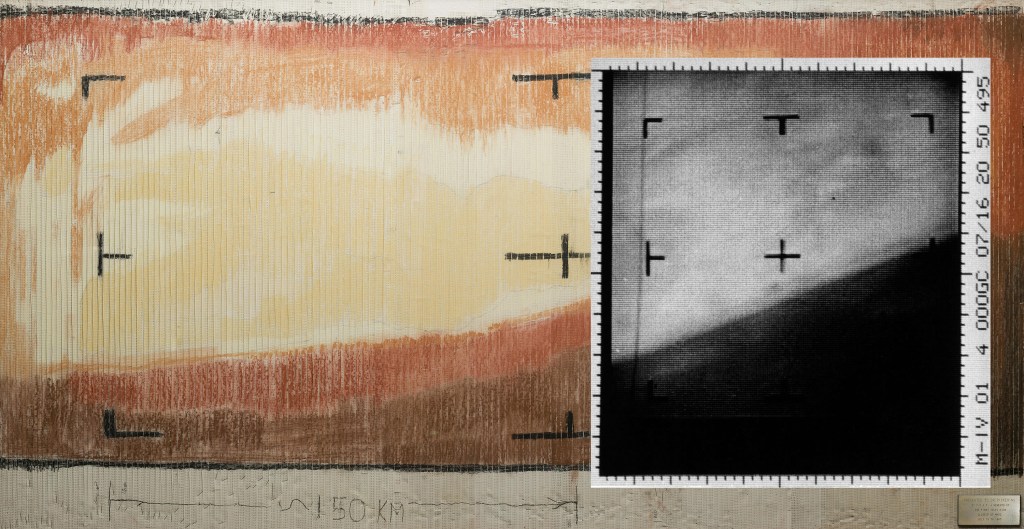

In July 1944 a B-29 Superfortress aircraft conducted a series of flight tests at the NACA’s Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory (now NASA Glenn) in Cleveland, Ohio. The tests were part of a national effort to get the new bomber into combat as the Allies sought to turn the tide in the Pacific theater of World War II.

Boeing designed the Superfortress to make precision bombing strikes from altitudes out of reach of enemy defenses. The revolutionary aircraft could fly higher and farther than previous bombers. The rush to get the aircraft into the war, however, resulted in an array of problems.

One of the primary concerns was the overheating of the aircraft’s four Wright R-3350 engines as they struggled to reach high altitudes with their heavy payloads. The center employed several teams of researchers and test facilities to investigate the R-3350 cooling issue.

What they discovered was that design of the R-3350 piston heads did not allow for enough heat dissipation, resulting in exhaust valve failures. Researchers designed a new elongated cylinder head that had enough surface area to properly disperse the heat.

The R-3350’s carburetor was also not distributing the fuel evenly to each of the engine’s valves, so engineers designed a new impeller to increase the injection flow and create a uniform fuel supply to the cylinders.

During wind tunnel evaluations, researchers discovered there was insufficient cooling in the engine’s exhaust area, so baffles were inserted into the engine to direct the cooling air flow to that area. They also redesigned cowl flaps to increase cooling air without causing further drag.

A B-29 arrived at the laboratory on June 22, 1944 to flight test the NACA findings. Technicians installed the new modifications in the bomber’s two left-wing engines. Test pilots from Wright Field tested it in the Cleveland skies ten times with different combinations of the modifications.

Overall the flight tests corroborated the wind tunnel and test stand studies. With proper fuel mixture and cowl flap settings the engine attained its maximum range on each flight. The baffles and fuel injection impeller increased performance by 38% during periods of maximum cooling. The investigators estimated that this translated into an extra 10,000 feet of altitude or 35,000 pounds of payload.

The Superfortresses overcame their early travails and became a decisive weapon in the final years of World War II. B-29s went on to perform refueling, reconnaissance, and patrol duties in the post-war years.

Top Image: A Boeing B–29 Superfortress parks at the NACA’s laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The aircraft was used in July 1944 to flight test a series of modifications developed by researchers to reduce engine heating.

Robert S. Arrighi

NASA Glenn Research Center