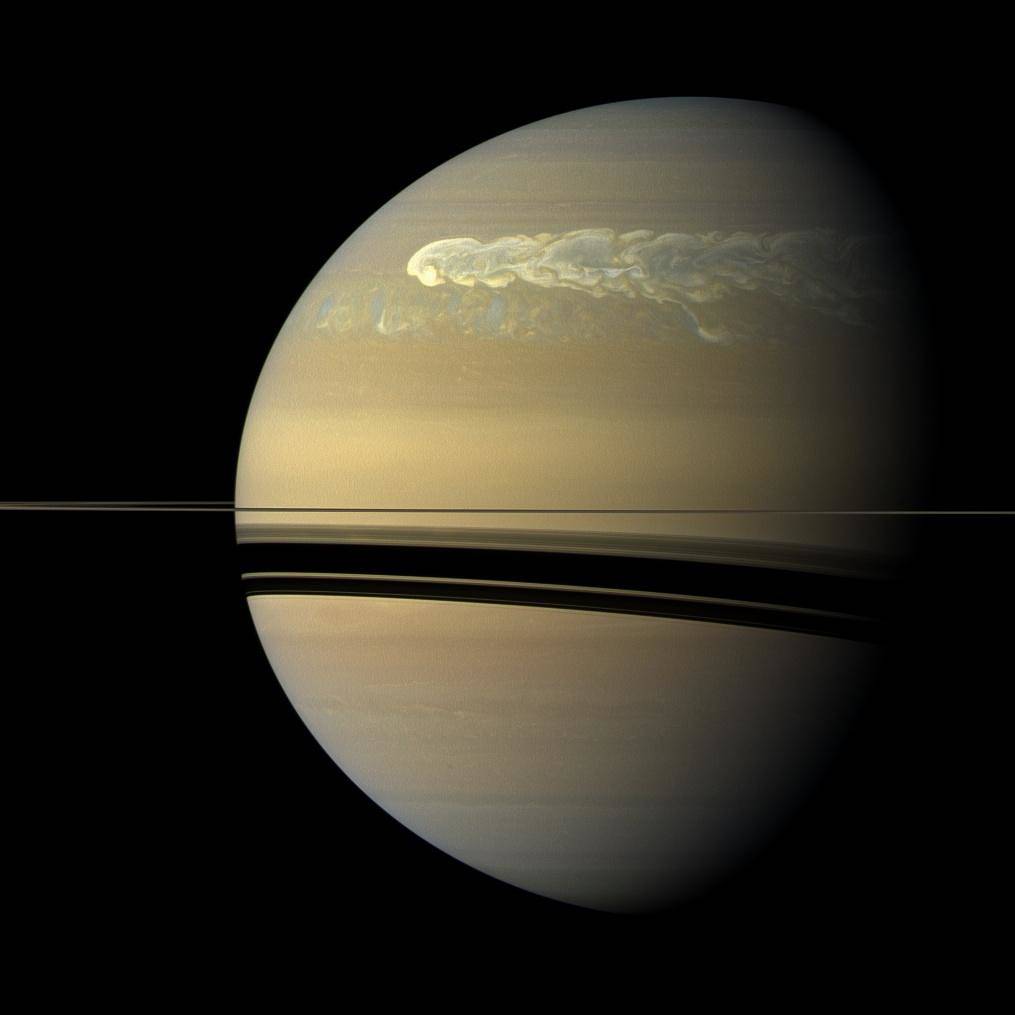

The huge storm churning through the atmosphere in Saturn’s northern hemisphere overtakes itself as it encircles the planet in this true-color view from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft.

This picture, captured on Feb. 25, 2011, was taken about 12 weeks after the storm began, and the clouds by this time had formed a tail that wrapped around the planet. Some of the clouds moved south and got caught up in a current that flows to the east (to the right) relative to the storm head. This tail, which appears as slightly blue clouds south and west (left) of the storm head, can be seen encountering the storm head in this view.

This storm is the largest, most intense storm observed on Saturn by NASA’s Voyager or Cassini spacecraft. It is still active today. As scientists have tracked this storm over several months, they have found it covers 500 times the area of the largest of the southern hemisphere storms observed earlier in the Cassini mission (see PIA06197). The shadow cast by Saturn’s rings has a strong seasonal effect, and it is possible that the switch to powerful storms now being located in the northern hemisphere is related to the change of seasons after the planet’s August 2009 equinox.

See PIA12824 for a nearly true-color view taken in December 2010. See PIA12825 for false-color high-resolution views of the storm taken in February 2011.

Huge storms called Great White Spots have been observed in previous Saturnian years (each of which is about 30 Earth years), usually appearing in late northern summer. Saturn is now experiencing early northern spring, so this storm, if it is a Great White Spot, is happening earlier than usual. This storm is about as large as the largest of the Great White Spots, which also encircled the planet but had latitudinal sizes ranging up to 20,000 kilometers (12,000 miles). The Voyager and Cassini spacecraft were not at Saturn for previous Great White Spot appearances.

The storm is a prodigious source of radio noise, which comes from lightning deep in the planet’s atmosphere. The lightning is produced in the water clouds, where falling rain and hail generate electricity. The mystery is why Saturn stores energy for decades and releases it all at once. This behavior is unlike that at Jupiter and Earth, which have numerous storms going on at all times.

This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from just above the ring plane.

Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were acquired with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 80 miles (129 kilometers) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission, visit https://www.nasa.gov/cassini and http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov .

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

3 min read