From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 297, Deputy Associate Administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate at NASA joins us this week to discuss future architecture plans for Moon to Mars missions. This episode was recorded on June 16, 2023.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 297, “Moon to Mars Architecture.” I’m Gary Jordan, I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. We talk about NASA’s Artemis missions quite a bit on this podcast. Mostly, we talk about the near-term goals of establishing sustainable human presence on the lunar surface through technologies and programs like the Orion spacecraft, Space Launch System rocket, Gateway lunar orbiting platform, new lunar spacesuits, landers, and more, including the interesting science on the Moon.

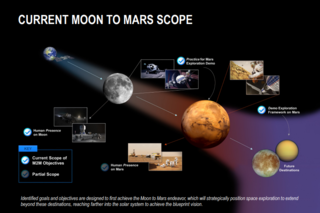

Now, you might hear NASA say, “Moon to Mars, Moon to Mars,” and you’re like, “OK, sure.” But that’s not just a little hop from a Moon to a planet. Exactly how does this all fit together? Earlier this year, NASA published the outcomes of its first architecture concept review, including the architecture definition document that provides a deep dive into NASA’s Moon to Mars architecture approach and development process. A series of brief white papers addressed frequently discussed exploration architecture topics as well. And NASA has already started its process for its 2023 architecture concept review with plans for yearly reviews to incorporate new technological capabilities and evolving objectives.

Whew. Lot of terms there.

And honestly, these are just a few of the efforts and documents that NASA has posted on this subject. It can be quite daunting to get a grasp on the whole thing. Well luckily, for this episode, we’re bringing in Cathy Koerner, Deputy Associate Administrator for the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate at NASA’s Headquarters in Washington, D.C. She first started her career at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Then moving here to Houston for most of her career, where she served in various roles, including flight director, leadership roles in the space shuttle and space station programs, she served as the director of Johnson’s Human Health and Performance directorate, and then as the manager of the Orion program before her current post. She’s been on the podcast before in one of her former roles, but now, she’s returning to help us digest NASA’s plan to expand human presence into the solar system. With that, let’s get right into our conversation with Cathy Koerner. Enjoy.

[Music]

Host: Cathy Koerner, thank you so much for coming back on Houston We Have a Podcast. Good to have you.

Cathy Koerner: Thank you for having me back.

Host: It’s been a while since we’ve talked.

Cathy Koerner: It has.

Host: I think you were part of one of our earlier episodes. And when we talked, you were the director of Human Health and Performance. So, what have you been up to since?

Cathy Koerner: Well, let’s see, since I was the director of Human Health and Performance, I had the awesome privilege of becoming the Orion program manager. Did that for about a year, year-and-a-half, and then got a really neat opportunity to go to Headquarters and be Jim Free’s deputy as the Deputy Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems Development, which is where I am today.

Host: All right. And that is quite a title, right? For Exploration Systems Development. What exactly is your role and what does that mission directorate oversee?

Cathy Koerner: So I actually do two roles currently, within the ESDMD (Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate) mission directorate. So the first is Jim’s deputy, which means, I get to be deputy over all the things that are within our portfolio, and we do everything human exploration that pertains to Moon and Mars.

And by that, I mean SLS (Space Launch System), Orion, exploration ground systems, our core programs for transportation. But Gateway, EHP (Extravehicular Activity and Human Surface Mobility Program), and HLS (Human Landing System) are all also within our purview. And then any exploration activities that we’re going to do beyond the Moon and eventually on Mars currently fall in our mission directorate. I also have the privilege, though, of running the strategy and architecture office within our mission directorate. That was given to me as soon as I came into this role because to Jim Free’s credit, he really wanted to place a strong emphasis on the strategic part of what we’re doing and the development of an architecture that was integrated not just within the mission directorate, but for the agency. And in doing so, he wanted to put me in charge of that so that he showed the importance of that effort.

Host: How did you react to that when he said he wanted you? Were you excited? Were you like, “oh man, this is a big task?”

Cathy Koerner: I think I was caught off guard initially because of that, just that I knew how big a task it really was.

Host: It’s huge. Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: It really is huge, because it’s not just for the mission directorate, it’s for the entire agency. And when you do something like that for the entire agency, you’re really doing it for more than just NASA. You’re doing it also for all of the international partners that participate with us in exploration. You’re really leading that effort. So it was a bit daunting, but I also knew I had tremendous support from leadership.

Host: And your career, you spent, really, your entire career. Is that right? You’ve spent your entire career at NASA?

Cathy Koerner: Not exactly. I did, actually, I worked for a contractor briefly as an intern before I came to NASA. And when I worked at JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) before I came to the Johnson Space Center, I actually wasn’t a NASA employee, I was a Caltech employee at JPL.

Host: Oh, OK. But the contractor that you worked for was part of spaceflight, right?

Cathy Koerner: It was. Yes. Yes.

Host: OK. So you’ve always had your fingers in here and you, so, but when you did transition to NASA, you were flight director. You had roles in ISS and shuttle program, you talked about Orion, Human Health and Performance, if you think about…

Cathy Koerner: And space station. Yeah.

Host: Oh, did I miss that? OK. Space…

Cathy Koerner: If you said it earlier, I missed it, but yeah.

Host: The idea is, you know, if you think about a person who can really try to capture as much of human spaceflight as possible, do you feel like all these roles that you’ve had throughout the years have prepared you to take on, really this effort that is trying to make the big picture, trying to make all these different pieces pull together. Do you think everything you’ve done up to this point has prepared you for that role?

Cathy Koerner: It has, because when I worked at JPL, I did a lot of the lunar Mars formulation kinds of robotic activities. So I’ve done that early in my career. I’ve done operations from the standpoint of humans in low-Earth orbit, and I’ve done assembly, like development activities when we are assembling the International Space Station. So I’ve done like, a broad spectrum of from development, concept development to actual hardware development, to operating a spacecraft. I’ve done that whole spectrum of human exploration and robotic exploration. And that really gives me a different perspective, I think, than some folks may otherwise have.

