On Sept. 29, 1988, space shuttle Discovery roared off its launch pad at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. The STS-26 mission returned American astronauts to space after a 32-month hiatus following the January 1986 Challenger accident that took the lives of seven astronauts. A Presidential Commission investigating the accident identified proximate hardware and NASA organizational causes. The agency spent two years correcting the problems. Discovery’s five-man crew of Frederick “Rick” H. Hauck, Richard “Dick” O. Covey, John M. “Mike” Lounge, David C. Hilmers, and George D. “Pinky” Nelson completed a four-day mission, deploying their primary payload, a Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, and conducting science and technology experiments. The Return To Flight mission ended with a touchdown at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

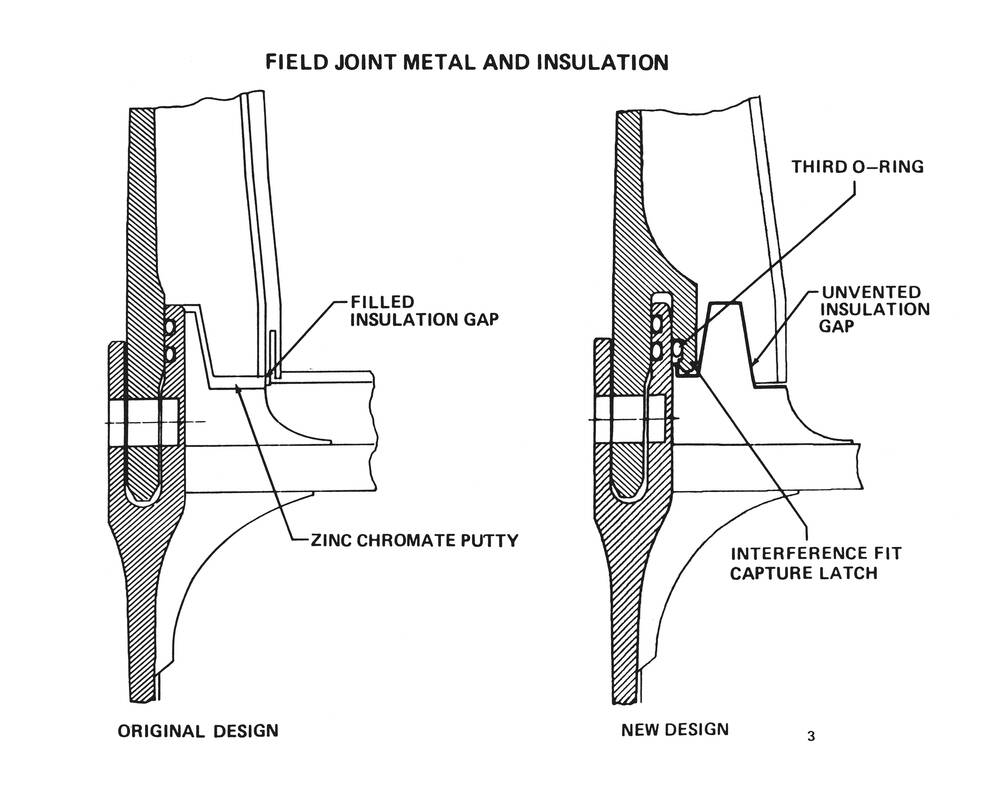

Left: A black puff of smoke (marked by the red circle) coming from the right hand Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) seconds after Challenger’s launch, indicates failure of the O-ring at the field joint. Middle: During their investigation, members of the Rogers Commission examine a SRB field joint. Right: Schematic of the redesign of the SRB field joint.

President Ronald W. Reagan established The Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, also known as the Rogers Commission after its chair, former Secretary of State William P. Rogers, to investigate the causes of the accident and provide recommendations. The commission determined the proximate cause of the accident to be O-rings in the field joints of the Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) that became brittle when exposed to cold temperatures such as on the day of Challenger’s launch. And when the O-rings failed, hot gases escaping from the SRB impinged on the External Tank’s liquid hydrogen tank, causing the fatal explosion. In addition to the hardware failure, the commission also identified cultural and management practices at NASA that led to the ill-fated decision to launch Challenger under those conditions, overriding technical analysis that it was not safe to do so. To recover from the accident, NASA implemented over 200 changes to the Shuttle system, including redesign of the SRB field joints, addition of a crew escape pole to permit bailout from the vehicle under certain flight conditions, and having the crews wear full pressure Launch and Entry Suits (LES) during liftoff and landing. The agency augmented its safety culture and management structure to improve future decision making.

