Something that you want people to come and participate in.

Mark Geyer:Exactly.

Host:You know, it’s, it’s something that commercial industries can profit from.

Mark Geyer:Yeah. I think we see when, if. If I could just add to that.

Host:Yeah. Sure.

Mark Geyer:I think we’re seeing on Station with the National Lab and other things where it’s not, it’s not real, real simple to start a company in space, right? It’s not real, real simple to start creating a product in space. It takes some help from NASA just to get up there. It takes people with expertise about what happens in space. And then, it takes trial and error. So, the National Lab is a great example, where we take people who are interested, who are normal space folks that have been in space. All sorts of different companies. And then, we give them a talk about the opportunities. We tie them with people who have capabilities. We link them with people who have money. Say, hey these people might be interested too.

Host:Yeah.

Mark Geyer:Because it’s seeding that that’s really, really important. And I think what’ll, the key was if one, when one of those takes off where somebody really starts making money in space, that’ll be great for us. We just need to get out of the way. Because they’re going to be doing their thing. And that’s really going to help us reduce our fixed cost, because they’ll be buying services too.

Host:For sure.

Mark Geyer:So, that’ll be good.

Jim Bridenstine:And then, when that happens, as Mark said, we will be, NASA will be one customer of many customers, which drives down our price. But we’ll also have a lot of providers. When I say a lot of providers, we’ll have a lot of launch providers. We’ll have a lot of potentially commercial space stations that we can take our NASA astronauts to on commercial launch providers. And then. So, if you have multiple providers and we are one of many customers, then they’re competing on innovation. They’re trying to do more in order to become bigger. You know, they want us to be an even bigger customer. So, they’re going to compete on innovation. They’re going to compete on cost. That means NASA can do more than it’s ever done before. It also means that we’re going to be able to take our resources from the taxpayer and do things for which there is no commercial marketplace. We can fly to the moon on SLS and Orion, which right now there isn’t a commercial capability there. And, of course, we can build the gateway. And the first gateway is about more access to more parts of the moon than ever before. And the second gateway is a deep space transport that takes us to Mars. So, all of those capabilities are dependent on us commercializing low earth orbit. We don’t want to lose low earth orbit. We just want it to be commercialized. And then, we can take our resources and do things where there is no commercial market yet.

Host:Yeah. We don’t want to lose it. It goes back to your point of saying, continuing access, right? We still want to be a part of that, NASA as one many customers, but also the access, you know, for astronauts too. And even for private companies to send people up there. And that’s actually a money making endeavor as well. But then, you know, while we’re also doing that, there’s this economy down there so we can focus on, like you’re saying, exploration. And this gateway thing, I don’t think is something we’ve touched on so much on this show. So, we’ve, what is gateway? What is this thing?

Jim Bridenstine:So, the idea is space policy directive one says we’re going to the moon.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:It also says that we’re going to go sustainably. In other words, we’re not going to do flags and footprints again. But this time when we go to the moon, we’re going to stay. So, one of the ways to make sure that we don’t come home is to put a space station around the moon for a very long period of time. And, you know, it’s going to have solar electric propulsion, which means very high specific impulse. In other words, the fuel economy will be very, very high.

Host:Nice.