Host: OK. I think it’s very well appreciated. So, you know, daunting task, right? We kind of went over that. There’s, you have to pull all of these pieces together. When you tackled this, when you started pulling all your teams together to say, “OK, how are we going to define the mission architecture of this endeavor of Moon to Mars?” What were your first steps to gather the team, rally the troops, and take a first step?

Cathy Koerner: So there’s actually been a team of folks that have been working on architectures for a long time within the agency. If you go back and look, historically over time, there have been a number of reports that have been put out. This team has functioned almost, more like a skunk works in the past where they have done the work for Headquarters. And by that, I mean, at the time, the head of HEO (Human Exploration and Operations), or even in some cases, the administrator himself would say, “I want to know if we go do X, what would that look like?” And they would create that architecture and they would do a lot of trades and analysis around whatever X was. So that team has existed for a long time. It’s actually a broad cross agency team.

But they have never done that out in the open. And so, one of the things that we were tasked with doing when I came in, we- meaning Jim and I- when we came into ESDMD, was to really create a process to do this for the entire agency and to let everyone take a look at what’s being done, agree that this is the right architecture for exploration, and then get buy-in across the board. So when we started on this process, when I said earlier, it was a pretty daunting task, it really is because we really wanted to do it not just for an individual concept or idea that someone had, but we wanted to create a process that would outlive not only us, but the current leadership and the current administration. Something that could really be sustained, because that’s what it’s going to take to have an exploration program that is sustained across decades.

Host: And that’s really the meat that I want to get into when we talk about these documents, is that’s really at the core of it. When I see this kind of architecture, you’re thinking about — these documents identify the challenges that we’ve had in the past with making something sustainable. And so, this architecture that you’re talking about, this integrated architecture that goes agency-wide, is really learning from that, battling that, and trying to make something that can be sustained. And then I think what also is that it grows on itself from the human landing all the way to the sustainable presence all the way to, you know, those first steps on Mars. You guys are trying to make like a Goliath. Something that is like, really tough to beat.

Cathy Koerner: We’re really trying to do is create a blueprint for exploration beyond Earth. So exploration to any destination in the future, if we do this right, we should be able to say, “we want to go explore this moon of this planet, or this other planet” and actually have a process to get there, as opposed to what we’ve done in the past. We create a capability. And then, it’s the, “if you build it, they will come” kind of mentality.

Host: Ah. Field of Dreams.

Cathy Koerner: Right? When you build a rocket, you build a spacecraft that can carry humans. And now you go find out what the mission is that you’re trying to do. If you start with that end goal in mind, where you want to figure out how can I make exploration, pick whatever your destination, but make exploration a process, and you back up from there and make sure that you’re talking to all of your stakeholders, you understand why they want you to explore, you understand the why’s or the what’s behind what you’re trying to achieve, then you can actually build an architecture that fulfills that and you can create that sustained lasting exploration activity.

Host: I think one thing that sticks out, you know, when– we’re going to dive into the architecture here in a second, but really what attracted me to be able to pull you in to talk with you today is that everything we’re going to be talking about here is public. These massive plans that go deeper and deeper. And even this, the recent document that really pulled me in this said, whoa, you guys go really deep. And you not only define like, the architecture, but you define milestones and steps within each, like, subcategory. You’ve really thought this through. Like what milestone defines success? And I wonder what, you know, you put all this together, but why share it? Why take all these different things and share it with the world?

Cathy Koerner: So, I have to give credit to our Deputy Administrator, Pam Melroy, who had the vision to say, “we want to do something that is very visible and very public that our stakeholders can buy into, and our international partners can buy into as well.” And so, she brought in “Spuds” Vogel, Kurt Vogel, he goes by “Spuds,” as the agency chief architect to help really look at this process and how to create the end-to-end process, not just the architecture, which I’m responsible for, but like, let’s analyze why are we doing this? What are the, what he calls the three pillars of why we want to explore, and can we make sure that we are always speaking to all of our stakeholders? Which if you hit on all of the why’s behind exploration, you will always be scratching the itch, so to speak, of your stakeholders. Regardless of whether your stakeholders are only interested in science or only interested in making sure that the U.S. has, you know, dominance in economic fields or in prominence in any particular industry. If you’re doing everything right and are anchored to those why’s, then you can make sure that you always have those stakeholders supporting the activities that you’re doing. So Spuds likes to talk about architecting from the right. And so, if you could see me gesturing, you’d see my right hand up because that’s the “why” behind exploration. And from there, you can determine “what.” What do you want to accomplish? What objectives are you trying to accomplish? We wrote a document, a strategy and objectives document that the federated board, which is a cross-agency board led by Spuds Vogel, that we created this document that basically with the help of NASA employees and industry partners and international partners to say, “here are some of the objectives that if you’re going to explore the Moon and then Mars, here are the objectives you’ll need to accomplish.” And we can tie that back to the why’s. And those objectives are meant to be very generic, but also stand the test of time. It’s really hard to argue with them if you look at them.

Host: Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: They’re very high level, but they give you an anchor point to be able to then point back to with the different aspects of the architecture to say, I can meet these objectives with this one architectural element. So that’s a really valuable element to me. I really should be investing in that. And again, it provides that continuity so that our stakeholders see that what we’re doing is really achieving what their end game is. We can tie everything to what their end game is.

Host: I love this as a segue to go ahead and dive in, starting with those why’s, right? Like what is it exactly, when you’re trying to sell this to all these stakeholders, you talked about this “architecting from the right,” just defining the why’s. When I see the why’s in the document, it lists three major ones.

Cathy Koerner: Yep.

Host: And then you can trim them down from there. Science, inspiration, and national posture. So how would you break that down as the, when you say why, and you list those three things, how would you break that down?