Left: Discovery rolls into the Orbiter Processing Facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to begin modifications and processing for STS-26. Middle: The STS-26 crew following the press conference announcing their assignment to the Return to Flight mission. Right: A qualification test of the redesigned Solid Rocket Booster.

In 1986, NASA decided to use space shuttle Discovery for the return to flight mission. The orbiter had completed six missions, the last one, STS-51I, in August 1985. At the time of the Challenger accident it was in temporary storage in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at KSC. On Oct. 30, 1986, workers towed it from the VAB to the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) to begin work on more than 200 modifications and then processing the vehicle for the return to flight mission, officially designated STS-26 on Nov. 3. On Jan. 9, 1987, NASA announced the STS-26 crew – Commander Hauck, Pilot Covey, and Mission Specialists Lounge, Hilmers, and Nelson – the first since Apollo 11 composed entirely of space veterans. Engineers redesigned the SRB field joint that caused the Challenger accident and in 1987 and 1988 conducted test firings using full-scale SRBs to certify the design.

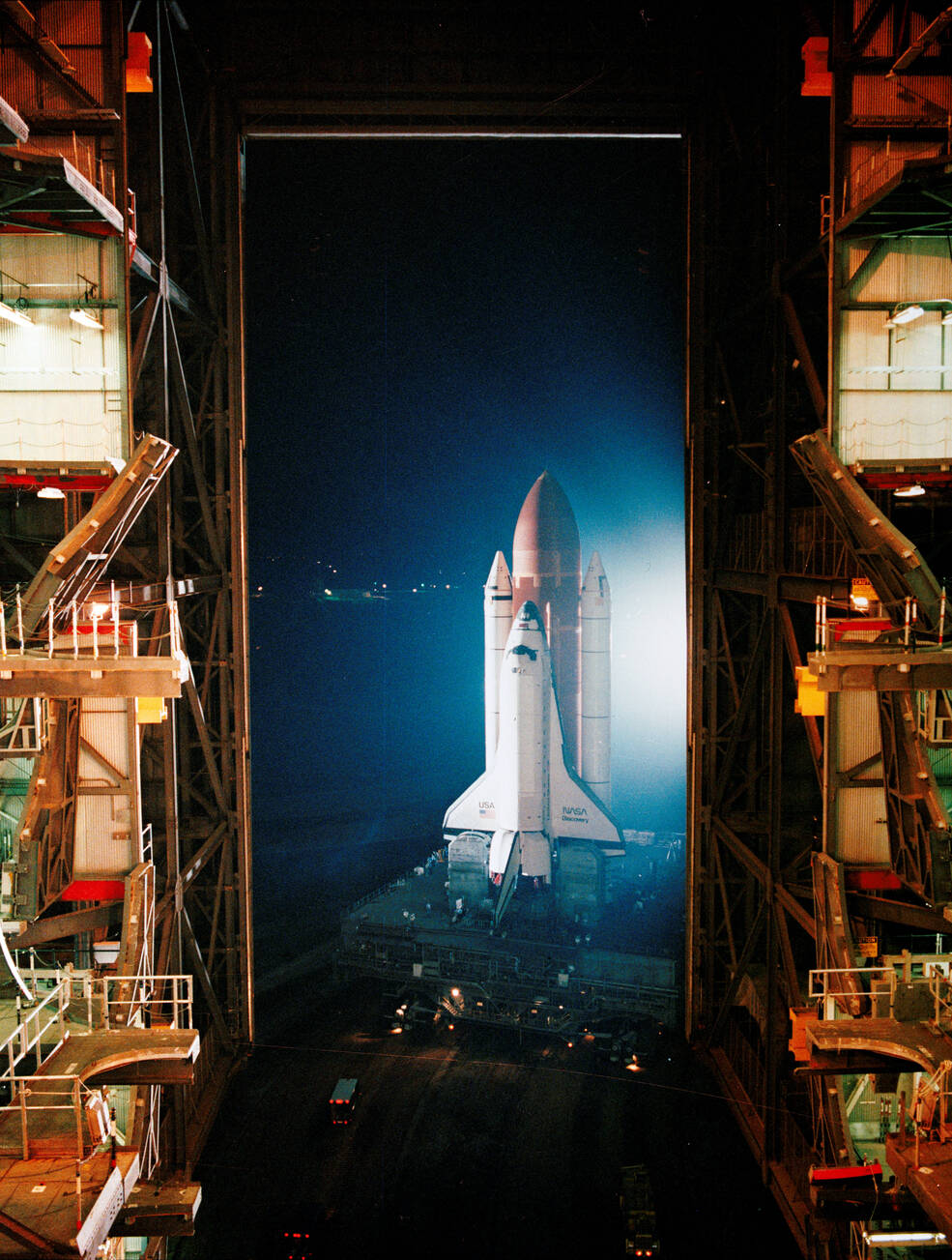

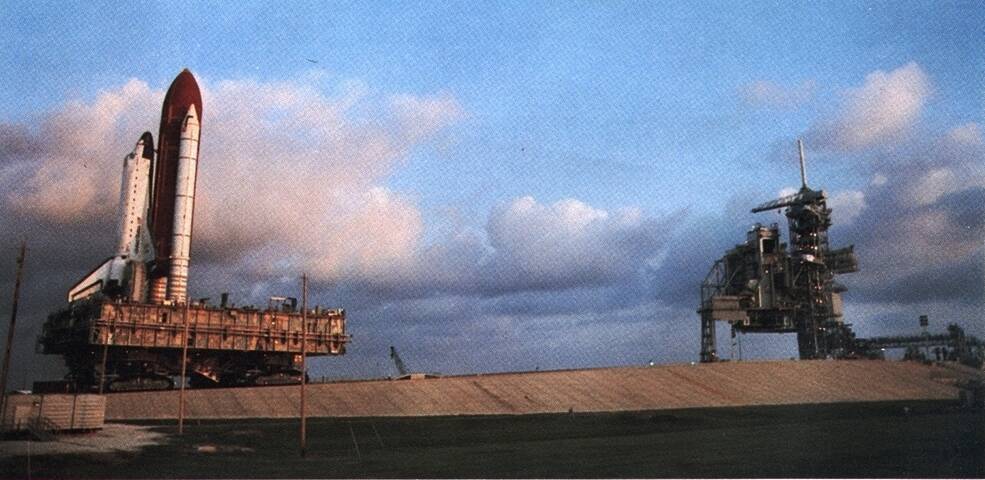

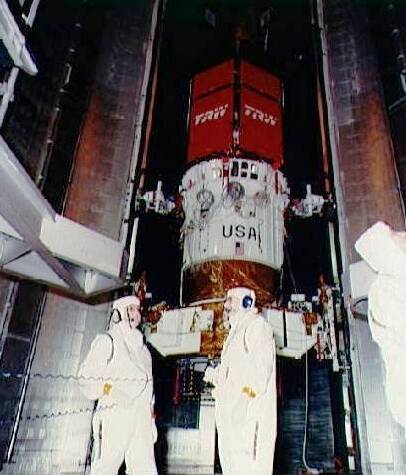

Left: TDRS-3 stacked with its Inertial Upper Stage in the Vertical Processing Facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle left: In KSC’s Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), workers stack the segments of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). Middle right: Workers roll Discovery from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the VAB. Right: After stacking with the SRBs and External Tank, Discovery begins its rollout to Launch Pad 39B.

The primary payload for the mission, the third Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-3), and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), arrived at KSC in May 1988. Astronauts during the STS-6 mission deployed the first TDRS in April 1983, while the second one was lost in the Challenger accident. When completed, the TDRS constellation allowed near continuous communication between the space shuttle, and later the space station, and Mission Control. Meanwhile, in the VAB, workers began stacking the segments of the two redesigned SRBs on March 29, completing the task on May 28. They mated the External Tank (ET) to the SRBs on June 10. After spending 600 days in the OPF, on June 21 Discovery rolled over to the VAB where workers mated it with the SRB and ET. After verifying mechanical and electrical interfaces, on the Fourth of July the stack rolled out of the VAB to make its 4.2-mile journey to Launch Pad 39B.