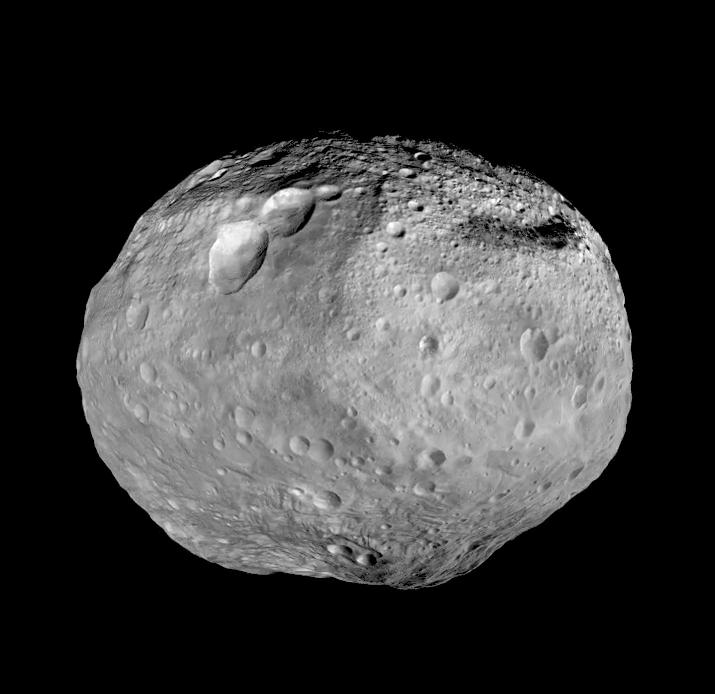

Jim Bridenstine:So, it can stay there for a long period of time. And it’s in what’s called a near recto, Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit, which means it’s kind of balanced between earth, you know, earth and the moon are, you know, the gravity wells of the two planetary bodies. So, all of that being said, it can be there for a long, long time. And then, what we need is we need reusability. We know what happens with reusable launch. The costs go down. Access goes up. We need, you know, tugs between earth orbit and lunar orbit to be reusable. We need landers that go from that gateway, that space station and orbit around the moon. We need landers to be reusable. All of that reusability is what makes everything sustainable. The other thing that’s important is when we go to the moon, we want to have access to every part of the moon, not just the equatorial regions. From 1969 when we first landed on the moon all the way up until 2008, 39 years, we believed that the moon was bone dry. And in 2008 and then more in 2009, we discovered that there’s hundreds of billions of tons of water ice on the surface of the moon. Water ice represents, you know, water to drink, of course. But it also represents air to breath. And it represents rocket fuel. Hydrogen and oxygen ultimately when separated into its component parts and put into cryogenic form, that’s rocket fuel. Now, space policy directive one signed by the President, actually talks about utilizing the resources of the moon. So, again, we want to go sustainably. We want to not do flags and footprints. We want to be there to stay. We want to utilize the resources of the moon, namely water ice for now. But it’s also true and we don’t know, but it’s true that there could be, you know, platinum group metals on the surface of the moon. Rare. You know, on earth we call them rare earth metals. But they’re really asteroid impacts from billions of years ago. Well, the moon has the same, the same, you know, path that the moon has through the solar system.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:Which means that it probably impacted the same asteroids that the earth has impacted, which means there could be a lot, it could be trillions of dollars worth of platinum group metals on the surface of the moon. We don’t know. But certainly we should find out. And it should the United States of America that finds out. Not somebody else.

Host:Right. Yeah. So, I like this idea of gateway, because basically what you’re describing is developing, not only the Space Station and access, but also a capability, a flexible capability.

Jim Bridenstine:That’s right.

Host:So, it orbits the moon, but basically after that you can kind of decide, oh, it’s all about exploration, right? So, as soon as you find something new, you can, you know, oh let’s go check that out. Let’s go check that out. It’s enabling this access. It’s an awesome time. And the thing that’s going to take us there, right? Is the space launch system, right?

Jim Bridenstine:Yeah. And, in fact, commercial partners as well.

Host:Oh, okay.

Jim Bridenstine:It’s all going to be open architecture. So, whether people are docking or using the power of the gateway, you know, we want our commercial partners to be able to build their own landers. We want our international partners to be able to build their own landers. The goal here ultimately is for the United States of America to assume the lead and then enable our commercial and international partners to do more. And, and be there for a very long period of time, so that we can learn scientifically more about the moon than we’ve ever known before. Like I said, we first discovered water ice in 2008. What else do we not know about the surface of the moon? And I’m willing to bet there is a lot we don’t know.

Host:That’s right.

Jim Bridenstine:And then, ultimately, again retiring the risk on a lot of these capabilities and technologies so that that gateway can be, in the long run, the second gateway can be our deep space transport to get us to Mars. And we want this entire architecture to be replicable. Like, we want to be able to take it to Mars. And that’s the objective. Now, I know, you know, Mars and the moon are not the same. Mars has an atmosphere, which makes entry descent and landing a little bit more challenging. But at the same time, as much of it that we can replicate we want to be able to replicate.