Cathy Koerner: Yeah. So if you think about it from a, a stakeholder standpoint, there are lots of people who would say the reason you explore is to go discover new scientific things. Well, that’s like the pure science behind it. But there’s also the applied science aspect, right? We go explore because we want to figure out what has happened, for example, to the climate on Mars so that we understand what’s happening to our climate back here on Earth. Are there’re things that we can do from a science perspective that have that applied science aspect to it? You also have national posture. You want to be the first to discover something, right? You want to be the first to create something. You want to be the first to create an industry and have that energy behind what you’re doing that is broader than just, hey, we’re doing this for purely science reasons. Because if it’s just for purely science reasons, you’re going to hit a very narrow, I’ll say, part of society, right?

Host: Oh, yeah.

Cathy Koerner: Right. But if you have, if you broaden science to be not just science, but science with an application, and then you look at the national posture aspect of that, and you look at, hey, we can create entire industries, which is what, by the way, we’re doing with Artemis. We’re standing up entire industries from large aerospace corporations to mom-and-pop shops across the country and really across the world because we have international partners who are also contributing. You can create that other why, right? And the people who want to be, “make sure America’s first and America is the, you know, is the best.” Well, we can show how what we’re doing is driving our technology and making things better for the U.S. but also for the world and for all of humanity.

You know, and then there’s of course, inspiration, which is, if you’re like me and have been around long enough to remember astronauts walking on the Moon, that was very inspiring and inspired an entire generation of students to study in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields. And also, I mean today, it inspires people just when an astronaut shows them someplace or goes somewhere, when you see a rover on the surface of Mars collecting samples or a helicopter flying off the surface of another planet that’s very inspirational to people. And so, if you can tie all of those together, those why’s and the activities that you’re doing, and point back to those directly mapped back to those, you can tell any one of your stakeholders who might be interested in one of those, how you’re fulfilling what their interests are.

Host: And, really what you’re saying is, if you take those three, the sweep is incredibly broad. I mean, inspiration alone can be a worldwide application, right?

Cathy Koerner: It is. It is.

Host: As you’re saying, you were inspired by people walking on the Moon. You can only imagine Artemis III, people walking on the Moon. Yes.

Cathy Koerner: Even better: Artemis III, a woman walking on the Moon.

Host: A woman walking on the Moon! Yeah. I mean, this is wide, wide applications.

Cathy Koerner: Yeah.

Host: This, you can seriously inspire the world with a mission. Now to dive into the weeds, we keep talking about architecture, we keep talking about architecting from the right, we’re talking about the why. But when we’re talking about architecture, how do you define it? What does that mean?

Cathy Koerner: Yeah. So different people have different ways of saying it, but I would characterize it as a set of functional capabilities that working together really enable missions which can accomplish your scientific and exploration objectives. To say it in one sentence, that’s what it would be. And you can have different levels of architecture too, right? When I look at an architecture, I could talk about the communications architecture, which is all of the communication systems, those capabilities that enable us to be able to communicate while executing a mission. It could also be what we call in our architecture, the human lunar return segment of the architecture, which is all of the transportation systems and habitation systems to take our astronauts from the Earth to the Moon and return them back safely. So there are different levels of architecture, but in a very broad sense, it’s really that collection of capabilities that enable us to accomplish missions and objectives.

Host: Yeah. It captures that why that we just talked about, but in a way, it captures, you know, all the different steps to get you to that…

Cathy Koerner: The architecture is really the how.

Host: Oh, really?

Cathy Koerner: So if you have the why, right? Which is, as we said, science and national posture and inspiration, you can take the why, and then you can create a set of objectives. OK. In order to meet that why, here are the things that I want to do. That’s like the what I want to accomplish. The how you accomplish the what, like that, how is the architecture.

Host: Got it. OK. And within these documents, you actually go through and define how, what, why. You also do when, where, who, right? And you even talked about who, right? When you talked about the stakeholders, we talked about the national posture, but also, you mentioned, bringing together industry, the corporations, the mom-and-pop shops. You talked about the international, I mean, it goes back to that broad suite. But even within the document, you’re actually identifying the who that you want to reach out to.

Cathy Koerner: It is, we’re not only identifying the who we want to reach out to, but the who we want to have involved. Right? Not necessarily just the stakeholders, but who’s going to be part of the party? We have said with the Artemis Accords that any country that wants to explore and abide by these certain principles that we believe are the way you should conduct yourselves in exploration, then we welcome you to participate, come play along with us, right? Be part of this really cool endeavor. It helps, I think it helps us unify humanity as a whole. You know, it brings the world together on something that’s peaceful as opposed to maybe, other ways the world sometimes is forced to come together.

Host: Yeah. That’s one of the things we always stress with the International Space Station too, is just, you know, that we are all, you have countries represented from all over the world on a single place, all in sort of a way, doing the same thing, doing science, doing exploration, same goals. We can all unify. It’s a wonderful, like you can contain this idea of international and the world in a single space.

Cathy Koerner: It is. And you hit on the key questions. You know, the who, what, where, why, when? All of those, you have to satisfy an answer in order to create an architecture. You can’t just do one of them. And if you place any, I’ll say, strong emphasis on one of them, it can completely change your architecture. The example I’ll give you is the Moon by 2024. We had that mandate from a previous administration that came down. You will put someone– well, when you do that, when you put a “when” on your architecture, that drives all of the other decisions. Because if I say, I have to have it by a certain date, now I have to look at, well, what technologies currently exist? Do I have time to develop the optimal technology, or do I have to use a technology that exists today and make it work? So it changes the how you explore and the how you create your architecture. When you pick any one of those questions, instead of trying to optimize around all of them.

Host: It’s refreshing to hear like your mindset and the how, right? And how you tackle that goal of the 2024, because one of the things I read in these documents are the lessons learned from previous attempts to try to create a Moon to Mars and exploration beyond the solar system kind of presence. One of the terms that stuck out to me was this idea of capabilities driven, which is part of the core of these current efforts. That’s what you just said is exactly that, is capabilities. OK. Moon 2024, what do we have? What do we need to get there?

Cathy Koerner: Yeah. If you focus just on capabilities instead of on objectives and make it a capabilities-based, then you look at what do I have today? What can I accomplish with what I have today? If you do it based on objectives, then that shifts your mindset to, hey, what capabilities do I need in order to accomplish those objectives? Not what capabilities do I have? It’s kind of the difference between “if you build it, they will come” as opposed to, “here’s what we want to do, now, let’s build something that will help us do that.”

