In March 1978, space shuttle Enterprise embarked on its first long-distance journey, from California to Alabama. The Approach and Landing Test (ALT) program conducted in 1977 at NASA’s Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California using Enterprise cleared the space shuttle for flight in the Earth’s atmosphere

In March 1978, space shuttle Enterprise embarked on its first long-distance journey, from California to Alabama. The Approach and Landing Test (ALT) program conducted in 1977 at NASA’s Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California using Enterprise cleared the space shuttle for flight in the Earth’s atmosphere, but much testing remained before the program’s first orbital flight. Carried on the back of a modified Boeing 747 aircraft, Enterprise traveled to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, with a stopover in Houston. Enterprise spent one year at Marshall undergoing vibration tests that saw it mated to an external tank and solid rocket boosters for the first time. After completion of the vibration tests that proved the orbiter’s structural integrity, Enterprise continued its journey, this time to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

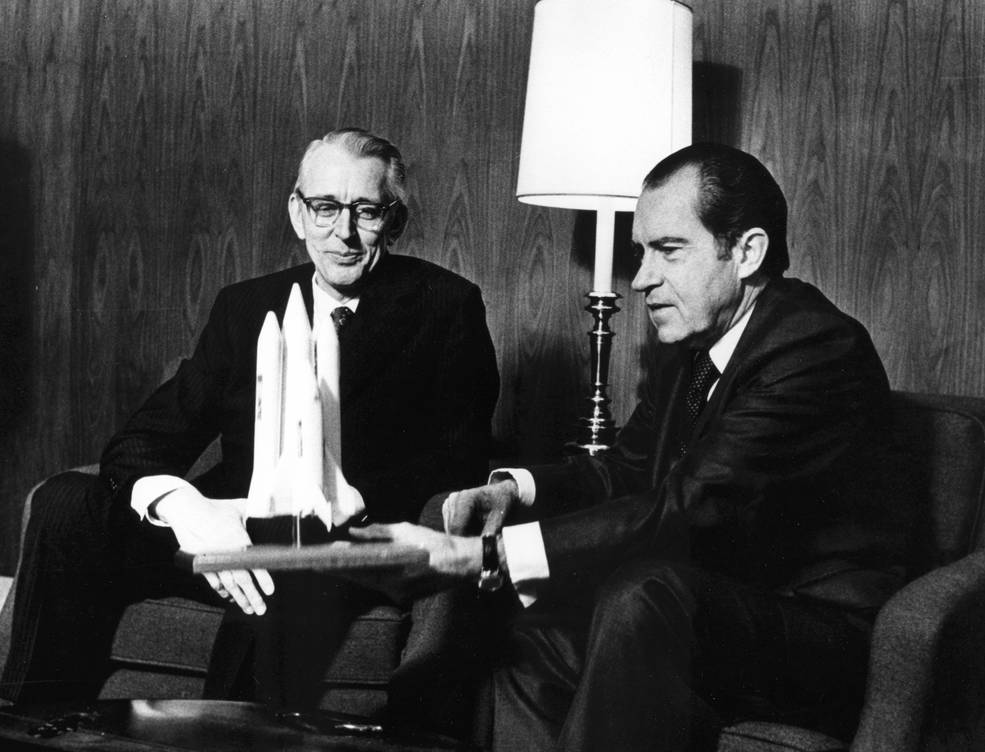

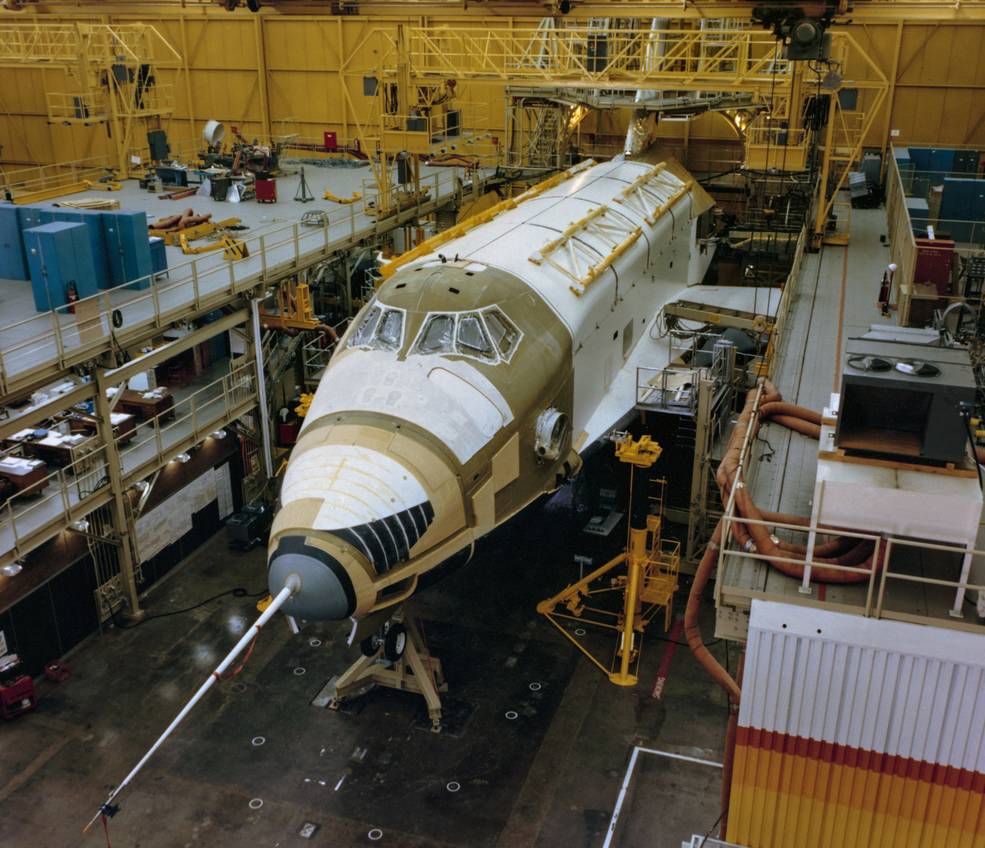

Left: NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher, left, and President Richard M. Nixon present a model of the space shuttle to the press in January 1972. Middle: Space shuttle Enterprise begins to take shape in May 1975 at North American Rockwell’s Palmdale plant, with the fuselage at upper right and the wings at left. Right: Enterprise nearing completion in June 1976.

The story of space shuttle Enterprise began on Jan. 5, 1972, when President Richard M. Nixon directed NASA to build the space shuttle, formally called the Space Transportation System, stating that “it would revolutionize transportation into near space.” NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher hailed the President’s decision as “an historic step in the nation’s