Host:For sure. Another thing you’ve been touching on is this idea of leadership. The idea of Americans leading this effort.

Jim Bridenstine:That’s right.

Host:So, why is this important to this, to this directive?

Jim Bridenstine:So, a lot of people don’t realize the soft power capability of NASA. This is really, you know, early you asked what do you do as the NASA Administrator? Well, really about a month ago, I was at the Farnborough Air Show in England meeting with the heads of space agencies from around the world. And the idea. You know, I was going to sell this new space policy directive that we’re going to the moon and we’re going to do sustainable architecture at the moon and we want our commercial and international partners to join us in this effort. I thought I was going to have to do a hard sales pitch. And the reality is they’re ready to go. It was really easy. They’re saying to me, tell us what you need us to do and we’ll go sell our governments, because we’re ready. They’ve. A lot of countries around the world have been waiting to go to the moon. And they just needed, you know, the leader. And that’s who we are. We lead. You know, the other thing that I think is important about NASA, when relationships break down around the world and, of course, you can probably tell that we’ve had a strained relationship recently with Russia, we’re able to continue to cooperate on space related activities. Civil space related activities. Which has enabled us to do more. It’s enabled them to do more. And that’s really a line of communication that would not be available without NASA. So, NASA represents an amazing opportunity for the United States of America to lead. It represents a soft power capability. And really an open channel of communication when other channels fail. So.

Host:So, I know, and so kind of along these lines of American leadership. And it’s, it goes back to this idea of corporation, right? It’s something that we’re doing right now. And Mark, you’re very familiar with it, right? You’ve work in the Space Station program for a long time. You yourself were a leader to actually work with Russia and make things happen. So, describe how, it’s, it’s called an International Space Station. It’s called that for a reason. It’s because it’s all of these nations coming together to make this thing, this single idea possible. So, how does that, how does that work? This international cooperation.

Mark Geyer:I think it’s a great lead in or tie to your previous question too, because really it was NASA, United States that said, hey we want to do this space station. And hey we want to do this with other folks. And then they came along side and did it with us.

Host:Yeah.

Mark Geyer:But to do that, so to lead, you know, to be a good leader. One you have to have a vision. But two you also have to listen, right? You have to understand your partner’s common goals. And so, unifying around common goals is really important. And that was a lot of what we did with the Russians in the early stage. You know, you set a policy, but then you sit down across the table and talk about what drives them, right? What’s likely to enable support within their country for them to get the funding to do the things that that they need to do. And so, a lot of that is you find out that’s what makes these kind of partnerships work. So, stations a big example of that. Not just the Russians, but, of course, Europeans, the Japanese, the Canadians. All of them have their own thing, right? They have their own thing that they’re interested in. There only thing that drives them. And so, you’re trying to find the common that still meets NASA’s and the United States goals. So, as Jim said, we’re taking that experience then out to the moon. Because Orion has a European component, right? The European service module is a big piece of Orion.

Host:Right.

Mark Geyer:It’s. And that’s a strategic decision to go partner with them to make that piece of Orion. So, it’s the beginning of us leading now into the next phase. And Jim said also for the gateway there’ll be international and commercial partners as part of that too. So, it’s taking that experience. I think we’re learning better how to partner with commercial folks, because they have their own things that drive them, right? And how do we find common, common goals that help them help their company, but still line up with what we want as a nation? So, it’s a skill that not a lot of people have. It takes time to learn how to do it. But it’s, it’s always exciting and it’s a big part, I think, is what’s going to make us sustainable, as Jim said, in the future.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:And one of the challenges that you kind of touched on is commercial partners are one type of partnership. International partners are another type of partnership. And we want to enable commercial to join us, as we develop our next generation of capabilities. And they want to join us. The challenge is how do you, if you’re developing this architecture and you want commercial partnerships in it, how do you then include international partners as well? And so, the idea would be well we bring in our commercial partners, they bring in their commercial partners and then we partner at the agency level with all of our commercial partners kind of in the mix. Well, there are some countries that don’t have commercial partners. They don’t have commercial space capabilities and in fact I’ve met with one country in particular who, you know, told me that they’re not interested in commercial. And that, you know, they’re not real thrilled about our commercialization of space. And I said, well tell me why is that? We can do more now than we’ve ever been able to do before. Why is that? And this particular person said, well we don’t have private capital in our country. Which kind of was eye opening for me. We don’t have private capital. So, to the extent we partner with some countries that have a different way of doing government and business.