Host: OK. And so how does that framework change as the timeline goes on, because one of the things that’s within the architecture, and you alluded to one in particular, one that you said, it was human lunar return. That was one of the segments. And that’s those capabilities we need to actually land on the lunar surface again. But it goes on there. You got the foundational exploration, sustained lunar evolution. It goes on to Mars. How do we fold in this capabilities mindset, you know, thinking what we have, but then also what we need. And then defining that as we think about how this evolution of our exploration presence evolves?

Cathy Koerner: So a capabilities framework would have you build things very serially and click off, I’ll say objectives, very serially. Whereas an objective approach would say, you have to do things, some things in a certain order, but if for some reason an element of your architecture is delayed because of, oh, I don’t know, development challenges, a hurricane takes out a launch site or any number of factors. Now you can more easily shift your architecture to reflect, hey, I can still accomplish some objectives, just not necessarily with the same capabilities. I can do other things. And it helps, again, it helps keep your stakeholders engaged and sold on the idea of what you’re trying to accomplish without saying, “hey, you weren’t able to do this mission this time, so therefore you’re clearly not making progress.” Right? It gives you that opportunity to basically shut down the naysayers and show progress towards your ultimate goal when you’re more objective space. Now, you mentioned the different segments of our architecture today. Human lunar return is obviously the first serially because it has to be because it has those core capabilities for transportation and habitation. But then beyond that, the segments will overlap. There is a natural flow to them where we go from the human lunar return to the foundational exploration that adds some additional transportation capabilities. It adds Gateway into the picture and allows us to have access to more places on the lunar surface. But that segment of the architecture can overlap with sustained lunar evolution. As you’re developing sub-architectures and additional capabilities, these tend to overlap. And then with the last segment, the humans to Mars segment of our architecture, we can start that and have actually already started that here at the Johnson Space Center with a terrestrial analog. We can start doing activities that contribute to that without it being that very serial, almost like a mission sequence-focused architecture approach.

Host: Right. You don’t need to get through the first couple before you even start the Mars infrastructure. It’s all related.

Cathy Koerner: It’s all related, right? But you can tie it to these loose groupings of things that contribute to those bigger objectives that I mentioned earlier. Than what you’re trying to accomplish.

Host: OK. Now we’re talking a lot about objectives. And I know part of the architecture is actually defining what trickles down from those key objectives are, you know, the capabilities, the technologies, you’re getting into this is where you…

Cathy Koerner: Characteristics and needs.

Host: Yes, yes.

Cathy Koerner: Use cases and, and elements…

Host: You have a lot of terms in these documents.

Cathy Koerner: We do. Well because people used the terms very, I’ll say, loosely in the past, and so, we tried, part of the reason we document is we tried really hard to make sure that we were all speaking a common language. People have different ideas of a use case, and the utility of a use case. They have different ideas on what constitutes an element. And so, if we can use a common language and get all of us talking, and by all of us, I mean all of our partners; industry as well as international, all talking the same language and using the same terminology, it really helps facilitate our achieving those objectives through the architecture.

Host: Now, of course, Artemis is very much, you know, we’re in it. We have the industry partners; we have the international-

Cathy Koerner: We do.

Host: So, do you see with the architectures that you’ve laid out, and these terms that you’ve defined, do you see that unison, everybody’s kind of speaking the same thing?

Cathy Koerner: It’s converging to that.

Host: It is. OK.

Cathy Koerner: So yeah. So this, this effort that I told you that was kicked off, gosh, over almost two years ago now, to create the why’s and the what’s, the objectives, the strategy, and the objectives for the agency. That’s really architecting from the right. But we have elements of our architecture already in existence, SLS and Orion. Ground system. Those already exist. So if we were to develop those and execute those, that’s executing from the left. So at some point you have to meet in the middle. You have to take what capabilities you have and the goals and objectives that you’re trying to accomplish. And you have to merge them together and thread them together into one architecture.

So there’s a lot of folks, when we had our first architecture concept review back in an earlier part of this year, who said, “well, I guess I’m on the left then because I see what we have today and what we have to do to take those next steps.” And you need that. You need people who are executing from the left, but you also need a plan from the right that ties them together. And so, we’re still in the process. It’s a very iterative process. We’re still in the process of merging those together and fleshing out the entirety of the architecture. What you saw in our architecture definition document is just the first iteration.

Host: I see. Now, another thing is, you talk about focusing on the left for a little bit and all these capabilities. One thing to get to, if you’re thinking from the right too, you have kind of everything molds together in the why? But one of the things that’s interesting is the capabilities we have. You mentioned a couple. You have SLS, Orion, exploration ground systems. You got the logistics, HLS, the spacesuits, and everything. One of the things that kind of jumps out to me as, “ooh, we’ve got to watch out for that” are stove pipes and making sure that not all programs are working in isolation, that they’re on board. So what is the approach now to make sure that, you know, everybody’s sold on the why’s and everybody’s working towards them? And these individual capabilities are all on board for getting us to that unified goal?

Cathy Koerner: So one of the, the things that we’re doing as part of this process is making sure that the architecture process that I tried to describe earlier marries with the program and project development process that everyone’s very familiar with across the agency. There are key milestones that any program and project has to move through in its life cycle. And so, as they move through those milestones, we are making sure that the activities, the functions that we have allocated to those elements, to those programs and projects are maintained. And when they’re not, we have to adjust the architecture by adding something else that can pick up those functions, for example. Or if they’re able to do more, that means we don’t have to create a new element or a new capability because that existing capability can be used to meet that characteristic or that function within the architecture. So it really becomes a, I’ll say the iterative process where we look at the architecture and on an iterative basis. But as we’re hitting the milestones on the production of these programs and projects that those are tied back to the architecture that has been established. So it really, it’s a meeting in the middle. If you could see me gesturing my hands, I’m gesturing my hands, fingers meeting in the middle.