space program,” adding that the reusable shuttle would change what humans can accomplish in space. Once Congress authorized the funds, on July 26 NASA awarded the contract to the North American Rockwell Corporation of Downey, California, to begin construction of the first vehicles. Manufacture of the first components of Orbital Vehicle-101 (OV-101) began on June 4, 1974, with assembly of the orbiter completed at Rockwell’s facility in Palmdale, California, on March 12, 1976.

Left: NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher, left, accompanied by several cast members and the creator of the TV series “Star Trek” at Enterprise’s rollout. Right: Astronauts C. Gordon Fullerton, left, Fred W. Haise, Joe H. Engle, and Richard H. Truly pose in front of Enterprise.

NASA originally chose the name Constitution for OV-101, the first space shuttle vehicle designed for use in ground and atmospheric tests. A determined write-in campaign by fans of the science fiction TV series “Star Trek” convinced NASA to rename this first vehicle Enterprise, after the fictional starship the show made famous. That was the name painted on the vehicle’s side when it made its public rollout at Rockwell’s Palmdale facility on Sept. 17, 1976. Several “Star Trek” cast members as well as the show’s creator Gene Roddenberry attended the event to witness the rollout, accompanied by NASA Administrator Fletcher and the four NASA astronauts scheduled to conduct the atmospheric tests with Enterprise – Fred W. Haise, C. Gordon Fullerton, Joe H. Engle, and Richard H. Truly.

Left: Workers tow space shuttle Enterprise through the streets of Lancaster, California, on the way to the Dryden Flight Research Center, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, at Edwards Air Force Base. Middle: Workers tow Enterprise into the Mate-Demate Device in preparation for mounting onto the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA). Right: Space Shuttle Enterprise moments after release from the back of the SCA during the first Approach and Landing Test free flight.