Host:Right.

Jim Bridenstine:You know, we have to think carefully about how to include them in an era when we want commercialization and they’re not there yet. And in some of these cases and I’ve talked to some countries, they’re working really hard to develop a commercial capability that doesn’t yet exist. Which is also, that’s good to see. That’s American leadership. That’s NASA leadership that’s going to enable us as humanity to do more than we’ve ever done before.

Host:That’s wonderful. I feel like there’s this sense of American inspiration as well. Because we’ve been working with companies now or nations for, with the International Space Station for almost two decades now, right? So, so, it’s this constant cooperation that kind of gets the wheels turning and makes things work. But are you seeing a change in the landscape? Are you seeing that it’s growing? That more companies and more industry are wanting to take part in space exploration and even commercial space?

Jim Bridenstine:Mark, do you want to take that?

Mark Geyer:Yeah. I think you can see it in just the variation of the companies that are working on payloads and other things on Space Station. Companies that have grown up basically really providing a capability nobody thought of before.

Host:Right.

Mark Geyer:Like an airlock to then use to fly small satellites, cubesats, right? Something that we didn’t think about a lot. Now, Station I think is the number one platform for launching these satellites into space. So, things we hadn’t thought of before. Companies are coming up with that. And so, the key is, as we’ve talked, just providing a framework where you can get that innovation, right?

Host:Yeah.

Mark Geyer:And getting enough framework that we make sure hey Station’s going to be okay. But then, giving enough room so they can innovate and find niches that we would never have thought of before. So, we’re seeing that a lot in Space Station.

Host:Almost a different way of doing business.

Mark Geyer:Exactly.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:But there’s also, even beyond NASA when you think about what’s happening with communication architectures where it used to be in order to do over the horizon communication, you had to launch to geostationary orbit. And the satellites were five hundred million dollars. And they were, you know, the size of this table here. And now, we’re seeing constellations of thousands of satellites being launched into low earth orbit that are the size of a dishwasher. And that’s going to enable low latency, high throughput communications. In other words, it will meet the same standard as cell tower communications. Your cell phone will be able to work where you are in the world. You could be in rural Alaska or you could in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and your cell phone will work from any of those locations. Which will connect, you know, there’s still two thirds of the world that’s not connected. Well, at that point anybody who has a cell phone is now connected to the rest of the world. So, those capabilities are being launched and there’s half a dozen different companies that are launching those types of constellations into space. And each one of those companies will be able to benefit NASA when you think about the communication architecture that we need in space. And ultimately, the type of communication architecture that we’re going to need around the moon. And maybe even at Mars. So, there’s a lot of, a lot of commercial capability being developed right now that’s going to be tremendously valuable for, for NASA.

Host:Right. Capability, opportunity, everything really. I know, something else new is we’re in this time now where, where the administration is suggesting a Space Force, right?

Jim Bridenstine:Yeah.

Host:I actually had my mom text me and say, how does this affect you? Does that mean NASA’s going to away? I feel like there’s, there’s sort of a disconnect going on here. So, how would, how do you describe to those who are confused Space Force and NASA?

Jim Bridenstine:Great question. NASA does exploration and discovery and science. We do not do national security and defense. Of course, we do have an ability to do international relations and soft power, leadership, those kind of things.

Host:Right.