Host: Yeah. We should have done a visual podcast just so can get all the hand gestures.

Cathy Koerner: There you go, so you can see… you have the left and the right and the merging in the middle.

Host: [Laughing] Because it’s helping me to get it. But yeah. So, yeah, we talked about all the elements. We’re talking about the different capabilities. I think, I want to take a step back and go kind of through history. We touched on this just a bit, but one of the things was this idea of how NASA used to be. We had things like the space exploration initiative. We had vision for space exploration. The idea of trying to set goals for the future is not necessarily a new thing. Like…

Cathy Koerner: It’s not.

Host: It’s always been a part of NASA. So really…

Cathy Koerner: John F. Kennedy said, “we will land,” right? I mean…

Host: And we did, right.

Cathy Koerner: And we did. And, but he put a “when” out there. Back to what we said before about the questions, who, what, where, why, when? He put a goal out there and he focused on the “when.” And so, when they accomplished that, they were done.

Host: Right.

Cathy Koerner: That the difference between, if you just focus on one of those, which is what we’ve done a lot in the past, as opposed to, hey, we have all these objectives we’re trying to accomplish. Some of them may never get fully accomplished but we’re still going to be challenging ourselves to do more in a particular area.

Host: Right? Yeah, the idea, yeah. Like Apollo was absolutely incredible, right? But I think what you’re getting at is the idea that there was supposed to be an Apollo 18, a 19. And the idea that what we’re trying to build right now is that continuation. So when you think about…

Cathy Koerner: The sustained exploration activity.

Host: That’s just it. So at the core of it, if you learn from the lessons of the past and you talked about like setting the goal, what really excites you about the difference of this strategy? What makes you feel confident in what we’re doing today?

Cathy Koerner: So what, what gets me excited about it is that I see that it has lasting potential. And by that, I mean it’s independent of a destination. I mean, right now our focus is on the Moon, but that’s to learn to go do the next thing, whatever that next thing is. It has the potential to really go beyond this administration, the next administration. It has staying power. We’re deliberately opening our hands and showing our work and getting buy-in across industries and across international partners so that we have stakeholders across the world. It’s really difficult to cancel something that has that many stakeholders. If you think about if you lived through the Constellation cancellation, right? That was really hard. That was really hard on the psyche of the agency as well as the individuals who really pour themselves into that activity. Well, if we create something that is bulletproof, which I believe this is, then whether we are doing a lot of exploration or a small amount of exploration, we’re still making progress and we still have a vision, we still have a plan. And that’s what this strategy enables us to have. So that regardless of which party is in power, regardless of the circumstances that are surrounding our budget, regardless of the personalities involved, we have something that we can continue to make progress on.

Host: And I think the idea is, there was a lot of thought in exactly what you’re saying, poured into this strategy, because you mentioned Constellation, right? And of course, Orion and SLS have their roots in Constellation, which are folded into this current plan. But what some of the criticisms of Constellation was, it was very much dependent on budget. And so, what you’re saying is this new framework, you’ve thought about that. You’ve thought, OK, how can we evolve from what Constellation was and make it, as you’re saying bulletproof, and the idea that it can resist the politics, you say, it changes from administration to administration. It can be flexible to budget fluctuations. The idea is you have, and this is all captured in this documentation, is this resistance. This idea of a bulletproof plan that gives you that sense of confidence and excitement that you’re selling.

Cathy Koerner: And it’s very adaptable. It’s adaptable so that we can adjust to the changing budget climate. It can adjust and adapt to changes in technology and development. It can adjust and adapt to new entrants into our partnerships, new countries. Some of the fledgling countries that really are just now starting to get involved in space exploration. As they mature and develop, they can come alongside us and participate. So it has that flexibility. This process enables that flexibility.

Host: I’m getting supercharged by this conversation right now. So I’m going to veer off from what I have written and just kind of dive into all these questions that I have. On the whole strategy, I want to pull back and just talk about, you know, why Moon to Mars and why we’re doing what we’re doing? And I’ll actually start with the who? When you think about going to the Moon and Mars, NASA strategically, is welcoming with open arms industry and as you’re saying, international partners, we choose to go together. And so, I wonder, you know, it might be part of this bulletproof strategy, but of all the different ways we could have attempted to have this exploration of the Moon and Mars and beyond, and this kind of framework, why do we choose to bring these folks along? Why do we choose to involve industry and international partners?

Cathy Koerner: I would actually turn that around on you and say, why would we not? We’re not doing this just for ourselves. We’re doing this for all of humanity, right? This is not just an American thing. It’s not just a NASA thing. This is a human thing. Exploration is, I feel like a human thing. It’s in our nature to always want to look beyond the next horizon to explore and to see what’s next out there to push the limits and push the boundaries. So why would we not include anyone who wants to, I’ll say, play nicely with us, right?

Host: Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: As we do that, like somebody who wants to share data and share information, because it makes all of us better. If you look back at all of the innovations, the technologies, the things that have made life better across the globe in the last 50 years, many of those can be tied to the technology investments that were made in the early Apollo days. And continued to be made throughout shuttle and then the International Space Station. The breakthroughs that we’re making in science and technology have ties back to that. And they’re not things that we hold to ourselves. They’re things we share with the rest of the world. And we should because when we lift up one area, we lift up the whole world.

Host: And on a practical note, is this idea is not necessarily novel. This idea of bringing everybody together and doing things together. We have practice on the International Space Station.

Cathy Koerner: We do.

Host: Space station’s original concept was the Space Station Freedom, Space Station Alpha. Some of those early concepts were this national approach. But we brought in international partners, made an international space station. And through the evolution of time and through the space station’s history, now look at us. We have commercial partners, commercial cargo vendors, commercial crew vendors. And this evolution, you know, if you look back and say, why are we going? In a way, to you, is it proven on the International Space Station that, you know, it has developed — naturally or maybe through a lot of effort over time to get us to this point on the International Space Station. And that model can translate easily to exploration.