On Jan. 31, 1977, workers towed Enterprise from the Palmdale facility to NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB). The 36-mile overland journey took 10 hours. On Feb. 7 and 8, in the Mate-Demate Device at Dryden, workers lifted Enterprise and placed it on the back of the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), a modified Boeing 747, to begin the ALT program. The duo completed three taxi runs on Feb. 15, followed by five captive inactive flights without a crew aboard Enterprise between Feb. 18 and March 2. Three captive active flights with a crew aboard the shuttle took place in June and July, and Enterprise made its first ALT free flight on Aug. 12, with Haise and Fullerton at the controls. Astronauts completed four additional independent flights by Oct. 26, with Haise and Fullerton alternating with Engle and Truly flying Enterprise. For the last two flights, workers removed the protective tail cone fairing to evaluate the aerodynamic effects from the main engines, in a more accurate simulation of a shuttle returning from space. Following the ALT flights, technicians reinstalled the tail cone and performed maintenance on Enterprise to prepare it for its first cross-country ferry flight. Workers replaced the forward attachment strut on the SCA to lower Enterprise’s cant from six to three degrees for better aerodynamic performance on long-distance ferry flights. Four test flights in mid-November of the Enterprise SCA combination verified the ferry flight configuration. Engineers then prepared Enterprise for its longest journey yet.

Left: Space shuttle Enterprise atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) in the ferry flight configuration on display during an open house at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California in November 1977. Middle: Enterprise during its weekend stop at Ellington AFB near NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Right: The SCA carrying Enterprise prepares to land at the Redstone Arsenal adjacent to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Enterprise began its first cross-country trip on March 10, 1978,with the SCA lifting off from Edwards bound for Marshall. The duo made a weekend stop at Ellington AFB near NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, where officials held an award ceremony to recognize individuals involved in the ALT program. An estimated 250,000 people came out to see Enterprise at Ellington on March 11 and 12. On March 13, it was on to Huntsville, Alabama, where the duo made a landing at the Redstone Arsenal adjacent to Marshall, greeted by an estimated 7,000 people, including Marshall Center Director William R. Lucas. The next day, workers lifted Enterprise from the back of the SCA, and a day later trucked it through Marshall to the Dynamic Test Stand. On March 18, about 85,000 people gathered to view Enterprise and the large white external tank to be used in the upcoming tests.

Left: Visitors gather around space shuttle Enterprise atop its Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) at the Redstone Arsenal airfield adjacent to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Middle: Workers lift Enterprise from the back of the SCA. Right: Workers tow Enterprise through Marshall on its way to the Dynamic Test Stand.

Left: Workers lower the large white External Tank (ET) into the Dynamic Test Stand at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Middle left: Workers prepare to lift space shuttle Enterprise for the first time into the test facility. Middle right: A view from inside the test facility as workers lift Enterprise. Right: Workers lower Enterprise into the test facility to mate it with the ET.

The Mated Vertical Ground Vibration Tests sought to verify that the shuttle in its launch configuration could withstand the stresses of liftoff and ascent as predicted. The dynamic test facility, Marshall’s Building 4550, first built in 1964 to conduct similar tests on Saturn rocket stages and modified to accommodate the winged orbiter, supported the space shuttle test article and provided the vibration input for the tests. For the first round of vibration tests, on April 21, 1978, workers mated Enterprise to only the ET. These tests, conducted between May 30 and July 14, simulated the flight profile from after the separation of the SRBs. By filling the ET with varying amounts of water, engineers simulated points in the ascent including right after SRB separation, midway through the flight to orbit, and just prior to reaching orbit.

Left: Workers lift Enterprise into the Dynamic Test Stand at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, Tank (ET) and inert Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). Middle right: For the first time, a shuttle orbiter joins an ET and a set of SRBs. Right: Workers remove Enterprise from the test stand for the final time at the end of the vibration tests.

For the second series of tests begun on Oct. 20, 1978, the configuration also included a pair of inert SRBs and when engineers mated Enterprise to the ET, marked the first time the three main components of the space shuttle system were assembled, with an overall weight of about four million pounds. Engineers conducted tests in the liftoff configuration with the SRBs filled with inert propellant and with empty SRBs to simulate the period just before SRB burnout, completing the tests on Feb. 28, 1979. The results provided a detailed understanding of the structural dynamic characteristics of the vehicle, giving engineers and managers confidence that the shuttle would withstand the dynamic forces during an actual launch. Following completion of the tests, workers removed Enterprise from the test stand and prepared it for its next objective: the April 10 ferry flight to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida where workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building assembled Enterprise with an ET and two SRBs and rolled the stack out to Launch Pad 39A for compatibility tests in preparation for the first orbital mission using space shuttle Columbia, then planned for later in 1979.