Discovery rolls out to Launch Pad 39B on the Fourth of July 1988.

Although delayed by several minor hydrogen leaks, a wet countdown demonstration test in which engineers filled the ET with super cold liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen concluded on Aug. 1. The first attempt on Aug. 4 to conduct the Flight Readiness Firing (FRF) was aborted less than a second before ignition of Discovery’s main engines, caused by a faulty valve that engineers replaced at the pad. On Aug. 10, the FRF concluded successfully with a 22-second firing of Discovery’s three main engines. Workers transferred the TDRS-3/IUS to the pad on Aug. 15 and loaded it into Discovery’s payload bay two weeks later. On Aug. 30, controllers in the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston and the STS-26 astronauts in the shuttle simulator completed a 56-hour simulation of their mission. Back at KSC, on Sept. 8 the astronauts participated in the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test, a rehearsal of the actual countdown for launch. Following the Sept. 13-14 Flight Readiness Review, managers set Discovery’s launch date for Sept. 29. The countdown for launch began on Sept. 26. By launch day, more than 1,000,000 people had gathered on nearby beaches to watch the space shuttle take to the skies once again.

Left: Discovery’s three main engines light for the Flight Readiness Firing. Middle: Technicians load the TDRS-3 communications satellite and its Inertial Upper Stage into Discovery’s payload bay. Right: The STS-26 crew arrives at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test.

Left: The STS-26 crew of John M. “Mike” Lounge, left, Richard “Dick” O. Covey, David C. Hilmers, Frederick H. “Rick” Hauck, and George D. “Pinky” Nelson wearing the new Launch and Entry Suits. Middle: The STS-26 crew patch. Right: Launch of STS-26 from Launch Pad 39B.

On Sept. 29, after a one-and-a-half-hour delay caused mainly by unfavorable winds, first Discovery’s three main engines roared to life and as the countdown reached zero, the twin SRBs ignited, and the shuttle rose from its launch pad. The KSC public affairs officer announced, “Lift off! Americans return to space as Discovery clears the tower.” And at that moment, control of the mission shifted from KSC to the Mission Control Center at JSC where a team of controllers led by ascent Flight Director Gary E. Coen, with astronaut John O. “JO” Creighton serving as the capsule communicator (capcom), monitored all aspects of this seventh flight of Discovery. Everyone heaved a sigh of relief at about two minutes into the flight when the redesigned SRBs completed their task and were jettisoned, to be later recovered at sea. The shuttle continued under the power of its three main engines, drawing fuel and oxidizer from the still attached ET. Eight and a half minutes after liftoff, the main engines cut off as planned and the ET was jettisoned. Although Discovery was in space, and the astronauts now weightless, they were not yet in orbit. Forty minutes into the flight, the astronauts fired Discovery’s two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to circularize their orbit at an altitude of 184 miles. Hauck radioed to Mission Control, “It’s nice to be in orbit.”