Cathy Koerner: It absolutely is the model. It is the model. It’s the model for NASA doing something new and unique and then slowly handing off things to industry to develop an entire industry and again, to supercharge the economy in the process of doing that. If you think about it, SpaceX really didn’t exist until we had the commercial resupply services contract on ISS, right? That’s what helped propel them as a company to be more than just an occasional, you know, dilly-dallying with rockets, right, kind of company. And then we help them through the commercial transportation contracts. We help them develop the capability to transport people, which they’re now doing, right? We are enabling that low-Earth orbit economy. I envision the same kind of thing eventually happening in the cislunar environment where NASA goes and we set up the infrastructure and we create the capability there, and then we slowly start handing things off. Because in doing that and handing things off to commercial industry and developing a cislunar economy, we can then say, “OK, NASA, we’re going to back out because we want to go to Mars next.” Right? And we can take the next step to Mars and then the next step after that. So it actually, again, I used the term earlier, it becomes a blueprint for how we do exploration where NASA is the one leading the way, doing the really hard upfront kind of work, and then industry can step in behind us and take over and do the things that industry is best at doing, which is optimizing for productions and services.

Host: Yeah. And it’s not just a concept, it’s not just an idea. I think Commercial Crew is the perfect example for that.

Cathy Koerner: And by the way, this is not novel to space that we do– this is exactly how the United States created the railway system. It’s the way the United States created the airline industry, right? Now, we’re creating the low-Earth orbit economy.

Host: Yeah, yeah.

Cathy Koerner: Right? And eventually the cislunar economy and so forth. So it is really, it’s a similar kind of activity isn’t it.

Host: It’s already embedded into the plans we have for the human lunar return, right? The human landing system, the spacesuits, they’re all with that idea.

Cathy Koerner: All services, right?

Host: All services. Exactly.

Cathy Koerner: All the services there, because we want those economies to develop so that tourism or mining or whatever industry sees as value-added for them where they can make money, again, generating more economic engine for the cislunar environment, whatever they see that as, we’re helping facilitate that.

Host: This idea of Moon to Mars. I kind of wanted to tackle that for just a second, you know, if we think about our exploration goals, and going out into the solar system, that goal has evolved over time. I remember there was a time where we were considering going to an asteroid. We were not going to go to the Moon, that we were going to have a direct approach right to Mars. But over time, the idea has evolved into what it is now, Moon to Mars. And, you know, we’re talking about the capabilities and stuff, but to pull it up to a high-level, why is the Moon a good place to catapult us further into the solar system?

Cathy Koerner: So the analogy I like to use is, if I tell you that you’re going to go on a trip to Humble, Texas, you can probably figure out, yeah, you got to put some gas in your car. Eh, you probably might want to take a snack just in case you get stuck on the freeway, right? If I tell you you’re going to do a trip from here to Alaska, you might have to do a little bit more planning. Especially if you’re going to drive, right?

Host: Oh yeah.

Cathy Koerner: That’s a long drive.

Host: [Laughter] If I’m going to drive for sure.

Cathy Koerner: If you’re going to drive straight through, that’s a few days. Maybe even a little bit longer, but you know, you might be able to get to Anchorage, but you can probably envision what it would take. You might have to make a few more stops, but I’ve said, no, no, no, you’re not going to stop. You’re going to actually have to take all your supplies with you. You might have to actually spend a little bit more time planning and figuring out what you have to take with you, right? And you might have to figure out what time of year you go because the weather on some of those roads might not be the best.

Host: Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: Right? Now, what if I tell you, you, I actually want you to take a trip and you’re going to drive around the Earth. We’ll just say for simplicity’s sake, ten times, it’s farther than that, but I’ll say ten times. And again, you got to take everything with you…

Host: All my gas, all my gas…

Cathy Koerner:…and you’re going to drive…

Host:…no rest stops.

Cathy Koerner:…I’m going to let you, when you get to a port, because you’re going to have to go over water, I’m going to let you prearrange for a water transportation, but yeah.

Host: Thank you.

Cathy Koerner: But you have to actually take it all with you and figure out everything out that you might need. Very different trips, right?

Host: Very different.

Cathy Koerner: Very different. So what we do today in low-Earth orbit is like going to Humble in a way, right? Going to the Moon, it’s like going to Alaska. It’s still pretty darn hard to do that and to make those plans. When we go to Mars, it’s like going around the Earth several times.

Host: Right?

Cathy Koerner: Right? It’s very different. It’s a very different level of planning. There’s a different level of risk associated with it. There’s a different amount of reliability on your transportation systems and tracking for every aspect of the mission. So going to the Moon helps us figure out some of those operations and some of those logistics.

Host: Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: It helps us develop the reliability in our systems so that we know when we do a mission to the Moon, it’s three days maybe depending on the trajectory, you know, three to five days you could probably be back to Earth. When you go to Mars, once you start going, it’s going to be years before you come back, because you got to get there and come back. There’s not a short-abort turnaround. That’s not how the physics of orbit’s work, right? Today, aboard the space station, we have an emergency, you can be on the ground within hours. So it’s just a different magnitude of a challenge. So when we say we need to go to the Moon to figure out how to go to Mars, it’s really to figure out how to go anywhere else.

Host: Yeah. I’m thinking about that Alaska trip, right? So if we take the Moon as kind of like taking several Alaska trips. You’ve did it once. OK. I think I have a good idea how it works. Then you increase your capabilities, you get a better RV, you know, more storage tanks. Next thing you know, you’re taking this trip and you have most of the things pretty farmed out that you kind of know the expectations. And a lot of those technologies you built onto your nice fancy Texas to Alaska RV that can really help you when you are ready to take that around the world ten times.

Cathy Koerner: Yeah. And again, if you think about it from the standpoint of just the learning that is required, we’ve learned so much since the first missions to the International Space Station on how to live and work in space. And the maximum duration that we’ve had with a crew on orbit is a year. When we go to Mars, that’s a round trip of two or more years, if you think about it. Anywhere from, depending on the trajectory, from nine to twelve months out plus whatever time you’re going to spend on the surface. And then nine to twelve months back again depending on this trajectory.