Jim Bridenstine:But we don’t get involved in the hard power activities of the country. Intentionally. You go back to 1958, the creation of NASA, Eisenhower was absolutely adamant that NASA not be part of the national security apparatus. So, that’s, that’s a good thing for our agency. At the same time, the Space Force, when you think about what it is, it’s really. You look at Air Force space command. They’re responsible for organizing and training a cadre of professionals that can do space security activities. And then, the space and missile system center, which is another Air Force command, is responsible for acquiring assets for space defense, space security. So, you take those, those components, the Air Force space command and the space and missile center and you take them out of the Air Force and you put them under a new secretary, a secretary of the Space Force. And you have them represented on the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And that in essence becomes your organized, trained and equip function, which is all that a military service is. A military service is responsible for organizing, training and equipping a cadre of professionals to fight in a certain domain. So, all of that could be, in fact the, you know, the plan is that that’s, you know, it would come really out of the Air Force. Now, the benefit of creating a separate force is then it has a line item that is equal to that of the Air Force and the Navy and the Army and the Marine Corp and it doesn’t have to compete against the air domain for resources. Don’t get me wrong. It will have to still compete, because at the end of the day the budget is only so big. But it will have its, it will have the ability to compete on the same level as the Air Force, the Navy and the Army. So, all of that, I think, is really what the Space Force is all about. If you listen to what the Vice President announced a number of weeks ago. He also said that they want to create a new combatant command. So, the military service organizes, trains and equips the cadre of professionals. But ultimately war fighting is done by what’s called a combatant command. In this case, it would be a functional combatant command. People are really familiar with what a geographic combatant command is. Geographic meaning like where in the world is it. So, centcom is in the Middle East. People are familiar with centcom. Or European command, African command. There’s the Pacific command. All of these different geographic combatant commands. In this case, it would be a functional combatant command responsible for fighting and winning wars in space. The idea being, you know, NASA and our commercial partners and other commercial entities, you know, we have hundreds of billions of dollars in space. Hundreds of billions. Plus we have our astronauts in space. And so, they. We need security.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:And what we have to do is we have to make sure that any potential advisory that we may have, any potential advisory looks at the space domain and they see that they aren’t going to get any kind of advantage by destroying it. They cannot win. There is no advantage. And in fact, if they tried, it wouldn’t work. That’s the goal. And if we can deter them from taking a war into space, then the rest of us, all of humanity can use space for our peaceful purposes, which is what ultimately we’ve been doing now since NASA’s creation in 1958. So, as a member of Congress, when I was in Congress, I voted for the Space Force three times. And it passed the full House of Representatives. And it passed in a strong bipartisan way. It got 344 votes. And, of course, it went to the Senate and it didn’t pass the Senate. But there was strong bipartisan support in the house. The President has seen the same intelligence that we’ve seen in the Congress and he took it up a notch and said we go to get this done. And I think he’s right.

Host:Awesome. And in the meantime, NASA is leading this cooperative exploration goal, right?

Jim Bridenstine:That’s exactly right.

Host:And so, its part of our, its part of our vision is reach new heights and reveal the unknown. So, as we’re wrapping up and to be conscious of your time, this, this meaning, this reveal the unknown, reach new heights. What does this mean to you? And we’ll close with that.