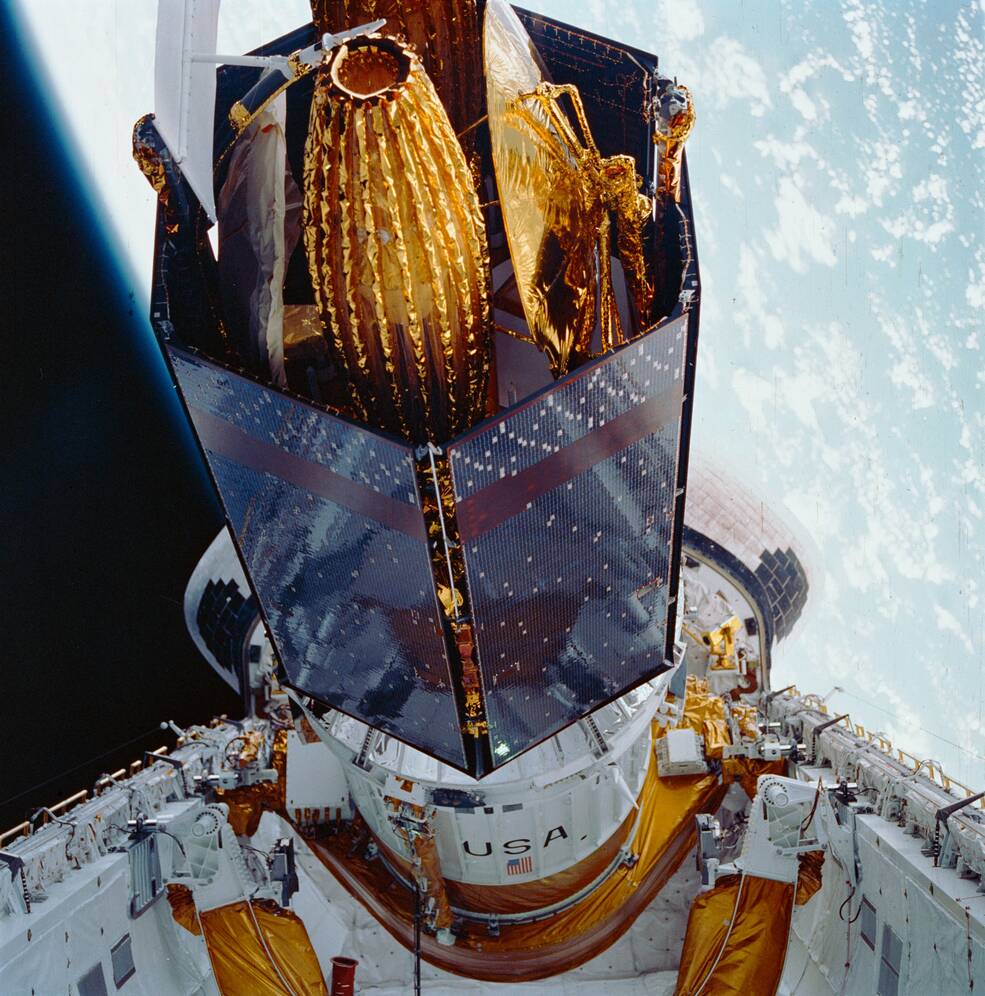

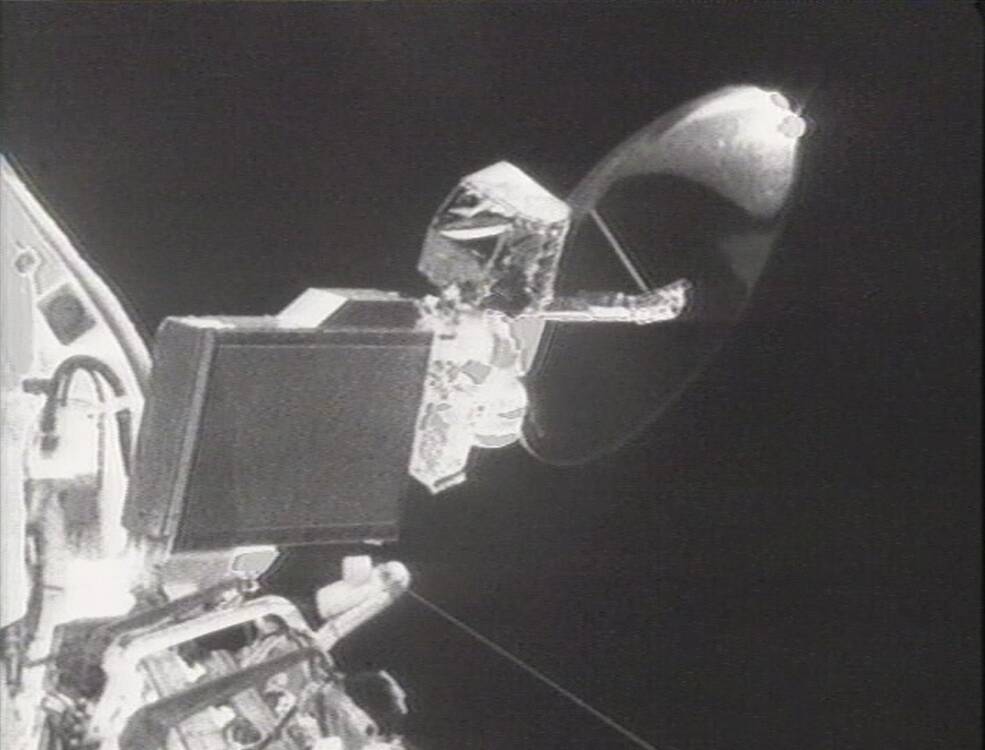

Left: The TDRS/IUS combination in its tilt table raised to its pre-deploy position in Discovery’s payload bay. Middle left: The TDRS/IUS seconds after deployment. Middle right: The TDRS/IUS departs the space shuttle. Right: The empty tilt table in Discovery’s payload bay after deployment.

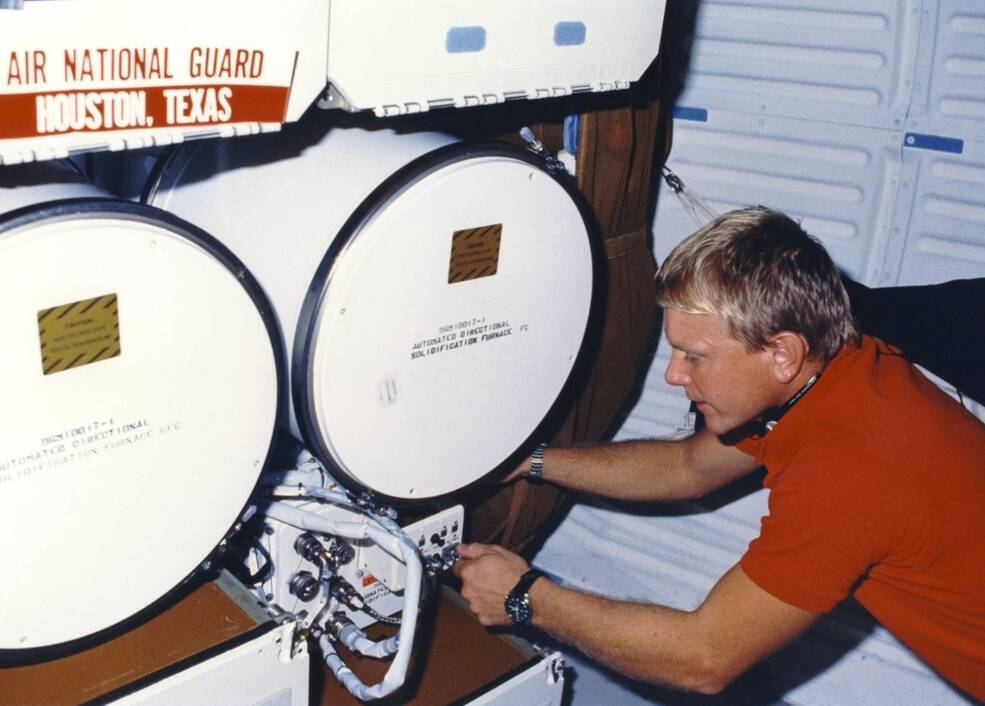

The astronauts’ first order of business involved opening the payload bay doors, that also enabled the large radiators to begin cooling the shuttle. They also received permission to remove their bulky and warm LESs, and begin on orbit operations in a more comfortable shirt-sleeve environment. They then turned their attention to deploying the TDRS and its IUS. They activated the satellite, its upper stage, and the tilt table that they rested in. First they rotated the tilt table up to 29 degrees to continue the checkout, and then to 50 degrees for the deployment. Six hours 13 minutes into the mission, Lounge threw a switch to activate springs that pushed the TDRS/IUS out of its cradle and sent it sailing over the crew compartment. Forty-five minutes later, the first stage of the IUS fired, followed later by the second stage, successfully placing TDRS-3 into geosynchronous orbit. Following a thorough checkout by ground teams, the satellite entered service with its on-orbit counterpart. The crew of STS-26 had delivered their primary payload. Near the end of the crew’s first day in orbit, Nelson began activating some of the secondary payloads in the middeck. Hauck summed up the day for capcom C. Lacy Veach, “We just want to tell you how pleased we are to be up here. We appreciate all the hard work everybody’ done down there. And we’re real proud for NASA, the contractors and the country to be back in space.” The astronauts ate dinner and began their first night’s sleep in space.