Host: A lot of risk. And you can buy down that risk maybe by testing a lot of those things out on the Moon?

Cathy Koerner: Absolutely. And yeah, we don’t really know, and I have to give the shout out to my Human Health Performance guys, right? We don’t really know how the human system is going to perform in a microgravity followed by a partial gravity back to a microgravity kind of in an environment. We don’t know how the body is going to change. We know today that the human body changes on orbit. Your physiology shifts and changes and adapts and it adapts back once you return to Earth. For the most part. We don’t know what’s going to happen when we get beyond the experience-base that we have in low-Earth orbit.

Host: Yeah. I think the first Artemis lunar landings would be very telling for that exact aspect. I’ve thought about that recently is just the way that the near rectilinear halo orbit works is it kind of circles around to that same point, every, I think, six days or something like that? So if you do a surface operation, you got to make sure you’re rock solid for six days. But on that altered gravity field conversation, you’re going from 1 g, you’re going from the Earth’s gravity to get to the Moon, you got to go into microgravity. Now, you’ve experienced partial gravity for six days only to go back to microgravity and then on the trip home to one gravity. Yeah. That can probably do some things to your body. So if we do that a couple of times, we can maybe have a better understanding for that Mars experience landing on Mars and adjusting.

Cathy Koerner: Or, if you do like we’re talking about for some of the use cases that we have for the humans to Mars part of our lunar exploration strategy, do we go to Gateway, for example, for six to nine months? Simulating the transit to Mars then spend 30 days on the surface in partial gravity living and working and then turn around and spend six to nine months in microgravity. Now, you’ve tested it when, if something happens during that year-plus long simulated Mars mission, but in the lunar environment, you’re only, again, days away from Earth as opposed to months or even over a year away from…

Host: Wow. Wow. It’s, yeah. I haven’t, you’re ahead to, I guess, sustained lunar revolution or maybe one of the later plans. But that idea of doing, for the duration of a Mars mission.

Cathy Koerner: Using the cislunar environment and the assets that we have deployed there to not just do lunar science, but also do some of the precursor operational activities that you would want to burn down risk for a Mars mission.

Host: Wow. Testing your systems, making sure Gateway can support humans. Thinking about that radiation factor, thinking about the engineering factor, the food systems…

Cathy Koerner: The reliability.

Host: All with that…

Cathy Koerner: All these systems. Yeah.

Host:…three-day, three whatever day, maybe six-day depend, I guess it depends on…

Cathy Koerner: Depending on where you are in that profile, but yeah.

Host: But in just a couple of days you can be home in the event of an emergency versus, you’re stuck for years or whatever.

Cathy Koerner: Yes.

Host: Wow. That is a huge, huge win for lunar exploration.

Cathy Koerner: Absolutely. And by the way, when you’re on the surface for 30 days or whatever length of time that we decide is the right test bed for that, you’re doing amazing science for the sake of science, right? You’re actually not just testing out the exploration type systems, but you can be exploring the lunar surface. You can be making discoveries; you can be drilling core samples. You, there’s a lot of neat lunar science that can be accomplished during that length of time.

Host: This Artemis, this architecture has a lot of science built into it. The lunar sciences is incredible. Planetary heliophysics, human and biological, which we just talked about; physical, we talked about applied, you brought it out to applied. There’s a lot that you can…

Cathy Koerner: There is, we are including science objectives and science activities in the early planning stages on purpose, because we want to make sure, I mean, science is the primary reason that we’re going. We want to make sure that we’re accomplishing scientific objectives as we’re doing human exploration.

Host: For that scientific community that is really looking at the Moon, you know, focusing on the lunar side of it for a second. We, you know, we’re part of the goals that we see a lot in Artemis is, you know, the who, what, when, where, is where on the Moon and the lunar South Pole, and the interesting science that that has, from a scientific perspective, why is that so interesting?

Cathy Koerner: So I’m going to do my best channeling of some of the scientists that have told us why. Because they really want to do this podcast, get the lunar scientists in here to talk to you about that.

Host: Oh, we will. Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: They would love to have that opportunity, I’m sure. But there are two primary reasons as I understand it, that the South Pole is really important. One is that the South Pole has a better record of the history of bombardment that the universe saw in its formation because of the, I’ll say, solar wind and galactic wind erosion at the equatorial region, which is where we went in Apollo. The, and I hope I get these numbers right, people, I’m sure will check me later, but the rocks that we brought back from Apollo were dated somewhere in the three billion years ago range. At the South Pole, they’re anticipating that the rocks there that can be recovered are four-and-a-half billion. So, you get better insight into the formulation of the Moon and the Earth/Moon system and therefore, you can have a better understanding of who we are and how our planet was formed.

Host: Wow.

Cathy Koerner: So that has advantages. But also, there are parts of the South Pole because of the craters and because of the low sun angle that are permanently shadowed, we call them PSRs; Permanently Shadowed Regions. And it’s believed that within those regions that you have trapped ice and trapped volatiles. Again, with those, scientists can determine what the constituents were of the early formulation of the Earth/Moon system to help better define those models that we have for that system development. Also, if we can find ice, right?

Host: Oh yeah.

Cathy Koerner: We can extract from ice, hydrogen, and oxygen elements for making fuel as well as sustaining life. That gives us an opportunity to potentially produce in an area that’s easier to get it off the surface. The propellants needed to go on a journey to Mars.

Host: These. So I want to build off of that, because I think we’ve– one gap I think is, at least for me, is getting a decent picture of what we talked a lot about human lunar return. We talked about how it builds to Mars. What I’m trying to get a sense of is the later Artemis missions. When we’re in the foundational exploration and sustained lunar evolution, if we can have a picture, or a narrative of what a mission during that phase would look like, how would you sort of describe, like what we can see in a sustained presence?

Cathy Koerner: So, for in foundational exploration, and again, we’re still fleshing out these parts of the architecture…it’s very…

Host: Right, it’s an evolving process.