Jim Bridenstine:So, it really, you know, we are learning new things every day. Just since I’ve been the NASA administrator, a little over three months, we have discovered in these a little over three months, that Mars has a methane cycle that is perfectly in tune or keeps perfectly with the seasons of Mars, which doesn’t guarantee that there’s life, but it increases the probability that there’s life. Complex, complex, what is it? Compounds. Organic, organic compounds have been found on Mars, which again doesn’t guarantee life, but it increases the probability of life on Mars. We’ve also discovered now, just maybe a couple weeks ago there’s liquid water one and a half kilometers under the surface of Mars. Now, that doesn’t again guarantee life. But liquid water is a good. You need liquid water for life. And the fact that its one and a half kilometers underground means that it’s going to be protected from the radiation environment of deep space. Which all of this, you know, adds up to say is there life on Mars? We don’t know. But we need to find out. And to the extent that somebody finds life on a world that’s not our own, it needs to be the United States of America. So, that’s what we’re doing. We’re making discoveries. You know, we’re going to launch in the next three years, the James Webb Space Telescope. And we’re going to see back to the very dawn of time. Cosmic dawn. The first light in the universe. We have ideas and models as to what the universe looked like when it was first created. But we know that those models are all wrong. We need to. And so, we’re going to see it with our own instruments. So, the James Webb Space Telescope is not just going to look all the way back to the very first light in the universe, it’s also going to see back all the way out to the edge of the universe. Where we have galaxies that are accelerating, you know. You know, as the universe expands, it’s expanding at an ever increasing rate. The universe is accelerating away from a point in the center. And that expansion ultimately is demonstrating that there’s a force at work here. And that we don’t understand, we talk about things like dark energy and dark matter. Things that we can’t detect, we can’t interact with. But what we do know is that, you know, we see its gravitational effects. And we see these galaxies accelerating at the edge of our universe to the speed of light. So, they just disappear. Well, we’re going to be able to look at all those. We’re going to be able see inside of other galaxies. We’re going to be able to see within our own galaxy. We’re going to be able to see planets around other stars. And ultimately, make determinations whether or not those planets have a habitable kind of atmosphere. We’re going to be able to determine what type, if these planets have atmospheres, what those atmospheres are composed of. And if there could be life there. So, look NASA is doing really amazing things. And every day, we’re making new discoveries. And the more capability that we’re putting into space even right now, we’re going to have so many new discoveries, we’re not going to able to, you know, communicate all of them fast enough. Which is a really good problem to have.

Host:Yeah.

Jim Bridenstine:So, we’re learning more about, more about our universe. Are we alone in the world? And these are, these are important questions for us to answer.

Host:Wonderful. Mark, any, any final thoughts before we wrap up?

Mark Geyer:I think there’s some other things about NASA that I know changed my life. You know, I remember the first pictures from Mercury and Gemini about the earth from space, which changed, which no one had seen before. So, it changed our whole idea. And then, as Jim in an earlier speech today was talking about Apollo Eight. And I remember seeing the earth come up over the limb of the moon and remembering what that felt like to see ourselves in the solar system from a distance. It changed everybody’s idea of kind of how important the earth was. Those were, really changed our whole perception. I remember when Bob Cabana and Sergei Krikalev went together through the hatch of the node the first time on Space Station, right? Joining together. so, I think those images along with the discoveries, those images, I think, can change the way we see ourselves in the world and can be really, really important. And I think with this new exploration campaign we’re going to see many more of those things.

Host:That’s wonderful. This is such an exciting time. Jim and Mark, thank you so much for coming on the show. And sharing these wonderful insights. It’s really a pleasure to talk to you today.

Mark Geyer:Awesome. Thank you.

Jim Bridenstine:Thank you so much, Gary.

[ Music ]

Host:Hey, thanks for sticking around. I had a great conversation with our Administrator and Center Director here at Johnson Space Center. We talked to Jim Bridenstine and Mark Geyer. They’re both on Twitter. So, you can follow them specifically if you would like. On Twitter it’s @jimbridenstine for our NASA administrator. And it’s @directormarkg for our Center Director here at the Johnson Space Center. There are a lot of other NASA podcasts that you can listen to. Houston, We Have a Podcast is one of them. Another out at headquarters is Gravity Assist hosted by Dr. Jim Green. We have NASA in Silicon Valley out of the Ames Research Center. And then, Rocket Ranch out at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. You can follow us on social media, NASA as a whole agency to see what we’re doing just across all of these different areas. NASA is on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram under @NASA. You can use the hashtag ask NASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for this show, Houston, We Have a Podcast. Just make sure to mention Houston, We Have a Podcast in the request so we can find it.

Host: This episode was recorded on August 23rd, 2018. Thanks to Alex Perryman, John Stoll, Pat Ryan, James Hartsfield, Dylan Mathis, and Devin Boldt. Thanks to Matt Rydin and John Yembrick at NASA’s headquarters for helping this to come together. Thanks to Stephanie Castillo here at the Johnson Space Center also. And also, thanks again to NASA Administrator, Jim Bridenstine, and Johnson Space Center Director, Mark Geyer, for taking the time to come on the show. We’ll be back next week.