Left: Capsule communicator Kathryn D. Sullivan in Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston at the beginning of flight day 2. Middle: The Ku-band antenna in Discovery’s payload bay. Right: STS-26 astronaut George D. “Pinky” Nelson working on a secondary payload in Discovery’s middeck.

To begin their second day in space, the STS-26 astronauts received a most unusual wakeup call. Actor Robin Williams had taped a special message for them. Paraphrasing his famous line from the 1987 film “Good Morning, Vietnam,” he called, “GOOOOOOD Morning Discovery! Rise and shine, boys. Time to start doing that shuttle shuffle.” Mission Control, including capcom Kathryn D. Sullivan, followed this with a special tune, sung to the theme song of the 1960s sitcom “Green Acres,” but with the words changed to “On orbit is the place to be/Free-wheeling on Discovery./Earth rolling by so far below/Just give her the gas and look at that baby go!” Hauck replied, “GOOOOOD Morning Houston! We thank you for that nice wakeup music.” Just prior to an expected television downlink, Mission Control realized that the actual position of the Ku-band antenna in the shuttle’s payload bay, used for communicating with the TDRS satellites, did not match its commanded position. Capcom G. David Low requested that the crew park the antenna. In case the antenna could not be stowed, and the payload bay doors could not be closed for entry, Nelson and Lounge would perform an emergency spacewalk to manually stow the antenna. But the antenna stowed properly, requiring no spacewalk. The astronauts spent the rest of the day working on the secondary payloads.

Left: Lloyd C. Bruce, investigator for the metallurgy student experiment, watches as STS-26 astronaut John M. “Mike” Lounge operates it aboard Discovery. Middle: Frederick “Rick” H. Hauck practices donning his Launch and Entry Suit. Right: A view of the Hawaiian Islands from Discovery.

To begin the astronauts’ third day in space, capcom Pierre J. Thuot had another surprise for them, this time a parody song to the tune of The Beach Boys’ “I Get Around.” The song began, “Round, round, we orbit around/Well we rode her all of Pad 39B/The most sophisticated baby that you ever did see.” During the day, the astronauts spent time working on secondary payloads, including two student experiments – an alloy experiment in metallurgy and a crystallization experiment. In anticipation of landing two days away, they practiced donning their bulky LESs, the first time they attempted the task in weightlessness. At the end of the day, they beamed down television images as they passed over the Hawaiian Islands, home to capcom Veach.

Left: Dressed in red, white, and blue polo shirts, the STS-26 crew poses during the inflight press conference. Right: Dressed more casually, the STS-26 astronauts wear Hawaiian shirts presented to them by workers in the Orbiter Processing Facility at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

The astronauts’ fourth day in space began with another humorous wakeup call, this time the taped voice of Robin Williams poking fun at Nelson’s alma mater, Harvey Mudd College, with a chorus of eight students from the college singing its fight song to the tune of “The Mickey Mouse Club”. The mood turned more somber later when, at the beginning of a televised press conference, the STS-26 astronauts paid tribute to the STS-51L crew who perished in the Challenger accident, a photograph of that crew visible on the wall behind them.

Hilmers began. “We’d like to take a few moments today to share with you some of the sights that we have been so privileged to view over the past several days. As we watch along with you, many emotions well up in our hearts – joy, for America’s return to space – gratitude, for our nation’s support through difficult times – thanksgiving, for the safety of our crew – reverence, for those whose sacrifice made our journey possible.”

Lounge continued. “Gazing outside we can understand why mankind has looked towards the heavens with awe and wonder since the dawn of human existence. We can comprehend why our countrymen have been driven to explore the vast expanse of space. And we are convinced that this is the road to the future – the road that Americans must travel if we are to maintain the dream of our Constitution – to ‘…secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and to our posterity.’”