Cathy Koerner: It is. And so, these are very notional, but the idea is that for foundational exploration, we’ve increased our capability on the surface to have longer surface days and more roaming capabilities. So it’s when we bring things on like the Lunar Terrain Vehicle, LTV, it’s when the pressurized rover, which is a habitable mobility system arrives on the lunar surface, gives us, again, that extended range and allows us to have, instead of just two people on the surface, up to four people on the surface for a longer period of time. Again, we can get more science done. There are, scientists tell us that there are different regions even within the South Pole, that they want to go sample rocks from because it helps, again, flesh out their models for what they believe to be the evolution of the planets and the evolution of the Moon, as well as our own planet. So they need samples from a variety of locations to make that happen. The other thing about foundational exploration is it brings on the Gateway, which becomes now an aggregation point for us to be able to not only do science in orbit, but also it gives us a launching point so that if we decide, you know what, we need to do a comparative assessment between this part of the South Pole region where we’re exploring, and this other place on a different part of the Moon, Gateway is in a location that we can access all the parts of the lunar surface or nearly all the parts of the lunar surface to do just that. So if a science objective really needs to have a mission to another location, we could go to another location. We could even potentially, if it meets some objectives, go back to one of the Apollo sites with a Human Landing System. That’s a potential. So we’ve again, set up the architecture such that, that the foundational exploration segment gives us that flexibility to meet more objectives. And then as you build onto the next segment, which is the sustained lunar evolution, now you’re developing a larger infrastructure. So things like In-Situ Resource Utilization, ISRU mining capabilities, a long-term surface habitat, that again, gives you an opportunity to do long-term science on the surface. You see that start to take shape in that longer duration. And then you can also have in the sustained lunar evolution segment, you can have, start to see some of those Mars activities show up, right? So again, they overlap. They’re not necessarily serial when we were talking about it. They have a natural evolution, but the objectives for each of the segments can be slightly different and overlapping between how they meet the objectives for exploration.

Host: Looking way far out, right now we’re in sort of a, you talked about like notional and here’s an idea that we have and of course, this is going to build out. But one thing that’s sort of sticking with me is do you see a time where we won’t be using the Moon? Or do you think if we build all of…

Cathy Koerner: Our intent is to go to the Moon to stay.

Host: OK. Yeah. That’s where I was going…

Cathy Koerner: Going to go to the Moon to stay. And again, kind of the analogy I’d like to use is the one that we have for a space station where we create a station, right? And then that helps create, we set up an infrastructure and a capability and we help develop a low-Earth orbit economy, so that then industry can come in and take over doing some of those activities. I see that potential on the lunar surface as well, right? We set up an infrastructure of power and communications and a transportation system that by the way, is a service the way we’ve set it up today, right? With HLS.

Host: Yep.

Cathy Koerner: Now industry can come in and they can create their own habitats. They can create, you think about it, a Marriott on the Moon, right? I mean, spend a short week-long vacation, fly to the Moon, spend a couple days on the surface, come back home, maybe someday that’ll be a possibility, right?

Host: Yeah.

Cathy Koerner: That’s the kind of thing that I see us doing is setting up again for NASA to first to be the primary user and then, eventually NASA to be one of many users of the services and the infrastructure that are on the lunar surface.

Host: When you try to capture the things that we’ve been talking about now, and the architecture and the plans and the future, you have this vision of what that looks like. And you are going out and you’re trying to sell it to not only our partners, the folks that you have to get involved, international partners, commercial partners, different agencies, governments. When you go out to the public and you try to get the public charged on this is really important, how do you sort of frame, how do you capture everything we talked about and frame it into a pitch?

Cathy Koerner: I think it comes back to the why’s that we started with at the beginning. Like, why are you, why are we exploring, why do we do anything? Because really, there’s a lot you can learn. There’s science objectives, but there’s also, it’s important for us to create an economy and to do things that help the economy and spur on national posture. Not just national U.S. posture, but for the other international partners, their national posture and help them meet their objectives as a country, right? And then, anything we can do to inspire young people to put down their phones and their iPads, and focus on STEM education and be part of developing the new technologies that will help humanity across the board, to me, those are easy selling points.

Host: Right?

Cathy Koerner:They’re hard to argue with. They’re easy selling points.

Host: I think that’s the best way you can say, it’s just hard to argue with. It’s so… It’s bulletproof.

Cathy Koerner: That’s the goal.

Host: Well, Cathy Koerner, this has been, for me, a supercharging kind of conversation. When you lay everything out and you talk about the plans and you’re excited about the plans and you have confidence in the plans, it’s just, it’s contagious. And so, talking with you has been an absolute pleasure. Thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast and sharing these amazing plans.

Cathy Koerner: Gary, thanks for having me again. It was a lot of fun.

[Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. Wow, what an incredible conversation with Cathy Koerner. There was a lot of energy in this conversation. In fact, afterwards, we got to talking and she had just spoken to the United Nations about all of these plans and was coasting off of that energy. So the timing of us recording this episode was absolutely perfect. I was super energized by this conversation, and I hope you were too. Now you can go to NASA.gov/MoontoMarsArchitecture. There’s actually a full website dedicated to all the documents that we talked about today. And if you really want to, you can do an extremely deep dive into the plans that we have at the agency and how we’re involving international and commercial partners on this incredible endeavor. Again, we’ve talked about Artemis and Mars, the Moon, we’ve talked about it quite a bit on this podcast, and you can check out our full collection at NASA.gov/podcasts. Listen to any of our episodes, in no particular order. We also have many podcasts across the whole agency, and you can check out those podcasts at that website as well. If you want to talk to us or give us a question or a suggestion, we’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. And you can use the hashtag #AskNASA on any one of those platforms to submit an idea for the show or ask a question, just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on June 16th, 2023. Thanks to Will Flato, Daniel Tohill, Justin Herring, Dane Turner, Heidi, Lavelle, Abby Graf, Belinda Pulido, Jaden Jennings, Pat Ryan, Hsia Franklin, and Rachel Kraft. And of course, thanks again to Cathy Koerner for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.