Covey spoke next. “As we, the crew of Discovery, witness this earthly splendor from America’s spacecraft, less than 200 miles separates us from the remainder of mankind; in a fraction of a second our words reach your ears. But lest we ever forget that these few miles represent a great gulf – that to ascend through this seemingly tranquil sea will always be fraught with danger – let us remember the Challenger crew whose voyage was so tragically short. With them we shared a common purpose; with them we shared a common goal.”

Nelson continued. “At this moment our place in the heavens makes us feel closer to them than ever before. Those on Challenger who had flown before and had seen these sights, they would know the meaning of our thoughts. Those who had gone to view them for the first time, they would know why we have set forth. They were our fellow sojourners; they were our friends.”

Hauck concluded. “Today, up here where the blue sky turns black, we can say at long last, to Dick, Mike, Judy, to Ron and El, and to Christa and to Greg … ‘Dear friends, we have resumed the journey that we promised to continue for you; dear friends, your loss has meant that we could confidently begin anew; dear friends, your spirit and your dream are still alive in our hearts.’”

Capcom Low responded, “And Discovery, on behalf of the Challenger families, and all of us down here, it sure feels good to see the Challenger’s mission continued … and America back in space.” The astronauts spent the remainder of the day preparing for entry and landing the next day, and with a lighthearted television broadcast, wearing Hawaiian shirts and pretend surfing in weightlessness. The team in KSC’s OPF had presented the astronauts with those Hawaiian shirts on Aug. 10, 1987, a week after powering up Discovery for the first time in its preflight processing flow.

Mission Control during the STS-26 crew’s tribute to the astronauts lost in the Challenger accident. Flight Director J. Milton “Milt” Heflin, center, and capsule communicator G. David Low, right.

Mission Control played another playful wakeup call for the astronauts’ last day in space, a customized version of The Beach Boys’ “Fun, Fun, Fun.” After the song, Hauck playfully said, “Life’s a beach,” prompting capcom Sullivan to respond, “Indeed, indeed …” The astronauts donned their LESs and closed the payload bay doors. After capcom L. Blaine Hammond gave them the go-ahead, they fired Discovery’s two OMS engines for 2 minutes 50 seconds to begin their journey back to Earth after completing 64 orbits. With 425,000 people, including Vice President George H.W. Bush and his wife Barbara, assembled to watch, Hauck guided Discovery to a smooth landing on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California. The shuttle rolled to a stop after a mission lasting 4 days, 1 hour, and 1 minute, having traveled 1.68 million miles.

Left: Space shuttle Discovery makes a successful landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California to conclude the STS-26 mission. Middle: The astronauts exit Discovery waving a large American flag. Right: The STS-26 crew poses with Vice President George H.W. Bush.

Mission Control during the immediate postlanding activities.

After reuniting with their wives and a brief welcoming ceremony at Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center at Edwards AFB, the astronauts boarded a plane bound for Ellington AFB in Houston. A large enthusiastic crowd of well-wishers met them there, along with JSC Director Aaron Cohen and Houston Mayor Kathy Whitmire. Discovery returned to KSC on Oct. 8, making the cross-country trip atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing-747, and workers in the OPF began preparing it for its next mission, STS-29. The STS-26 crew held a press conference at JSC on Oct. 11, showing a video of their mission and answering reporters’ questions. The astronauts returned to KSC on Oct. 25 to thank workers there who prepared them for their launch. Like in the old Mercury days, they were treated to a parade down Highway A1A. Following inspection of the recovered SRBs, engineers found them in excellent condition, the redesigned field joints having worked as advertised. America was back in the human spaceflight business.

Left: Space shuttle Discovery takes off from Edwards Air Force Base in California, to begin its cross-country trip to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft. Right: STS-26 astronauts George D. “Pinky” Nelson, left, John M. “Mike” Lounge, David C. Hilmers, Richard “Dick” O. Covey, and Fredrick “Rick” H. Hauck during the postflight press conference at JSC.

Read Rick Hauck’s, Dick Covey’s, Mike Lounge’s, and Pinky Nelson’s recollections of the STS-26 mission in their oral histories with the JSC History Office.